“Maybe you’ve always thought of war as a business for the tough and the unimaginative.

It has been said that the best soldier leaves his emotions at home;

that pre-battle training is a period calculated to harden both mind and body.

But what of the boy who cannot harden?

What of the lad who cannot put his sensitivity in a suitcase and store it for the duration?

Walter Miller tells us.”

– Introduction to “Wolf Pack”, by Walter M. Miller, Jr., Fantastic, September-October, 1953

____________________

If the spirit of an age – its dreams and moods; fancies and wonders; fears and hopes – is reflected in its literature, then a prime example of such remains Walter M. Miller., Jr.’s 1959 novel, A Canticle for Leibowitz. Based on and derived from three short stories published in the mid-1950s – the first of which shares and perhaps inspired the novel’s title – only a decade after the development of atomic weapons and amidst the (first?) Cold War, Miller’s tale was one of many works of science-fiction that presented a vision of the world, and particularly man’s place within that world, subsequent to a global nuclear war.

In this context, I strongly recommend the recent (October, 2020) essay about Miller’s Canticle by Pedro Blas González, “A Canticle for Leibowitz and Cyclical History“. Therein, Dr. Gonzalez discusses Miller’s novel through the lens of Catholicism (to which Miller converted after the war), viewing the novel as an expression of Miller’s interpretation and understanding of the nature of history. As implied (albeit not specifically mentioned) within Dr. González’s essay, and moreso readily understood through a reading of the Canticle, Miller did not view human history as being “progressive” – and thus not having an “arc” in any direction – but instead, as being cyclical, even if those cycles would occupy great intervals of time.

Though doubtless inspired by technological developments and geopolitics of the mid-twentieth century, the two animating ideas of Miller’s novel extend well beyond science fiction, for they represent chords of thought embedded deep within the psyche of men, nations, and civilizations. These are the idea of an apocalypse, and, the gradual and tenuous rebirth of civilization after centuries during which the collective knowledge of the past (perhaps our present?…) has become myth at best, and utterly forgotten at worst. However, rather than concluding upon a note of redemption, the book’s final chapters leave the reader with a sense of deep ambivalence, for the novel suggests that the currents of history are by nature cyclic.

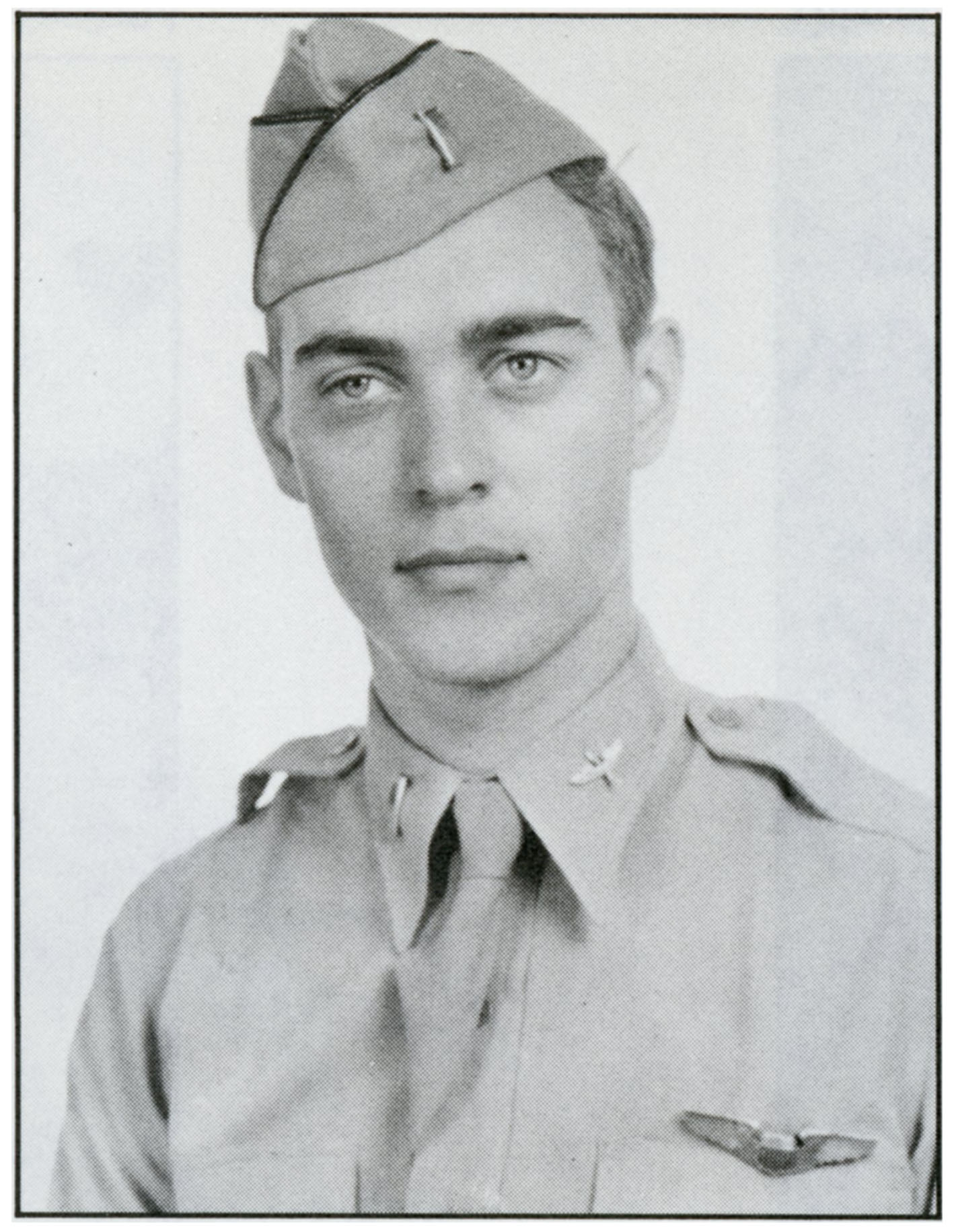

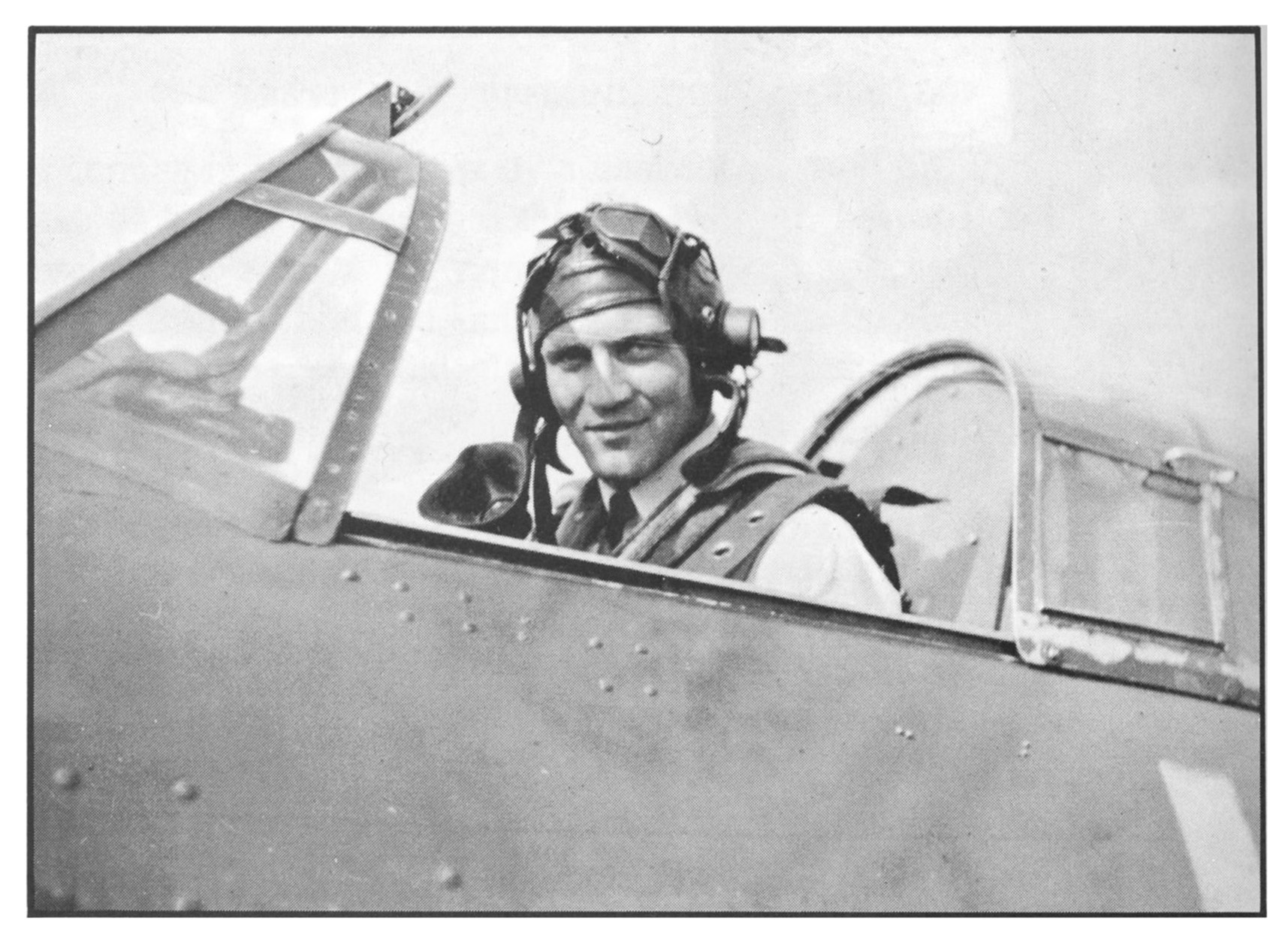

Despite the novel’s origin during the Cold War, Miller’s inspiration for A Canticle for Leibowitz seems to have arisen from something simpler, immediate, and intensely personal: His military service during the Second World War, during which he served as an aerial gunner and radio operator in the United States Army Air Force. Specifically, the impetus for his creation of the stories and novel was his participation in a combat mission during which his bomb group participated in the destruction of the hilltop abbey of Monte Cassino. As discussed in academic and popular literature (see Alexandra H. Olsen’s paper in Extrapolation, William Roberson’s Reference Guide to Miller’s life and fiction, and Denny Bowden’s essay at Volusia History) on a fundamental level Miller world-view was profoundly affected, if not irrevocably altered, by the experience.

Though most sources (at least, web sources) about Miller describe his military service in general terms, Roberson’s Reference Guide specifically identifies Miller’s military unit: The 489th Bombardment Squadron. The 489th was one of the four squadrons of the 340th Bomb Group (its three brother squadrons having been the 486th, 487th, and 488th), a unit of the Mediterranean-based 12th Air Force which flew B-25 Mitchell twin-engine medium bombers. During the time that Miller was a member of the 489th (probably late 1943 through mid-1944) the squadron was stationed at the Italian locales of San Pancrazio, Foggia, Pompeii, and the Gaudo Airfield.

The 489th’s evocative unit insignia, which doubtless adorned the leather flight jackets of many of its officers and men, is shown below…

The best resource on the web (certainly better than anything in print!) for information about the 489th and 340th is the website of the 57th Bomb Wing Association. This resource, covering the 57th’s four bomb groups (the 310th, 319th, 321st, and 340th) gives access to an enormous amount of information, as original Army Air Force Group and Squadron histories and Mission Reports, (many of which are transcribed as PDFs), and, a plethora of photographs. Typical of Army Air Force WW II military records, there’s a degree of variation in the quantity and depth of this information from group to group, and, squadron to squadron: Records for some (most?) combat units are complete, though there are inevitable gaps, “here and there”.

The best resource on the web (certainly better than anything in print!) for information about the 489th and 340th is the website of the 57th Bomb Wing Association. This resource, covering the 57th’s four bomb groups (the 310th, 319th, 321st, and 340th) gives access to an enormous amount of information, as original Army Air Force Group and Squadron histories and Mission Reports, (many of which are transcribed as PDFs), and, a plethora of photographs. Typical of Army Air Force WW II military records, there’s a degree of variation in the quantity and depth of this information from group to group, and, squadron to squadron: Records for some (most?) combat units are complete, though there are inevitable gaps, “here and there”.

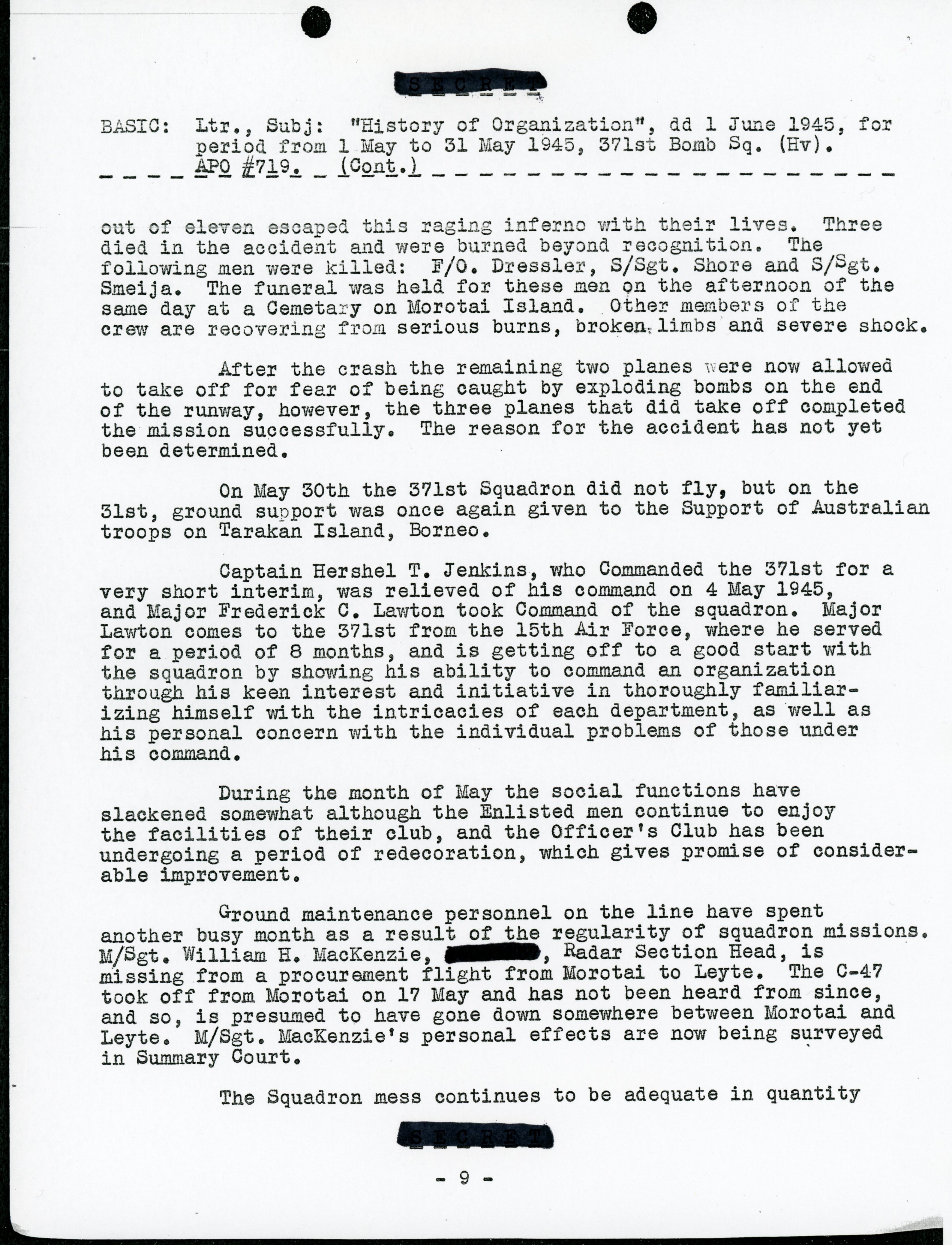

In documents pertaining to the 489th, I’ve discovered three references to Miller’s military service.

____________________

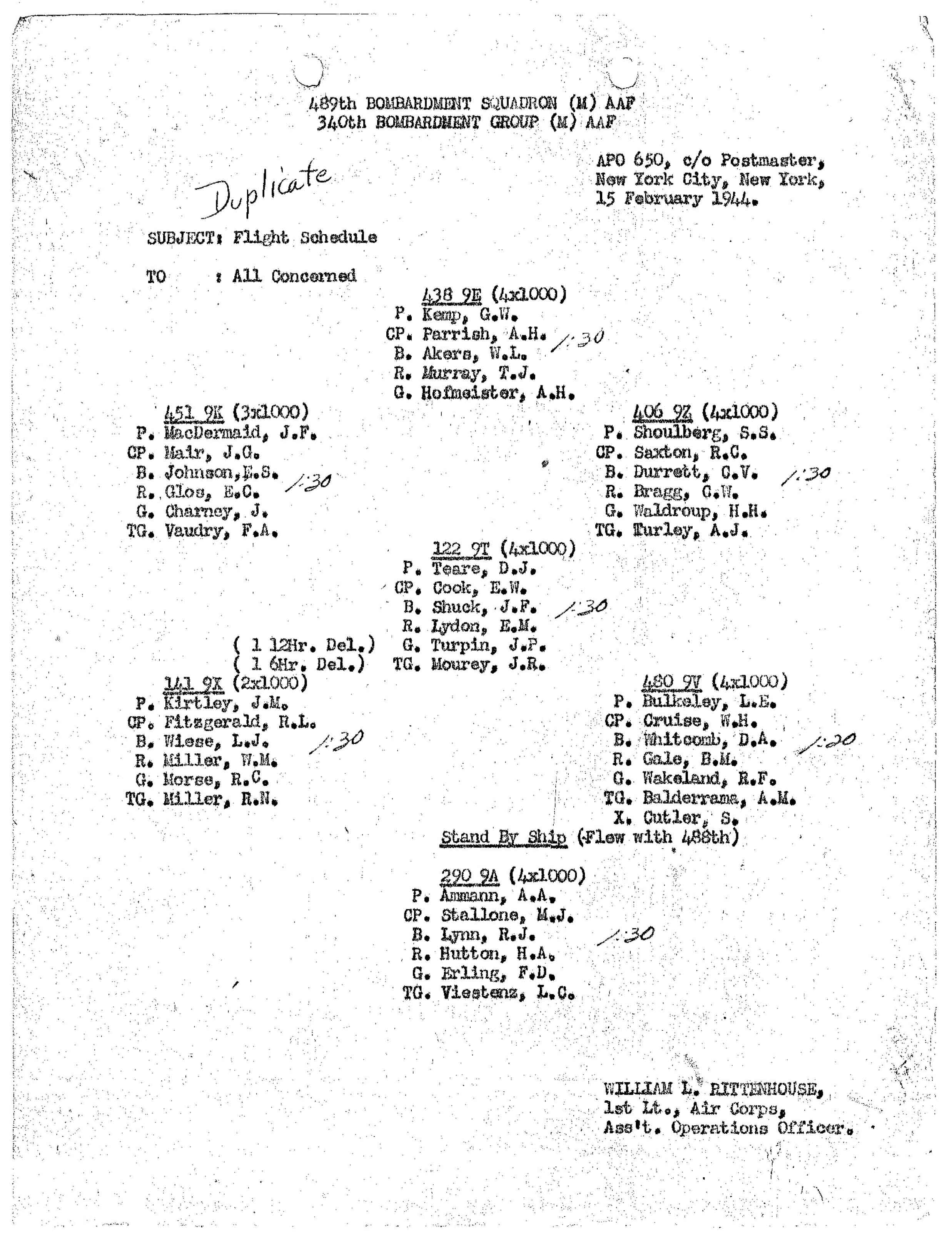

First, Timing: A record of combat missions flown by the 489th during the February of 1944. For the fifteenth of that month, the record – like that for all other missions – is unsurprisingly laconic: “Benedictine Monastery, Italy. 6 planes.”

____________________

____________________

Second, Identification: Miller’s name appears within a list of airmen who, already having received the Air Medal (for completing five combat missions), had been awarded two Bronze Oak Leaf Clusters, thus signifying the completion – by the end of February – of up to fifteen combat missions. His name is listed eleventh from the top in the “upper” list…

____________________

____________________

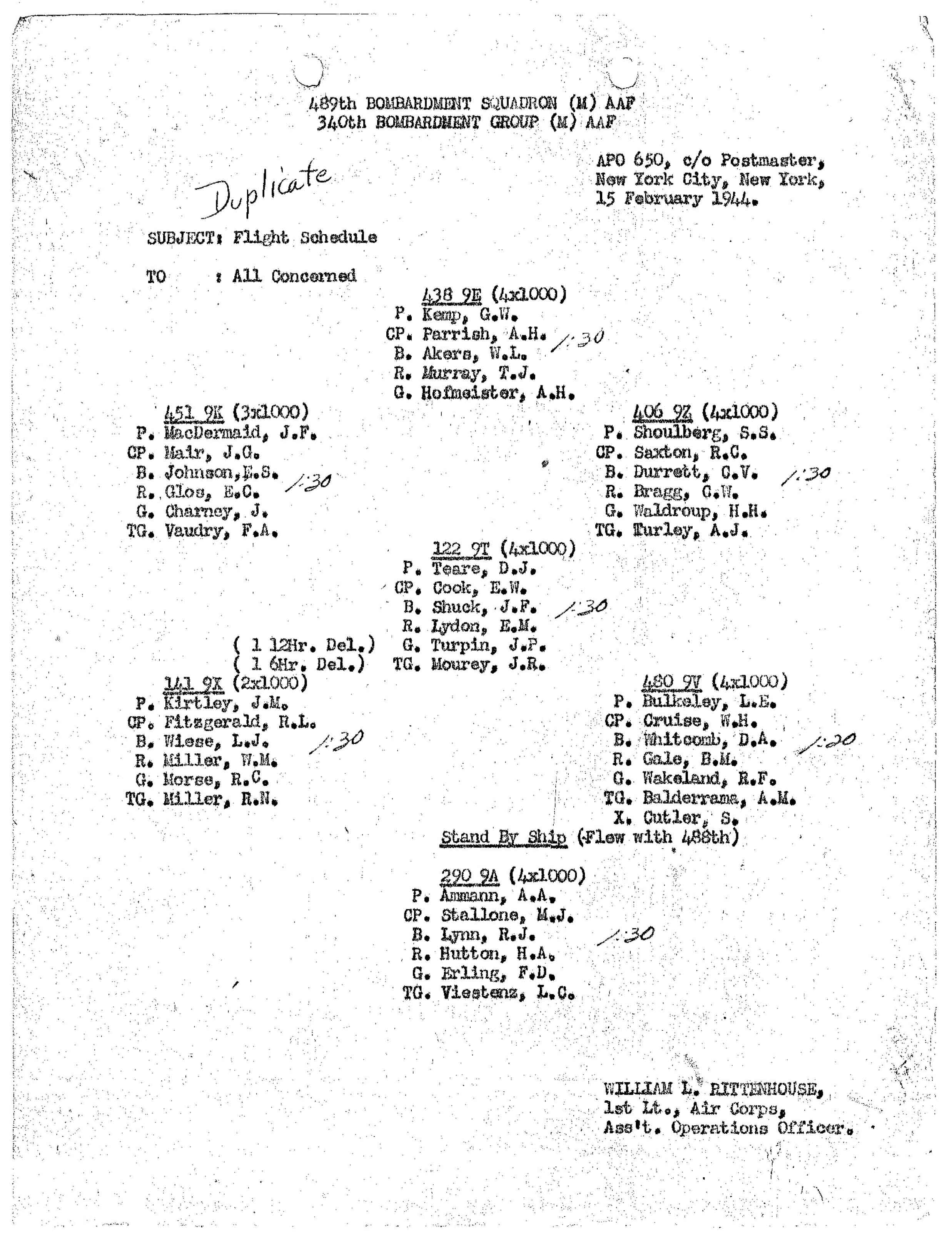

Third, Verification: This “third” document – also found at 57th Bomb Wing – is what’s known in the parlance of the WW II Army Air Force as a “Loading List”, meaning that it lists the names of crewman assigned to specific planes during a combat mission or sortie, on an aircraft-by-aircraft basis. This Loading List, covering 489th Bomb Squadron aircraft and crews which participated on the Cassino mission of February 15, 1944, shows that seven of the Squadron’s B-25s took part in the mission.

Each plane is denoted by a three-digit number, which represents the last three digits of the B-25s Army Air Force serial number. This is followed by the number “9” and a letter, the “9” representing the 489th Bomb Squadron, and the adjacent letter – a different letter for every plane in the squadron – uniquely identifying each B-25 in the squadron. Each such number-letter combination was painted on the outer surface of the twin vertical tails of the squadron’s planes, a practice shared by the 340th’s other three squadrons. This is followed by information about the planes’ bomb loads, which – in all cases but one – were three or four thousand-pound demolition bombs.

Then, we come to the crews themselves, which follow the same general sequence: P (Pilot), CP (Co-Pilot), B (Bombardier), R (Radio Operator), G (Aerial Gunner / Flight Engineer), and TG (Tail Gunner).

Where was Walter M. Miller, Jr.? He’s there: He was a radio operator in the aircraft commanded by J.M. Kirtley, B-25 “#141”, or, “9X”.

As the 57th Bomb Wing includes Loading Lists for other missions flown by the 489th (and the 340th Bomb Group’s three brother squadrons), doubtless Miller’s name appears in these documents, as well. But, this will suffice for now.

As the 57th Bomb Wing includes Loading Lists for other missions flown by the 489th (and the 340th Bomb Group’s three brother squadrons), doubtless Miller’s name appears in these documents, as well. But, this will suffice for now.

____________________

The image below may be akin to the view seen by Miller on February 15, 1944: Captioned,”Formation of North American B-25s of the 340th Bomb Group enroute to their target – Cassino. March 15, 1944,” the picture is United States Army Air Force photo “68261AC / A22901”, and can be found within the (appropriately) entitled collection “WW II US Air Force Photos“, at Fold3.com. The planes are aircraft of the 488th Bomb Squadron, the “give-away” being the “8C” (“8”, for 488th) code on the vertical tail of the aircraft in the left center.

But, Walter Miller did not participate on the day’s mission, for his name is absent from the 489th’s Loading List for March 15….

But, Walter Miller did not participate on the day’s mission, for his name is absent from the 489th’s Loading List for March 15….

____________________

____________________

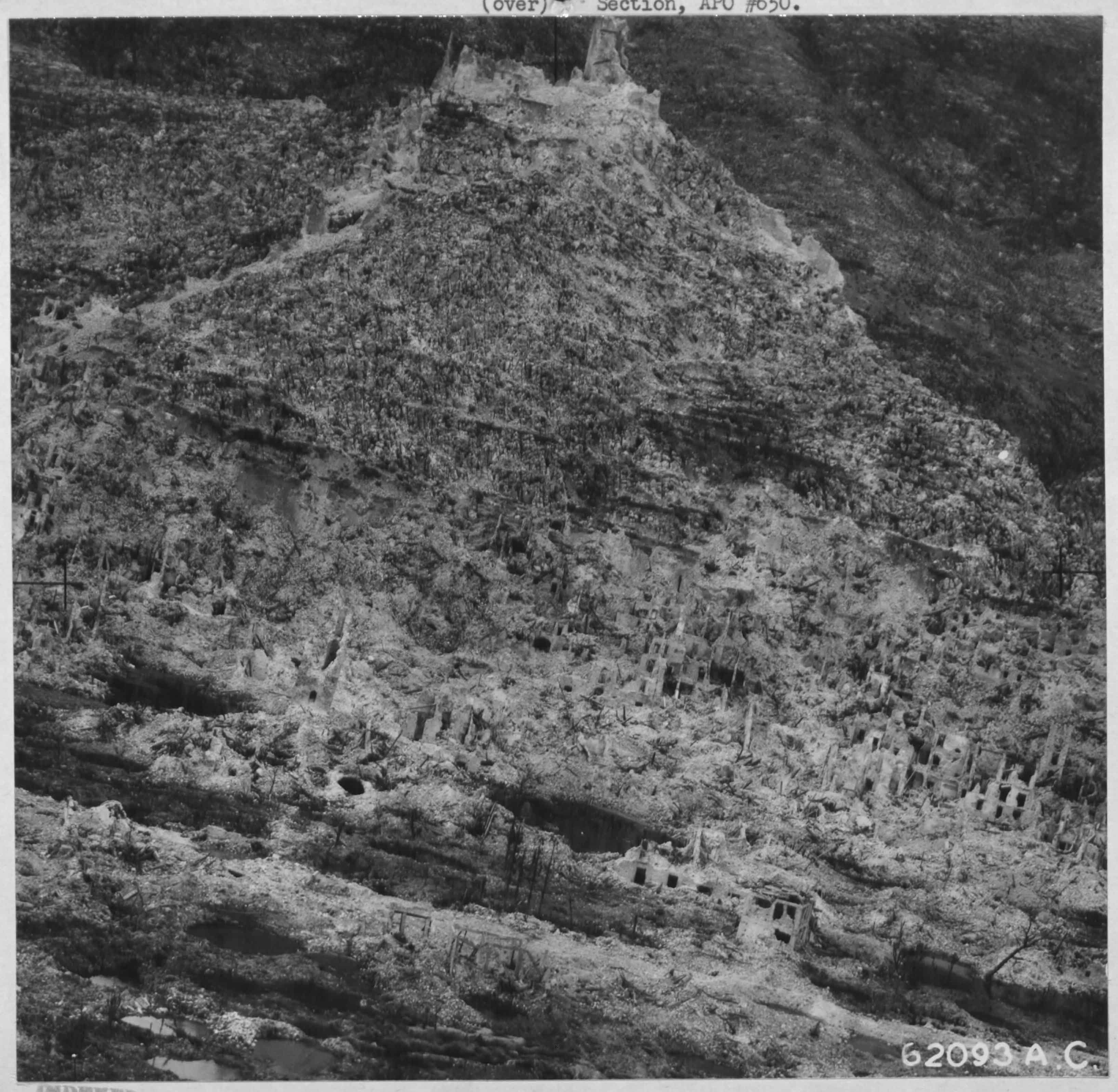

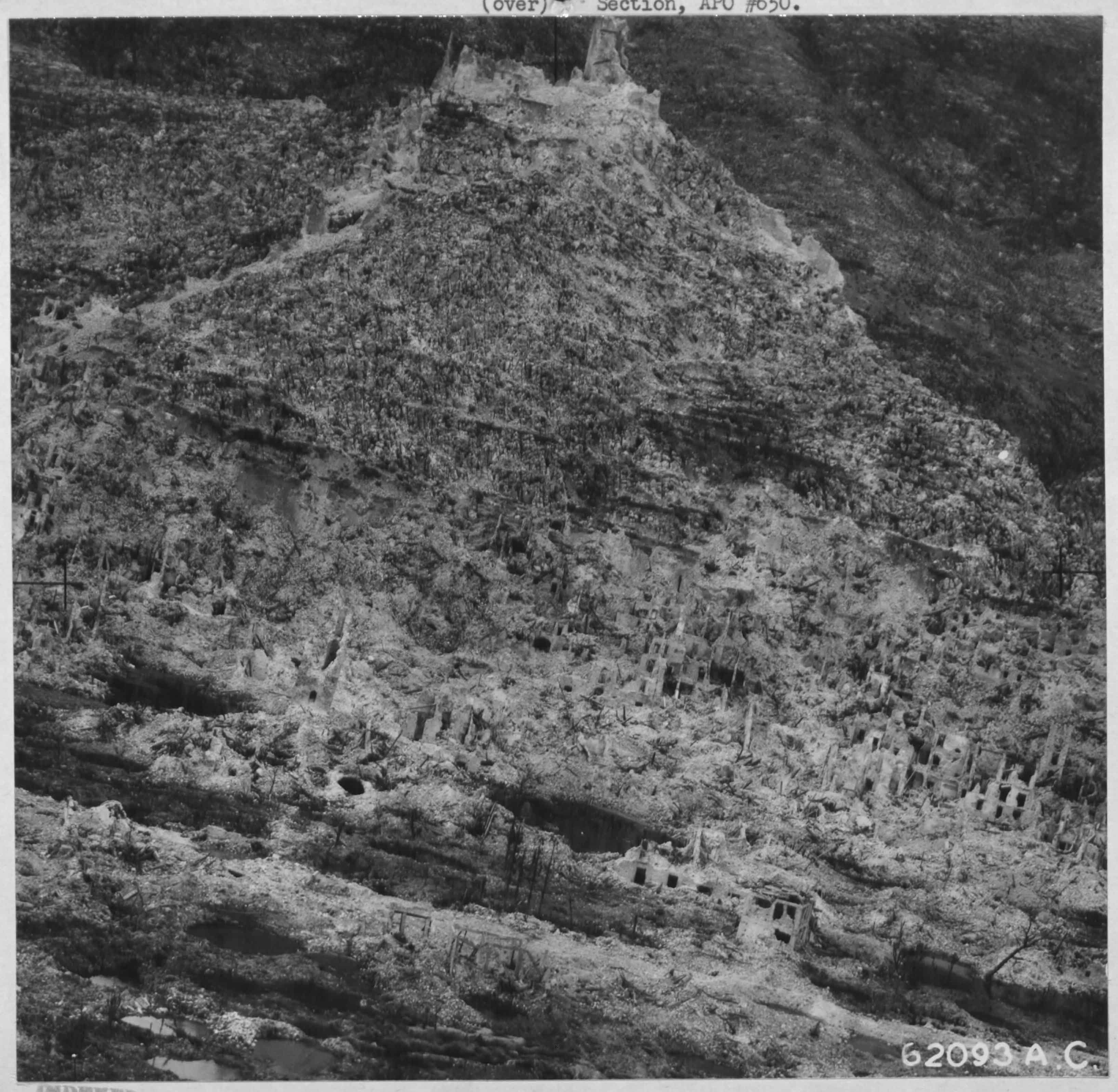

The results of war: A view of the remnants of the town of Cassino (foreground), and the hilltop abbey (upper center), in Army Air Force Photograph 62093AC / A25003. Curiously, the caption on the rear of the photo states, “Bomb damage to Monte di Cassino Abbey, Cassino, Italy, after bombing attacks by Allied planes. The centuries-old monastery had been used by the German defenders as a strong point to block the Allied drive on Rome,” but the words “Monte di Cassino Abbey” are crossed out.

The image is undated, but it was received by the Army Air Force or War Department in November of 1944.

________________________________________

________________________________________

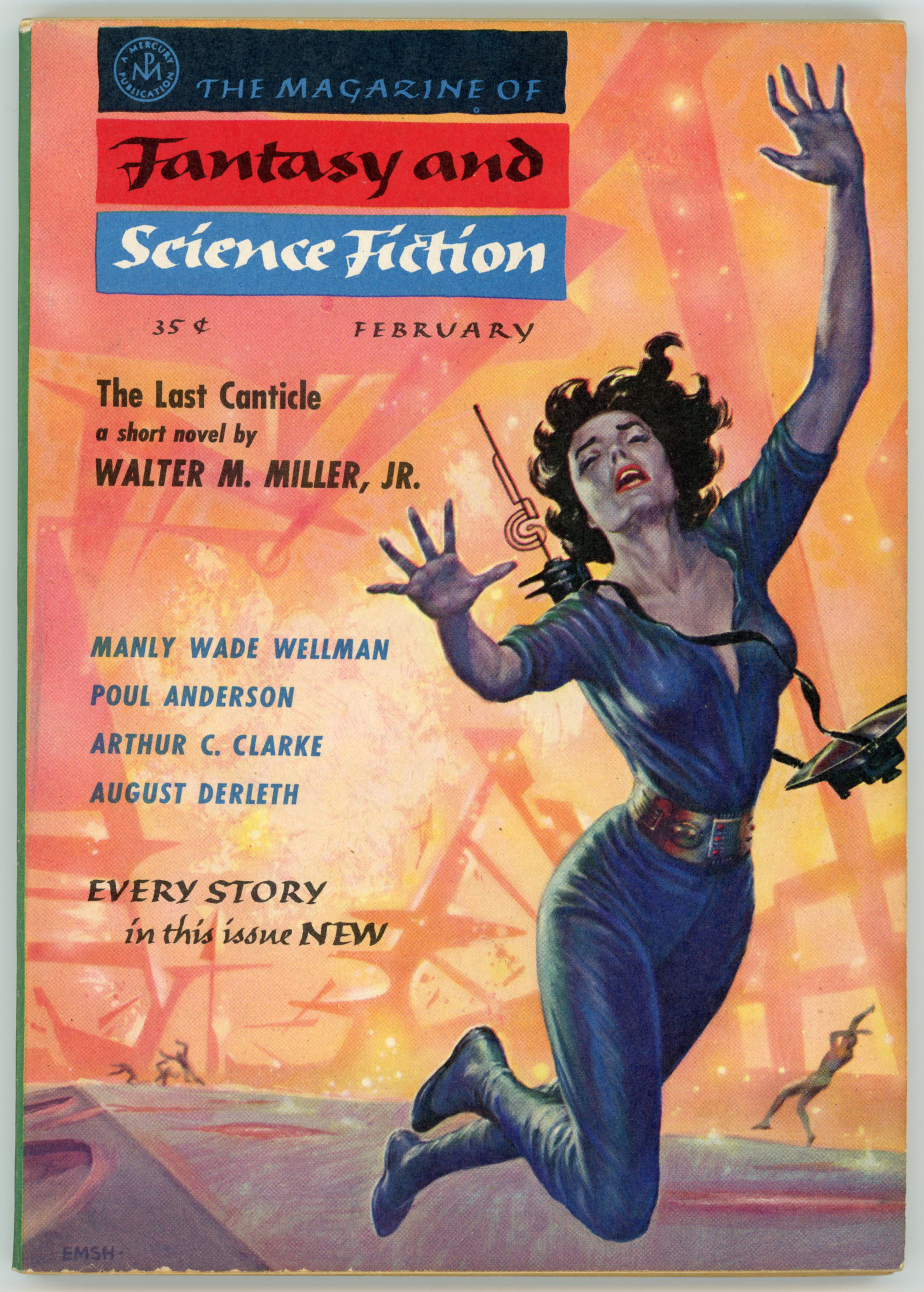

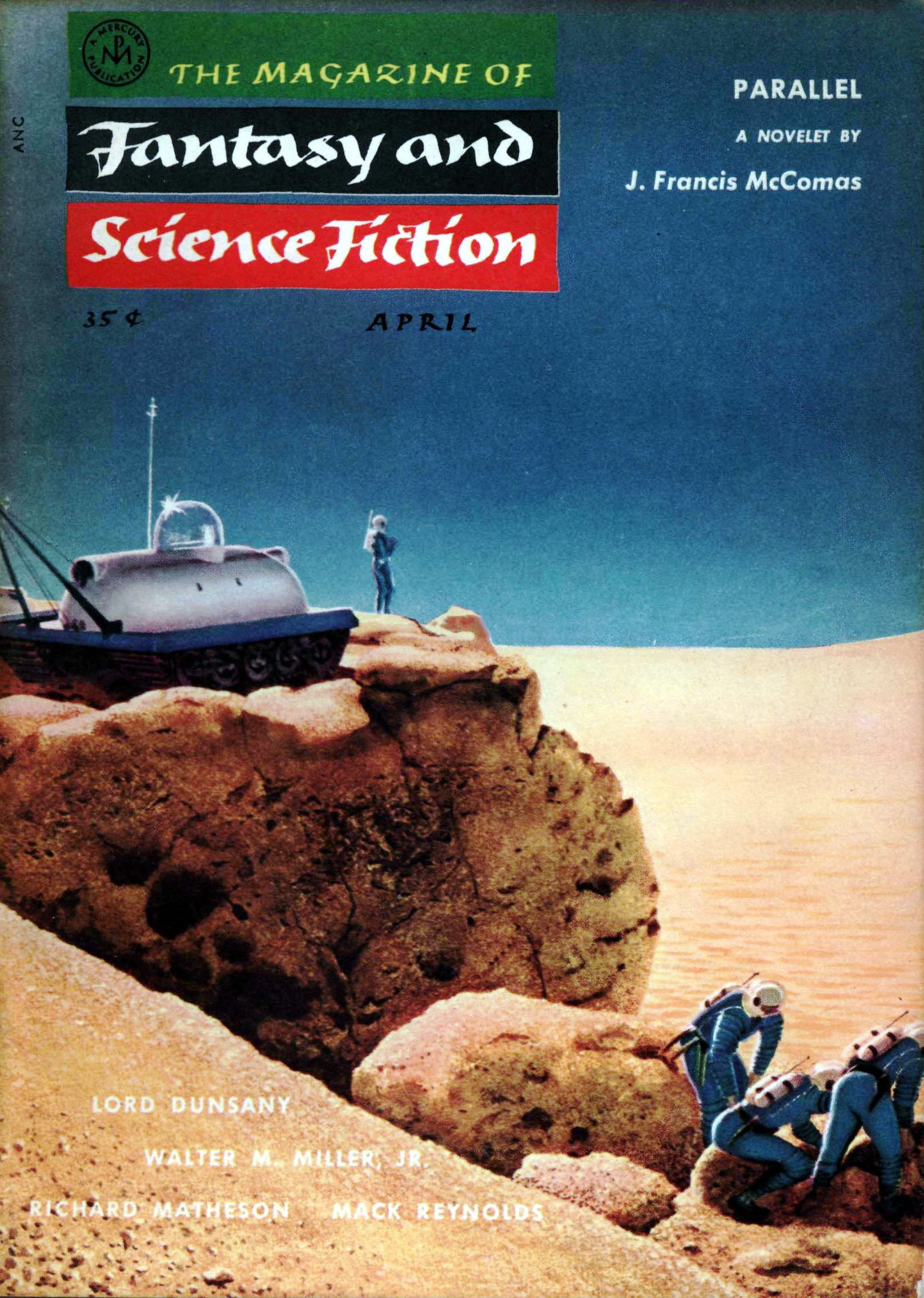

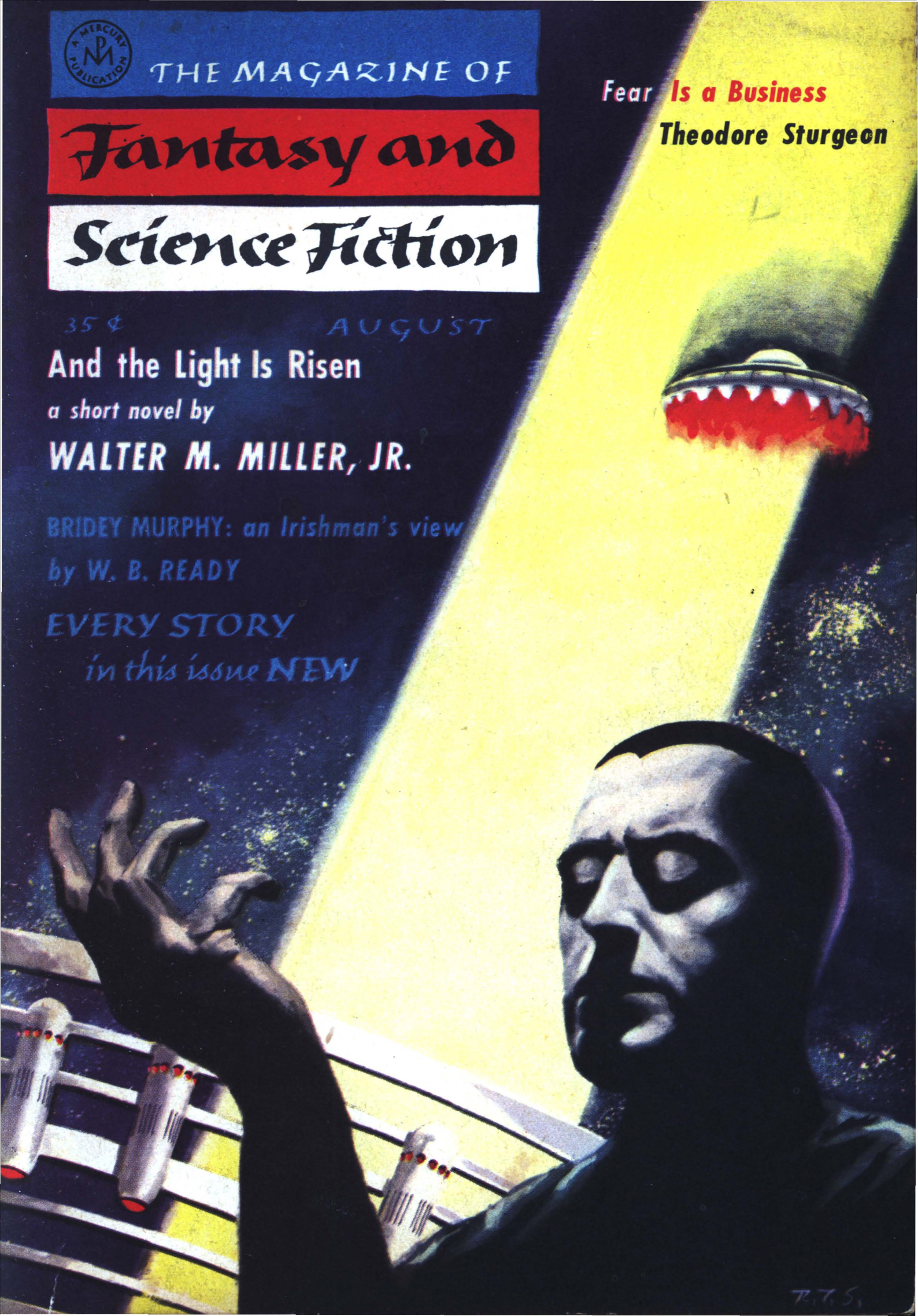

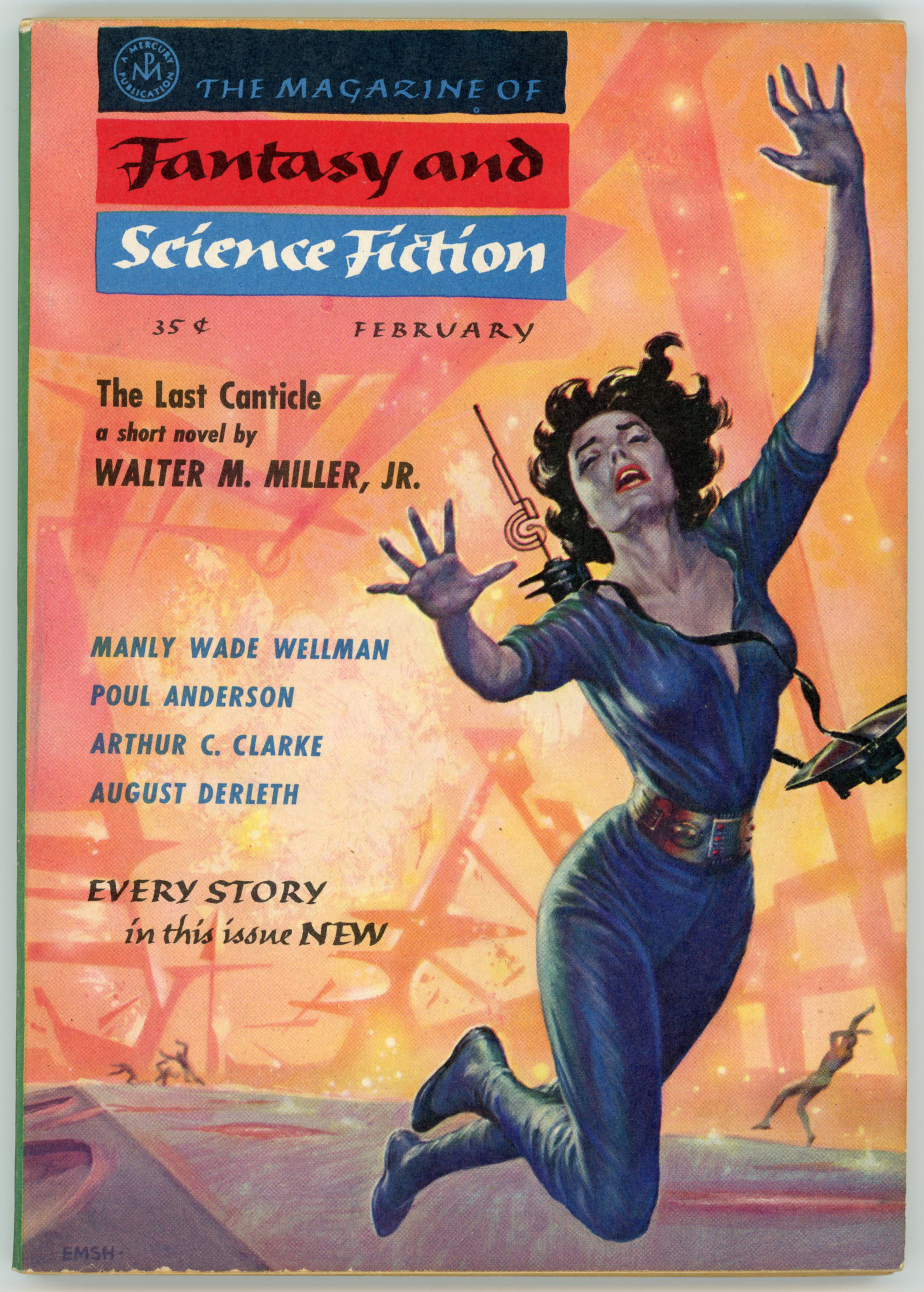

As mentioned in the Wikipedia entry for the novel, and, discussed by Alexandra H. Olsen, A Canticle for Leibowitz, published in October of 1959, was created by melding and altering elements, characters, concepts, and plot devices from his three previously published post-cataclysmic stories (all having appeared in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction) into a single work, and, adding passages in Latin.

The three stories which formed the basis of the novel were:

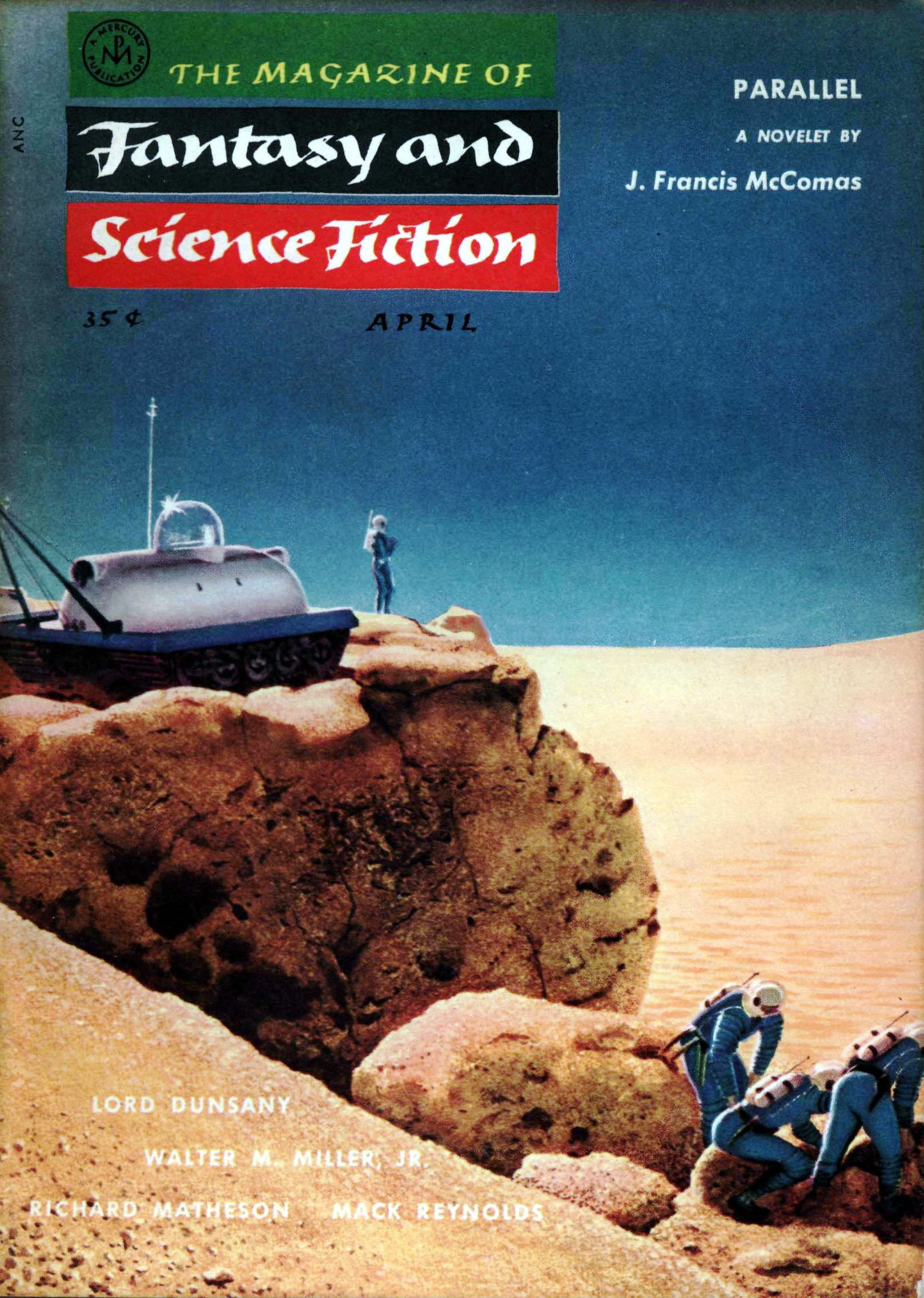

“A Canticle for Leibowitz”, published in April of 1955 (pp. 93-111)

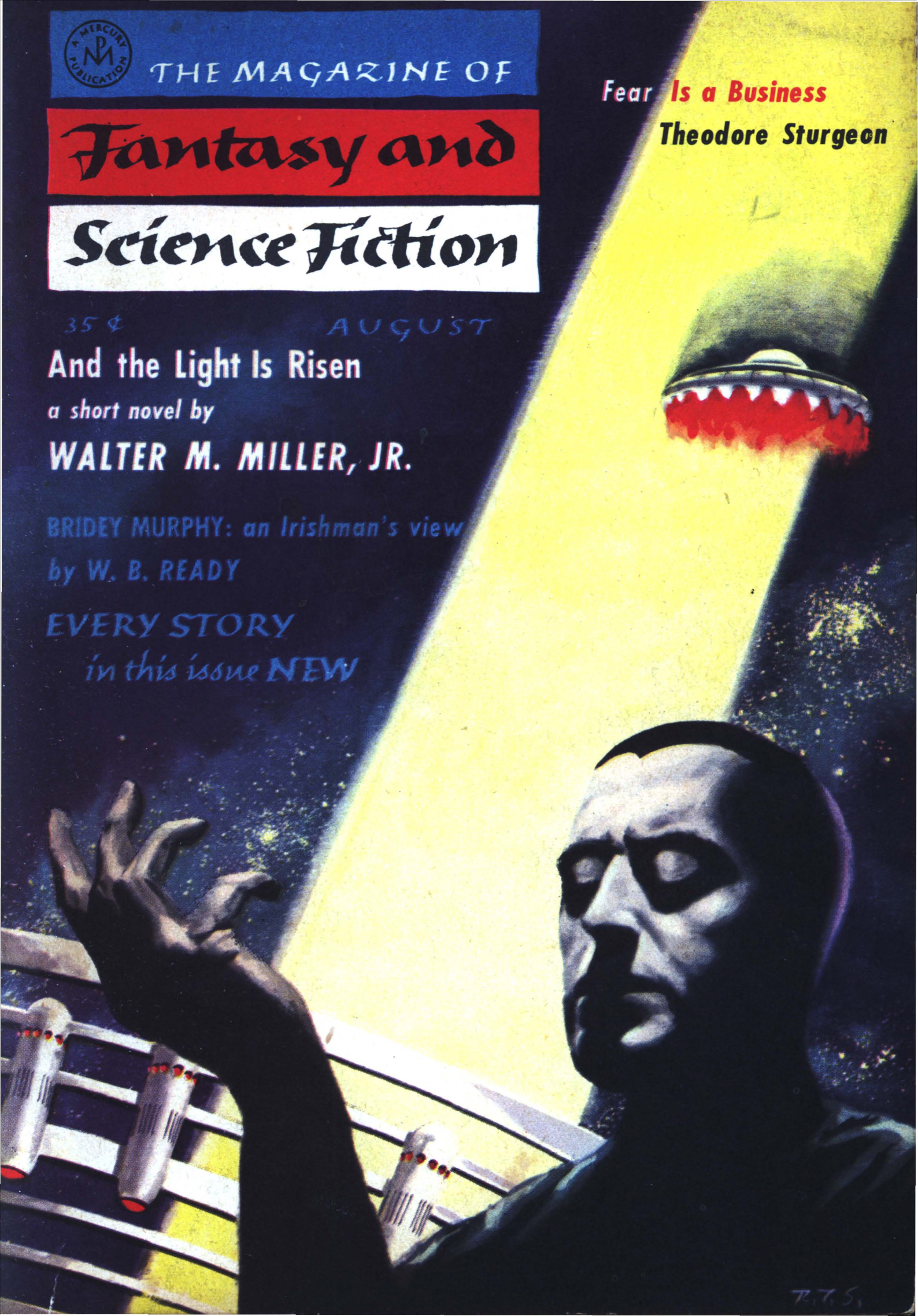

“And the Light Is Risen”, published in August, 1956 (pp. 3-80)

“The Last Canticle”, published in February, 1957 (pp. 3-50)

A final tale in the series, “God Is Thus”, appeared in Fantasy & Science Fiction in November of 1997 (pp. 13-51), thirty-eight years after the novel’s publication.

But…

…though the motivation for the ultimate creation of Canticle of 1955 was Miller’s participation in the bombardment of Monte Cassino, evidence for the emotional impact of that is clearly evident in an earlier story of a vastly different literary nature: This was “Wolf Pack”, which appeared in the September-October, 1953, issue of Fantastic. Among the thirty-eight works of short fiction listed in Miller’s biographical profile at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database, “Wolf Pack” was the 26th, while “Secret of the Death Dome”, published in Amazing Stories in 1951, was the first. “Wolf Pack” appeared two years before “A Canticle for Leibowitz’s” publication, in the 1955 The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction.

Though I’ve thus far barely (!) skimmed the story, it seems to belong entirely to the realm of fantasy as opposed to science fiction, for it relates a combat flyer’s confrontation with his conscience – himself? – on levels symbolic, psychological, and perhaps supernatural.

Do you want to read the story? Here’s a PDF version of “Wolf Pack”.

As for the artistic aspects of the Fantastic story – visual art, that is! – here’s the two-page opening illustration for the tale…

…and here’s an accompanying illustration, showing representations of a B-25 bomber (viewed from above) and a bombardier peering through a generic “black box” looking bombsight (not quite a Norden bombsight!), both visual elements being surrounded by symbolic vignettes of villages. Both pieces are by Bernard Krigstein, whose work is much more strongly associated with comic books than pulps.

________________________________________

Continuing on a theme of art, here’s the cover of Bantam Books’ 1961 paperback edition of the novel, which shows a monk against a backdrop of a destroyed city’s skyline. Though the artist’s name isn’t listed, perhaps he was Paul Lehr, given the era of the book’s publication, and, the visual style of the composition.

In terms of Miller’s use of Latin, here’s the prayer uttered by Brother Francis Gerard of The Albertian Order of Saint Leibowitz, which appears very early in the novel’s first part (“Fiat Homo”), during the Brother’s exploration of the remains of a fallout shelter somewhere in the American Southwest. The allusions to the actuality and legacy of nuclear war are explicit and vivid, and – recited in the format of prayer rather than prose, with each of the three central groups of verses being thematically linked – powerfully expressed and visually evocative.

In terms of Miller’s use of Latin, here’s the prayer uttered by Brother Francis Gerard of The Albertian Order of Saint Leibowitz, which appears very early in the novel’s first part (“Fiat Homo”), during the Brother’s exploration of the remains of a fallout shelter somewhere in the American Southwest. The allusions to the actuality and legacy of nuclear war are explicit and vivid, and – recited in the format of prayer rather than prose, with each of the three central groups of verses being thematically linked – powerfully expressed and visually evocative.

A spiritu fornicationis,

Domine, libera nos.

From the lighting and the tempest,

O Lord, deliver us.

From the scourge of the earthquake,

O Lord, deliver us.

From plague, famine, and war,

O Lord, deliver us.

From the place of ground zero,

O Lord, deliver us.

From the ruin of the cobalt,

O Lord, deliver us.

From the rain of the strontium,

O Lord, deliver us.

From the fall of the cesium,

O Lord, deliver us.

From the curse of the Fallout,

O Lord, deliver us.

From the begetting of monsters,

O Lord, deliver us.

From the curse of the Misborn,

O Lord deliver us.

A morte perpetua,

Domine, libera nos.

Peccatores,

te rogamus, audi nos.

That thou wouldst spare us,

we beseech thee, hear us.

That thou wouldst pardon us,

we beseech there, hear us.

That thou wouldst bring us truly to penance,

te rogamus, audi nos.

(pp. 14-15)

(In just a moment, Brother Gerard will discover a relic from the life of Saint Leibowitz…)

________________

________________

________________

Of the larger folded papers, one was tightly rolled as well,

and it began to fall apart when he tried to unroll it;

he could make out the words RACING FORM, but nothing more.

After returning it to the box for later restorative work,

he turned to the second folded document;

its creases were so brittle that he dared inspect only a little of it,

by parting the folds slightly and peering between them.

A diagram, it seemed, but – a diagram of white lines on dark paper!

Again he felt the thrill of discovery.

It was clearly a blueprint

– and there was not a single original blueprint left at the abbey,

but only inked facsimiles of several such prints.

The originals had faded long ago from overexposure to light.

Never before had Francis seen an original,

although he had seen enough hand-painted reproductions to recognize it as a blueprint,

which, while stained and faded,

remained legible after so many centuries because of the total darkness and low humidity in the abbey. He turned the document over – and felt brief fury:

What idiot had desecrated the priceless paper?

Someone had sketched absent-minded geometrical figures and childish cartoon faces all over the back. What thoughtless vandal-

The anger passed after a moment’s reflection.

At the time of the deed, blueprints had probably been as common as weeds,

and the owner of the box the probably culprit.

He shielded the print from the sun with his own shadow while trying to unfold it further.

It the lower right-hand corner was a printed rectangle containing,

in simple block-letters, various titles, dates, “patent numbers”, reference numbers, and names.

His eye traveled down the list until it encountered:

“CIRCUIT DESIGN BY: Leibowitz, I.E.”

He closed his eyes tightly and shook his head until it seemed to rattle.

Then he looked again.

There is was, quite plainly:

“CIRCUIT DESIGN BY: Leibowitz, I.E.”

He flipped the paper over again.

Among the geometric figures and childish sketches,

clearly stamped in purple ink,

was the form:

The name was written in a clear feminine hand,

not in the hasty scrawl of the other notes.

He looked again at the initialed signature of the note in the lid of the box,

I.E.L. – and again at “CIRCUIT DESIGN BY …”

And the same initials appeared elsewhere throughout the notes.

(Proof of the Saint’s existence! Here’s the “Circuit Design Form” bearing his signature, from page 23 of the Bantam paperback. Absent from “Canticle” in the 1955 edition of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, in book form, it really catches the reader’s attention.)

There had been argument, all highly conjectural,

There had been argument, all highly conjectural,

about whether the beautiful founder of the Order, if finally canonized,

should be addressed as Saint Isaac or as Saint Edward.

Some even favored Saint Leibowitz as the proper address,

since the Beatus had, until the present, been referred to by his surname.

“Beate Leibowitz, ora pro me!” whispered Brother Francis.

His hands were trembling so violently that they threatened to ruin the brittle documents.

He had uncovered relics of the Saint. (pp. 22-24)

________________________________________

Given the novel’s success, it’s unsurprising that it was adapted for radio broadcast. It’s available via Archive.org, at The Classic Archives Old Time Radio Channel, and Old Time Radio Downloads.

Created in 1981, the play is comprised of fifteen segments, each of roughly a half-hour duration. The informational blurb at Archive.org states, “The radio drama adaptation by John Reed, and produced at WHA by Carl Schmidt and Marv Nunn. The play was directed by Karl Schmidt, engineered by Marv Nunn with special effects by Vic Marsh. Narrator – Carol Collins and includes Fred Coffin, Bart Hayman, Herb Hartig and Russel Horton. Music was by Greg Fish and Bob Budney and the Edgewood College Chant Group.”

________________________________________

________________________________________

These are covers of the three 1950’s issues of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in which appeared the three stories from which were derived Miller’s novel, and, the cover of Fantasy & Science Fiction in October-November of 1997, which was the venue for the last story in the series. Ironically, none of the four issues feature cover art actually pertaining to Miller’s stories or novel. Much the same was so for 1951 issue of Galaxy Magazine in which appeared Ray Bradbury’s “The Fireman”, later published in book form as Farhenheit 451: That issue featured cover art by Chesley Bonestell.

__________

The cover of the April, 1955 issue features a close-up from Chesley Bonestell’s stunning panorama “Mars Exploration”. Notice that the painting shows a strip of green – vegetation – at the base of weathered background hills. Well, this was the mid-1950s, over a decade before Mariner probes revealed the true nature of the Martian surface. Then again, maybe Mars is “green”, but a deeper, below-the-surface kind of green?

“A Canticle for Leibowitz”

April, 1955

____________________

____________________

“Mars Exploration”, by Chesley Bonestell

________________________________________

________________________________________

“And the Light Is Risen”

August, 1956

________________________________________

________________________________________

“The Last Canticle”

February, 1957

________________________________________

________________________________________

“God Is Thus”

October-November, 1997

________________________________________

________________________________________

References, Readings, and What-Not…

57th Bomb Wing, at 57thBombWing.com

340th Bomb Group History, at 57thBombWing.com

489th Bomb Squadron History, at 57thBombWing.com

489th Bomb Squadron History for February, 1944 (PDF Transcript), at 57th BombWing.com

489th Bomb Squadron insignia, at RedBubble.com

Bernard Krigstein, at Wikipedia

Walter M. Miller, Jr., at Wikipedia

Walter M. Miller, Jr., at Internet Speculative Fiction Database

“A Canticle for Leibowitz”, at Wikipedia

“Mars Exploration” (painting), by Chesley Bonestell, at RetroFuturism (subreddit)

The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (covers for April, 1955, August, 1956, and October-November, 1997), at Pulp Magazine Archive (Archive.org)

Bond, Harold L., Return to Cassino, Pocket Books, Inc., New York, N.Y., March, 1965

Bowden, Denny, Secret Life / Death of the Author of the Greatest Science Fiction Novel – Born in New Smyrna, Died in Daytona Beach, at VolusiaHistory.com

Majdalany, Fred, The Battle of Cassino, Ballantine Books, Inc., New York, N.Y., 1957

Olsen, Alexandra H., Re-Vision: A Comparison of Canticle for Leibowitz and the Novellas Originally Published, Extrapolation, Summer, 1997

Piekalkiewicz, Janusz, Cassino – Anatomy of the Battle, Orbis Publishing, London, England, 1980

Roberson, William H., Walter M. Miller, Jr.: A Reference Guide to His Fiction and His Life, McFarland and Company, Inc., Jefferson, N.C., 2011

Webley, Kayla, Top Ten Post-Apocalyptic Books: A Canticle for Leibowitz, Time, June 7, 2010

Flight Lieutenant Cecil Frederick “Jimmy” Rawnsley

Flight Lieutenant Cecil Frederick “Jimmy” Rawnsley