This post has been updated to include Tom Ferrell’s laudatory review of Those Who Fall, from The New York Times Book Review. The review follows…

‘I Drop Bombs. That’s My Job’

THOSE WHO FALL

By John Muirhead.

Illustrated. 258 pp. New York:

Random House. $18.95.

By Tom Ferrell

The New York Times Book Review

February 15, 1987

PEOPLE who have been in battle have a claim on our attention, as the Vietnam veterans keep insisting. This is not because we are grateful, or even because we should be. There’s a terrible disproportion between risk and gain, increasing with time. The Americans in a World War I cemetery lost all they had to lose, but it would be a bold and speculative accountant of history who might try to show just how we are better off in 1987 for men who died very young in 1917.

John Muirhead isn’t dead, though men were killed in his plane and more than enough airmen went down in flames before his eyes. He too has trouble defining his claim on our attention. This is how “Those Who Fall” begins:

“I suppose I am like most men who soldiered for a time. I think that something unusual happened to me; some particular meaning was revealed to me so I should set it down. Men have been boring their wives, their children, and other men with these kind of stories from Marathon through Chickamauga, and I’m no different from the lot. Having survived it all, I can’t leave well enough alone, but must ponder on it and remember and talk at least about one part of it that was, I think, a kind of glory.”

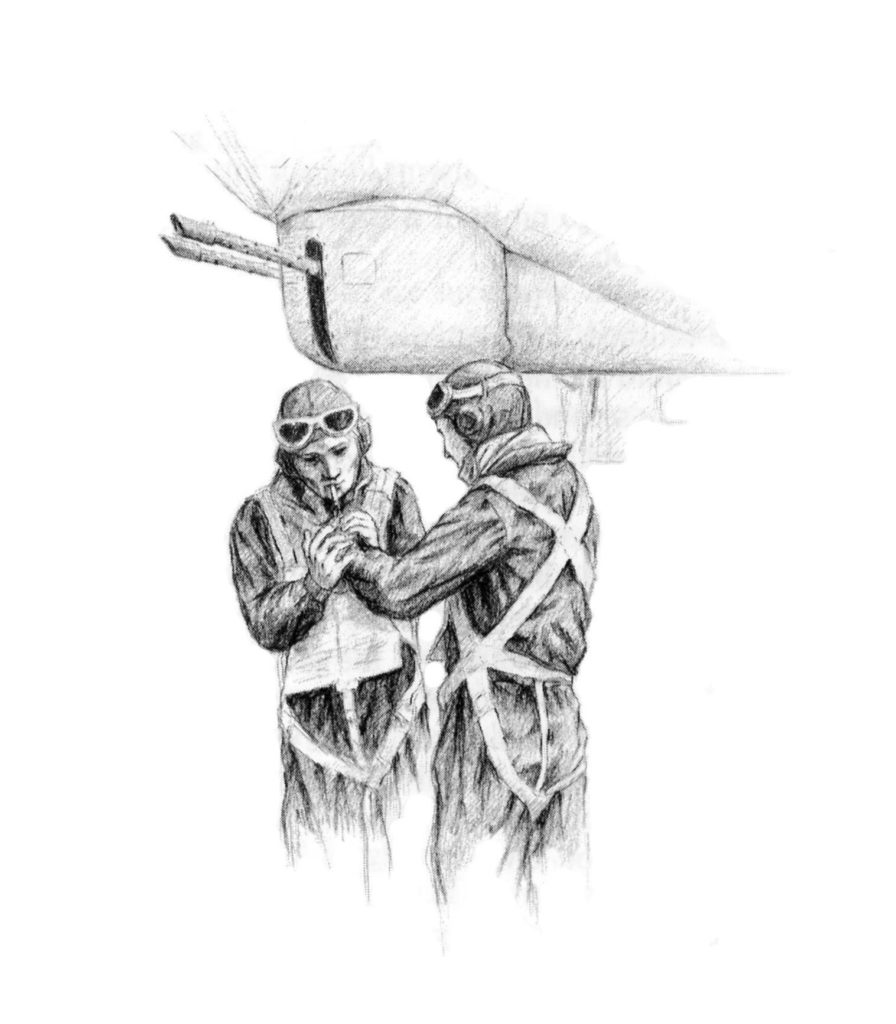

Mr. Muirhead, whose first book this is, is now a retired engineer. In early 1944 he was a B-17 pilot based near Foggia, Italy, flying missions up the Adriatic and over the Alps to targets like Regens-burg, Munich and Wiener Neustadt. For combat soldiers, the men of his heavy bomber group enjoyed reasonable material conditions: hot meals, dry beds in which they could safely sleep, even hot water at times. Then they would rise, before dawn, to start a long day’s ride over an armed and hostile industrial society, 10 men in a contraption 75 feet long and weighing not all that much more than a New York City bus.

The chief hazards were fighters – Germany still had at that time enough planes, pilots and fuel to mount a vigorous defense – and flak. “We edged past Pola,” Mr. Muirhead writes, “and were saluted with a barrage of flak that for all but a few bursts fell short of the low-left squadron. Three stray shells exploded in the center of the formation. I could see the orange flame in the middle of the black puffs. Two successive bursts erupted off the tip of our right wing and magically an array of star-shaped holes appeared in our windshield. … It never seemed to us that the flak came from anything on the ground. Not from guns that men fired. Flak came from the sky itself; it blossomed there.” Things got rapidly worse and stayed worse for hours; on this trip to Regensburg, a particularly horrible one, Mr. Muirhead’s left waist gunner was killed, one engine was shot out and his group lost 11 of 21 planes.

• • •

Fear and self-induced amnesia became the poles of Mr. Muirhead’s service life. He avoided knowing the other members of his crews. He tells us, repeatedly, that he forgot why the war was being fought and didn’t want to know. “I work in this little parish,” he tells a nonflying officer friend. “I’m employed to fly a bomber from here to there. I drop some bombs there, and then I come back here – if I’m lucky. That’s my job; I’m used to it.”

On June 28, 1944, he was shot down over Bulgaria, surviving with most of his crew. Defeat brought a kind of relief, but apparently not only because capture enhanced his chances of living out the war. “Peace and comradeship,” he writes, could now replace professional relations among his crew and his new acquaintances in captivity. Though he nowhere says so, I suspect he was glad to see his responsibility diminished. Another pilot’s error in formation that had destroyed two B-17s and 20 men returns oppressively to his memory several times in his narrative.

His P.O.W. camp was atop a hill, with splendid views; but life in it was very lousy, literally. Also hungry and unmedicated, though it isn’t clear that his Bulgarian captors were in much better case; the Germans had stripped their unfortunate ally to support their own military machine as their situation deteriorated on both fronts. In September, with the Russians massed on the Bulgarian border, the camp commandant opened the gate and released the prisoners. What happened after that Mr. Muirhead doesn’t say.

WE haven’t been bored; the battle stuff has been keenly drawn, the terror and desperation, some of it quiet, are as real as can be. There’s a lot of soldierly helling around and a lot of funny obscene conversation, funny in the way reflex obscenity can be when it supplants or augments official military jargon (there’s also a lot of effortful, quasi-poetic writing, much of which deserves good marks for trying). And there’s enough nuts-and-bolts matter about caring for planes and running the squadron to fix the whole tale solidly in the slot of 1944 material technology. All excellent of its kind, and it is a kind, the kind that feeds little bookstores and catalogue houses specializing in “militaria” and “aeronautica.”

But what about the glory? Promised at the start, it begins to glimmer in the P.O.W. camp when the men win a tiny victory over toilet regulations. “To endure we sought to win such trifles to measure the day. We had become aliens of the poorest kind, and we had to find more than bits of bread to live on. … The last hour, the last minute, the last second of the last day, would come to pass, opening the way for us. That would be the moment of our glory, our long-remembered glory.” And so it proved, when Mr. Muirhead and two comrades, with four legs among them, walked out the prison gate and across their hilltop – a victory parade without a band. Military memoirs don’t dare to dress themselves in glory much any more, and maybe you had to be there, but Mr. Muirhead has the courage to trust his memories. I’m convinced he was there.

Tom Ferrell is an editor of The Book Review.

I suppose I am like most men who soldiered for a time.

I suppose I am like most men who soldiered for a time.

I think that something unusual happened to me;

some particular meaning was revealed to me so I should set it down.

Men have been boring their wives,

their children,

and other men with these kind of stories from Marathon through Chickamauga,

and I’m no different from the lot.

Having survived it all, I can’t leave well enough alone,

but must ponder on it and remember and talk at least about one part of it that was, I think,

a kind of glory.

On the twenty-third of June, 1944,

I ended my time as a bomber pilot flying out of Italy with the 301st Bomb Group,

and became a prisoner of war in Bulgaria.

My last mission was to Ploesti.

Although that name had its own dreadful sound,

the other places and other names all took their toll

whether you feared them or not.

It mattered very little when you finally bought it.

The odds were, one always knew, that something was going to happen.

It was not felt in any desperate way,

but rather it came as a difference in consciousness

without one’s being aware of the change.

In the squadron we learned to live as perhaps once we were long ago,

as simple as animals without hope for ourselves or pity for one another.

Completing fifty missions was too implausible to even consider.

An alternative, in whatever form it might come, was the only chance.

Death was the most severe alternative.

It was as near as the next mission,

although we would not yield to the thought of it.

We would get through somehow: maybe a good wound,

or a bail-out over Yugoslavia or northern Italy; the second front might open up,

and the Germans might shift all their fighters to the French coast.

We might even make it through fifty missions – a few did.

But such fantasies didn’t really persuade us,

not with our sure knowledge that we were caught in a bad twist of time

with little chance we would go beyond it.

Our lives were defined by a line from the present

to a violent moment that must come for each of us.

The missions we flew were the years we measured to that end,

passing by no different from any man’s except we became old and died soon.

I don’t know whether any of this is true or not.

Everything happened that I have said happened,

but it’s memory now, the shadow of things.

The truth lives in its own time, recall is not the reality of the past.

When friends depart, one remembers them but they are changed;

we hold only the fragment of them that touched us and our idea of them,

which is now a part of us.

Their reality is gone, intact but irretrievable,

in another place through which we passed and can never enter again.

I cannot go back nor can I bring them to me;

so I must pursue the shadows to some middle ground,

for I am strangely bound to all that happened then.

We broke hard bread together and I can’t forget:

Breslau, Steyr, Regensburg, Ploesti, Vienna, Munich, Graz,

and all the others; not cities,

but battlegrounds five miles above them where we made our brotherhood.

It’s gone and long ago; swept clean by the wind, only some stayed.

Part of me lives there still, tracing a course through all the names.

I don’t know why.

What is it that memory wants that it goes through it all again?

Was there something I should have recognized?

Some terrible wisdom?

The kind of awful knowledge that stares out of the eyes of a dying man?

I was at the edge then and almost grasped the meaning,

but I lived and failed the final lesson and came safe home.

I linger now, looking back for them, the best ones who stayed and learned it all.

“It was as if in greeting that three of the tiny creatures came out from the boards around the stove and scurried toward me. I was sitting on Mac’s bunk. He used to feed them crumbs every time he came in the tent. A fourth mouse joined his friends and, while they nibbled happily, I began the sad chore of going through Mac’s belongings.” (pp. 66-67)

“It was as if in greeting that three of the tiny creatures came out from the boards around the stove and scurried toward me. I was sitting on Mac’s bunk. He used to feed them crumbs every time he came in the tent. A fourth mouse joined his friends and, while they nibbled happily, I began the sad chore of going through Mac’s belongings.” (pp. 66-67)

“I don’t have any damn matches.”

“I don’t have any damn matches.”

“I handed him mine. He took them without a word; he struck five of them before he got the pipe going. He had forgotten his cigarette, which was still smoldering on the bomb cart where he had placed it.” (p. 114)

“The ground was rushing up at me! I was moving toward a high ridge! I swept over it, and then I plunged through the upper branches of a giant pine; mu chute caught and was held fast while my inertia drove me over a deep, rocky gorge. My forward motion was violently snubbed, and I was sent rushing back toward a massive trunk. I missed it by three feet, but continued to swing wildly beside it. After a time, the motion ceased. I hung there over the steep incline of the gorge. The base of the tree reached deep into the slope; it was much too far to drop.” (p. 194)

__________

In this strange life, we lived in the narrow dimension of the present.

We didn’t seek the future, for it was not there;

and if we could not move into it or beyond it,

we could not return to our past.

We were dull and listless,

but we did not have the true languor of young men

whose dreams were of worlds ahead of them,

and who saw the present only as prelude to it.

If we were without dreams, without a past or a future,

and were caught in the stillness of the present,

our vision then became wise.

There was peace in the absence of clamor;

there was serenity in the days without battles.

If this tattered place where we lived

were to be the full measure of our lives,

we would find some sweetness in it.

A small mouse nibbling a piece of biscuit in my tent

was as wondrous as a unicorn.

The soiled streets of Foggia were full of light,

and one time when I was walking there,

I heard the pure voice of a woman singing.

I learned each day of the goodness of life.

I cherished what was given to me,

holding it just for the moment it was given,

for I knew it was fragile and could not be held for long.

__________

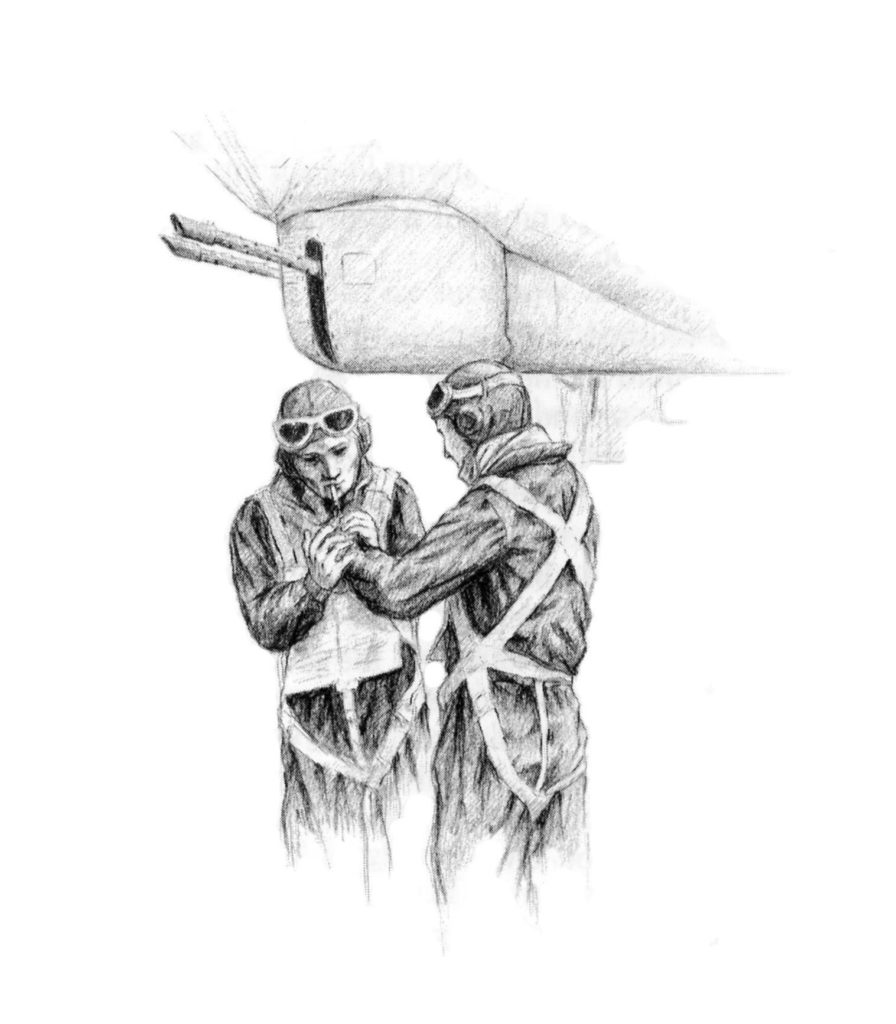

The Muirhead crew prior to departure for Italy. Author John Muirhead is in front row, far left, holding headphones. Notice that the aircraft in the background is a B-24 Liberator, which the author initially flew before assignment to the 301st Bomb Group. (USAAF photo, from dust jacket of Those Who Fall.)

The Muirhead crew prior to departure for Italy. Author John Muirhead is in front row, far left, holding headphones. Notice that the aircraft in the background is a B-24 Liberator, which the author initially flew before assignment to the 301st Bomb Group. (USAAF photo, from dust jacket of Those Who Fall.)

The Missing Air Crew Report (MACR) – #16203 – covering the author’s final mission: Target Ploesti, Roumania – Date June 23, 1944. John Muirhead, as pilot, is listed first in the crew roster.

The Missing Air Crew Report (MACR) – #16203 – covering the author’s final mission: Target Ploesti, Roumania – Date June 23, 1944. John Muirhead, as pilot, is listed first in the crew roster.

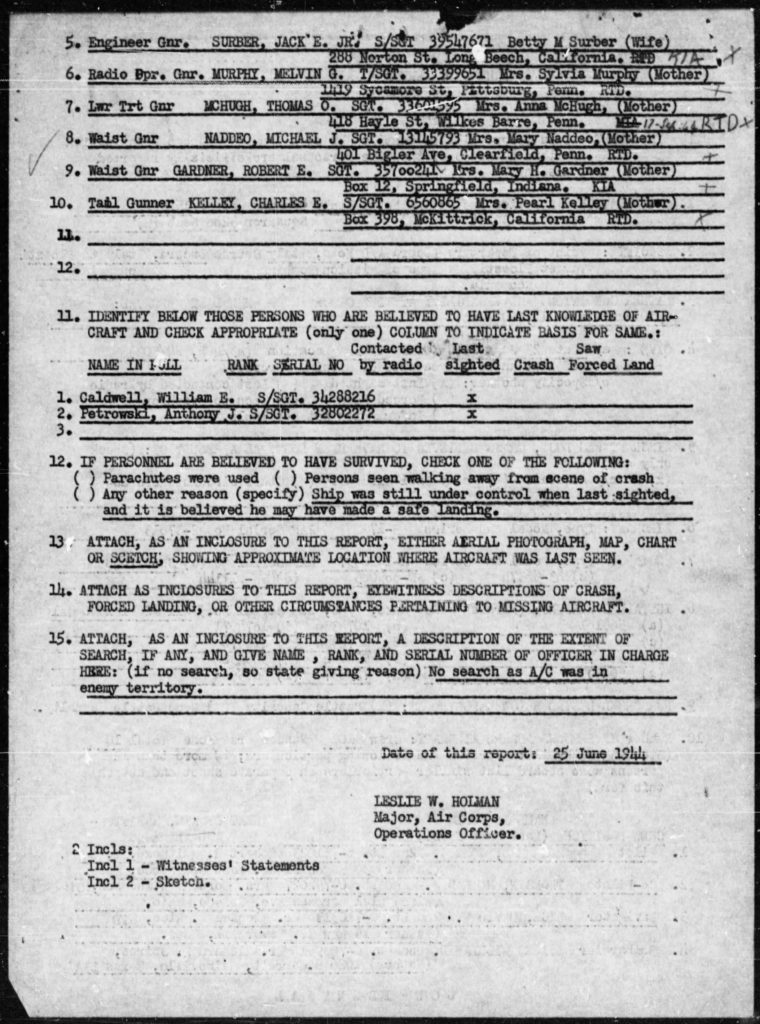

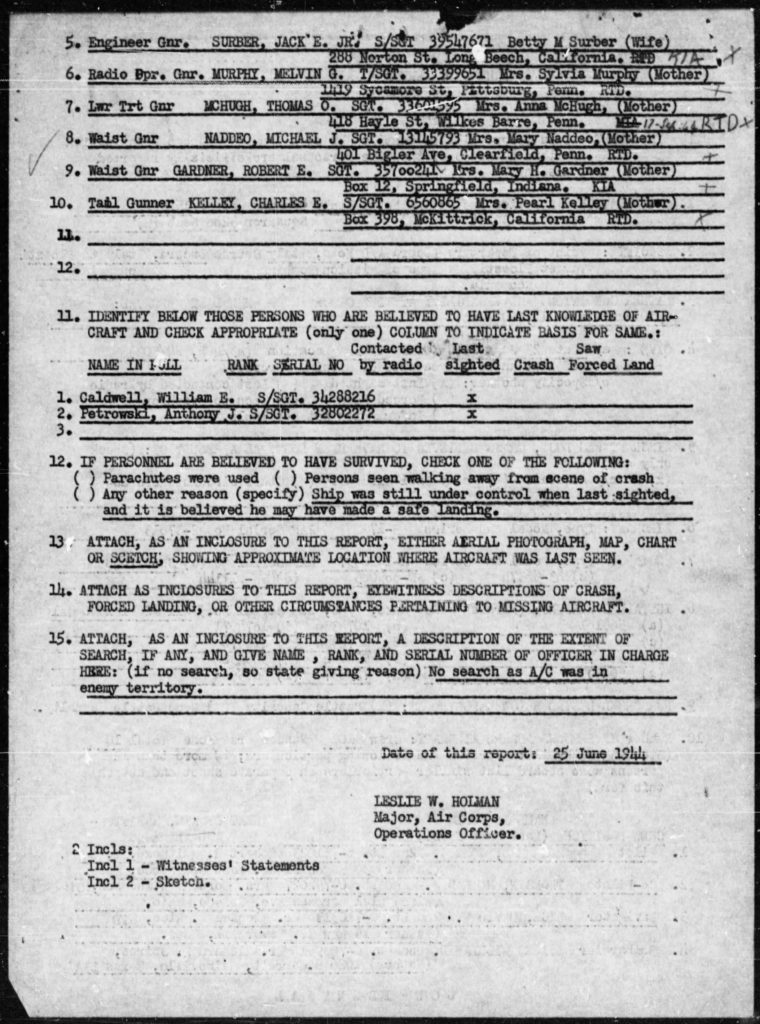

The second page of the MACR, listing the crew’s enlisted personnel (flight engineer, radio operator, and aerial gunners).

The second page of the MACR, listing the crew’s enlisted personnel (flight engineer, radio operator, and aerial gunners).

Eyewitnesses to the loss of Muirhead’s B-17, S/Sgt. William E. Caldwell and S/Sgt. Anthony J. Petrowski.

Eyewitnesses to the loss of Muirhead’s B-17, S/Sgt. William E. Caldwell and S/Sgt. Anthony J. Petrowski.

John Muirhead, mid-1980s.

John Muirhead, mid-1980s.