(Created in March of 2021, I’ve now updated this post to include the cover of Ballantine Books’ 1968 paperback edition of General Vasiliy Chuikov’s The Battle for Stalingrad. See below…)

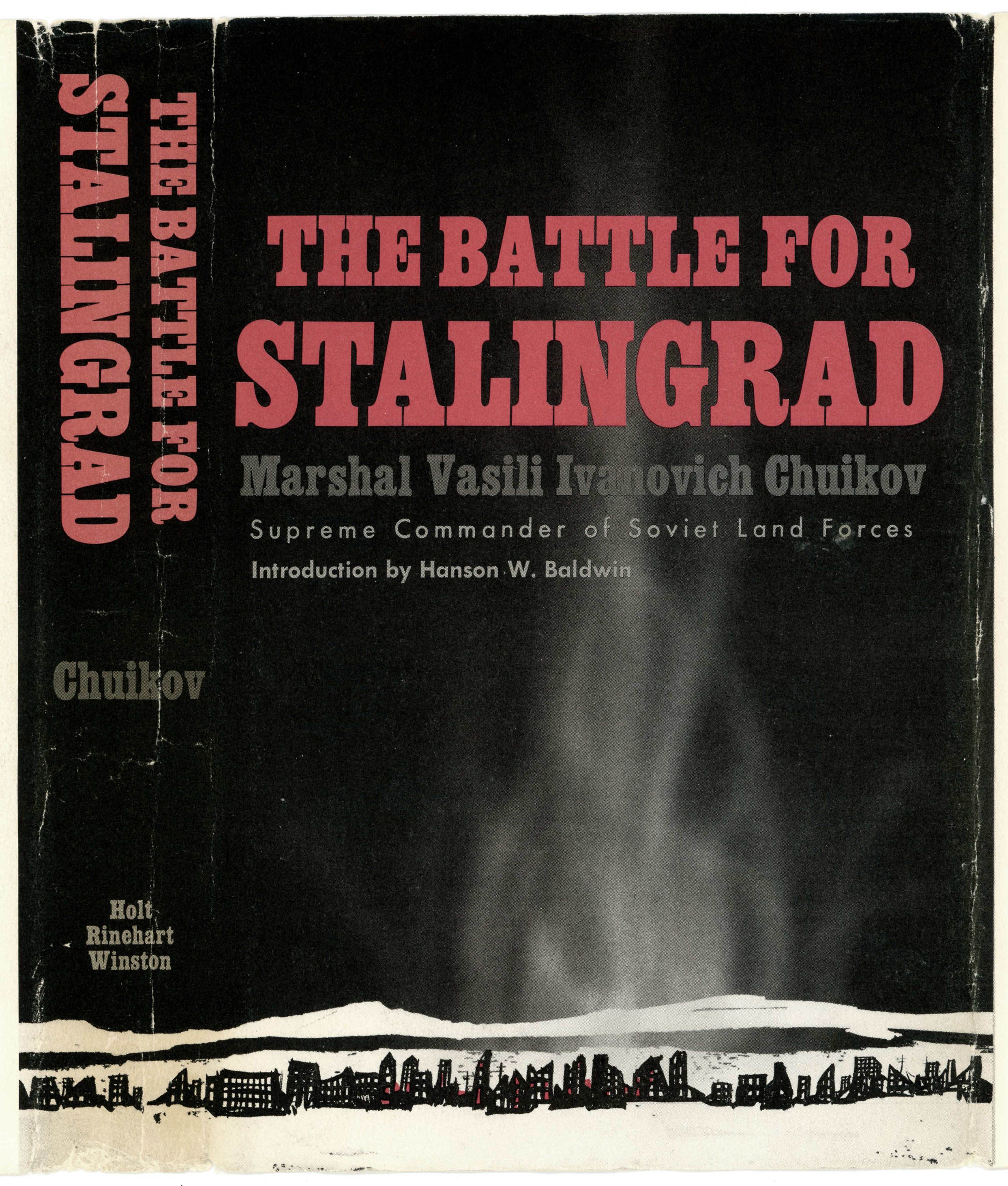

The cover design of Holt, Rinehart and Winston’s 1964 English-language translation of Russian General Vasiliy I. Chuikov’s The Battle for Stalingrad is simple, subtle yet powerful. As seen in my (rather bedraggled!) copy below, most of the cover is occupied by a black (not blue, not gray, not red) sky, empty except for a translucent pillar of white smoke rising from the ground below. And, that “ground” is not simply “ground”, but the ragged skyline of a destroyed city, with a river and hills behind: The city of Stalingrad (once Volgograd, and again Volgograd) on the banks of the Volga River.

Akin to other works of military history published in the 50s and 60s (such as Day of Infamy and We Die Alone) the book’s cover interior includes situation maps illustrating the location of military forces pertinent to the book.

The book also includes several photographs (some posed publicity images, some portraits, some random images of the battle) of which I’m showing two, here: A meeting between General Chuikov and his military commanders during November, 1942, and the General’s encounter with famous the sniper Vasiliy Zaytsev.

__________

From the book: “(Left to right) General N. Krylov, Lt.-General V. Chuikov, Lt.-General K. Gurov, and Major-General A. Rodimtsev discussing strategy in a bunker. (Camera Press)”

A much better image of the same meeting appears in William Craig’s 1974 Enemy At The Gates, albeit the four commanders have different poses and facial expressions, thus indicating that at least these two – and perhaps more, yet unknown? – photographs were taken of this event.

The caption: “Leaders of the Russian Sixty-second Army in command bunker near the Volga. From left to right: General Nikolai Krylov, Chief of Staff; General Vassili Chuikov, Commander; Kuzma Gurov, Political Commissar; General Alexander Rodimtsev, commander of the 13th Guards Division. (Note the severe eczema on Chuikov’s bandaged hand, caused by nervous tension which mounted as the war progressed.)”

Here are General Chuikov’s two military award citations:

__________

Here’s another image from Chuikov’s book: “The celebrated Russian sharpshooter, Vassili Zaitsev (far right), looks on as General Vassili Chuikov examines the lethal weapon. Commissar Kuzma Gurov is at center.” (Enemy at The Gates)”. As you can see from the innumerable WW II-era images of Zaytsev, his face bears virtually no resemblance to that of Jude Law, who played him in the sadly underwhelming 2001 film Enemy at the Gates. (No criticism of Law; criticism of the script.) A vastly closer match (at the very least, in terms of appearance) would be Wes Chatham, of The Expanse.

Here’s Vasiliy Zaitsev’s Hero of the Soviet Union award citation.

General Chuikov and Commissar Gurov’s signatures appear in the “second line from the top” on the upper half of the second page.

The central text of the citation itself – visible in the bottom half of the document’s first page – appears below this image, in Cyrillic and with an English translation.

“За период с 10 октября по 17 декабря 1942 года в уличных боях за Сталинград снайпер Василий Зайцев уничтожил 225 немецких солдат и офицеров. Участвуя в оборонительных и наступательных боях, он ежедневно пополнял свой боевой счет. Непосредственно на переднем крае Зайцев обучал снайперскому делу бойцов и командиров. В результате умелой организации и личного примера Василий Зайцев подготовил 28 отличных снайперов.

“За период с 10 октября по 17 декабря 1942 года в уличных боях за Сталинград снайпер Василий Зайцев уничтожил 225 немецких солдат и офицеров. Участвуя в оборонительных и наступательных боях, он ежедневно пополнял свой боевой счет. Непосредственно на переднем крае Зайцев обучал снайперскому делу бойцов и командиров. В результате умелой организации и личного примера Василий Зайцев подготовил 28 отличных снайперов.

Его ученики-снайперы: П. Двояшкин уничтожил 78 немцев, Морозов – 66, Шайкин – 58, Куликов – 51 и др. Всеми снайперами 1047-го стрелкового полка уничтожено 1106 немцев. Велика заслуга снайпера В. Зайцева перед Родиной. Достоин присвоения высшей правительственной награды “Герой Советского Союза”.”

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

“During the period from October 10 to December 17, 1942, in street battles for Stalingrad, sniper Vasiliy Zaytsev destroyed 225 German soldiers and officers. Taking part in defensive and offensive battles, he replenished his combat account every day. Directly at the forefront, Zaytsev taught sniper fighters and commanders. As a result of skillful organization and personal example, Vasiliy Zaytsev trained 28 excellent snipers.

His pupils – snipers: P. Dvoyashkin killed 78 Germans, Morozov – 66, Shaykin – 58, Kulikov – 51 and others. All snipers of the 1047th rifle regiment destroyed 1106 Germans. The great merit of the sniper V. Zaytsev to the Motherland. Worthy of being awarded the highest government award “Hero of the Soviet Union”.

__________

Here’s the cover of Ballantine’s paperback edition of The Battle for Stalingrad. Published in October of 1968, the book features wrap-around cover art by Robert E. Schulz, which, typical of Schulz’s illustrations, is dramatic and directly representational, unlike that of the book’s (first) hardcover edition.

____________________

Here are a few other covers by Robert Schulz in the genres of science fiction, military history, and military fiction.

The Best of Barry N. Malzberg – January, 1976

Sands of Mars, by Arthur C. Clarke – June, 1959 (April, 1952)

I Robot, by Isaac Asimov – 1956

The Last Parallel, by Martin Russ – 1957 (1958)

HMS Ulysses, by Alistair MacLean – 1953

____________________

Here’s Hanson W. Baldwin’s introduction to General Chuikov’s book, which is fascinating in its detail and perspective, given that it was written in the early 1960s, during the (first ?!?) Cold War.

INTRODUCTION

by Hanson W. Baldwin

At Stalingrad, as Winston Churchill wrote, “the hinge of fate” turned.

Stalingrad and the campaign of which it was a part was a decisive battle of World War II. It was the high-water mark of German conquest; after January 31, 1943, when Field-Marshal Friedrich von Paulus surrendered what was left of the German 6th Army, the paths of glory for Hitler and his legions led only to the grave.

In late June, 1942, Stalingrad, strung along the west bank of the Volga for some thirty miles where the great river makes its sweeping loop to the west, was the third industrial city of the Soviet Union. The front then was far away. The Nazis had been halted at the gates of Moscow in November and December, 1941, and the war of Blitzkrieg had been turned into the war of attrition. Pearl Harbor had brought the United States, with all its immense potential, into the war, and in North Africa, despite Rommel’s victories, British armies still held the gateway to Egypt and the Suez Canal. Hitler faced the specter that even he dreaded – war on many fronts.

Yet the USSR was sorely hurt and German armies still held a 2,300-mile front deep within the Russian “motherland.” The Reich that was to last a thousand years mobilized new units and called on sixty-nine satellite divisions – Rumanian, Italian, Hungarian, Finnish, Spanish, Slovak – to bolster German strength for a gargantuan effort.

For the 1942 campaigns Hitler substituted economic for military goals. His eyes shifted from Moscow to the oil fields of the Caucasus. The Drang nach Osten (push to the East), which had lured the Kaiser, influenced his plans for the German armies.

The basic German objective in the great seven-months campaign, of which the battle for Stalingrad was a key part, was the oil of the Caucasus and penetration of that great mountain barrier. Russian armies in the Don bend – where the river looped far to the east within a few miles of the westward-looping Volga – were to be destroyed. Stalingrad was originally envisaged as a means to a more grandiose end; the Russians were to be deprived of its “production and transportation facilities” and traffic on the Volga was to be interrupted either by actual seizure of the city or by artillery fire. The city was not a key objective.

At the start of “Operation Blau” in late June, 1942, about 100 Axis divisions had been concentrated in Southern Russia opposite about 120 to 140 Soviet divisions. Army Group A was to drive deep into the Caucasus; Army Group B, of which the 6th Army was a part, was to clear the banks of the Don of all Soviet forces and hold the long northern flank of the great Caucasian salient, from Voronezh, the pivot point of the operation, through Stalingrad southward toward Rostov.

The huge German offensive had sweeping initial success; Russian forces were shattered, Voronezh fell, and the 6th Army drove eastward into the loop of the Don. Through the gateway of Rostov and across the Kerch strait, Army Group A drove deep into the Caucasus.

But late in July, 1942, Hitler, who fancied himself a master strategist and who handled every detail of military operations on the Russian front, shifted the schwerpunkt, or main weight of attack, northward from the Caucasus toward Stalingrad. Stalingrad gradually became an end in itself; Hitler came to realize that the city on the Volga dominated a key part of the exposed northern flank of the southern offensive. In General Franz Halder’s words he understood, too late, that “the fate of the Caucasus will be decided at Stalingrad.”

August, 1942, was a black month for Soviet Russia and for the Allies. In the West the Dieppe raid was repulsed bloodily. In the Caucasus German tanks captured the Maikop oil fields and the Nazi swastika flew on the Caucasus’ highest peak – 18,481 foot Mount Elborus. On August 23rd, after a 275-mile advance in some two months, Panzer Grenadiers of the German 6th Army reached the Volga on the northern outskirts of Stalingrad and the long trial’ by fire started.

The five-month battle in and around Stalingrad – the subject of this book – was only a part of a far vaster drama played across an immense stage of steppes and forests and mountains. As the southern campaign progressed, the vast spaces of the Russian land – which had defeated Napoleon – muffled the German blows. Army Groups A and B were engaged in divergent attacks, each with weak and insecure flanks, separated by some fifteen hundred miles of hostile “heartland.” Logistics, the problem of supply which can make or break the best-laid plans of any general, became more and more important the deeper the Germans drove into Russia. And as stiffening Soviet resistance, plus their own difficulties, slowed the German advance Hitler milked more and more troops away from the vital northern flank of the deep salient – the hinge of the whole operation from Voronezh to Kletskaya – to re-enforce Paulus’s 6th Army at Stalingrad. This flank, which held the key to the safety of the German forces at Stalingrad and in the Caucasus, was held by the Hungarian, Italian, and Rumanian armies with only slight German support, the weakest of the Axis forces in the most important area. And south of Stalingrad, almost to the communications bottleneck at Rostov, there was an open flank of hundreds of miles, patrolled for many weeks by only a single German motorized division. The front was, in truth, “fluid.”

Except at Stalingrad. In July and early August Stalingrad might have been easily captured, but the German schwerpunkt then was toward the Caucasus or was just shifting toward Stalingrad. From September on, as Paulus, ever obedient to Hitler’s orders, drove the steel fist of the 6th Army squarely against the city on the Volga, resistance stiffened. The German advantage of mobility was lost in the street fighting, and the battle of Stalingrad became a vicious, no-quarter struggle for every building, each street.

When the main German attack to seize the city started in mid-September, Paulus and his 6th Army, with the 4th Panzer Army on the southern flank, held with five corps (about twenty divisions in all) the forty-mile isthmus between the Don and the Volga. From eight to fourteen of the German divisions fought in the city and its suburbs. Paulus was opposed in Stalingrad by the 62nd (Siberian) Army, commanded by Lieutenant-General Vasili Chuikov (the author of this book), who originally commanded some five to eight divisions (subsequently re-enforced). Moscow created a special Stalingrad Front (equivalent to an Army Group) commanded by Andrey Yeremenko and elements of the 64th Soviet Army, astride the Volga, and the 57th Army faced the 6th Army outside Stalingrad and the German 4th Panzer Army south of the city.

These were the forces that asked no quarter and gave none in one of the bloodiest battles of modern times. Stalingrad, between September, 1942, and February, 1943, became a Verdun, a symbol to both sides; for Hitler it was an obsession. In its battered factories, from its cellars and sewers, from rooftops and smashed windows and piles of rubble, Paulus and Chuikov fought a battle to the death.

At first the Germans were on the offensive, inching forward yard by yard here, reaching the Volga there. Front lines were inextricably confused; there were few flanks, no rear; fighting was everywhere.

But by mid-November, with the Battle of El Alamein lost in Egypt, Paulus was almost through. On November 19th, when the iron blast of winter had hardened the steppes, some half-a-million Soviet troops and fifteen hundred tanks, concentrated on the flanks of the Don and Volga bends, struck. The first blows broke through the vulnerable northern flank held by Germany’s hapless allies, and by November 22nd, the Don Front (Rokossovski) and Yeremenko’s Stalingrad Front, with some seven Russian armies, had closed their pincers at Kalach on the Don bend, encircling in the isthmus between the Don and the Volga and in Stalingrad more than two hundred thousand soldiers of the German 6th Army, a few units of the 4th Panzer Army, elements of two Rumanian divisions, Luftwaffe units, a Croat regiment and some seventy thousand noncombatants, including Russian “Hiwis” (voluntary laborers who aided the Germans) and Russian prisoners. When the encirclement was complete the Germans in the Caucasus had pushed to within seventy-five miles of the Caspian Sea.

The Kessel, or encirclement, originally covered an area about the size of the state of Connecticut, not only the city of Stalingrad itself but large areas of frozen, wind-swept open steppe westward to the Don. Hitler called it “Fortress Stalingrad” and forbade any attempt at breakout; where the German soldier had set foot he must remain.

The rest is history – sanguinary, brutal history – the slow, and then the rapid, death of an army and of a city. An airlift was organized to supply Paulus on November 25th, and in the bitter winter weather of December, Manstein, possibly the ablest German commander of World War II, attempted to break through the Russian encirclement to relieve Stalingrad. He almost succeeded; his Panzers driving along the Kotelnikovski-Stalingrad railway reached to within thirty miles of the 6th Army’s outposts by December 21st, but Paulus, obedient to Hitler’s stand-fast orders, made no effort to break out. By Christmas Day all hope had gone; Manstein was in full retreat and the last days of agony of the 6th Army had started.

On January 31, 1943, a dazed and broken Paulus surrendered in the basement of the Univermag department store in what was left of Stalingrad. But Hitler was right in the long run, the 6th Army did not die in vain. Until the end of December Hitler had forbidden the withdrawal of Army Group A deep in the Caucasus, though the northern flank of the great salient on which its safety depended was in shreds. But in January, while the 6th Army died, Manstein – repulsed in his attempt to relieve Stalingrad – fought desperately and successfully to hold open the gateway to safety at Rostov, as Germany’s conquering legions in the Caucasus withdrew in a brilliant but precipitate retreat across the mouth of the Volga and the Kerch strait from the conquests they had so briefly held.

The 6th Army, ordered to fight to the death, undoubtedly diverted Russian divisions from concentrating against the Rostov gateway and prevented, by their sacrifice, an even greater Soviet triumph. Army Group A in the Caucasus escaped to fight again, and the war’s ultimate end was still two long years away.

The Battle of Stalingrad was even more important politically and psychologically than it was militarily. An entire German army was destroyed for the first time in World War II; of some 334,000 men, only about 93,000 survived to surrender (plus some Rumanians and 30,000 to 40,000 German noncombatants and Russian “auxiliaries” and civilians). The shock upon the German mind was terrific; the myth of invincibility had been forever broken. After the Battle of Moscow and the entry of the United States into the war the Germans had no hope of unconditional victory. After Stalingrad they had little hope of conditional victory, of a negotiated peace with Stalin.

Hitler at Stalingrad attempted to achieve unlimited aims with limited means; he became obsessed with his own infallibility. His lust for global power recoiled in blood and death from the ruins of Stalingrad; from then on, the German tide was on the ebb.

Soviet military history – like all Soviet history – hews to the party line: it does not hesitate to make black white; it sets out to prove a point, not to accumulate and relate the facts. Truth, in terms of dialectical materialism, is relative; it is what the party says it is.

These faults, which were even carried to such an extreme as to obliterate totally from the record the names of Russians who cast their lot with the West (such as Vlasov), were particularly pronounced under Stalin. But, since his death, the gradual “thaw” which has influenced Soviet life and mores has affected even the writing of military history.

The official Russian history of World War II, now being published – though still reticent in many areas – is refreshingly frank as compared to the polemical sketches of a decade ago. However, there have been relatively few book-length memoirs or authoritative personal accounts by Soviet wartime leaders; it was safer to be inconspicuous than to bring down the possible wrath of official displeasure by putting anything on the record.

In fact, the historian of the Russian front has found, until recently, very little grist for his mill; the German records are excellent but one-sided. Of the available Russian material, accounts published in military magazines were perhaps the best, though most of them were brief and devoid of details. A few official Soviet accounts, which had been written for official use only but which had fallen into U.S. hands, presented a somewhat less biased picture. A notable example of this kind of document, which deals with the battle for Stalingrad, is a study of the battle under the title Combat Experiences, published with the sponsorship of the Red Army’s general staff in the spring of 1943 for a restricted military audience. A translated copy of this document – which, unlike most publicly available Soviet history, admits mistakes and is relatively frank – is in the files of the Office of the Chief of Military History of the United States Army in Washington, D.C.

To these sparse sources this book by Marshal Chuikov is a very welcome and an important addition. During the battle Chuikov commanded the 62nd (Siberian) Army, which was directly responsible for Stalingrad’s defense; he might be called, in Western parlance, “the Rock of Stalingrad.” Chuikov is now, at writing, commander in chief of Soviet land forces, and his book makes it obvious that he pays obeisance to Premier Khrushchev.

As judged by Western military memoirs The Battle for Stalingrad appears episodic, fragmented, and far from complete. But by past Soviet standards it ranks high. It provides very considerable new insight into the battle in the city itself, and there are many surprising flashes of frankness. The memoir adds materially to our knowledge of a struggle which was the beginning of the road to ultimate Allied victory.

Occasional frank tributes to German combat effectiveness, open criticism of some Soviet commanders, admissions of tactical mistakes and of very heavy casualties, accounts of confusion and supply and medical deficiencies would all seem to attest to the essential validity of this account.

More than a thousand soldiers of the 13th Guards Infantry Division reached Stalingrad with no rifles. The Soviet system of political endorsement of military orders is described.

The narrative makes clear that Stalingrad was in truth a Rattenkrieg, or “war of the rats”; its horrible hardships and bitter fighting are implicit in Chuikov’s account, although the pitiless nature of the struggle and the atrocities on both sides that accompanied and followed the battle are glossed over.

Mother Volga was always at the back of the Russian defenders in the Stalingrad battle; it was at once comfort and agony. For all supplies had to be ferried somehow across this great river to the rubble heaps and cellars of Stalingrad, and the wounded had to be removed across the same water route. Chuikov’s description of some of the expedients resorted to during the period of major supply difficulties from November 12th to December 17th, before the river was frozen solid but while it was full of huge cakes of floating ice, provides a kind of thumbnail tribute to the strengths of the Russian soldier – the strength of mass, of unending dogged labor, of sweat and blood, of love for Mother Russia, of courage.

Chuikov contributes, too, specific details of battle orders issued by him and by other unit commanders, and he fills in gaps in the West’s knowledge of the Russian units that fought in the Stalingrad campaign. There are interesting and informative sections dealing with the contributions of Russian women, as soldiers and auxiliaries, to the defense of Stalingrad.

On the whole, The Battle for Stalingrad adds materially to the data on Stalingrad; indeed, it presents from the Russian point of view more detail of the battle in the city itself than any other volume in English.

The book, of course, does not entirely escape from the inevitable polemical fetters which handicap every Soviet historical work – despite the new liberalism. The author time and again pays sycophantic tribute to political commissar Khrushchev, who was the Communist Party representative at the Stalingrad Front headquarters east of the Volga, but who never once – as far as this book indicates – entered the shattered city of Stalingrad during the fighting. The real architects of the great Russian victory in the Stalingrad-Caucasus campaign – the then Generals Georgi Zhukov, Alexander Vasilievski, and Nikolai N. Voronov – receive no credit. Stalin is conspicuous by his absence. German losses and German troop strengths are exaggerated, and, despite frequent mention of heavy Russian casualties, the reader will search in vain for that rarest of all statistics: specific figures of Soviet casualties. And one will find no appreciation of the “big picture” or of the contribution to final victory of the United States or Great Britain.

Despite these weaknesses – inevitable in the Soviet literature of war until communism changes its stripes – this book is an addition to history, a chronology of a famous victory, and a study in command and tactics.

Despite the dialectical cant with which Moscow has tried, until recently, to cloak Soviet military concepts, all soldiers in all armies draw common lessons from the common heritage of war. Marshal Chuikov shows himself in his memoirs to be a perceptive and vigorous commander. And despite his Communist ideology, he sums up his experiences at Stalingrad – one of the world’s great battles – in terms often used at military schools everywhere:

1. Use historical examples, but don’t repeat them blindly.

2. Don’t “stand on your dignity”; listen to your subordinates and don’t encourage them to be “yes-men.”

3. Don’t cling blindly to regulations.

Stalingrad – its name now changed by one of those ironic twists of which Communist policy is so full to Volgograd – stands today restored, enlarged, a monument to disaster and to triumph, a symbol of man’s inhumanity to man, a site of awful carnage, of fierce patriotism and burning loyalties, a city which will forever live, like Troy, in the tears and legends of two peoples.

New York

__________

My other Battle-of-Stalingrad relate posts pertain to Russian-Jewish writer Vasiliy Grossman’s book The Years of War and his novel Life and Fate, serialized for BBC Radio, and adapted by Sergey Ursulyak as a 12-episode television mini-series produced in the Russian Federation, the latter available through Amazon Prime Video (19 5-star reviews). I watched every episode, and would entirely concur with the 5-star reviews. Given the novel’s size, complexity, number of characters, and especially the depth and profundity of Grossman’s writing and beliefs about human nature, freedom, and tyranny, Ursulyak did a magnificent job of adapting the story for television.

I think you’ll like it.

Information for Your Further Distraction…!!!

Craig, William, Enemy at The Gates – The Battle for Stalingrad, Ballantine Books, New York, N.Y., 1974

Hanson W. Baldwin…

…at Wikipedia

Hanson W. Baldwin Papers…

…at Inventory at Syracuse University

…at Archives at Yale

Battle of the Century (Сражение века – Srazhenie Veka) – Describes General Chuikov’s experiences during the Battle of Stalingrad (in Russian), at militera.lib.ru

End of the Third Reich (Конец третьего рейха – Konets Tretego Reykha) – Describes General Chuikov’s experiences during the last months of the war, ending with the Battle of Berlin (in Russian), at militera.lib.ru

Soviet tactic of “hugging the enemy” in contemporary battles, at Quora

Battle of Stalingrad…

…at Wikipedia

…at Brittanica.com

TIK History (“Filthy detailed and super-accurate” World War 2 documentaries”.) Much emphasis on the Eastern Front, but a wide variety of other topics are also covered.

Vasiliy Ivanovich Chuikov…

at WarHeroes.ru

…at Wikipedia

Vasiliy Grigorevich Zaytsev…

…at WarHeroes.ru

…at Wikipedia

Volgograd…

…at Wikipedia

209 – March 7, 2021