Being that I’m currently binge-watching Amazon Prime’s The Man In The High Castle (on Season Three just now) while holding off on season four of The Expanse ’til I’m done (aaaargh! – how much longer can I wait?!), I though it apropos to present Alexander Star’s perceptive and pithy essay about Philip K. Dick’s life and literary oeuvre, which was published in The New Republic in 1993.

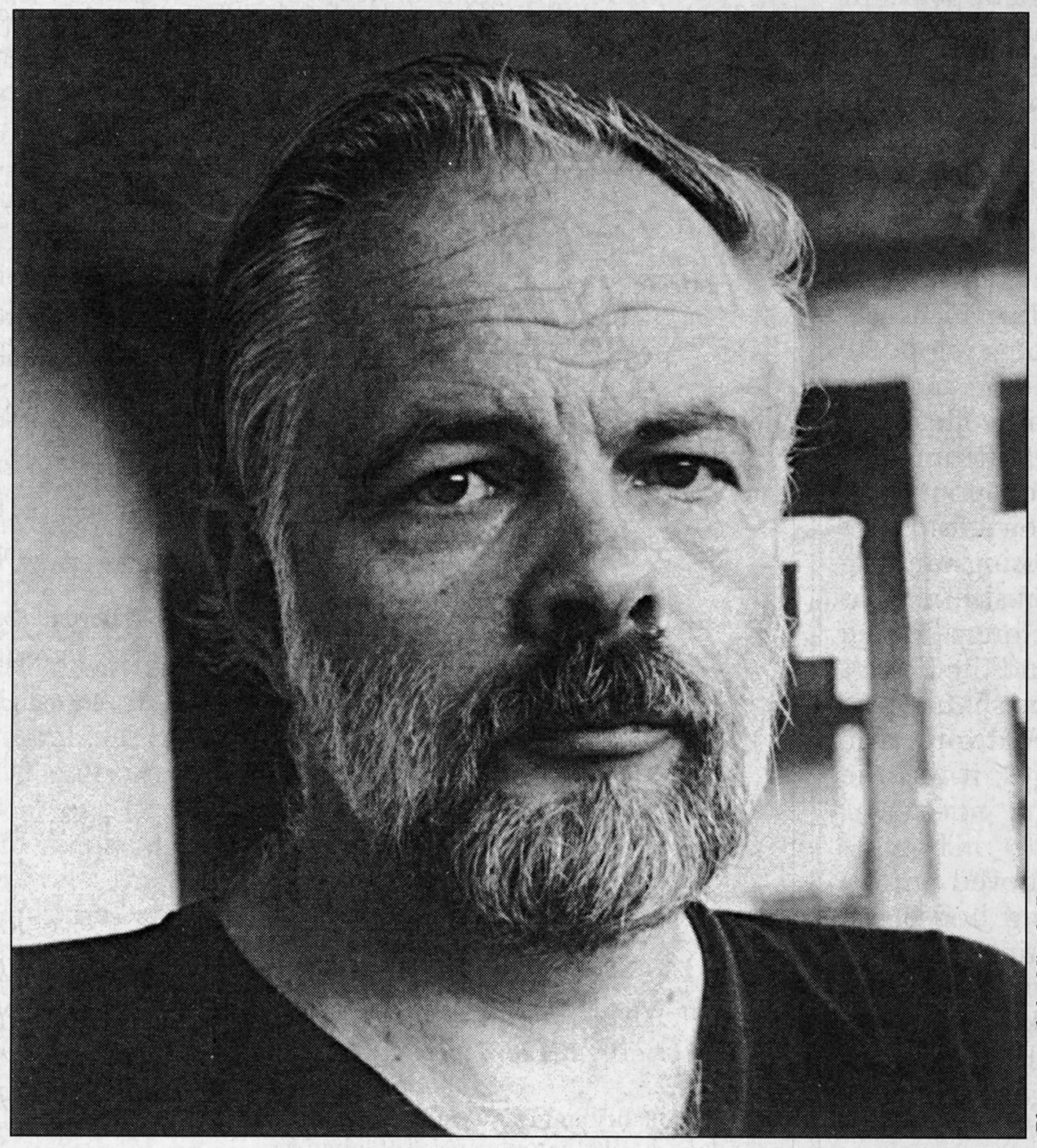

Alexander Star’s essay includes a portrait of PKD by former punk rock band manager (for the Germs) and actor & writer (for The Pee-Wee Herman Show) / script editor / author / essayist / photographer / jeweler (and more) Nicole Panter. (See photo below.)

Nicole Panter’s Flickr photostream also includes a superb 1978 color image (posted in 2008) of PKD, Nicole herself, K.W. Jeter and Gary Panter. Being that I’ve no idea whether the image is copyrighted or not, I’m not actually presenting it “here”, in this post. Rather, you can view it at Ms. Panter’s Photostream, here.

________________________________________

The God in the Trash

The fantastic life and oracular work of Philip K. Dick

The New Republic

December 6, 1993

(Photograph of Philip K. Dick by Nicole Panter)

(Photograph of Philip K. Dick by Nicole Panter)

________________________________________

Eye in the Sky by Philip K. Dick (Collier, 243 pp., $9 paper)

Time Out of Joint by Philip K. Dick (Carroll & Graf, 263 pp., $3.95 paper)

The Man in the High Castle by Philip K. Dick (Vintage, 259 pp., $10 paper)

The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch by Philip K. Dick (Vintage, 230 pp., $10 paper)

Ubik by Philip K. Dick (Vintage, 216 pp., $10 paper)

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. Dick (Ballantine, 216 pp., $4.95 paper)

A Scanner Darkly by Philip K. Dick (Vintage, 278 pp., $10 paper)

Valis by Philip K. Dick (Vintage, 256 pp., $10 paper)

The Collected Stories of Philip K. Dick (Citadel Press, 5 volumes, $12.95 each)

In Pursuit of Valis: Selections from the Exegesis edited by Lawrence Sutin (Underwood-Miller, 278 pp., $14.95 paper)

Divine Invasions: The Life of Philip K. Dick by Lawrence Sutin (Citadel Press, 352 pp., $12.95 paper)

On Philip K. Dick: 40 Articles from ‘Science-Fiction Studies’ edited by R.D. Mullen et al. (SF-TH Inc., 290 pp., $24.95, $14.95 paper)

I.

Eleven years after his removal to a Colorado graveyard, Philip K. Dick is among the busiest of American writers. New novels arrive regularly from the tomb; box office smashes (Total Recall) and Hollywood classics (Blade Runner) are spliced from his work; young writers of diverse persuasions sit raptly at his icy feet. A science fiction journeyman, ardent bohemian and restless observer of suburban life, Dick never discovered a place for himself while he lived. He was dismissed as a crackpot and hailed as a “visionary among charlatans”; and like most visionaries, he had a hard time finding a publisher. Today his published work could fill a small bookstore.

To enter a novel by Philip K. Dick is to enter a zone of disappearing worlds, nested hallucinations and impossible time-loops. This domain is inhabited by lonely repairmen, egotistical entrepreneurs and hapless housewives, and strewn with slant humor and menacing paradox. Although the books vary, their inspiration is always the same: they are governed by a passionate apprehension of appearances. Few writers have ever been so distrustful of the phenomenal world. Dick’s characters are driven to doubt their environment, and their environment is driven with an equal and opposite force to doubt them. There is always some primal error in Dick’s fictions, something “out of joint,” and the location of that error – inside the individual or outside the individual – can never be decided upon. Dick systematically blurs the boundaries between mind and matter, between storms in the psyche and crises of the atmosphere. The coiling search to set things right is doubled and redoubled and doubled again. Dick never met a story that ended or a regression that was finite.

Although he is still pigeonholed as a writer of science fiction, Dick had little respect for the prestige of science, and even less for the dignity of fiction, to which it must be said he contributed very little. His interest in hard and applied science was minimal, extending not far beyond a persistent (and unhappy) acquaintance with the details of automobile repair. His maddeningly profuse plots make a mockery of the notion that the novel can be a stable and self-sustaining work of art. And yet, all this notwithstanding, Dick’s novels demand attention. They intrude extreme experiences into everyday scenarios with compassion, humor and poise. He is both lucid and strange, practical and paranoid. (“By their fruits ye shall know them, and their fruits are that they communicate by radio.”) There is nothing merely willful or notional in the bizarre aspects of Dick’s work.

As an experimental writer of the 1950s and ‘60s, Dick belongs in the company of William Burroughs, J.G. Ballard and Thomas Pynchon. His novels recall Burroughs’s pitiless cycles of addiction and schizophrenia and Ballard’s eroticized landscapes of celebrity and death. What he lacks of Ballard’s unnerving coolness and Burroughs’s deadpan swagger, he makes up for with a compassion that is quite alien to them. His most esoteric dismantlings of reality still insist on the need for human empathy; and they do so with an alertness to the serious obstacles that empathy must sometimes encounter. Like Burroughs, his clipped prose wittily recycles the cliches of advertising lingo (“Emigrate or Degenerate: The Choice is Yours”) and pulp writing (“You’re a successful man, Mr. Poole. But, Mr. Poole, you’re not a man. You’re an electric ant”). Sometimes it reaches a higher level of eloquence. In his later years, as he came to believe that the revelations of a medieval rabbi were reaching him through occult channels, Dick’s sanity was open to question. But throughout his career he wrote with qualities that are rare in a science fiction writer, or in any writer at all. These included a sure feel for the detritus and debris, the obsolescent object-world, of postwar suburbia; a sharp historical wit; and a searching moral subtlety and concern.

II.

A heavy man with an absent smile and an intent gaze, Philip Dick typed 120 words a minute even when he wasn’t on speed, drank prodigious quantities of scotch and completed five marriages and over fifty novels before the pills and the liquor conspired to kill him at 54. His busy life has been ably narrated by Lawrence Sutin in his biography, Divine Invasions, which appeared a few years ago. Born in 1928, Dick witnessed the Depression from inside a broken home. His father, an employee of the Department of Agriculture, left the family in 1931 and went on to host a radio show in Los Angeles called “This is Your Government.” Dick grew up with his mother on the fringes of Berkeley’s fledgling bohemia. A troubled student, he was often “hypochondriacal about his mental condition,” as one of his wives later put it. And like many troubled boys of the time, he became a voracious reader of the science fiction pulp magazines that were then at their peak. In Confessions of a Crap Artist, a novel written in 1959, he wryly portrayed himself as an awkward kid spouting oddball ideas from Popular Mechanics and adventure stores: “Even to look at me you’d recognize that my main energies are in the mind.”

Dick evidently had few friends until he went to work at a record store in Berkeley, where he acquired an encyclopedic knowledge of classical music and the friendship of customers and colleagues. “Art Music” was also a site of romance. The employees, university dropouts with time to spare, courted their customers with cunning; after impressing one frequent browser with his musical expertise, Dick married her. Not long after the wedding they quarreled, and the bride’s brother threatened to smash his precious record collection. A divorce followed; of his five marriages, it was the shortest.

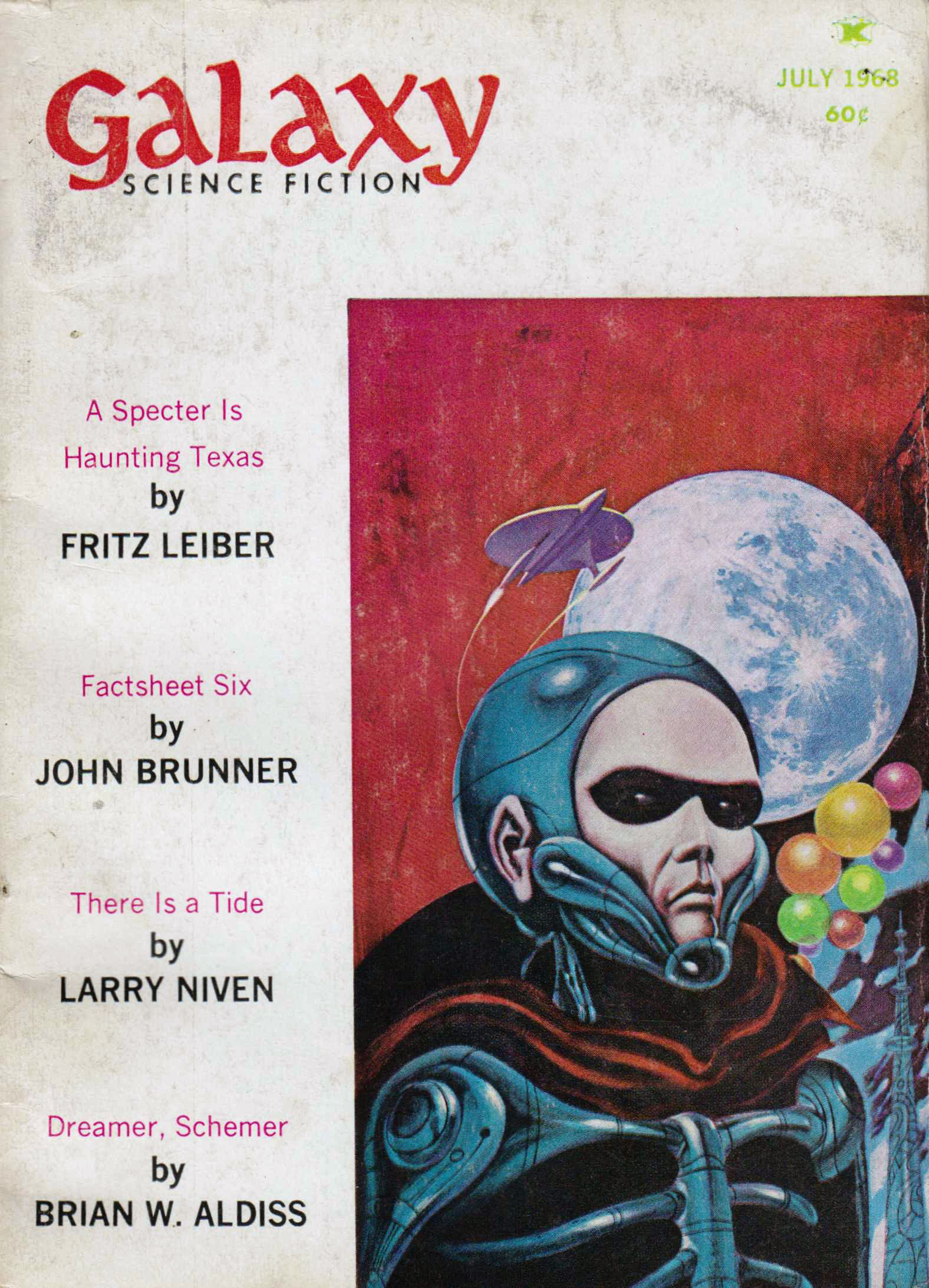

In 1947, Dick moved into a Berkeley rooming house, living for a short time with the poet Robert Duncan. After one unhappy term at Berkeley in 1949, he married again and settled down to a writing career, publishing his first science fiction stories in 1952. Dick entered the market at a time when the genre was in flux. Like the big bands, the great pulp magazines of the ‘30s declined after the war. They were replaced by a flood of cheap paperbacks, and the leading format for science fiction became the “double paperback” published by Ace Books, two novels together in one binding with a different lurid cover illustration on each side. Throughout the ‘50s Dick worked closely with Ace’s top editor, Don Wollheim. Typing from morning to night, he cranked out large quantities of prose, and turned himself into a typically prolific and typically uneven writer of the genre.

Dick was not unsuccessful at this: his novel Solar Lottery, published in 1955, sold 300,000 copies, and he became one of the first clients of the powerful agent Scott Meredith. Still, it was not a writer’s life; royalties were meager and manuscripts were altered at will to ensure the proper amount of extraterrestrial warfare and gee-whiz gadgetry. (The Zap Gun was written because Wollheim insisted on publishing a book with that title.) As he read widely Dick’s frustrations with science fiction grew, and his discontent became apparent.

Throughout his career Dick longed for a wider audience, and sought to escape the science fiction ghetto. He envied writers such as Ursula Le Guin, who acquired a serious reputation and was even published in The New Yorker. His readers, he complained, were “trolls and wackos.” In the ‘50s and early ‘60s, he wrote a series of non-science fiction novels, all of which were rejected by publishers at the time. These books were mainly somber tales of thwarted love in northern California, peopled with cranky record salesmen and bitter couples and narrated in a glumly painstaking fashion. On the whole, their vision of domestic life is an unhappy one. In Confessions of a Crap Artist, an accumulation of errant jealousies and petty insults leads to illness and insanity. The novel ridicules the newly formed UFO cults of Marin County, though years later Dick reflected that the cults “didn’t seem as crazy to me now …”

Rebuffed by “mainstream” publishers, Dick abandoned his realist writings in 1963. By then he had discovered a different way out of the Ace formula: he would transform the genre of science fiction from within. Concerned with psychic dislocation, and its moral and philosophical consequences, he began to ignore the expectations of his editors. In particular, he disregarded the most honored conventions of “hard S.F.,” that science fiction should be rigorously “extrapolative” of hard science, and that it should be “prophetic” of plausible futures.

By the late ‘50s, these conventions had a long and venerable history. When Hugo Gernsback started his magazine Amazing Stories in 1926, initiating modern science fiction, he hired Thomas Edison’s son-in-law as a fact checker. In its heyday, John W. Campbell Jr.’s Astounding Stories [sic] insisted that writers postulate one outlandish circumstance – the “what if?” clause – and rigorously follow the laws of science from there. After World War II these conventions loosened, as the optimistic narrative of invention and discovery was tempered by dystopian broodings and doubts about the authority and integrity of science. But the most important figures, Asimov, Heinlen, Bradbury, remained faithful to the Campbellian requirements of scientific accuracy and plausible prophecy. As Asimov put it, “In my stories I always suppose a sane world.”

Philip Dick’s fictional worlds have a great many attributes, but sanity is not among them. Campbell, the monarch of postwar science fiction, refused to publish his stories because they were “too neurotic.” In his preoccupation with abnormal psychology, collective delusions and implanted memories, Dick in part followed the path of irregular science fiction writers of the ‘50s such as A.E. van Vogt and Theodore Sturgeon. Yet he ranged further in his subversions. Dick continued to rely on the ready-made materials of science fiction, the pulp prose, the planetary conflicts, the “psionic” powers of “precogs” (who read the future) and “telepaths” (who read minds); but he employed these materials to his own extravagant ends.

Dick’s novels of the late ‘50s were littered with intellectual debris of the period: the existential psychoanalysis of Ludwig Binswanger, popularized in America by Rollo May; the cybernetics of Norbert Weiner [sic] and the game theory of John von Neumann; gestalt psychology and Carl Jung; Tibetan Buddhism and the I Ching. Eye in the Sky (1957) amusingly presents a nation given over to ostentatious piety and soulless technocracy. Its engineers stabilize “reservoirs of grace” while “consulting semanticians” secure communication lines with God and IBM computers tabulate credits toward salvation. (The satire of religious fundamentalism worried Dick’s editors at Ace, who changed a central character into a Muslim to avoid offending readers.)

Time Out of Joint, which appeared in 1959, departed even further from the norms of science fiction. Its first hundred pages unfold a slow-paced story set in a small west coast town. Evidence that something is “out of joint” gradually amasses, until the startling scene when a soft-drink stand vanishes into a strip of paper labeled “SOFT-DRINK STAND” and the entire community is revealed to be a Potemkin village; it is, in fact, an artificial replica of the ‘50s constructed in 1994 to salve the nerves of the protagonist, whose sanity is essential to national security. In 1959 Dick was already proposing that the ‘50s themselves were a kind of pacifying fantasy available for the nostalgia of future generations. Where traditional science fiction stirred anxieties about the future, Dick deftly introduced his uncertainties into the present and recent past. Despite the concluding narrative fireworks, Ace refused to publish Time Out of Joint, and Doubleday brought it out instead as a “novel of menace.”

Dick’s biggest literary advance came in 1962, when he published The Man in the High Castle. This study of an alternate universe in which the Axis won the Second World War was entirely devoid of the usual sci-fi devices. (“No science in it,” a character observes. “Nor set in future.”) Mr. Tagomi, a Japanese bureaucrat and connoisseur of American antiques, is one of Dick’s most sympathetic characters. Repelled by international intrigue and devoted to the occult beauty of old bottle caps and cheap jewelry, he resists Nazi brutality with a fragile but steady will. Alter Bormann dies, a power struggle breaks out among the remaining Nazi leaders (Hitler has long since entered a sanitarium) and Tagomi unhappily plays one faction off against another, aware that they are all unspeakably evil. Ingeniously, the book contains its own counterfiction: in this America divided into German and Japanese zones, rumors spread of an incendiary novel speculating that the allies actually won the war. The narrative adroitly maneuvers back and forth between these two competing accounts of what is real. The Man in the High Castle was Dick’s most assured and subtle work, and he hoped it would win him a wider audience. He was chagrined when reviewers treated it as just another thriller. Ironically, it was the science fiction community that celebrated the book, bestowing the Hugo Award on it in 1963.

Fueled by marital troubles, esoteric visions and an epic diet of speed and scotch, Dick composed eleven novels in a hectic two-year period. The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch (1964) and Ubik, written in 1966, are his ‘60s classics, his wildest experiments in the manufacture and management of chaos. These are not Dick’s most accessible or likeable books, but they are his tours de force. (Both are among the dozen titles by Dick that Vintage Books has happily reissued over the past three years.) The time-loops and the Conspiracies, the conflicts between frail human subjects and large unsettling forces, the disorientations of perspective: all of these deuces are brought to new levels of complexity and compression.

In 1963, Philip Dick experienced the first of a number of “visions” that were to augment and to anguish his life. Depressed by a failing marriage and troubled by memories of his lather’s wartime gas mask, Dick reported that he saw “a vast visage of evil” in the sky. It had “empty slots for eyes, metal and cruel, and worst of all, it was god.” Out of this emerged the demiurgic figure of Palmer Eldritch in The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, an interstellar drug lord luring his customers and competitors into a “negative trinity” of “alienation, binned reality and despair.” Eldrilch’s powers are not absolute, but they are sufficient to rob other characters of confidence in their reality and in themselves. “We see into his eyes,” they fret, and we see out of his eyes.” In a typical conundrum, the protagonist, Leo Bulero, finds himself stranded in a blurred landscape, a “plain of dead things,” unable to know whether he is still in the grip of one of Eldritch’s hallucinations or whether he has returned to his original “reality.” He meets two men, shakes their hands and watches his lingers slip through theirs. He would assume that they are phantasms but they assume, just as reasonably, that he is a phantasm; and he concedes that they might be right. In the realm of the “irreal,” as Dick called it, to doubt the solidity of one’s surroundings is to doubt the solidity of oneself.

In Palmer Eldritch Dick perfected one of his “irreal” themes, the nested hallucination. In Ubik he perfected another, the experience of entropy, the onset of “decay, deterioration and destruction.” Imprisoned in a purgatorial “half-life,” the paralyzed characters of Ubik witness the spread of a cataclysmic force, a mass “reversion of matter” that causes objects lo revert to prior forms of themselves: televisions become radios, spray cans turn into jars of ointment. They struggle with their “obsessive fears that the entire world is turning into clotted milk” and “worn-out tape recorders,” that “all the cigarettes in the world are stale.” Stranded in his apartment, the central character resignedly watches his sleek, modern elevator become a creaky and dangerous relic. Ubik is a comedy of enforced obsolescence; the most familiar things acquire an unruly resonance as they confront their own historicity.

These two novels established Dick’s reputation as a master of experimental science fiction. Ubik inspired his election in Europe to the College du Pataphysique, a kind of Academie Francaise for Dadaists, and John Lennon expressed an interest in producing a film of Palmer Eldritch. “New wave” science fiction writers of the late ‘60s, led by Harlan Ellison, regarded him as a godfather. But Dick, as usual, received few financial rewards. The middle-aged pataphysician found himself living on welfare in a “run down, rubble-filled” house in Santa Venetia, a notorious crash-pad for dealers and runaways.

Squabbling with girlfriends, fearing the FBI and the IRS, Dick succumbed to serious bouts of paranoia and unease. (His paranoia was not entirely without foundation: in 1957 the CIA had in fact intercepted a letter that he had sent to a Soviet physicist. Fortunately he never knew of the Department of Health, Education and Welfare’s intention to compile a bibliography of drug-related science fiction.) In 1971 Dick’s stability declined further when someone broke into his home and looted his papers. He devoted countless hours of speculation to the identity of the burglars. It was his own private Watergate. At various times he suspected the FBI, the Black Panthers, a gang of local drug dealers, right-wing militiamen and himself. He retrieved one tentative lesson from the debacle: “At least I’m not paranoid.”

Dick’s writing of this period trembles with fear of a totalitarian “betrayal state” of advanced surveillance and narcotic intrigue. His novels envisage a burned-out post-’60s nation headed into a dark age of police repression and entertainment-enforced normality. In Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said (1974), the authorities deploy an arsenal of bugs, sensors, minicams and tattoos to solve the mystery of a man who thinks that he is a television talk show host even though no one has heard of him. A Scanner Darkly (1977) sympathetically observes the unraveling of Bob Arctor, an undercover cop in a Los Angeles police state where “straights” and addicts inhabit segregated areas and where access to shopping malls is restricted to those with the correct credit cards. Arctor slowly becomes unhinged as he is forced to narc on himself. Witnessing his friends’ fuzzy chatter (“Bob, you know something … I used to be the same age as everyone else”) and acute distress, he worries that “the same murk covers me.” Eventually it does; his brain splits into two distinct identities, his thinking comes to a halt and he becomes dead to the world: “His circuits welded shut.” With its well-scored drug talk and its terrible portrait of a mind becoming opaque to itself, A Scanner Darkly is Dick’s funniest novel, and his most affecting.

In 1972, striving to escape the druggy clutter, the spreading “murk,” of his life, Dick traveled to Vancouver, where he gave a speech to an annual convention of science fiction writers. In his lecture, “The Android and the Human,” Dick fashioned a kind of homespun anarchism, honoring young people of the ‘60s for their “sheer perverse malice,” their willingness to defy power, to “build improved electronic gadgets in your garage that’ll outwit the gadgets used by the authorities.” Eschewing the dogmas of the New Left, he warned that all systems of explanation tend toward overdetermination, toward paranoia. Paranoia, for Dick, was a temptation and a trap. He feared conspiracies, and he feared the debilitating consequences of his fears. And so, he advised, one “should be content” with the fleeting and the marginal, the “mysterious, the meaningless, the contradictory, the hostile and, most of all, the unexplainably warm and giving.” This sudden, self-justifying affection, which Dick also referred to as “caritas” and as “empathy,” was the only guarantee of the “human.”

Having diagnosed the breakdown of society in his speech, Dick suffered a breakdown of his own and checked into a Vancouver clinic run on brutal Synanon-style principles of rehabilitation. He was appalled by the clinic’s ruthless assault on its patients and their personalities, but his worst pill-popping days were through. Lured by a college professor who admired his work, he returned to California and moved into a “jail-like, full-security” apartment complex in Orange County. He married again and began to clean up his life, even writing to President Nixon and offering his assistance in the war against drugs.

But a complacent Orange County serenity was not at hand. In March 1974 Dick underwent a series of visions that astonished and thrilled and hounded him for the rest of his life. An onslaught of otherworldly insight and illumination seemed to press down on him for weeks. (“Once God started talking … he never seemed to stop. I don’t think they report that in the Bible.”) The elements of this experience, which he returned to obsessively in his writing, were many: flickering sequences of abstract color, three-eyed “invaders,” Latin and Russian texts, visions of a “Black Iron Prison,” messages that the Roman Empire never died, “hideous words” spoken out of an unplugged radio, a beam of pink light conveying knowledge.

When it was over, he believed that he had received confirmation that the universe was indeed the “cardboard fake” that he had long portrayed it to be. As in gnostic myth, the world of appearances was an “iron prison” under the sway of a defective deity; illumination was available only from outside the prison, from a pure source of knowledge that Dick referred to as a ‘Vast Active Living Intelligence System” (VALIS). For the remaining eight years of his life he filled notebook after notebook with an “Exegesis” of these peculiar days, constructing a gnostic cosmology involving “a double exposure of two realities superimposed.” But Dick was never satisfied with his speculations. In the Exegesis and in his novel Valis (1981), he wrestled with himself, asking over and over whether his revelations were real, and if they were not, what had triggered them. (Radio signals from the future? Water-soluble vitamins? A stroke?)

Dick observed in 1978 that “my life … is exactly like the plot of any one of ten of my novels or stories.” After systematically dislocating the reality-principles of his readers, he came to find his own relation to reality increasingly unsure. He combed T.V. ads and record albums for signs of VALIS, the hidden god. Dick left his last wife in 1976 and moved back north to Sonoma, where he cruised the local asylum for dates and wrote The Transmigration of Timothy Archer (1982), a troubled memorial to his friend James Pike. (Pike, the former Episcopalian bishop of California, had vanished in the Jordanian desert looking for Jesus, leaving behind two bottles of warm Coke and a road map.) Meanwhile the Exegesis became a sprawling spiritual diary, by turns ordinary and extraordinary, filled with philosophical disputation, personal reminiscence and analysis of his previous work.

In the early ‘80s Dick’s hopes for renown revived, as younger writers arrived at his doorstep, royalties increased and German, French and Japanese editions of his work proliferated. Back in the early ‘70s he had optioned his 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? to Hollywood; by 1980 the producers of the film promised that it would be the next Star Wars. (Dick hoped that Victoria Principal would have a starring role.) In fact, Blade Runner was a commercial disappointment in its initial release. But Dick never knew of its early unsuccess. In March 1982, he died of a stroke after proudly attending an advance screening of the movie.

Despite the greater comfort and recognition in his last years, Dick maintained his restless work on the Exegesis, ever lamenting the failure of his visions to repeat themselves, their maddening resistance to explanation. Later passages of the Exegesis express his mingled resignation, devotion and ingenuity: “My attempt to know (VALIS) is a failure qua explanation … Emotionally, this is useless. But epistemologically it is priceless. I am a unique pioneer … who is hopelessly lost. & the fact that no one yet can help me is of extraordinary significance!” Like one of his own perplexed characters, strung out between parallel worlds, Dick never solved the puzzles that rattled him. “They ought to make it a binding clause that if you find God you get to keep him,” he wrote sadly in Valis. “… Finding God (if indeed he did find God) became, ultimately, a bummer, a constantly diminishing supply of joy, sinking lower and lower like the contents of a bag of uppers. Who deals God?”

III.

In the years since his death, Philip Dick has attracted a small army of interpreters. He has been seen as a prophet of “hyperreality”; as a beleaguered and heroic humanist, championing “moral sanity” as his mind suffered; and as a gnostic visionary of the suburbs. Marxist critics and theorists of postmodernism have busily sifted through his work, investigating its debased commodities and corporate conspiracies, its cold war fears and its elevation of paranoia into principle. Dick’s fiction, in the view of the critic Scott Durham, is nothing less than a full-blown “theology of late capitalism” that “reflects on the psychic strains of the transition to postindustrial capitalism.” According to Jean Baudrillard, one of Dick’s many French fans, it is “a total simulation without origin, past or future.”

Dick himself, interestingly enough, was alternately gratified, amused and alarmed by the attention that modish critics gave to his work. When a delegation of French authorities visited him in Orange County to discuss his notions of “irrealism,” he offered them an exposition of his views, but as soon as they left he telephoned the FBI and warned that there was a gang of subversives in the neighborhood. (Dick’s politics were never especially coherent; he nearly dedicated A Scanner Darkly to Nixon’s Attorney General Richard Kleindienst, but in the Exegesis he treats Nixon’s resignation as a providential event in sacred history.) The Marxist and postmodern readings of Dick’s work are often informative; his novels do have more than their share of simulacra and spectacles, fractured identities and postindustrial proletariats. But these readings do not do justice either to his insistence on compassion as a stabilizing force or to his earnest search for an “absolute reality.” Their anatomy of “irrealism” is incomplete.

What, then, does this “irrealism” consist of? In the Exegesis, Dick confided that his writing had a single overriding theme: it indicted “the universe as a forgery (& our memories also).” In book after book, Dick portrayed the onset of doubt, of an elemental estrangement from reality. The perceived defect in the substance of the world is traced back to a variety of sources – atomic catastrophes and potent drugs, dangerous gods and political conspiracies, schizophrenic derangement and paranoid insecurity. But the origin doesn’t really matter; it is the experience of “irreality” that interested him most. As his characters confront exasperating hallucinations and intersecting time-sequences, they respond with a typical blend of desperate speculation, cautious empathy and brittle humor. (“God is responsible for everything, but it’s hard to get him to admit it.”)

The most recurrent anxiety in Dick’s fiction is that beneath the surface of appearances there is nothing except crude building materials: struts, wire, floor joists, rotten boards. This anxiety was suited to its times. The postwar heyday of science fiction coincided with a nationwide accumulation of raw materials; the United States became a Popular Mechanics Utopia. There was plenty of tin and wire and aluminum to go around, and there were plenty of young inventors prepared to devise ingenious contraptions in their garages. More than any other science fiction writer, Dick turned these innocuous materials into the stuff of nightmare. What if the paste and wire and tinfoil substratum of the built environment was also the substratum of our own bodies and minds? Such a possibility arises in one Dick novel after another: that the world is made of “wires and staves and foam-rubber padding,” that a man is a “skeleton wired together … with bones connected with copper wire … artificial organs of plastic and stainless steel … the voice taped.”

Indeed, you never know when one of Dick’s full-bodied characters might become a creaky automaton, no longer capable of empathy, love or spontaneity. Sometimes the transposition is metaphorical: “Her heart … was an empty kitchen: floor tile and water pipes and a drainboard with pale scrubbed surfaces, and one abandoned glass on the edge of the sink that nobody cared about.” Often it is deadly literal. In a harrowing passage of A Scanner Darkly, Dick compares an addict to a machine, programmed to find the next score. A junkie is a “closed loop of tape” with a “brain of twisted wire”; his voice is “the music you hear on a clock-radio … it is only there to make you do something … He, a machine, will turn you into his machine.”

In many of Dick’s early novels, these distortions of perspective are attributed to paranoia. His characters fear conspiracies and plots, preordained worlds where “there are no genuine strangers.” They also fear ordinary appliances and fixtures, dreading that “everything has a life of its own, vicious and hateful.” Things, appliances, entire houses suddenly come alive, bristling with menace. In later novels, the focus shifts to schizophrenia. Dick’s interest in abnormal psychology led him to the work of

Ludwig Binswanger, a Swiss psychoanalyst who believed that schizophrenia involved a disturbance in the patient’s orientation toward time. In his famous paper, “The Case of Ellen West,” Binswanger described the “tomb world” that his subject seemed to inhabit, a realm of “moldering and withering” in which time no longer moved forward and West felt like “a nothing, a timid earthworm smitten by the curse surrounded by black night.”

For Dick, the tomb world connoted a kind of interior entropy, a sentiment that the world and oneself are inexorably “moving toward the ash heap.” The process of decline is all-embracing: people, places, things, time and space themselves all seem caught in a great storm of regression. Terrifying visions of the tomb world recur throughout Dick’s novels of the late ‘50s and ‘60s. Tagomi, the sympathetic aesthete-bureaucrat of The Man in the High Castle, recoils from the presence of evil and likens human beings to “blind moles, creeping through the soil, feeling with our snouts. We know nothing.” In Martian Time-Slip (1964), the autistic child Manfred intuits a grotesque future of ashen limbs and dust-covered rubble. In Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? a radiation-damaged truck driver lives amidst global scarcity and barren silence. Ubik is his greatest distillation of the theme; in a film scenario for the novel, Dick brilliantly proposed to embed this decay in the movie itself, using older film stocks and directing techniques as the story progressed.

Dick’s alterations of ordinary reality, his tomb worlds and time-loops, never seem like conjuring tricks because he is able to establish the tangibility and the immediacy of the worlds that he disrupts. In Time Out of Joint, the bitter couple-swapping and boredom of ‘50s suburbia are nimbly detailed. Every potato peel and pinup photo is fully observed before the arrival of “leaks in our reality.” As the town begins to flicker in and out of view, Dick hauntingly presents the edges of his pseudo-environment: Main Street trailing off into a half-glow of empty shopping strips and gas stations, the bus station queues that don’t move, the strange airplanes that signal overhead.

Setting the immediate and the “irreal” into a precarious balance, Dick presented litanies of destruction, detailed inventories of objects that are named only as they vanish. In Time Out of Joint, we see “the soft-drink stand go out of existence, along with the counter man, the cash register, the big dispenser of orange drink, the taps for Coke and root beer, the ice-chests of bottles, the hot dog boiler, the jars of mustard, the shelves of cones, the row of heavy round metal lids under which were the different ice creams.” In Eye in the Sky, the survivors of a nuclear accident find themselves trapped in each others’ hallucinations. One member of the group is a fastidious Victorian moralist whose mind is a sexless place of soap factories and shrubbery. (For her, Freud believed in a basic urge to create cultural masterpieces, and worried that this impulse might be sublimated into sexual desire.) As she recoils from the polluted objects of the world, she wills their destruction. “Cheese, doorknobs, toothbrushes,” she calls out, and they all vanish. Her dismal roll call continues, and the entire planet begins to disappear.

Dick’s narrative method, here and elsewhere, is to furnish the world as he dismantles it. On a political level, this operation encapsulates the nuclear anxieties of the ‘50s. The artifacts of everyday life take on an extra poignancy, and a heightened presence, under the conditions of their own possible destruction. Indeed, only the specter of total incineration can make the sprawling banality of the California suburbs into something precious. But these vanishing things are also vulnerable to other, less apocalyptic dangers. In the degraded landscape of postwar consumerism, commodities are obsolescent and bear the seeds of their own demise. Dick sifts through the trash, the old magazines and the soiled wrappers; it is only a matter of time, he suggests, before the suburbs are swallowed by their own landfills. On an occult level, Dick’s negations suggest something very different. Just as the mind can make the world, he implies, so it can unmake it. In a reversal of Adam’s naming of the animals, the bestowal of names robs things of their materiality, it causes them to vanish. The danger, of course, is that you might not be the one with the power to name names. You might be on the list.

Dick’s fallen worlds are not, to put it mildly, happy places. And yet they are at least partially redeemed by fleeting glimpses of a hidden god. ‘Trash” and divinity, Dick believed, were intimately linked. In an Exegesis entry, he wrote: “Premise: things are inside out … Therefore the right place to look for the almighty is, e.g., in the trash in the alley.” A “concealed god,” he added in Valis, takes on “the likeness of sticks and trees and beer cans in gutters”; he “presumes to be … debris no longer noticed” so that he can “literally ambush reality, and us as well.” Dick did not regard the artifacts of industrial civilization as indices of man’s alienation from the divine. God’s disavowal of the world was both older and deeper. Carrying on a distinctly American visionary tradition, Dick proposed that God preferred industrial waste to holy sanctuaries. In its spiritualization of the coarse and the vulgar, Dick’s demotic gnosticism unexpectedly echoes Emerson, or Whitman, or even Melville. He sought a kind of urban sublime, looking for shards of divinity in piles of junk.

Dick’s spiritual beliefs were highly variable, but his ethical code was not. What becomes of love and loyalty, he asked, in a deceit-ridden world, in which all surfaces are suspect and all foundations can be unforged? Dick’s concise, somewhat saccharine and still moving answer was that empathy is the only ground for morality. The existence of the “other” is a sufficient reason for helping the other. The problem is that “we don’t have an ideal world where morality is easy because cognition is easy.” The substitution of circuity for nerve tissue can murder the possibility of empathy. Still, Dick insists that empathy is the only means to retain one’s humanity in a world that is “metal and cruel”. Many of his most memorable characters – Tagomi in High Castle, Leo Bulero in Palmer Edritch – grope towards an identification with others in defiance of their hostile and unyielding circumstances. Dick’s elevation of empathy is not a way to make morality easy; he was allergic to New Age bromides and to psychobabble of any kind. In the company of paste-and-wire executives and mechanical sweethearts, empathy is always a challenge.

Dick explored the problem of decency in a dead world most forcefully in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Rick Deckard is a bounty-hunter, paid to track down and destroy a party of androids that has infiltrated the planet. Deckard employs an “empathy” test that records his subjects’ responses to unpalatable thoughts of cruelty and death; the test can distinguish between androids and their identical-looking human counterparts. The typical Dickian twist comes when Deckard, unlike one of his partners, begins to empathize with the androids that he kills. Does this mean that he might be an android himself, or does his powerful feeling of empathy confirm precisely that he is human? Deckard investigates incidents of empathy with the care of an experiences detective, but he cannot take anything for granted. The special horror of the work is that a sudden “flattening of affect” might occur at any time, to others or to himself. The practice of empathy is fragile, uncertain and imperative.

IV.

Science fiction is a dangerous profession. Its practitioners have often mistaken themselves for prophets. L. Ron Hubbard began as a novelist, and his preliminary draft of Dianetics appeared originally in the pages of Campbell’s Astounding Science Fiction. Dick, too, was often unable to distinguish his writings from reality (“All I know today that I didn’t know when I wrote UBIK is that VBIK isn’t fiction”). But he never regarded himself as a priest or a propagandist. He worked out no system of spiritual evolution, no fourteen-point program for cosmic harmony. In his later work he diligently recorded his own struggle to cope with disquieting experiences and difficult losses. He held strange views, but he held them provisionally, and with a healthy measure of doubt. In his mystical writings, Dick was not trying to convert others, he was trying to comprehend himself. (Lawrence Sutin has produced a fascinating selection from the Exegesis, but it is unlikely that Dick ever intended these writings to be published.)

Dick’s double compulsion to assemble and to disassemble fictional worlds might seem merely strange, the product of a fertile and eccentric mind. Yet both tendencies also inform the history of fiction itself. The traditional novel invents a solid material setting; it displays all the metronomes, mantle pieces and ledgers of middle-class life. Yet it also investigates the social world with a stringent and destabilizing skepticism, questioning the correspondence of reality and appearances, of motives and deeds. The objects that litter Dick’s novels are mostly empty matchbooks and rusty bottle caps, forgotten relics of modern domesticity, but like a latter-day archaeologist of the suburbs, he uncovered their underlying integrity and facticity. At the same time, he subjected his ordinary things and citizens to a bracing and expansive doubt.

Paranoia is the flip side of omniscience; and so it is not surprising that the paranoid writer became a writer about God. Dick’s social and psychological doubt was finally a kind of metaphysical doubt. He was exercised less by hidden intentions than by hidden substances. His fascination with the invisible foundations of the modern city led him to confront the problem of invisible foundations. And the breakdown of modern buildings and streets, which exposed the stuff of which they were really made, taught him that breakdown was also the occasion when hidden things might be revealed. In the most literal and physical way, modern life introduced Dick to the occult.

Dick was an esoteric writer who proposed dramatic revisions of reality whenever the inspiration came to him. But even at his most arcane, he was aware of the vulnerabilities and uncertainties of ordinary people. (The very antithesis of a Philip Dick character would be Arnold Schwarzenegger, who was disastrously miscast as the hero of Total Recall.) He did not believe that the arrival of universal simulation and information theory required the writer to relinquish his grasp on reality or to jettison his moral imagination. Rather, he regarded the novel as a laboratory in which to measure the tangibility of things and the shocks of sentience. Visionary literature and realistic fiction, fantasy and conscience, rarely meet. It took a man whose hunger was the match of his instability to bring them together.

References

Nicole Panter, at NoSuchThingAsWas

Nicole Panter, at PunkGlobe

Nicole Panter’s Flickr Photostream (Note especially this great image at Frogtown, Ca.)

Alexander Star’s essays and articles (1996 through 2008), at Slate (Note particularly The Filming of Philip K. Dick, from April 25, 2002)