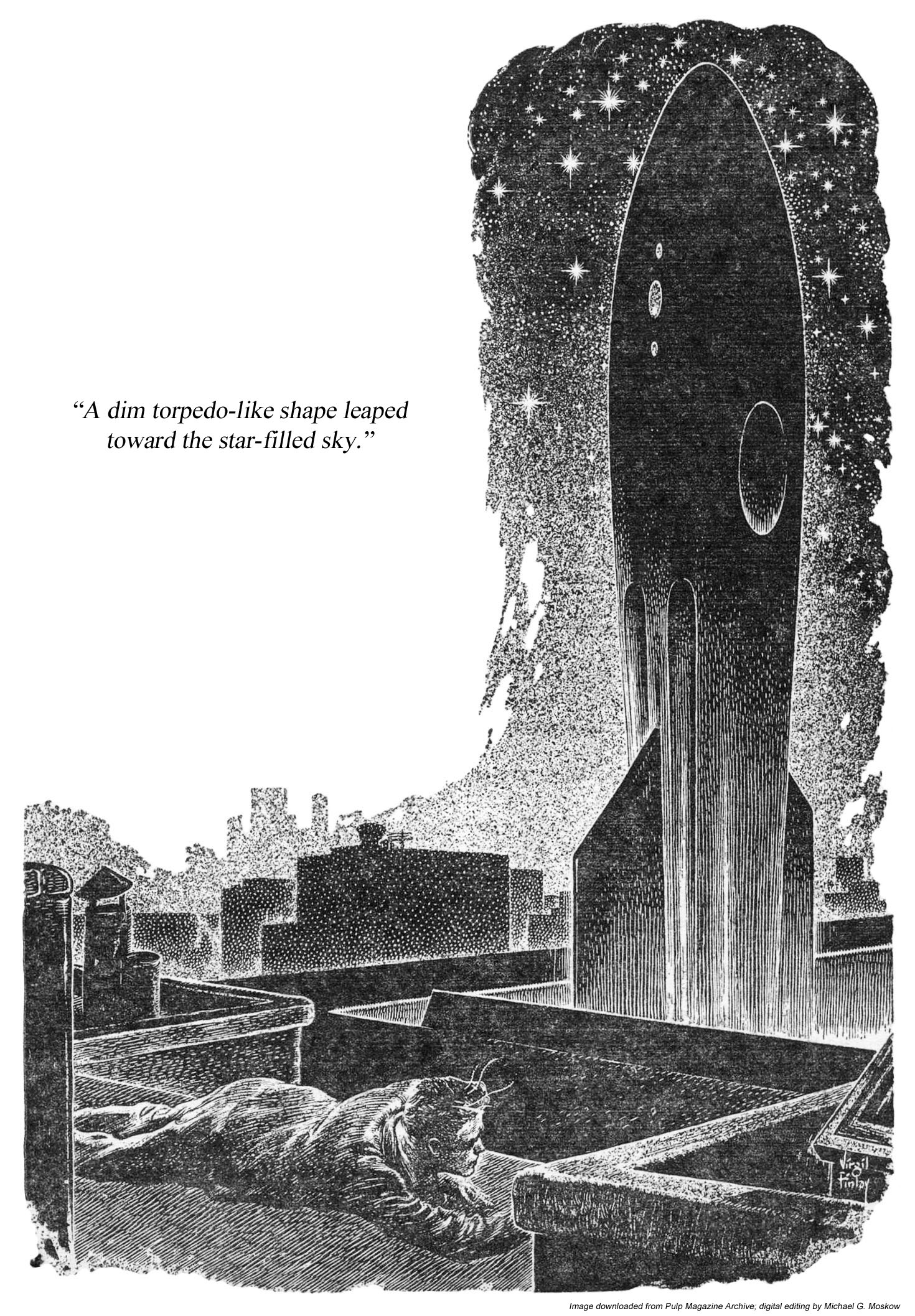

“Slan” was originally serialized in Astounding Science Fiction (September, October, November and December, 1940), with illustrations by Charles Schneeman. The above-mentioned issues are “view-able” through the astounding (pun intended) Luminist Archive. Reprinted in its entirety in Fantastic Story Magazine in 1952, the story was accompanied by three illustrations – shown below – created by Virgil Finlay.

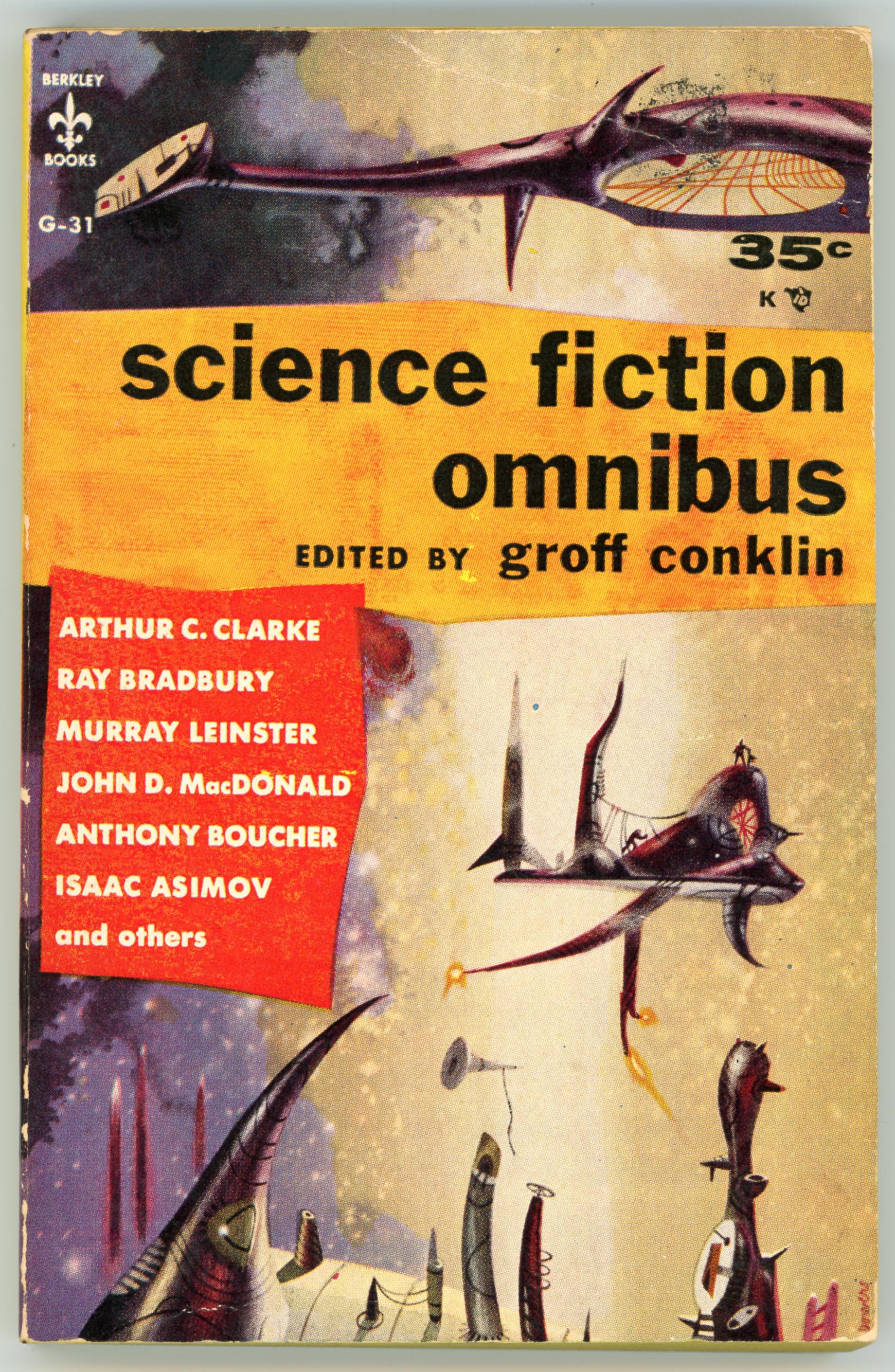

Since creating this post back in January of 2020 (was it that long ago?!) I’ve been fortunate enough to acquire a copy of the Summer, 1952 issue of Fantastic Story in excellent condition, the cover of which – shown below – features Alex Schomburg’s art in all its colorful, streamlined, cloudless, undulating, stylistic glory.

This image replaces (!) the scan originally featured in this post, which I’ve now tossed to the bottom of this post.

As well as being evocative and powerful on levels both emotional and intellectual, these illustrations reveal an extraordinary level of intricacy and detail, typical and representative of Finlay’s work. It might strike one as odd, given the quality of Finlay’s work, that only one of his efforts ever appeared in (more accurately, “on”) Astounding Science Fiction, but the explanation for that sad absence can be found here.

As well as being evocative and powerful on levels both emotional and intellectual, these illustrations reveal an extraordinary level of intricacy and detail, typical and representative of Finlay’s work. It might strike one as odd, given the quality of Finlay’s work, that only one of his efforts ever appeared in (more accurately, “on”) Astounding Science Fiction, but the explanation for that sad absence can be found here.

All images presented here were obtained and adapted from Archive.org’s Pulp Magazine Archive, with the Summer 1952 issue of Fantastic Story Magazine being available here.

______________________________

______________________________

______________________________

______________________________

Akin to my recently updated post showing depictions of C’Mell, in Cordwainer Smith’s The Ballad of Lost C’Mell, “this” post, from August of 2018 – showing illustrations for A.E. van Vogt’s Slan – has been updated to present illustrations for Slan from a different – Russian – angle.

The main impetus for the “original” post was to present Virgil Finlay’s wonderful visual interpretation of the story as seen in his three illustrations in the summer, 1952 issue of Fantastic Story magazine: Jommy Cross’ confrontation with slan girl Joanna Hillory; a symbolic portrait of Jommy juxtaposed against a collage of figures representing the persecution of slans by “normal” humans against slans (Jommy’s golden tendrisl prominently displayed); Jommy, at the thirtieth story of a building in Centropolis, witnessing the launch of a spacecraft operated by tendrilless slans.

Befitting Fantastic Story, Finlay’s images are themselves fantastic in detail, symbolism, and visual impact, examples of illustration that are not only stylistically but qualitatively unique in science-fiction – and not just science fiction – illustration.

Giving the significance of Van Vogt’s body of work, it’s unsurprising that it’s been translated into a variety of languages, among which – also unsurprisingly – is Russian. One title under which Van Vogt’s stories have appeared in the Russian language translation is “Gibroidy” (Гиброиды), or Hybrids, published by Kanon (Канон) publishers in Moscow in 1995, Gibrodiy being one of Kanon’s three compilations of Van Vogt’s works. A list of seven other Russian-language translations of Van Vogt’s works – 5 books and 2 other items – can be found at Electronic Bookshelves by Vadim Ershov and Company) where these works can be downloaded as zip files.

Hybrids comprises three stories:

1) “Voyna Protiv Rullov” (Война Против Руллов) – The War Against the Rull, translated by Viktor Vyacheslavovich Antonov (Виктор Вячеславович Антонов)

2) “Slen” (Слен) – Slan, translated by Yu. K. Semenychev (Ю.К. Семёнычев)

3) “Gibroidy” (Гиброиды) – Hybrids (main title), translated by V. Goryaev (В. Горяев)

The other two titles are:

“Zver” (Зверь) – The Beast, published 1994

Zver includes three stories:

1) “A Dom Stoit Sebe Srokoyno” (А Дом Стоит Себе Срокойно) – The House That Stood Still, translated by Yu. K. Semenychev (Ю.К. Семёнычев)

2) “Tvorets Vselennoy” (Творец Вселенной) – The Universe Maker, translated by I. Shcherbakova (И. Щербаковой)

3) “Zver” (Зверь) – The Beast (main title), translated by I. Boyko (И.Бойко)

“Dvoyniki” (Двойники) – The Reflected Men, published 1995

Dvoyniki includes six stories:

1) “Deti Budushchego” (Дети Будущего) – Children of Tomorrow, translated by K. Prostovoy (К.Простовой)

2) “Vladiki Vremeni” (Владыки Времери) – Time Lords, translated by I. Shcherbakova (И. Щербаковой)

3) “Dvoyniki” (Двойники) – The Reflected Men (main title)

translated by Viktor Vyacheslavovich Antonov (Виктор Вячеславович Антонов)

4) “Loobyashchie Androidi” (Любящие Андроиды) – All The Loving Androids, translated by Viktor Vyacheslavovich Antonov (Виктор Вячеславович Антонов)

5) “Neistrebimie” (Неистребимые) – The Replicators, translated by Yu. K. Semenychev (Ю.К. Семёнычев)

6) “Uskolznuvshee iz Ruk Chudo” (Ускользнувшее из Рук Чудо) – Secret Unattainable, translated by I. Shcherbakova (И. Щербаковой)

______________________________

Front Cover of “Gibroidy” (Гиброиды) – Hybrids

Front Cover of “Gibroidy” (Гиброиды) – Hybrids

______________________________

Front Cover of “Zver” (Зверь) – The Beast. Note the similarity of the building to the police headquarters in (the original) Blade Runner, as seen in this video – “Blade Runner spinner lift-off (’82 theatrical release version)” – from the YouTube channel of Damon Packard II.

Front Cover of “Zver” (Зверь) – The Beast. Note the similarity of the building to the police headquarters in (the original) Blade Runner, as seen in this video – “Blade Runner spinner lift-off (’82 theatrical release version)” – from the YouTube channel of Damon Packard II.

______________________________

Front cover of “Dvoyniki” (Двойники) – The Reflected Men

Front cover of “Dvoyniki” (Двойники) – The Reflected Men

________________________________________

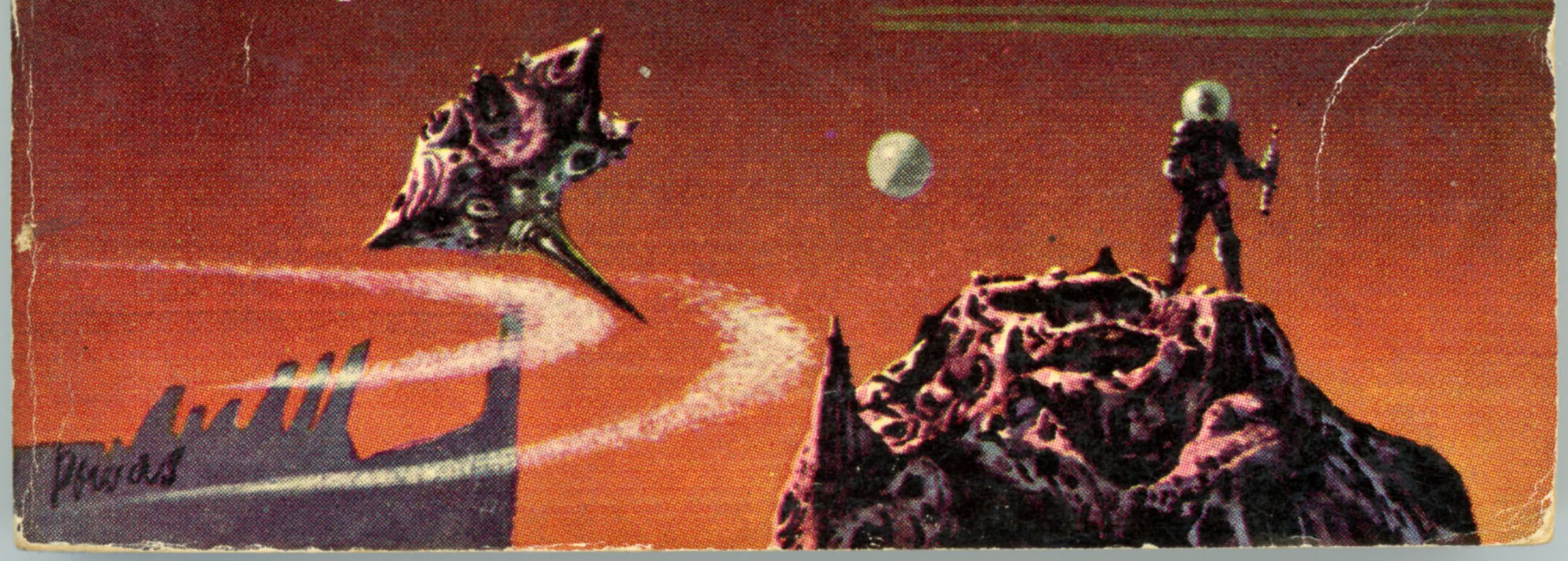

Aside from van Vogt’s original authorship, the one commonality among the three Russian translation is their illustrator: Ilya Evgenevich Voronin. His black and white sketches – in a style akin to that of Dan Adkins – appear as a single illustration in the title page of each work, while each of the stories within is headed by an illustration pertinent to that story.

In this, Слен is no exception, the lead image depicting Jommy Cross coming upon the departure of a tendrilless slan spacecraft from Centropolis, with Granny looking on…

Ilya Voronin’s illustration for Slan, on page 79 of “Gibroidy” (Гиброиды) – Hybrids.

Ilya Voronin’s illustration for Slan, on page 79 of “Gibroidy” (Гиброиды) – Hybrids.

______________________________

“He knew that by no logic could that gauntlet of corridor be considered safe.

At any moment a door might open,

or wisps of thought warn him of men coming around some bend.

With abrupt decision, he slowed his headlong rush and tried several doors.

The fourth door yielded to pressure, and Jommy crossed the threshold with a sense of triumph.

On the far side of the room was a tall, broad window.

He pushed the window open and scrambled out onto the wide sill.

Crouching low, he peered over the ledge.

Light came dimly from the other windows of the building,

and by its glow he could see what appeared to be a narrow driveway wedged between two precipices of brick wall.

For an instant he hesitated and then, like a human fly,

started up the brick wall.

The climbing was simple enough;

enormously strong fingers searched with swift sureness for rough edges.

The deepening darkness, as he climbed, was hampering,

but with every upward step his confidence surged stronger within him.

There were miles of roof here and, if he remembered rightly,

the airport buildings connected on every side with other buildings.

What chance had slans who could not read minds against a slan who could avoid their every trap?

The thirtieth, and top, story!

With a sigh of relief, Jommy pulled himself erect and started along the flat roof.

It was nearly dark now,

but he could see the top of a neighboring building that almost touched the roof he was on.

A leap of two yards at most, an easy jump.

With a loud clang! the clock in a nearby tower began to intone the hour.

One – two – five – ten!

And on the stroke, a low, grinding noise struck Jommy’s ears,

and suddenly, in the shadowy center of that expanse of roof opposite him yawned a wide,

black hole. Startled, he flung himself flat, holding his breath.

And from that dark hole a dim torpedo-like shape leaped into the star-filled sky.

Faster, faster it went; and then, at the uttermost limit of vision,

a tiny, blazing light sprang from its rear.

It flickered there for a moment, then was gone, like a star snuffed out.

Jommy lay very still, his eyes straining to follow the path of the strange craft.

A spaceship.

By all the heavens, a spaceship!

Had these tendrilless slans realized the dream of the ages—to operate flights to the planets?

If so, how had they kept it secret from human beings?

And what were the true slans doing?” (pp. 30-31)

References

Fantastic Story Quarterly / Fantastic Story Magazine, at Wikipedia

Luminist Archive, at LuministOrg

Slan, at Wikipedia

Slan (full text), at Prospero’s Isle

Science Fiction Laboratory (in Russian), at FantLab.ru

Ilya Evgenevich Voronin (in Russian), at FantLab.ru

Ilya Evgenevich Voronin (In Russian), at LibRuSec.ru

Virgil Finlay, at Wikipedia

Virgil Finlay, at WordsEnvisioned

_________________________

January 2020 362