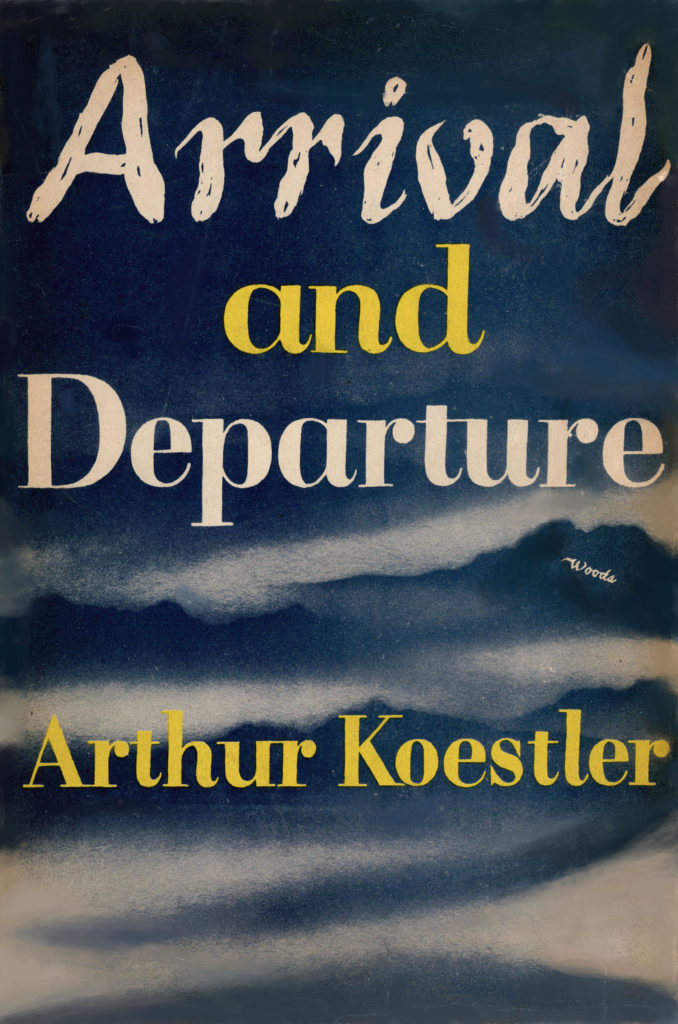

What, after all, was courage?

A matter of glands, nerves; patterns of reaction conditioned by

heredity and early experiences.

A drop of iodine less in the thyroid,

a sadistic governess or over-affectionate aunt,

a slight variation in the electrical resistance

of the medullary ganglions,

and the hero became a coward;

a patriot a traitor.

Touched with the magic rod of cause and effect,

the reactions of men were emptied of their so-called moral contents

as a Leyden jar is discharged by the touch of a conductor.

‘Why do they look at me that way?’

‘Why do they look at me that way?’

‘They don’t look. It’s only your imagination.’

‘They ask themselves: What is he doing here?

Why does he not go where he belongs?’

‘But you belong nowhere, you fool.’

‘How can one live, belonging nowhere?’

‘You belong to yourself. That is the gift I made you.’

‘I don’t want it. Your gift is out of season.’

‘Then what do you want?’

‘Not to be ashamed of myself.’

‘What are you ashamed of?’

‘Of walking through the parks while others

get drowned or burned alive;

of belonging to myself while everybody belongs to something else.’

‘Do you still believe in their big words and little flags?’

‘No, I don’t.’

‘Are you not glad that I opened your eyes?’

‘Yes, I am.’

‘What were your beliefs?’

‘Illusions.’

‘Your search of fraternity?’

‘A wild goose chase.’

‘Your courage?’

‘Vanity.’

‘Your loyalty?’

‘Atonment.’

‘Why then do you want to start again?’

‘Why, indeed? That should be your job to explain.’

But that precisely was the point which Sonia could not explain,

for apparently it was placed on a plane beyond her reasoning,

and perhaps beyond reason altogether.

Don’t be a fool, said Sonia’s voice.

Don’t be a fool, said Sonia’s voice.

This is the ark and behind you is the flood.

That land is doomed and it will rain on it

forty nights and forty days.

Who has ever heard of an inmate of the ark

jumping overboard to walk back into the rising flood?

But why not, Sonia? There is something missing in that story.

There should have been at least one

who ran back into the rain,

to perish with those who had no planks under their feet…

Go on, said Sonia’s voice.

Go on, what happened to that fool after he went back?

The Lord who saw into that man’s heart became ashamed of himself;

and he reached out with his hand to keep that man dry in the rain…

* * * * * * * * * * * *

“Do you mean,” Peter stuttered,

“that you have done what you did – just as a sport?”

The other shrugged.

His attention was focused on the task of drinking from the glass

without spilling any of its contents.

“Don’t you think,” he said at last,

“that it is rather a boring game,

trying to find out one’s reasons for doing something?”