(This is the second of two posts describing the digest-format science fiction anthology Wonder Stories, which was published with generally similar content in 1957 and 1963, featuring cover art of the same general theme by Richard M. Powers. As such, though the content of both magazines s similar, significant differences between the two editions are explained and made clear in each post. So, for those in a hurry (who’s not in a hurry in the world of 2025?!) you can jump to the post for the 1957 edition, “here“.)

The best way to impart a sense of literary wonder, is through awe, mystery, and a sense of the unknown. Such is so for this second – 1963 – edition of Standard Magazines’ (otherwise known as Thrilling Publication’) anthology Wonder Stories, which is comprised of stories from early 50s editions of Startling Stories and Thrilling Wonder Stories, as well as Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.’s tale “Thanasphere”, all these stores having appeared in the 1957 edition of the anthology.

You can learn the story of Wonder Stories, and “other reprints from the Thrilling group”, at Todd Mason’s Sweet Freedom blog.

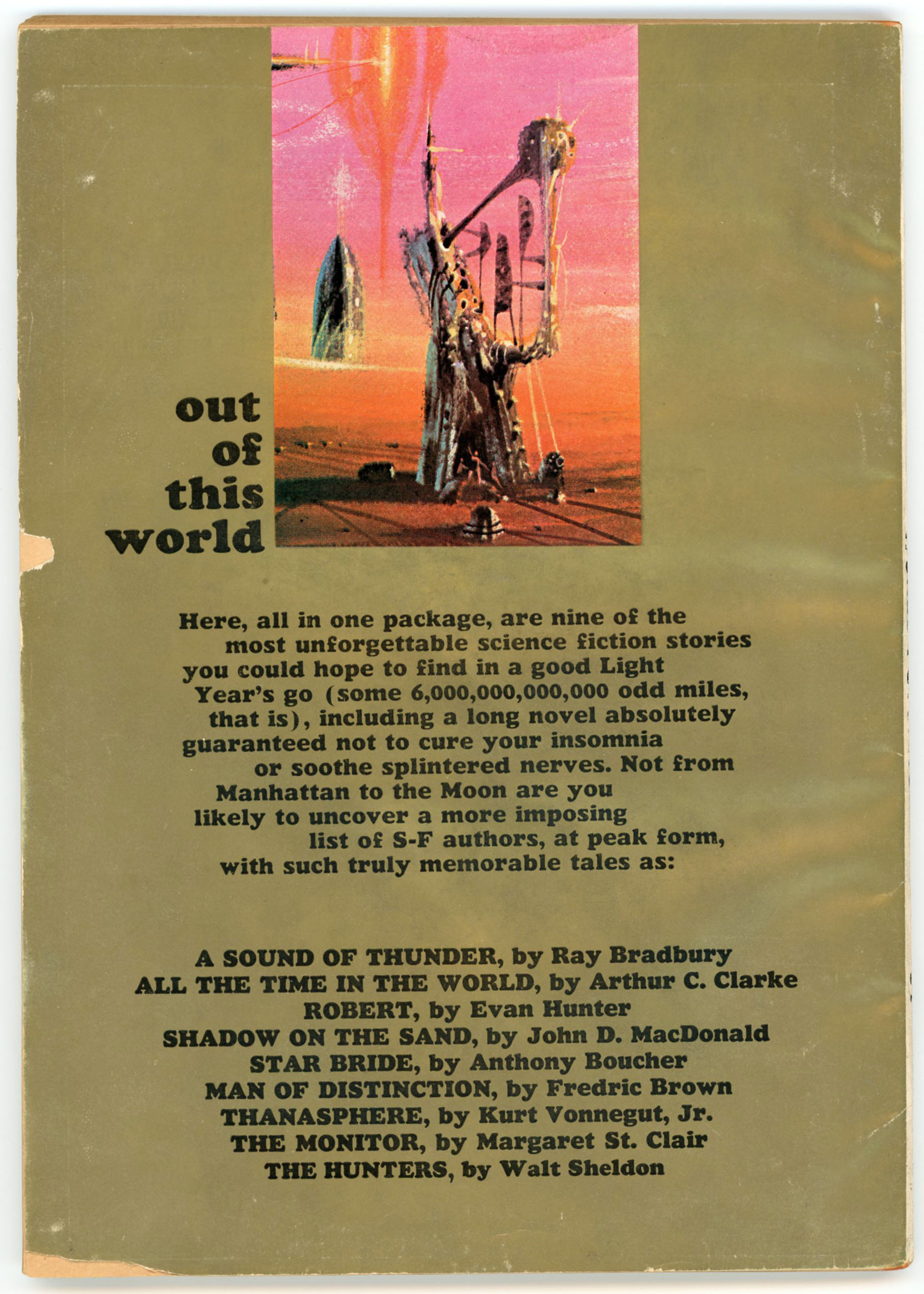

A sense of wonder arises from the anthology’s cover, which is one of the very few pulp magazine cover paintings by Richard M. Powers, whose forte overwhelmingly comprised cover art for paperback books, especially those of Ballantine. His limited oeuvre of magazine covers appeared in early issues of Galaxy Science Fiction, and also included a magnificent painting for the first issue of Beyond Fantasy Fiction.

Typical of Powers’ cover art, the 1963 cover art of Wonder Stories – akin to its 1957 predecessor – sets up a mood; a feeling; an impression beyond words – that has absolutely no relationship to or basis in any of the stories in the anthology. (The same’s true for Powers’ book covers.) Typical of his art, the scene is absent of a recognizable human being, let alone any sign of a human presence. Building on his painting for the 1957 edition, his composition presents shapes emblematic of technology, power, and energy – active even now – situated upon a desert-like alien landscape. Something’s happening, and some sort of thing is happening. But, what?

In coincidental hindsight, the painting anticipates or depicts a scene reminiscent of the ruins of the Ring Builders’ constructions on the planet Ilus IV, from season four of “The Expanse”: Eon-old structures embedded deep (how deep?!) within and extending far above the desert earth, yet still functioning billions of years after their construction, their power undiminished; their potential unchecked. Check out these images of concept art for “The Expanse” at Lee Fitzgerald’s website, to see the resemblance. The Expanse (fandom) also displays an image of the ruins on Ilus.

So, here’s Wonder Stories’ 1963 cover, “as is”…

…and, here’s the art all “niced up”, lightly edited, and “framed” in white, for this post.

I just mentioned the painting’s near-total absence of a human presence. Ah, a minor error! The rear cover, below, presents a cropped view of the lower-right-corner of the cover painting. If you look closely (very and truly and really closely) at this enlarged snippet (just below this rear cover) you might just be able to make out the silhouette of a human form at, and within, the base of this indefinable object.

But, what of the anthology’s contents? Of the stories within, I’m only directly familiar with Ray Bradbury’s “A Sound of Thunder”, Arthur C. Clarke’s “All the Time in the World”, and especially and recently John D. MacDonald’s “Shadow On the Sand”, the latter of which appeared in and inspired the cover art for the October, 1950 issue of Thrilling Wonder Stories. I didn’t actually r e a d MacDonald’s story within my copy of Wonder Stories – the one you see featured in the images above – due to the fragility of my now-61-year-old copy. Instead, I created and printed a PDF of the story from a PDF comprising the entire issue, which I accessed through the Internet Archive.

Having previously encountered very little by and knowing virtually nothing about author John D. MacDonald, I was deeply impressed with “Shadow on On the Sand” on variety of levels, specifically the originality of the plot, and, characters (minor characters, at that) who are not too-two-dimensional stock figures, and who change and evolve with a story’s progression.

MacDonald’s novella is the account of an extraterrestrial totalitarian civilization’s clandestine conquest of Earth utilizing instantaneous superluminal teleportation, and, the impersonation and replacement of human beings via physically altered doppelgangers … albeit the aliens are already (this made writing the story easier, I suppose!) on a superficial level at least … physically and superficially identical to homo sapiens. This is set against and within a backdrop of competition, conflict, and political murder among the aliens’ ruthlessly competitive political parties, military, and clandestine services, with the story’s protagonist going over to the side of humanity by the story’s end. More, I shall not say. It’s a great read. And yet… Unusual for a story penned over seven decades ago, the novella is surprisingly violent, if not genuinely grotesque (“not for the squeamish!”) in parts … albeit violence and horror are neither the center of nor the “drivers” of the plot. The novella is strongly reminiscent of the works of Jack Vance in terms of political and social complexity.

(For a much deeper exploration of MacDonald’s story, read “Shadow On the Sand” at Steve Scott’s blog, “The Trap of Solid Gold – Celebrating the works of John D MacDonald“.)

Otherwise, my reading of “Shadow On the Sand” imparted a sense of curiosity about MacDonald’s body of work, which led to my reading the Fawcett Gold Medal 1978 anthology Other Times, Other Worlds, an anthology of sixteen of his science fiction stories spanning publication between 1948 and 1968. Upon diving into this collection (the paperback edition merited better cover art than a mere astronomical photograph!) I soon realized that I’d read one of his stories previously: this was “Spectator Sport” (originally published in the February, 1950 issue of Thrilling Wonder Stories) first in Fifty Short Science Fiction Tales, and subsequently in Isaac Asimov Presents The Great SF Stories 12. Oddly, this short story features an event that prefigures a plot element “Shadow On the Sand”. (Ironically, I didn’t like “Spectator Sport”!) Regardless, I was and remain deeply impressed by MacDonald’s literary skill in terms of character development, his ability to create an event, setting, scene, and “world” with a modicum of aptly chosen language, and especially, his ability to unflaggingly maintain the pace, mood, and atmosphere of a tale from beginning to end. Only upon reading this anthology and sources elsewhere did I learn that MacDonald more than successfully (extraordinarily so) transitioned from science fiction to mainstream fiction, eventully creating the “Travis McGee” series.

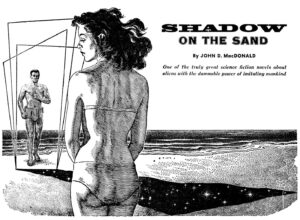

Here’s a nice image of the magazine’s cover. As revealed by the Internet Speculative Fiction Database, the cover and interior artist of this issue are unknown. Otherwise, MacDonald’s story is entirely absent of flying saucers (actually, spacecraft make no appearance in the story), and the characters don’t go around wearing tattered Tarzan-like togas.

This diminutive image appears in the magazine’s table of contents (page 4), adjacent to the story title. The monolith-like slab is a symbol of the teleportation device which is a central plot element and inspiration of the title. The device is essentially invisible to human observers. All that’s apparent is a vague, fleeting, rectangular shadow, which is the portal through which the aliens are transported to Earth.

The only single-page illustration accompanying the story appears on page 15. It shows the arrival of the alien who eventually “goes over” to the side of humanity. Of course, his major inducement is a romantic relationship he unexpectedly (unexpectedly to him!) develops with a woman. MacDonald doesn’t actually describe the appearance of the portal, let alone venture an explanation of its operation. It simply shows up when needed, and then disappears.

The unknown artist’s illustration of the alien civilization’s “shadow” – the teleportation portal – is absent from Wonder Stories, having been replaced by Virgil Finlay’s imaginative portrayal of the scene, which is characterized by his typical attention to detail. Due to the fragility of my copy of the anthology, this image – on pages 2 and 3 – was downloaded (right-clicked) from something known as the “Internet” (!) for display here, on, the, Internet. Oh, yeah, I’m already on, the, Internet. (Like, you!) In reality!… The image here is from the cover of The JDM Bibliophile, Number 17, from March, of 1972. (That’s “JDM”, as in John D. MacDonald. That’s FANAC as in “The Fanac Fan History Project.”)

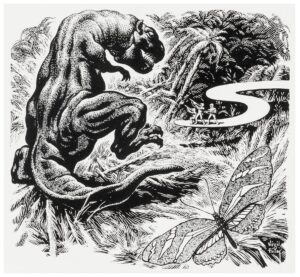

The second story in Wonder Stories is Ray Bradbury’s “A Sound of Thunder“. Though the tale appeared in Planet Stories in 1954, accompanied by a great two-page illustration by Ed Emshwiller, in Wonder Stories, it’s replaced by a Virgil Finlay composition which appears on page 30. The example below is taken from Heritage Auctions, where it was uploaded in September of 2019: “Created in ink over graphite, this small wonder is already beautifully matted and framed with an inside matting area of 4.25″ x 4.25″. Wood silver painted frame, glass front, and outside measurements of 8.5″ x 8.5″. The frame has some small nicks and blemishes but the art is in Excellent condition.”

Wonder Stories was originally published in 1957, and contains six of the stories from this “second” edition. You can view the cover of the former edition, here.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

And, in a sort of conclusion, at this link – here, assuming you read this far! – you can download the PDF version of MacDonald’s story that I created for my own reading.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

So, inside “Wonder Stories” you’ll find what, exactly?

“Shadow on the Sand”, by John D. MacDonald, from Thrilling Wonder Stories, October, 1950 (Also in 1957 edition)

“All the Time in the World” by Arthur C. Clarke, from Startling Stories, July, 1952 (Also in 1957 edition)

“A Sound of Thunder”, by Ray Bradbury, Colliers, from June 28, 1952; also from Planet Stories, January, 1954 (Also in 1957 edition)

“Robert”, by Evan Hunter, from Thrilling Wonder Stories, April, 1953

“The Monitor”, by Margaret St. Clair, from Startling Stories, January, 1954 (Also in 1957 edition)

“The Hunters”, by Walt Sheldon, from Startling Stories, March, 1952

“Man of Distinction”, Fredric Brown, from Thrilling Wonder Stories, February, 1951 (Also in 1957 edition)

“Star Bride”, by Anthony Boucher, from Thrilling Wonder Stories, December, 1951 (Also in 1957 edition)

“Thanasphere”, Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., from Wonder Stories, 1957

…and otherwise…

Wonder Stories, 1963, at…

… Internet Speculative Fiction Database

John D. MacDonald, at…