On reviewing my files, I recently discovered Ian and Betty Ballantine’s fascinating and detailed reminiscence – published in The York New Times Book Review a little over thirty years ago – of their involvement and centrality in the development, growth, and history of paperback books.

In light of Betty Ballantine’s passing earlier this year (on February 12, specifically; Ian having passed away in 1995), I thought it fitting to present the Ballantine’s essay, for informational purposes, and, as a kind of tribute.

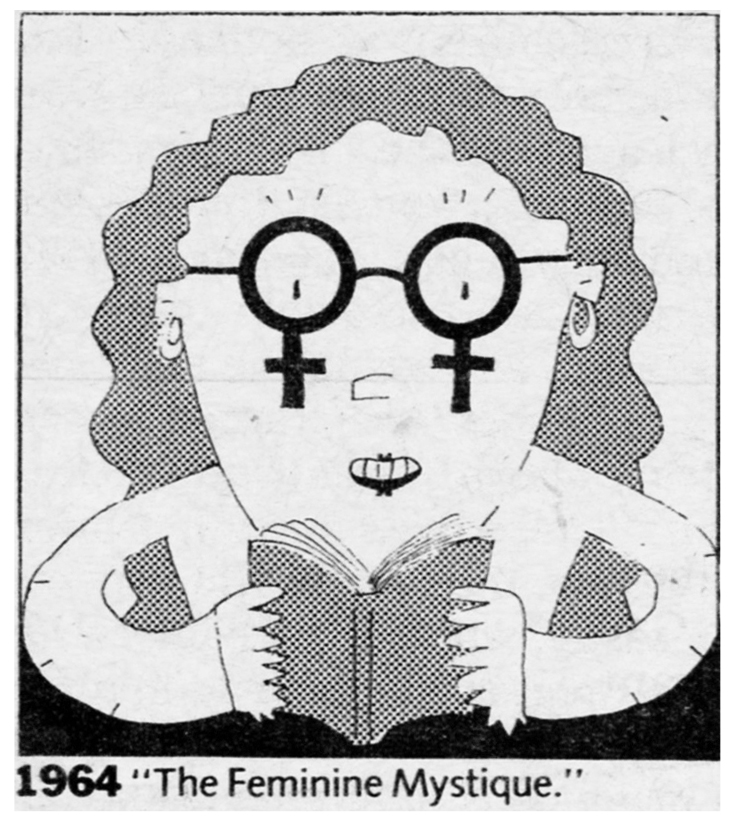

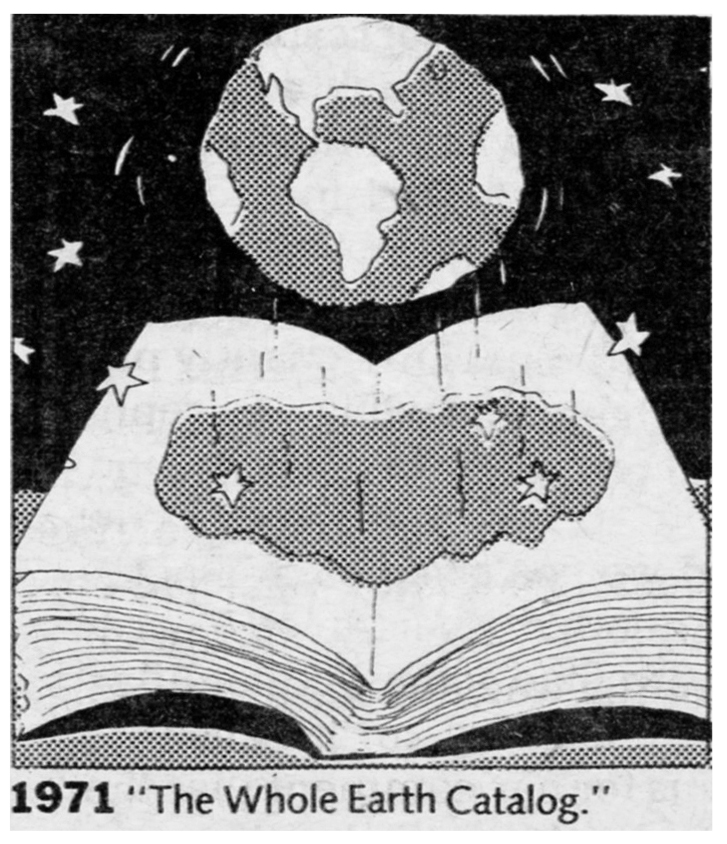

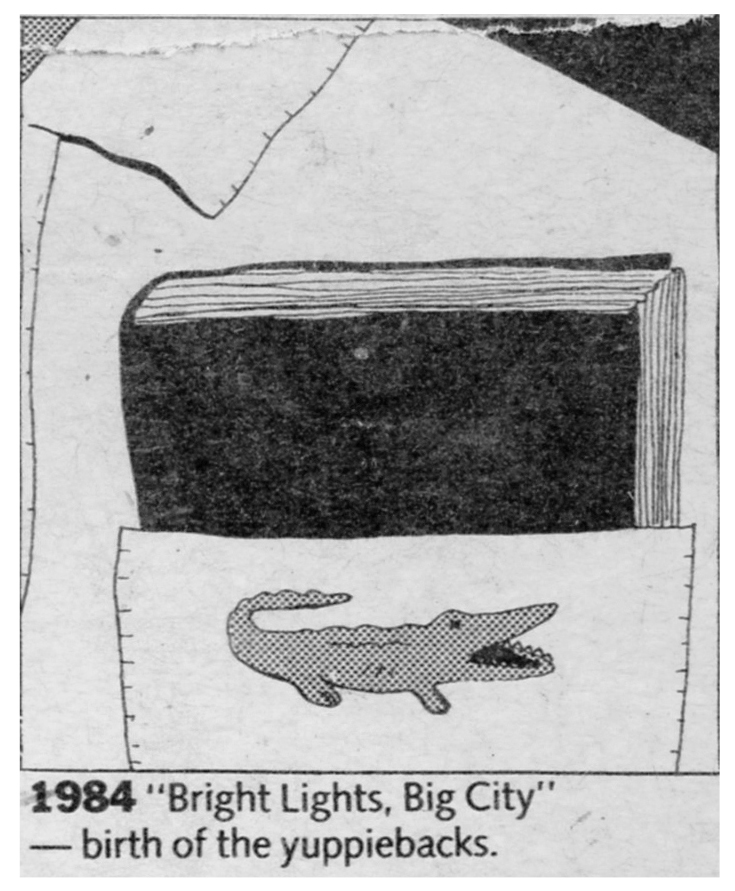

I’ve also included the twelve light-hearted illustrations by Michael Cohen which accompanied the article, and, Ray Walters’ short essay about Pocket Books, which likewise includes its own Cohen illustration.

Paperbacks

From the Two-Bit Beginning

By Ian Ballantine and Betty Ballantine

The New York Times Book Review

April 30, 1989

JUST 50 years ago, in June of 1939, we sailed for New York from Southampton on the Nieuw Amsterdam. Two newly-weds, aged 20 (Betty) and 23 (Ian), setting out to prove that what America needed was paperback books.

We knew war was imminent in Europe, but we were young and confident, determined to launch a relatively new concept in United States publishing by establishing the American branch of Penguin Books, the highly successful English paperbound house founded in 1935 by Allen Lane.

After landing in New York, Betty, born a British subject, spent her first Fourth of July weekend getting acquainted with her American in-laws, then scoured Manhattan for office space. She settled on a seventh-floor loft on East 17th Street, just off Fifth Avenue, furnishing a corner with two secondhand desks, three chairs (one for visitors) and a typewriter. The furniture, a partition, stationery and lumber for shelving in the stockroom took up two-fifths of our cash capital – Betty’s wedding dowry of $500. This left enough for at least two months’ operation, by which time, we were sure, we would be earning money. We hired a stockboy (at $14 a week), and as soon as he, the president (Ian), and the vice president (Betty) had built and stocked the shelving with the first shipment of 50,000 books, Ian set off with an armload of samples to obtain orders from what we were sure was an eagerly waiting book trade.

Ian had nurtured a vision of books in paperback covers – quality reading at low cost – since, as a senior at Columbia in 1938, he had written a paper describing the need for, and the possibilities of, soft-cover publishing. It was an idea he had gone over in detail with his uncle, Saxe Commins, the legendary Random House editor of William Faulkner, Eugene O’Neill and other distinguished authors. But Saxe had strong opinions; he thought paper-bounds in the United States would never work.

There was reason for such gloomy convictions. Boni Books, founded in 1929, mostly a mail-order paperback business, had soon failed. Modern Age Books, founded in 1937, was fast dying, because its owners lacked book marketing savvy. But Ian felt just as strongly that books in paperback could be revolutionary; a year at the London School of Economics, in late 1938 and early ‘39, had confirmed him in his thinking. He had seen at first hand that Penguins, the English sixpenny paperbacks (roughly a dime) were practically like coin of the realm, visible in the hands of everyone, from his professors to every Joe and Jane riding the London tube. The titles published were prestigious and varied. Several of Ian’s professors were editorial advisers to Allen Lane; indeed, it was one of Ian’s professors who introduced him to Lane. Lane wanted Penguins to sell in the United States but had been stymied by the existing copyright laws and had had to turn down many offers from other Americans. Ian researched a solution, whereupon Lane agreed to give Ian and Betty the opportunity to start an American branch that would import his books. The company was owned 49 percent by Ian and 51 percent by Penguin.

For the first year, Penguin’s entire American operation was run from that loft on 17th Street, quarters with which we all became intensely familiar as we worked there 15 to 18 hours a day, seven days a week. In the two successive years, we had to move to even larger lofts – so something was obviously working.

JUST as several teams of scientists announce a breakthrough at the same time, we discovered as we were setting up shop that others had arrived at the same concept by a more conventional route. Months before we arrived, an operation called Pocket Books had begun work on its own paperback line. This was a partnership between Simon & Schuster, a well-established publisher of hard-cover books, and Robert de Graff, a veteran of the hard-cover reprint business. At that time, publishing followed a set pattern – a book was first published in an expensive hard-cover edition at $2 to $3, followed by a hard-cover reprint at 39 cents to 75 cents. Pocket Books would not be in direct competition, since they would be publishing American books, while we would be importers. The principal thing Pockets and Penguins had in common, beside their paper binding, was their price – 25 cents – which inevitably led to their being called “quarter books” or “two-bit books.”

Our own line, Penguins, retained their British look – typographical jackets in bright colors, each designating a particular category, the overall size somewhat larger than that of Pocket Books, which, however, featured illustrated covers and endpapers. At Penguin, with the pick of Allen Lane’s list to choose from, some of the titles we successfully imported included “The Invisible Man” by H.G. Wells, “My Man Jeeves” by P.G. Wodehouse, “Ballet” by Arnold Haskell and a host of novels, biographies and books of travel. Meanwhile, Bob de Graff, over at Pocket, had begun with an excellent list of classic and contemporary American writers, such as “Wuthering Heights” by Emily Bronte and “Lost Horizon” by James Hilton.

A sad fact that both we at Penguin and the people at Pocket had to face was that there were only some 1,500 bookstores in all the United States at that time. Of these, only 500 had really good credit ratings. Americans read magazines. Those addicted to books got their reading matter largely from public libraries and the lending libraries that rented the latest popular titles for a few cents a day. So from the start distribution was the major problem, and solving it the key to success.

WE were actually lucky that Pocket Books was in the field. They had the influence we lacked to make some penetration in the marketplace. Some stores, like the Doubleday chain, accepted both lines right away, and many department stores featured the new books in their displays. (When we began, Macy’s was selling more hard-cover books than any other retailer in New York.) College bookstores, such as the one at Columbia University, were ambivalent. “Carriage trade” bookstores were generally inhospitable. It would be another two decades before paperbacks would gain admittance to the prestigious Scribner Book Store on Fifth Avenue. Even customers who purchased the books found it hard to believe they were getting the whole book, as originally published, for a quarter. Every copy carried a large notice: “Complete and Unabridged!” And even: “Not One Word Cut!” Still, it took years to convince readers that these small books were not digests.

We found that we could get exposure in drugstores and at large newsstands only by providing racks. When this was done, the 25-cent price was so low, even for the times, that readers often made multiple purchases, buying four to eight books at a time. Pete Howe, the intelligently aggressive sales manager at Pocket, persuaded four key magazine wholesalers to handle Pocket Books, and very quickly the salability of paperbounds through “non-book” outlets was proved. Our wide diversity of titles gave Penguin a secure hold in the new marketplace, and we were able to extend our own distribution through the acquisition of a number of salesmen.

We found that we could get exposure in drugstores and at large newsstands only by providing racks. When this was done, the 25-cent price was so low, even for the times, that readers often made multiple purchases, buying four to eight books at a time. Pete Howe, the intelligently aggressive sales manager at Pocket, persuaded four key magazine wholesalers to handle Pocket Books, and very quickly the salability of paperbounds through “non-book” outlets was proved. Our wide diversity of titles gave Penguin a secure hold in the new marketplace, and we were able to extend our own distribution through the acquisition of a number of salesmen.

Inevitably, Britain’s declaration of war against Nazi Germany just before Labor Day of 1939 seriously affected our operations at Penguin. Thanks to the activities of German U-boats, some shipments of books never arrived. Perhaps worse, the physical quality of the books that did reach us steadily deteriorated because of the shortage of paper in England. American Penguins had to go into production for themselves; fortunately, by that time we had done well enough to finance such a project. Our first printing of one of Allen Lane’s war books was Tom Wintringham’s “New Ways of War” – cover art courtesy of Ian’s father, E.J. Ballantine, an actor who also liked to draw and sculpt. Soon, paper restrictions began to affect American publishers as well. After December 1941, wartime problems curtailed the number of magazines, and both Pocket and Penguin gained partial distribution through the big national distributors whose magazine wholesalers served 100,000 newsstands, now hurting for material to sell. Just about anything that could be printed sold, and the sale of paperbound books skyrocketed. Because so many paperbacks were now selling through magazine outlets, magazine publishers got into the business. Between 1941 and 1943, three lines whose owners had magazine backgrounds – Popular Library, Avon and Dell – began appearing in the paperback racks. But lack of paper kept them from growing as fast and as much as they might have.

At Penguin, we were now producing our own original military titles, separate from the British list. Our first native American product, “What’s That Plane?,” was a homemade aircraft recognition book that we all – our editor, Walter B. Pitkin Jr.; his wife, Suzina; E.J. Ballantine, and ourselves – put together around a large dining room table a couple of Sundays after Pearl Harbor. We used British Navy sources for our silhouettes of Japanese aircraft.

At Penguin, we were now producing our own original military titles, separate from the British list. Our first native American product, “What’s That Plane?,” was a homemade aircraft recognition book that we all – our editor, Walter B. Pitkin Jr.; his wife, Suzina; E.J. Ballantine, and ourselves – put together around a large dining room table a couple of Sundays after Pearl Harbor. We used British Navy sources for our silhouettes of Japanese aircraft.

By mid-1942 we had ten salesmen and a staff of seven, including Kurt Enoch, who would eventually create the prestigious New American Library, and we were now producing just about all our titles, the military books co-published with The Infantry Journal, an official publication of the United States Army, together with many war-oriented reprints. Imports were a thing of the past.

We published a special edition of “The Moon Is Down” by John Steinbeck, made for the Army Library Service only, presaging the formation of the Armed Services Editions, which would eventually include some of the most prestigious literary works from all the publishers to create free libraries for the servicemen in the field. The war would produce, among other things, a generation of confirmed paperbound book readers.

We published a special edition of “The Moon Is Down” by John Steinbeck, made for the Army Library Service only, presaging the formation of the Armed Services Editions, which would eventually include some of the most prestigious literary works from all the publishers to create free libraries for the servicemen in the field. The war would produce, among other things, a generation of confirmed paperbound book readers.

Right after the end of the war, we resigned from Penguin Books. We thought that more of the titles should be American-oriented, with covers designed to appeal to American tastes, while Lane felt the American branch should resume being an importer of British books. Ian founded Bantam Books in 1945, bringing together a group of hardcover publishers plus the Book-of-the-Month Club and the Curtis Publishing Company as owners of the new company.

We started by reprinting major novelists such as F. Scott Fitzgerald, John Hersey and Ernest Hemingway, and developed major historical novels and westerns as new categories for paperbounds. And we sought out new areas of interest with books like “Roosevelt and Hopkins” by Robert E. Sherwood, “Hiroshima” by John Hersey and “Ordeal by Slander” by Owen Lattimore. These were controversial books, at least in the paperbound marketplace. Innovation is not something that generally appeals to boards of directors, however, and the introduction of each new category demanded much maneuvering. One of the biggest crises occurred when we wanted to increase prices to open up our publishing to longer books. A six-month battle resulted in our going from 25 cents to 35 cents. With the 25-cent barrier broken at last, and with the longer paperbound books that resulted, the industry had an opportunity to push into new fields. The higher prices could also increase royalty earnings for authors. The early paperback reprinters, who previously had decades of hard-cover publications to draw on for their lists, now began to compete for rights. Guarantees began to leap from the standard $1,500 to startling amounts, like $5,000 and even an occasional dizzying $10,000. For this kind of money, a paperbound publisher could make contracts directly with the authors, who then could retain the entire amount, rather than sharing it 50-50 with a hard-cover publisher.

We started by reprinting major novelists such as F. Scott Fitzgerald, John Hersey and Ernest Hemingway, and developed major historical novels and westerns as new categories for paperbounds. And we sought out new areas of interest with books like “Roosevelt and Hopkins” by Robert E. Sherwood, “Hiroshima” by John Hersey and “Ordeal by Slander” by Owen Lattimore. These were controversial books, at least in the paperbound marketplace. Innovation is not something that generally appeals to boards of directors, however, and the introduction of each new category demanded much maneuvering. One of the biggest crises occurred when we wanted to increase prices to open up our publishing to longer books. A six-month battle resulted in our going from 25 cents to 35 cents. With the 25-cent barrier broken at last, and with the longer paperbound books that resulted, the industry had an opportunity to push into new fields. The higher prices could also increase royalty earnings for authors. The early paperback reprinters, who previously had decades of hard-cover publications to draw on for their lists, now began to compete for rights. Guarantees began to leap from the standard $1,500 to startling amounts, like $5,000 and even an occasional dizzying $10,000. For this kind of money, a paperbound publisher could make contracts directly with the authors, who then could retain the entire amount, rather than sharing it 50-50 with a hard-cover publisher.

INCREASINGLY, we felt the need for freedom to publish what we wanted, and in 1952 we left Bantam to found our own house – Ballantine Books – dedicated initially to publishing only original works. To us, clearly, original publishing was where the field had to go.

Today, the mass marketplace has become the arena in which a reputation is first created; many exciting young writers, many of whose books are reviewed in this section, for instance, appear first in paperback. Hard-cover publication follows. The wheel has come full circle.

Today, the mass marketplace has become the arena in which a reputation is first created; many exciting young writers, many of whose books are reviewed in this section, for instance, appear first in paperback. Hard-cover publication follows. The wheel has come full circle.

As for ourselves, half a century after our marriage, and half a century after the birth of Pocket Books and American Penguin, we are now, we believe, the only surviving founding father and mother of the paperback revolution. We work only on projects that interest us. Bantam provides us with a New York office, and gets first crack at anything we dream up. But our home is actually our workshop and warehouse (things really have come full circle). Best of all, paperback books are now considered by everyone – writers, booksellers, readers – to be real books. Only last month, the Nobel laureate Saul Bellow published his novella “A Theft” as a paperback original.

Happy birthday, paperbacks!

Happy birthday, paperbacks!

Ian Ballantine and Betty Ballantine, founders of Bantam and Ballantine Books, are publishing consultants in New York.

Ian Ballantine and Betty Ballantine, founders of Bantam and Ballantine Books, are publishing consultants in New York.

______________________________

1939: The Birth of the Modern Paperback

“OUT TODAY – THE NEW POCKET BOOKS THAT MAY REVOLUTIONIZE NEW YORK’S READING HABITS.” The advertisement announced Pocket Books’ intention “to open up new frontiers of literature … by distributing low-priced books.” The 4 1/2-inch-by-6 1/3-inch volumes, bound in brightly colored paper covers, cost 25 cents and were sold at drugstores and news-stands as well as bookstores and department stores. The first 10 titles reflected several years of marketing research. Three were the bases of successful movies: Emily Bronte’s “Wuthering Heights,” Thorne Smith’s “Topper” and James Hilton’s “Lost Horizon.” Also included were Thornton Wilder’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, “The Bridge of San Luis Rey”; Agatha Christie’s mystery story “The Murder of Roger Ackroyd”; and “Shakespeare’s Five Great Tragedies.” In its first year, Pocket Books sold a total of six million copies, most notably at outlets where magazines were sold. In the summer of 1939, the British paperback pioneer Penguin Books began selling its line in the United States. – RAY WALTERS

“OUT TODAY – THE NEW POCKET BOOKS THAT MAY REVOLUTIONIZE NEW YORK’S READING HABITS.” The advertisement announced Pocket Books’ intention “to open up new frontiers of literature … by distributing low-priced books.” The 4 1/2-inch-by-6 1/3-inch volumes, bound in brightly colored paper covers, cost 25 cents and were sold at drugstores and news-stands as well as bookstores and department stores. The first 10 titles reflected several years of marketing research. Three were the bases of successful movies: Emily Bronte’s “Wuthering Heights,” Thorne Smith’s “Topper” and James Hilton’s “Lost Horizon.” Also included were Thornton Wilder’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, “The Bridge of San Luis Rey”; Agatha Christie’s mystery story “The Murder of Roger Ackroyd”; and “Shakespeare’s Five Great Tragedies.” In its first year, Pocket Books sold a total of six million copies, most notably at outlets where magazines were sold. In the summer of 1939, the British paperback pioneer Penguin Books began selling its line in the United States. – RAY WALTERS