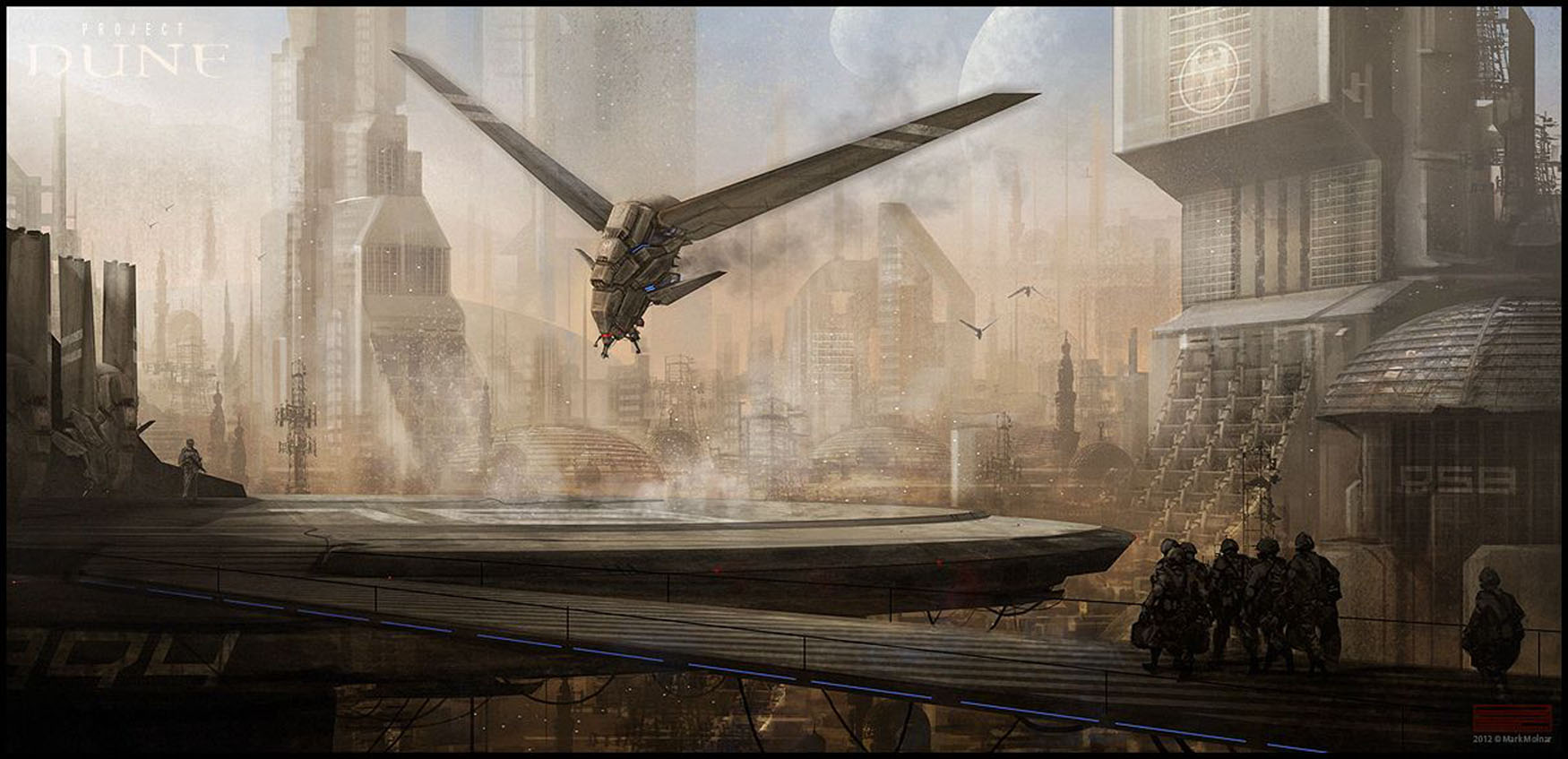

Dennis Villeneuve’s 2021 Dune, the third visual adaptation of Frank Herbert’s 1965 novel (the prior two having been David Lynch’s 1984 film and John Harrison’s 2000 miniseries), was in most respects an excellent film, particularly in the way the director created an entirely vivid and believable “world” – in terms of mood, and atmosphere, and color palette – and on an ostensibly simple yet even more significant level, that of casting and acting. I would not be surprised if the film’s sequel, Dune: Part Two, will attain the same truly high quality.

But, a kind of caveat! I thought the television miniseries was really very good. But, a second kind of caveat! To my own great surprise, there were a few moments in the 2021 movie that were carried off to better effect in Lynch’s film…!

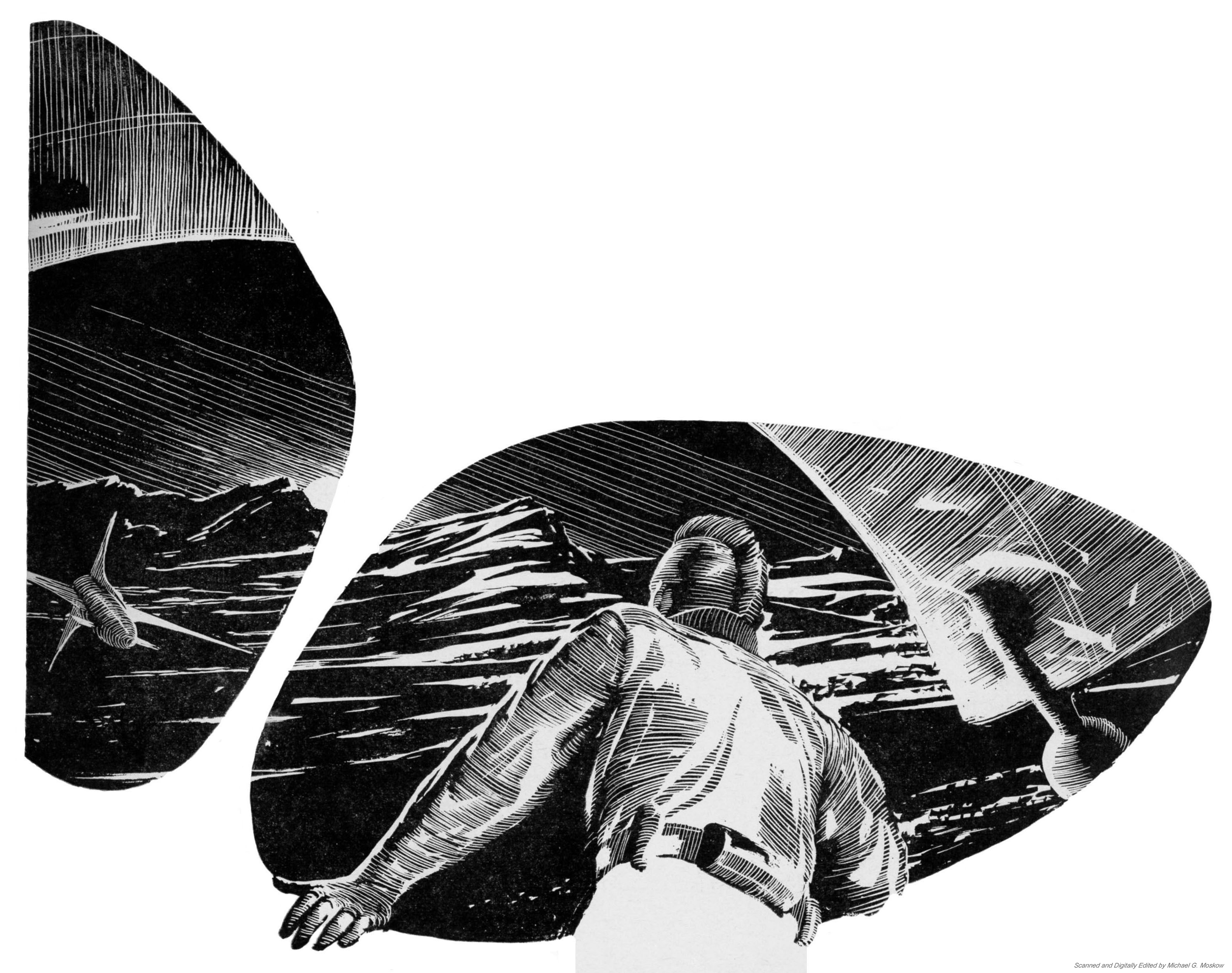

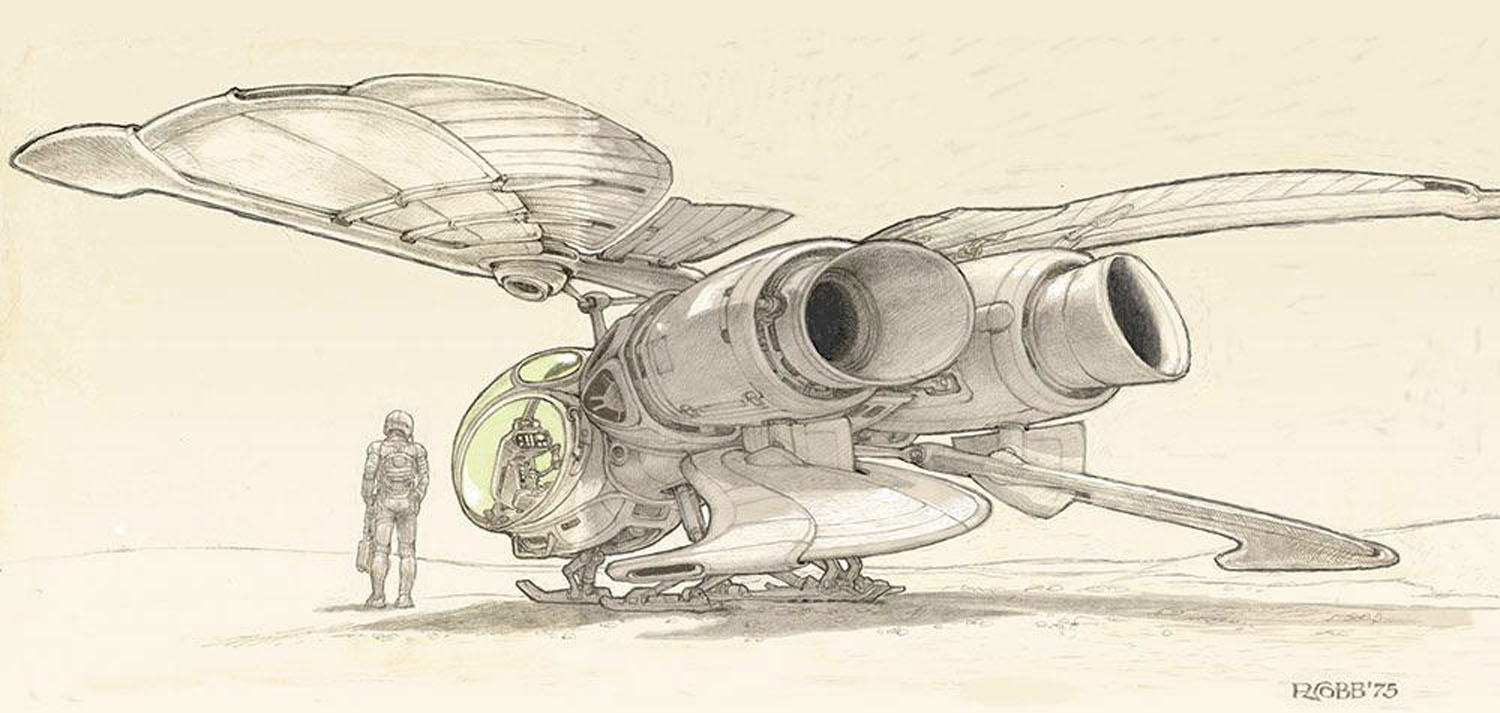

In light of the films’ 2021 advent, I revisited my collection of issues of Analog from December 1963 through February 1964, the publication in which Herbert’s novel was first serialized, to really view the story in its original format. I was particularly curious about John Schoenherr’s depiction of scenes from the novel, in light of how such aspects of the novel were depicted in the book’s film and television adaptations. His art appeared as both cover and interior work, and was thus the first representation of (some) the book’s characters, events, scenes, and 101st century technology. There are, inevitably, differences; there are, interestingly and inevitably, similarities … probably because Herbert’s novel was more character and plot driven than technology driven. (Though technology, of course, is instrumental to the events therein!) And so, the novel’s vagueness in these areas allowed for great latitude in the way the story would be created for a visual medium.

With that, “this” and the next two posts present all of Schoenherr’s interior drawings, and his two cover illustrations (for December ’64 and February ’65, to be specific) for the first – Analog – incarnation of Dune. The majority of the interior art shown in the posts is accompanied by relevant text from Ace Book’s 1969 paperback edition of the novel (for which Schoenherr did the cover art) so that these illustrations can be viewed and appreciated in the proper context.

So, enjoy.

And please remember: Whenever handling Gom Jabbars, wear titanium gloves.

(I worked on these posts back in 2021, and only now am I uploading them. It took me a while. Go figure!)

___________________________________

___________________________________

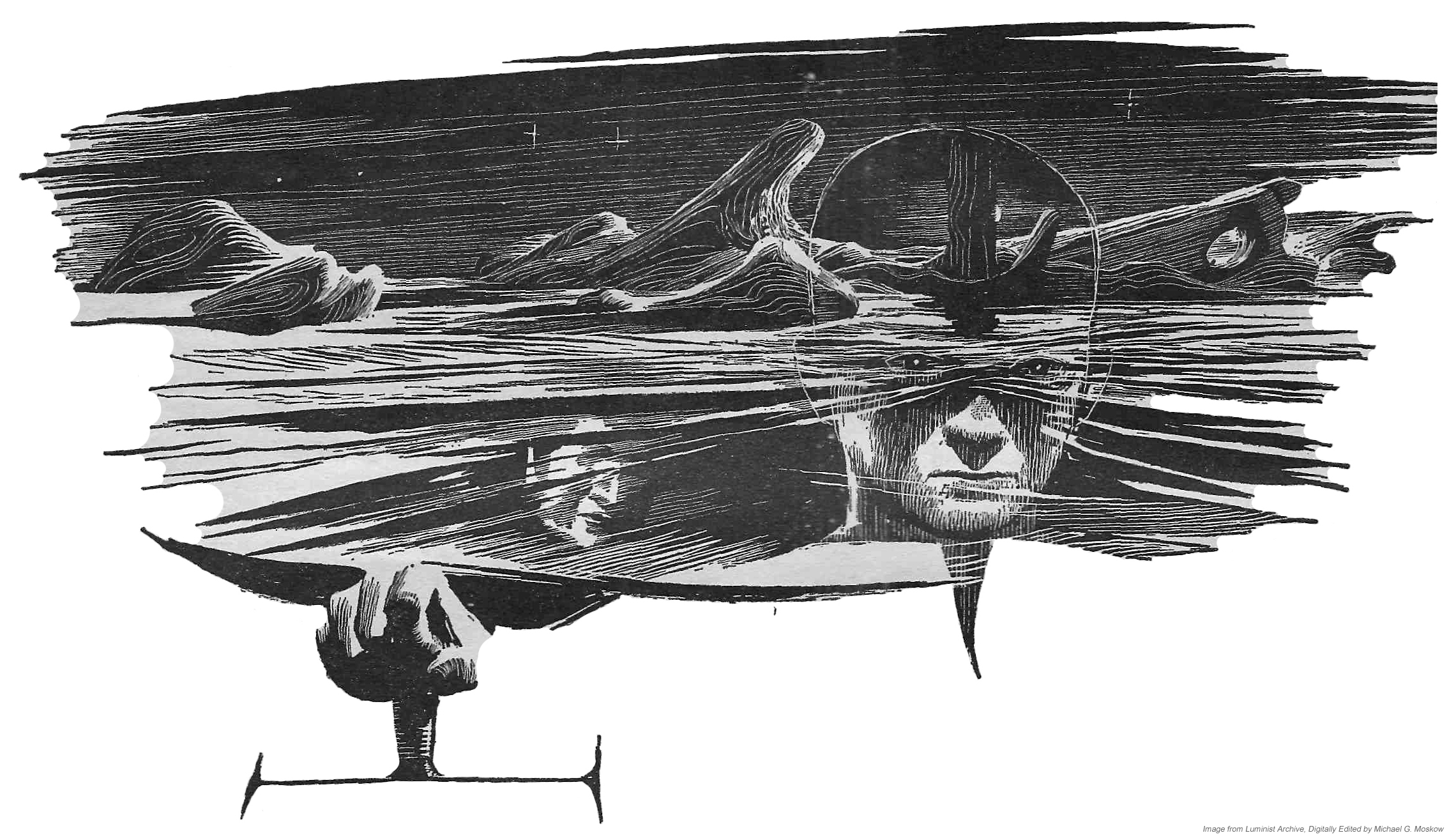

Front cover. Paul Atriedes and his mother, Lady Jessica, flee through the desert of Arrakis after their attempted (and failed!) murder, amidst the Harkonnen attack on Arrakeen.

___________________________________

As above: Paul and Lady Jessica in the desert of Arrakis; thumpers nearby.

Analog, December 1963, p. 22 [Ace 1963, pp. 274-277]

Analog, December 1963, p. 22 [Ace 1963, pp. 274-277]

Paul stepped out of the crack,

watched the sand wave recede across the waste toward the news thumper summons.

Jessica followed, listening.

“Lump … lump … lump … lump … lump … “

Presently the sound stopped.

Paul found the tube in his stillsuit, sipped at the reclaimed water.

Jessica focused on his action,

but her mind felt blank with fatigue and the aftermath of terror.

“Has it gone for sure?” she whispered.

“Somebody called it,” Paul said. “Fremen.”

She felt herself recovering. “It was so big!”

“Not as big as the one that got the ‘thopter.”

“Are you sure it was Fremen?”

“They used a thumper.”

“Why would they help us?”

“Maybe they weren’t helping us.

Maybe they were just calling a worm.”

“Why?”

An answer lay poised on the edge of his awareness,

but refused to come.

He had a vision in his mind of something to do

with the telescoping barbed sticks in their packs – the “maker hooks”.

“Why would they call a worm?” Jessica asked.

A breath of fear touched his mind,

and he forced himself to turn away from his mother,

to look up the cliff.

“We’d better find a way up there before daylight.”

He pointed.

“Those poles we passed – there are more of them.”

She looked, following the line of his hand, saw the poles –

wind-scratched markers –

made out of the shadow of a narrow ledge that twisted into a crevasse high above them.

“They mark a way up the cliff,” Paul said.

He settled his shoulders into the pack,

crossed to the foot of the ledge and began the climb upward.

Jessica waited a moment, resting,

restoring her strength, then she followed.

Up they climbed, following the guide poles

until the ledge dwindled to a narrow lip at the mouth of a dark crevasse.

___________________________________

Paul Atriedes undergoes the test of the Gom Jabbar, with Reverend Mother named Gaius Helen Mohiam behind, observing.

Analog, December 1963, p. 28 [Ace 1963, pp. 15-16]

Analog, December 1963, p. 28 [Ace 1963, pp. 15-16]

“What’s in the box?”

“Pain.”

He felt increased tingling in his hand,

pressed his lips solidly together.

How could this be a test? he wondered.

The tingling became an itch.

The old woman said:

“You’ve heard of animals chewing off a leg to escape a trap?

There’s an animal kind of trick.

A human would remain in the trap,

endure the pain,

feigning death that he might kill the trapper and remove a threat to his kind.”

The itch became the faintest burning.

“Why are you doing this?” he demanded.

“To determine if you’re human.

Be silent.”

Paul clenched his left hand into a fist as the burning sensation increased in the other hand.

It mounted slowly: heat upon heat … upon heat.

He felt the fingernails of his free hand biting the palm.

He tried to flex the fingers of the burning hand, but couldn’t move them.

“It burns,” he whispered.

“Silence!”

Pain throbbed up his arm.

Sweat stood out on his forehead.

Every fiber cried out to withdraw the hand from that burning pit … but …

the gom jabbar.

Without turning his head,

he tried to move his eyes to see that terrible needle poised beside his neck.

He sensed that he was breathing in gasps, tried to slow his breath and couldn’t.

Pain!

His world emptied of everything except that hand immersed in agony,

the ancient face inches away staring at him.

His lips were so dry he had difficulty separating them.

The burning! The burning!

He thought he could feel skin curling back on that agonized hand,

the flesh crisping and dropping away until only charred bone remained.

It stopped!

As though a switch had been turned off, the pain stopped.

Paul felt his right arm trembling, felt sweat bathing his body.

“Enough,” the old woman muttered. “Kull wahad!

No woman child ever withstood that much.

I must’ve wanted you to fail.”

She leaned back, withdrawing the gom jabbar from the side of his neck.

“Take your hand from the box, young human, and look at it.”

___________________________________

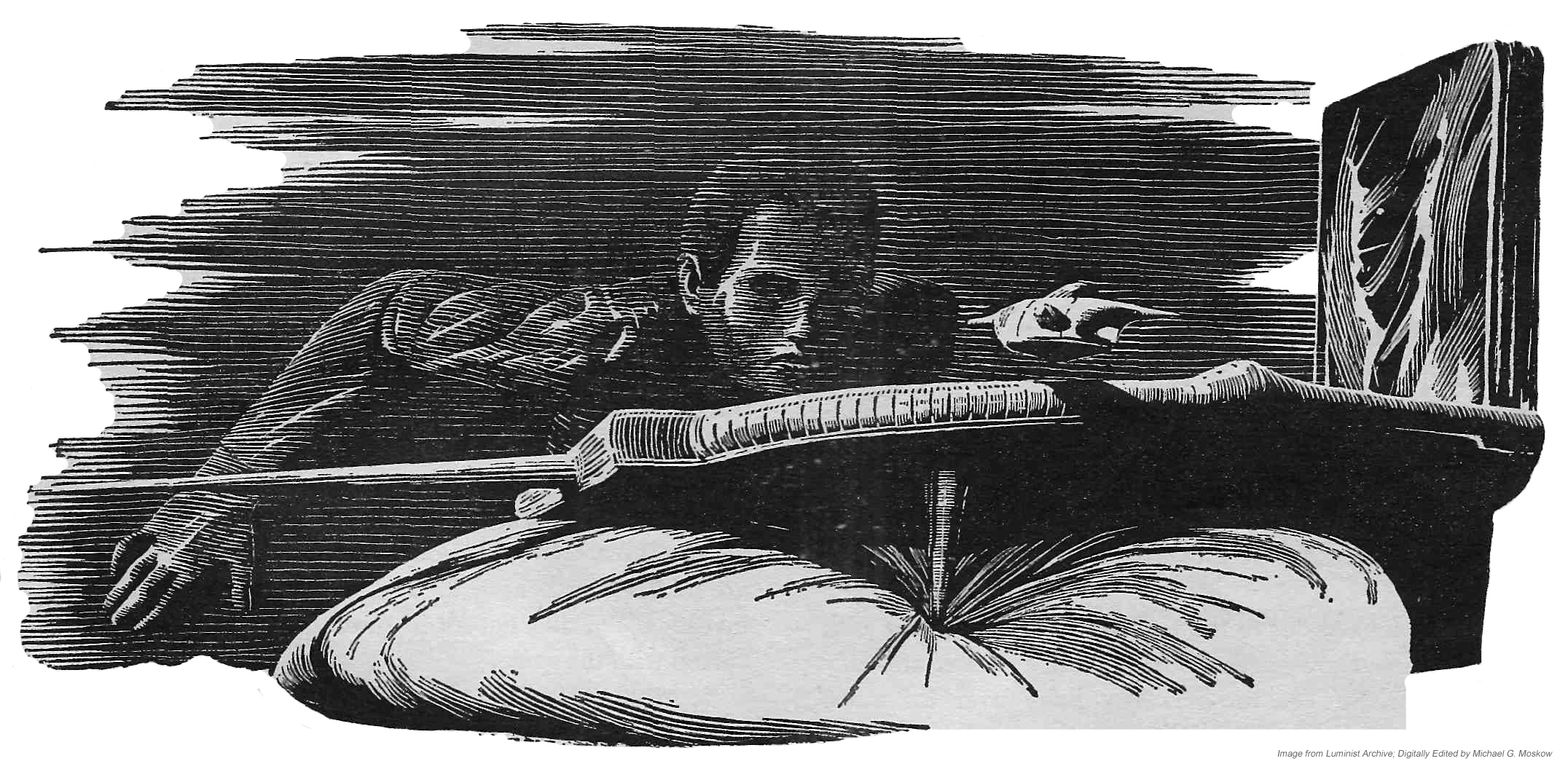

Doctor Wellington Yueh, a the mark of imperial conditioning on his forehead, shows the poison gas tooth – by which he plans to assassinate Baron Vladimir Harkonnen – to the paralyzed Duke Leto Atriedes.

Analog, December 1963, p. 33 [Ace 1963, pp. 167-169]

Analog, December 1963, p. 33 [Ace 1963, pp. 167-169]

Yueh! Leto thought.

He’s sabotaged the house generators! We’re wide open!

Yueh began walking toward him, pocketing a dartgun.

Leto found he could still speak, gasped:

“Yueh! How?”

Then the paralysis reached his legs and he slid to the floor with his back propped against the stone wall.

Yueh’s face carried a look of sadness as he bent over,

touched Leto’s forehead.

The Duke found he could feel the touch, but it was remote … dull.

“The drug on the dart is selective,” Yueh said.

“You can speak, but I’d advise against it.”

He glanced down the hall, and again bent over Leto,

pulled out the dart,

tossed it aside.

The sound of the dart clattering on the stones was faint and distant to the Duke’s ears.

It can’t be Yueh, Leto thought.

He’s conditioned.

“How?” Leto whispered.

“I’m sorry, my dear Duke,

but there are things which will make greater demands than this.”

He touched the diamond tattoo on his forehead.

“I find it very strange, myself –

an override on my pyretic conscience –

but I wish to kill a man.

Yes, I actually wish it.

I will stop at nothing to do it.”

He looked down at the Duke.

“Oh, not you, my dear Duke.

The Baron Harkonnen.

I wish to kill the Baron.”

“Bar … on Har …”

“Be quiet, please, my poor Duke.

You haven’t much time.

That peg tooth I put in your mouth after the tumble at Narcal –

that tooth must be replaced.

In a moment, I’ll render you unconscious and replace that tooth.”

He opened his hand, stared at something in it.

“An exact duplicate, its core shaped most exquisitely like a nerve.

It’ll escape the usual detectors, even a fast scanning.

But if you bite down hard on it, the cover crushes.

Then, when you expel your breath sharply,

you fill the air around you with a poison gas –

most deadly.”

___________________________________

Lady Jessica’s encounter with the housekeeper of the palace of Arrakeen, the Shadout Mapes, who displays her crysknife.

Analog, December 1963, p. 38 [Ace 1963, pp. 60-61]

Analog, December 1963, p. 38 [Ace 1963, pp. 60-61]

“My Lady!” Mapes pleaded.

She appeared about to fall to her knees.

“The weapon was sent as a gift to you should you prove to be the One”

“And as the means of my death should I prove otherwise,” Jessica said.

She waited in the seeming relaxation that made the Bene Gesserit-trained so terrifying in combat.

Now we see which way the decision tips, she thought.

Slowly, Mapes reached into the neck of her dress,

brought out a dark sheath.

A black handle with deep finger ridges protruded from it.

She took sheath in one hand and handle in the other,

withdrew a milk-white blade, held it up.

The blade seemed to shine and glitter with a light of its own.

It was double-edged like a kindjal and the blade was perhaps twenty centimeters long.

“Do you know this, my Lady?” Mapes asked.

It could only be one thing, Jessica knew,

the fabled crysknife of Arrakis,

the blade that had never been taken off the planet,

and was known only by rumor and wild gossip.

“It’s a crysknife,” she said.

“Say it not lightly,” Mapes said.

“Do you know its meaning?”

And Jessica thought: There was an edge to that question.

Here’s the reason this Fremen has taken service with me,

to ask that one question.

My answer could precipitate violence or … what?

She seeks an answer from me: the meaning of a knife.

She’s called the Shadout in the Chakobsa tongue.

Knife, that’s “Death Maker” in Chakobsa.

She’s getting restive.

I must answer now.

Delay is as dangerous as the wrong answer.

Jessica said: “It’s a maker – ”

“Eighe-e-e-e-e-e!” Mapes wailed.

It was a sound of both grief and elation.

She trembled so hard the knife blade sent glittering shards of reflection shooting around the room.

___________________________________

Paul Atriedes remains motionless in an effort to avoid a Harkonnen assassination attempt with a hunter-seeker; his life is saved by the Shadout Mapes.

Analog, December 1963, p. 45 [Analog, December 1963, p. 49, and January 1964, p. 49]

But the hunter-seeker had its limitations.

The compressed suspensor field on which it moved distorted the vision of its transmitter eye.

With nothing but the dim light of this room to reflect his target,

the operator would be relying on motion –

anything that moved.

A shield could slow a seeker,

giving him time to destroy it,

but Paul had put aside his shield on the bed.

The belt had been uncomfortable beneath his back.

Some prime targets for assassins even carried laseguns to knock down seekers,

but laseguns were expensive and notoriously cranky of maintenance,

and there was always the danger of explosive pyrotechnics with them

if the laser beam intersected a hot shield.

The Atriedes had always relied on their body shields and their wits.

Now, Paul had only his wits to meet this threat.

He held himself in near catatonic immobility.

The seeker lifted, swung sideways across the room and back.

It rippled through the slatted light from the windowblinds, back and forth, quartering.

I must try to grab it, Paul thought.

The suspensor field will make it slippery on the bottom, but if I grip tightly …

The hall door behind Paul opened.

The seeker arrowed past his head toward the motion.

Paul’s reaction was a flashing reflex.

His right hand shot out and down,

gripping the deadly thing.

It hummed and twisted in his hand,

but his muscles were locked on it in desperation.

With a violent turn and thrust,

he slammed the seeker’s nose against the metal doorplate.

He felt the crunch of it as the nose eye smashed

and the seeker went dead in his hand, but still he held it … to be certain.

Paul’s eyes came up, met the open stare of total blue from the Shadout Mapes.

“Your father has sent for you,” she said.

“There are men in the hall to escort you some place.”

Paul nodded,

his eyes and awareness focusing on this odd woman in a sacklike dress of bondsman brown.

She was looking now at the thing in his hand.

“I’ve heard of suchlike,” she said. “It could’ve killed me, not so?”

He had to swallow before he could speak. “I … was its target.”

“But it was coming for me.”

“Because you were moving.” And he wondered: Who is this creature?

“And you saved my life then,” she said.

“I saved both our lives.”

These, Too, Will Interest You

Dune…

… at Wikipedia

…at Britannica

… at GoodReads

… at DuneNovels

… at Internet Speculative Fiction Database

… John Schoenherr…

… at Wikipedia

… at Internet Speculative Fiction Database

… at ArtNet

… at Invaluable

And to conclude, John Schoenherr’s obituary, written by Margalit Fox and published in The New York Times on April 14, 2010…

John Schoenherr, Children’s Book Illustrator, Dies at 74

John Schoenherr, a Caldecott Medal-winning illustrator who for a half-century produced painterly, exquisitely detailed images of creatures from this world and others, died on April 8. He was 74 and lived in Delaware Township, N.J.

His death, in a hospital in Easton, Pa., was from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, his son, Ian, said.

A highly regarded nature artist, Mr. Schoenherr illustrated more than 40 children’s titles. He won a Caldecott Medal in 1988 for “Owl Moon” (Philomel, 1987; text by Jane Yolen), the story of a father and daughter who go looking for owls on a cold winter’s night. Presented annually by the American Library Association, the medal honors the best illustrations in a book for young people.

Mr. Schoenherr had a parallel, equally prominent career as a science-fiction illustrator. He was the first artist to depict the world of Frank Herbert’s “Dune” stories, with its vast windswept deserts and huge menacing sandworms. Through the scores of book jackets and pulp magazine covers he drew in the 1950s and afterward including cover art for masters of the field like Philip K. Dick, John Brunner and Anne McCaffrey. Mr. Schoenherr is widely credited with helping shape midcentury America’s collective image of alien landscapes and their occupants.

John Carl Schoenherr, familiarly known as Jack, was born on July 5, 1935, in Manhattan and reared in Queens. Growing up in a German-speaking household in a polyglot community, he used drawings to communicate with his Italian- and Chinese- and English-speaking neighbors. As a young man, he studied at the Art Students League of New York and earned a bachelor of fine arts degree from Pratt Institute, where he failed a class in nature drawing.

Though Mr. Schoenherr planned a career as a painter, in the late 1950s he began a long association with Astounding Science Fiction magazine, later known as Analog.

“Painting was my initial impetus,” he told The Chicago Tribune in 1988. “I just got sidetracked into illustration by things like mortgages and children. Not a bad way to prostitute yourself.”

Mr. Schoenherr was known early on as one of the few commercial illustrators to work mainly on scratchboard, which gave him stark blacks and whites and a level of fine detail that recalled Renaissance woodcuts. In later years he turned to media like watercolors and oils.

In 1965 Mr. Schoenherr won a Hugo Award, presented by the World Science Fiction Society, for his artwork for “Dune,” which first appeared as a serial in Analog. He later provided the cover and interior art for several novels in the “Dune” series and for “The Illustrated Dune” (Berkley, 1978).

It is no small thing to make a worm look terrifying. Mr. Schoenherr did so evocatively, rendering Mr. Herbert’s sand creature as a rearing, pipelike organism whose jagged, gaping maw revealed a terrible blackness within.

In an interview quoted in The New Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (Viking, 1988), Mr. Herbert called Mr. Schoenherr “the only man who has ever visited Dune.”

Mr. Schoenherr’s first children’s book illustrations were for “Rascal: A Memoir of a Better Era” (Dutton, 1963), by Sterling North, about a raccoon. His art for children centered often on the natural world and in particular on mammals. Mr. Schoenherr was especially partial to bears, in all their dark-brown density.

His other children’s titles include “Julie of the Wolves” (Harper & Row, 1972), which won a Newbery Medal for its author, Jean Craighead George; and several he wrote himself, among them “The Barn” (Little, Brown, 1968) and “Bear” (Philomel, 1991).

Mr. Schoenherr’s paintings have been exhibited at museums and galleries throughout North America.

Besides his son, Ian, who is also a well-known children’s book illustrator, Mr. Schoenherr is survived by his wife, the former Judith Gray, whom he married in 1960; a daughter, Jennifer Schoenherr Aiello; three grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren.

If Mr. Schoenherr’s twin careers had a common bond, it was the rigorous fealty with which he drew all life-forms, real or imagined.

“I’ll always be proud of the ‘genuine aliens’ I designed,” Mr. Schoenherr told the journal Artists of the Rockies and the Golden West in 1983. “Never were they humans with insect antennae.”

The second installment of Frank Herbert’s Dune: Analog, January, 1964.

The second installment of Frank Herbert’s Dune: Analog, January, 1964. Analog, January 1964, p. 58 [Ace 1963, pp. 99-100]

Analog, January 1964, p. 58 [Ace 1963, pp. 99-100] Analog, January 1964, pp. 76-77

Analog, January 1964, pp. 76-77 Analog, January 1964, pp. 68-69

Analog, January 1964, pp. 68-69