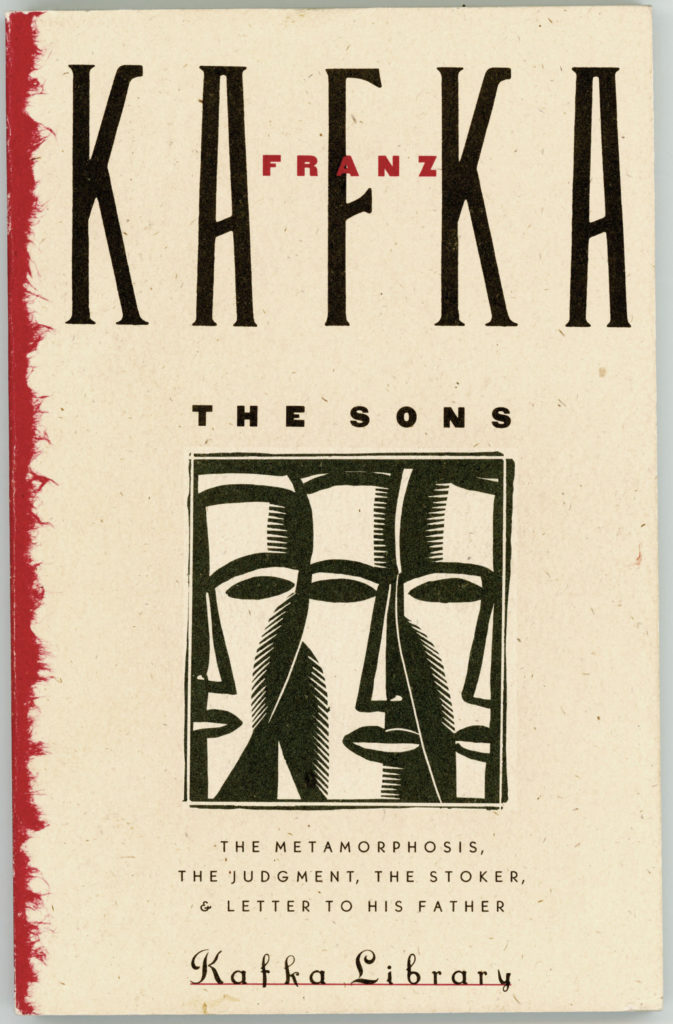

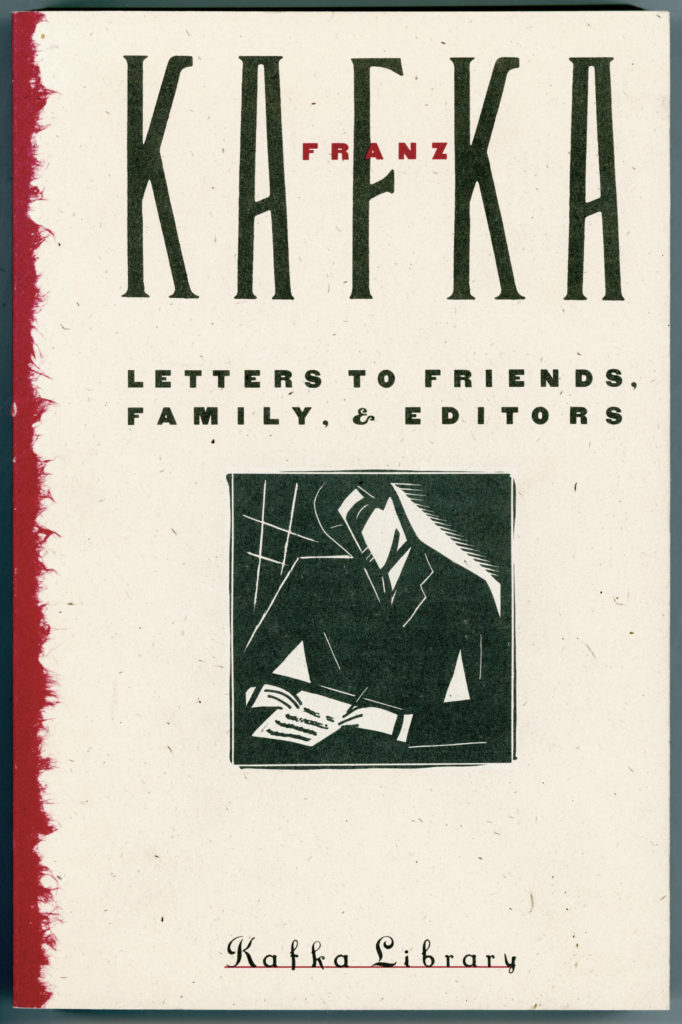

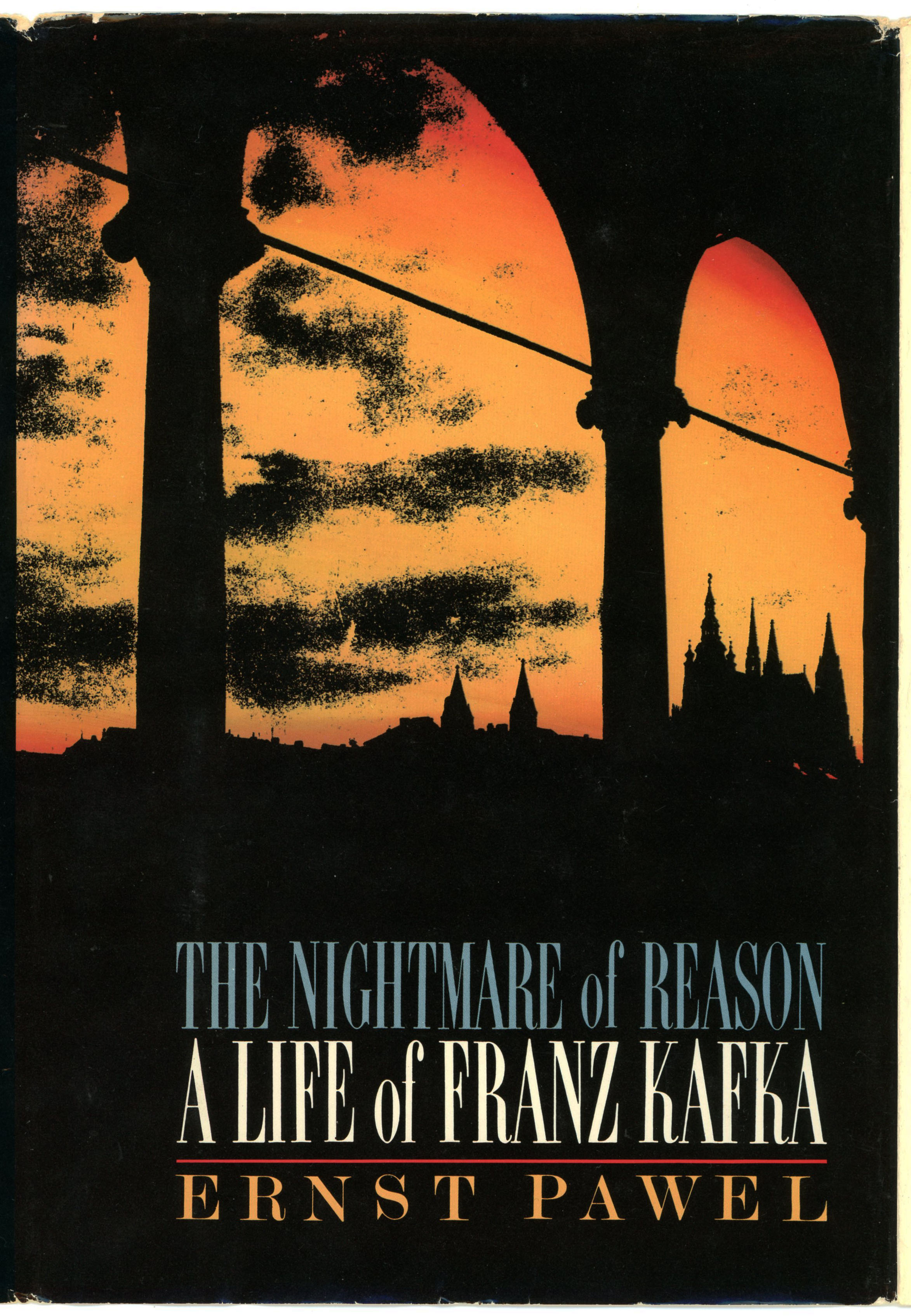

Unlike Anthony Russo’s cover illustrations for the series of Schocken Books titles covering the works of Franz Kafka (published from the late 1980s through the early 1990s), the cover art of Ernst Pawel’s highly praised 1984 biography of Kafka, The Nightmare of Reason – A Life of Franz Kafka (Farrar – Straus – Giroux), is an illustration of a different sort: Jacket designer Candy Jernigan used a photographic silhouette of Prague Castle to symbolize the physical, social, and psychological “world” of Franz Kafka’s writing. Perhaps the image was made from a color negative, with the color saturation of the final image having been enhanced during printing. Or, perhaps the picture is simply an accurate representation of the colors of the Prague skyline at dusk.

Either way, the combination of black-clouded yellow-orange sky, with the castle in the distance, is quite striking.

By way of comparison, this September, 2014 photograph, from Park Inn at Radisson, shows a sunset view of the Castle from the Charles Bridge.

By way of comparison, this September, 2014 photograph, from Park Inn at Radisson, shows a sunset view of the Castle from the Charles Bridge.

________________________________________

Some of Ernst Pawel’s other works include: From the Dark Tower, In The Absence of Magic, Letters of Thomas Mann 1889-1955 (selected and translated from the German by Richard and Clara Winston), Life in Dark Ages: A Memoir, The Island in Time (a novel), The Labyrinth of Exile: A Life of Theodor Herzl, The Poet Dying : Heinrich Heine’s Last Years in Paris, and, Writings of the Nazi Holocaust.

He passed away in 1994.

This is his portrait, by Nancy Crampton, from the book jacket.

________________________________________

________________________________________

Ernst Pawel, 74, Biographer, Dies

The New York Times

Aug. 19, 1994

Section A, Page 24

Ernst Pawel, a novelist and biographer, died on Tuesday at his home in Great Neck, L.I. He was 74.

The cause was lung cancer, his family said.

Mr. Pawel’s 1984 biography of Franz Kafka, “The Nightmare of Reason,” won several prizes, including the Alfred Harcourt Award in biography and memoirs, and was translated into 10 languages. In a review for The New York Times, Christopher Lehmann-Haupt called the work “moving and perceptive.”

Mr. Pawel was also the author of “The Labyrinth of Exile,” a biography of Theodor Herzl, the founder of modern Zionism. He had recently finished a book about the German poet Heinrich Heine and at the time of his death was working on his own memoirs, “Life in the Dark Ages.” Both books are to be published posthumously, his family said.

He was born in 1920 in Breslau, then under German rule but now part of Poland, and fled Nazi Germany with his family in 1933, settling first in Yugoslavia and four years later immigrating to New York City. After serving as a translator for Army intelligence during World War II, he received a bachelor’s degree from the City University of New York.

He was the author of three novels, “The Island of Time” (1950), “The Dark Tower” (1957) and “In the Absence of Magic” (1961), and numerous essays and book reviews. Fluent in a dozen languages, he worked for 36 years as a translator and public relations executive for New York Life Insurance. He retired in 1982.

He is survived by his wife of 51 years, Ruth; a son, Michael, and a daughter, Miriam, both of Manhattan, and a granddaughter.

________________________________________

A Nightmare of Reason was published by Vintage Books in 1985, in trade paperback format. (Unfortunately, I don’t know the cover artist’s name!)