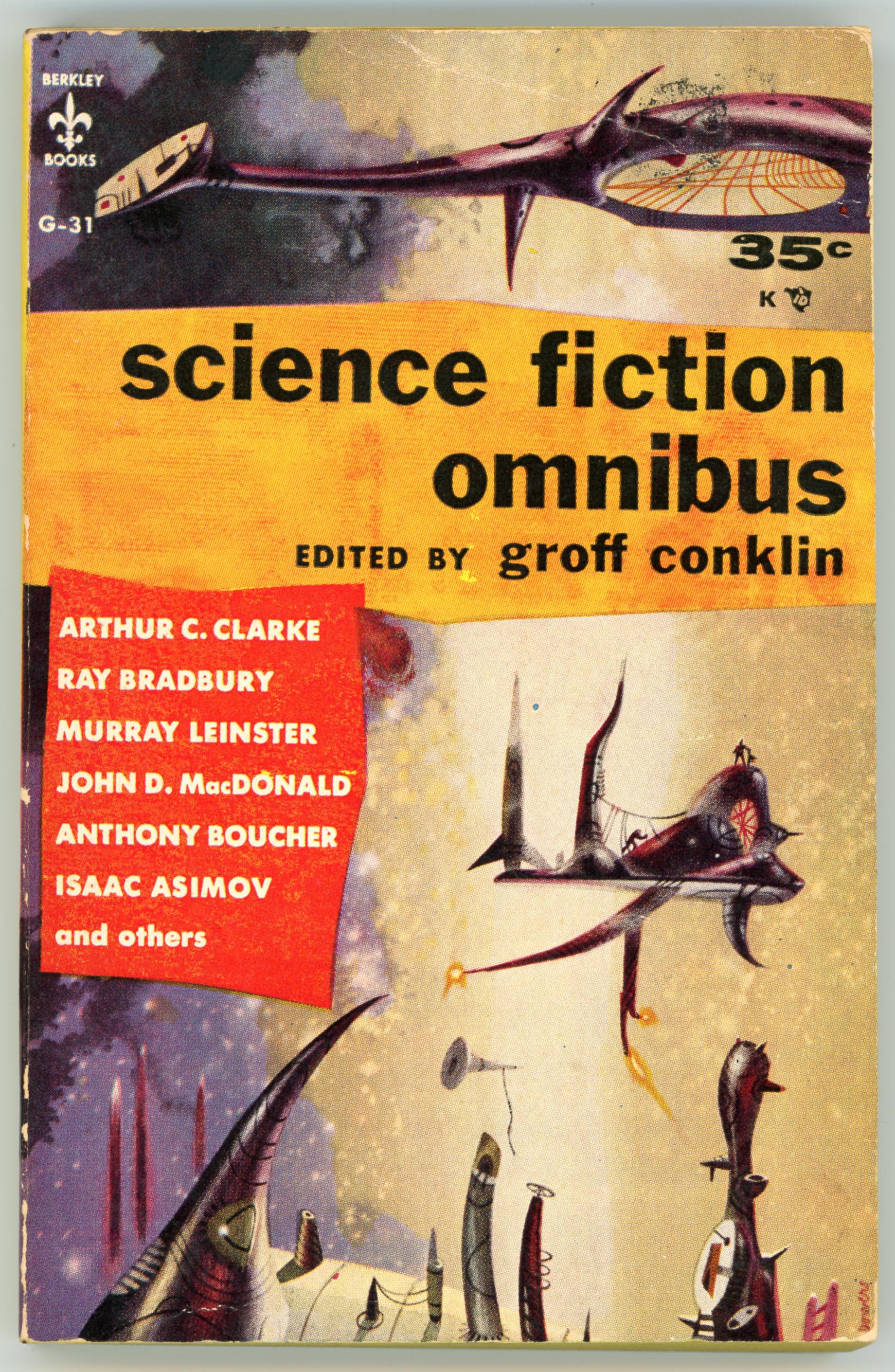

One of the over forty science fiction anthologies compiled by Groff Conklin, the Big Book of Science Fiction, while diminutive in physical size like other Berkley 50s paperbacks, features cover art by Richard Powers that’s arresting, entrancing, and positively l u m i n o u s.

Here it is:

Powers’ composition has qualities inherent to and epitomizing much of his work from that decade: A strange object of indefinite nature – metallic or organic? … machine or creature? – (creature!) … floats above an alien landscape, observing the scene beyond in perhaps detached amusement. A jagged horizon is set within the foreground, while in the far distance stand vaguely defined towers, perhaps rising from an alien metropolis hidden below. To the right, an immense spacecraft resembling an aircraft carrier is suspended in the background, with a spaceship about to blast from its deck. And above (you have to look closely) bursts of violet are scattered through the sky. They look like fireworks, but could they be missiles?

I really like this cover. Most of all, I like the way it’s backlit: Powers painted the sky shades of yellow, with wispy cirrus clouds scattered through, while having shadows in the foreground. It has a “feel” of impending twilight; of dusk; of arriving at a new world after an interminable journey, just as the planet’s sun is setting, to embark upon adventures yet unknown.

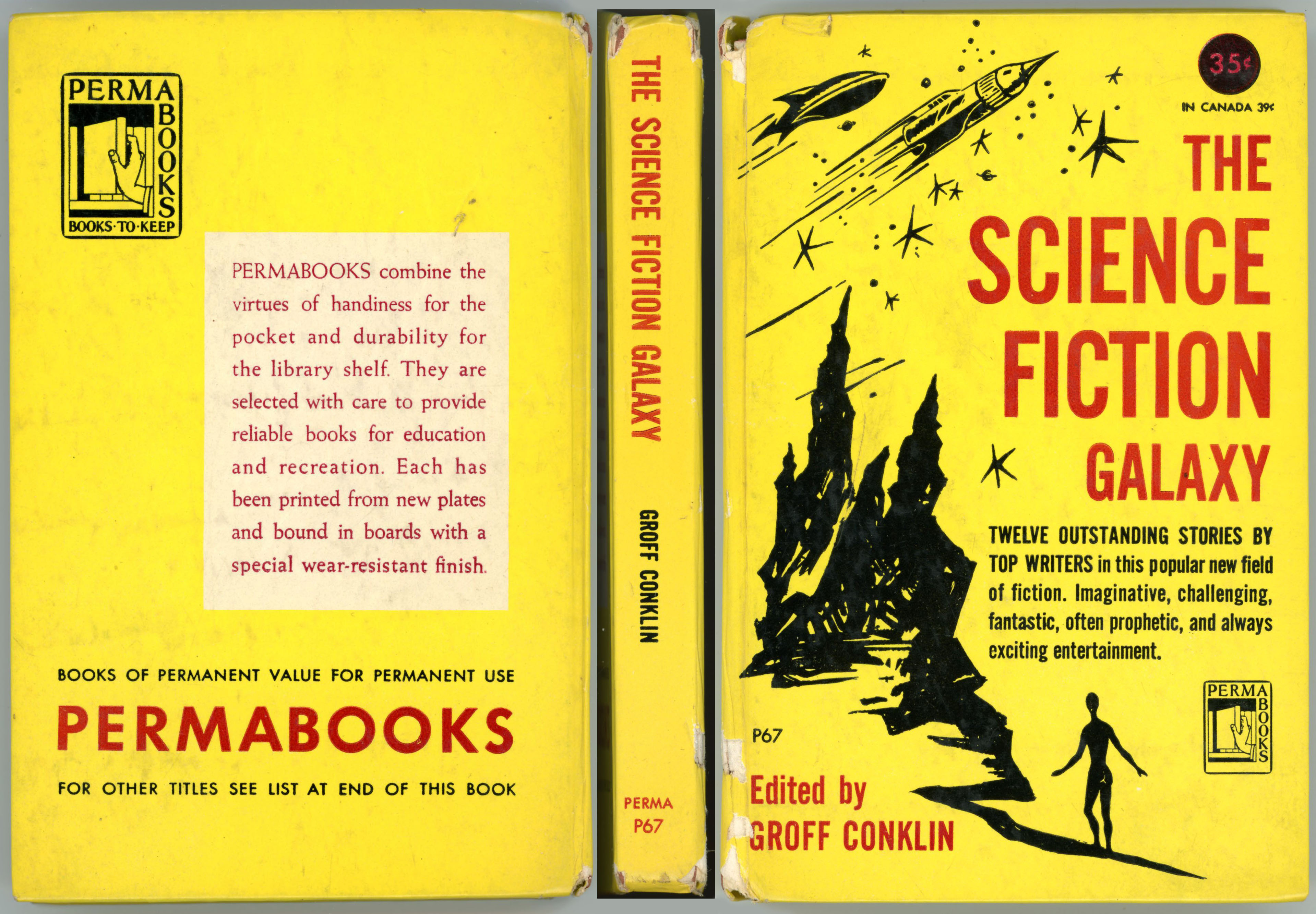

(For covers in a similar style, check out Crossroads in Time, Science Fiction Omnibus, and especially, A Treasury of Science Fiction, while for the inspiration behind the floating ship, take a look at A Suspension of Belief.)

For the purpose of this post, I thought I’d take this cover “One Step Beyond”. (Pun intended!) With that, I’ve edited the (halftone) image via Photoshop Elements, to remove chips, creases, dings, and tiny-yet-obviously out of place blobs of ink.

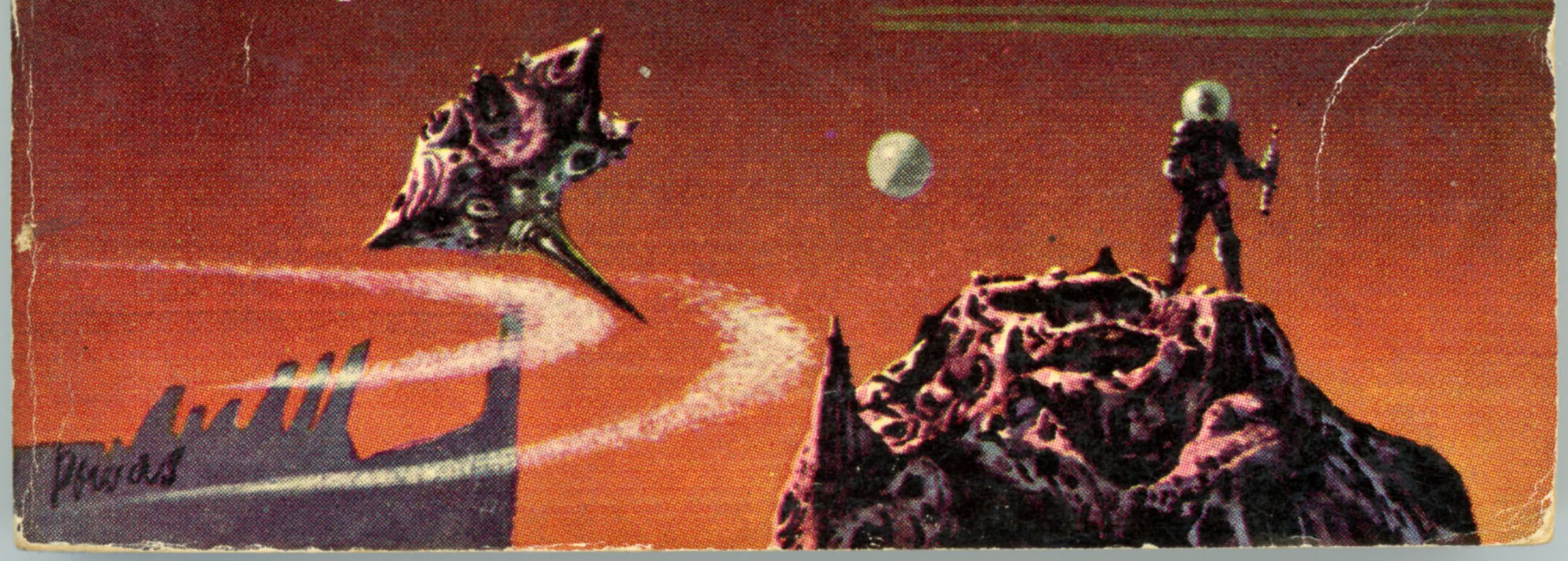

Here’s the resulting effort, which allows a greater appreciation of Powers’ work.

Remarkably, Powers’ original painting has survived! I found a great scan of it at Comic Art Fans, where it’s part of the John Davis & Kim Saxon Collection, which includes 45 works by Powers. Done in acrylics, it’s not that big: just 12 x 16 inches.

Here it is:

So, here’s the back cover, the text of which is representative of the current of techno-optimism inherent to – yet even by then waning from – science-fiction of the 1950s.

PREVIEW OF THE FUTURE AND ALL ITS WONDERS

In reading this book you will be transported into the far distant future, to the times inhabited by your remote descendants. You will visit worlds of super civilizations, travel between the stars, experience atomic power, see strange and marvelous inventions, witness the curious aliens from far-off planets.

Above all your imagination will soar above the petty anxieties of everyday life into the vast reaches of time and the universe where man and his problems are but a brief candle flame against the dark background of eternal night.

So, what’s in the book?

I’ve read five of the ten stories listed below: “Mewhu’s Jet”, “The Wings of Night”, “Arena”, “The Miniature”, and “The Only Thing We Learn”. Of the four, I would have to, and would easily, rank “Arena” as the best, regardless of having been penned typed eighty years ago. The plot is simple but very solid, the “world-building” – though very narrow – is very clear, while the pacing and tempo are maintained without letup throughout the entire story. “The Wings of Night”, while entirely passe in terms of scientific knowledge about the moon and extraterrestrial life, is a fine tale in a purely literary sense, and can still be appreciated in terms of its underlying social message. As for “The Only Thing We Learn”, while Cyril Kornbluth has been one of my favorite science fiction writers, well… The telling is fine, but the tale itself? Ho-hum.

“Desertion” (City series), by Clifford D. Simak, Astounding Science Fiction, November, 1944

“Mewhu’s Jet”, by Theodore Sturgeon, Astounding Science Fiction, November, 1946

“Nobody Saw the Ship”, by Murray Leinster, Future combined with Science Fiction Stories, May/June, 1950

“The Wings of Night”, by Lester del Rey, Astounding Science Fiction, March, 1942

“Arena”, by Fredric Brown, Astounding Science Fiction, June, 1944

“The Roger Bacon Formula”, by Fletcher Pratt, Amazing Stories, January, 1929

“Forever and the Earth”, by Ray Bradbury, Planet Stories, Spring, 1950

“The Miniature”, by John D. MacDonald, Super Science Stories, September, 1949

“Sanity”, by Fritz Leiber [as by Fritz Leiber, Jr.], Astounding Science Fiction, April, 1944

“The Only Thing We Learn”, by C. M. Kornbluth, Startling Stories, July, 1949

(Data from Internet Speculative Fiction Database)

And otherwise…

Groff Conklin, at…