While the Second World War air war over Europe – particularly that waged by the United States’ 8th and 15th Air Forces, and the Royal Air Force’s Bomber Command – has generated an abundance of memoirs, biographies, historical works, and, works of fiction in the seven-odd decades since that conflict ended, others theaters of World War Two military aviation have resulted in relatively fewer literary works. Perhaps this has been due to the sheer number of men and aircraft involved in military campaigns in the European Theater (at least in comparison to the Pacific and Asia); the precedence of the European Theater over Asia in terms of overall Allied and particularly American military strategy, and post-1945; the combined effect of both of these aspects of the war on cinematic and television entertainment, literature, popular culture, and publishing.

In cinematic terms, think of Daryl Zanuck’s 1949 film 12 O’clock High, itself inspired by and adapted from Bernie Lay, similarly-named 1948 novel, about the experiences of American airmen during the early phase of Eighth Air Force Operations in Europe, which itself inspired the similarly-named television series which ran on the ABC television network between 1964 and 1967. I don’t believe that the Army Air Force’s other numbered Air Forces – the Fifth; the Seventh; the Tenth; the Eleventh; the Thirteenth; even the European-based Ninth and Twelfth – were ever the objects of such attention. Not that it was not merited…

Still, accounts of the Pacific air war do exist, and are not really difficult to find. One such work is Ralph E. “Peppy” Blount’s 1984 We Band of Brothers, recounting Blount’s experiences as B-25 Mitchell strafer / attack-bomber pilot in the 501st Bomb Squadron of the Fifth Air Force’s 345th “Air Apache” Bomb Group. Not a purely straightforward chronological narrative of Blount’s experiences (though it is substantive in historical terms), the book accords notable attention to the reactions, feelings, and thoughts of Blount and his fellow 501st Bomb Squadron (and by extension, 345th Bomb Group airmen “in general”) airmen to the psychological stress of combat, and especially the loss of friends and comrades – of whom, given the duration and nature of the 345th’s war – there were very many.

The book’s cover, by Allain Hale, is shown below.

______________________________

______________________________

From Peppy’s book, here’s a photo of his crew:

“My original crew that was formed at Columbia Army Air Base, Columbia, S.C. This picture made in November, 1944. From left to right (standing): R.E. Peppy Blount pilot; P.O. “Arky” Vaughn, navigator; Harold Warnick, engineer-gunner, and squatting in front, Henry J. Kolodziejski, armorer-gunner and Joseph Zuber, radio-gunner. We were a B-25H crew which was the B-25 with the 75-millimeter cannon in the nose and no co-pilot. By the time we got overseas, a couple of months later, they had done away with the B-25H and replaced it with the B-25J which had fourteen forward firing .50 caliber machine guns and a co-pilot.”

“My original crew that was formed at Columbia Army Air Base, Columbia, S.C. This picture made in November, 1944. From left to right (standing): R.E. Peppy Blount pilot; P.O. “Arky” Vaughn, navigator; Harold Warnick, engineer-gunner, and squatting in front, Henry J. Kolodziejski, armorer-gunner and Joseph Zuber, radio-gunner. We were a B-25H crew which was the B-25 with the 75-millimeter cannon in the nose and no co-pilot. By the time we got overseas, a couple of months later, they had done away with the B-25H and replaced it with the B-25J which had fourteen forward firing .50 caliber machine guns and a co-pilot.”

______________________________

Coincidentally (or, perhaps not-so-coincidentally?!) Blount’s book was published in 1984, coincident with the release of Lawrence J. Hickey’s monumental Warpath Across the Pacific – The Illustrated History of the 345th Bombardment Group During World War II. Among its extensive photographic coverage of the airmen, aircraft, and combat missions of the Air Apaches, the book includes seven photographs pertaining to a mission by the 499th and 501st Bomb Squadrons to Saigon, French Indochina, on April 28, 1945, two of which – with transcribed caption – are shown below.

“The main target of the April 28, 1945, attack on Saigon, French Indochina, was this 500-ton freighter anchored in the river two miles east of the navy yard. The top photo was taken from #199 as 1 Lt. Ralph E. “Peppy” Blount of the 501st pulled up sharply just after dropping his three delay-fused 500-pound bombs. As shown below, two bombs were direct hits and a photo taker later from high altitude showed the ship over on its side in the water. Strangely, the ship, although clearly sunk, does not appear in wartime Japanese ship-loss records. The 499th and 501st Squadrons received Distinguished Unit Citations for this mission. (John C. Hanna Collection)”

“The main target of the April 28, 1945, attack on Saigon, French Indochina, was this 500-ton freighter anchored in the river two miles east of the navy yard. The top photo was taken from #199 as 1 Lt. Ralph E. “Peppy” Blount of the 501st pulled up sharply just after dropping his three delay-fused 500-pound bombs. As shown below, two bombs were direct hits and a photo taker later from high altitude showed the ship over on its side in the water. Strangely, the ship, although clearly sunk, does not appear in wartime Japanese ship-loss records. The 499th and 501st Squadrons received Distinguished Unit Citations for this mission. (John C. Hanna Collection)”

______________________________

______________________________

Warpath includes 53 color photographs of Air Apache B-25s and crewmen (from Kodachrome? – remember Kodachrome?!), and, 48 color profiles, as well as four paintings of Air Apache B-25s in combat – the profiles and paintings all by Steve W. Ferguson.

One of the paintings, depicting Peppy Blount’s strike against the un-named freighter, is reproduced below. It’s a superb piece of art, in terms of the use of color (the sky, transitioning from pale to darker blue going “upwards” is very realistic), getting the technical details of the B-25 “just right”, and visually depicting aspects of an anti-ship mission: the explosions of anti-aircraft fire, waterspouts from the surface of the Saigon River thrown up by shells aimed at the B-25, and the trails of tracer bullets from the B-25 and ship.

Most notable is the perspective and orientation from which the action is being viewed. The overwhelming majority of illustrations of aircraft – particularly military aircraft; especially military aircraft in flight; specifically military aircraft in combat – are rather “static” in appearance, showing aircraft as viewed from head-on, at a frontal angle, or viewed as if from another aircraft flying a parallel course. However, Ferguson’s painting shows B-25J #199 from a rear angle, as if the viewer is following the aircraft and being visually led into the image. This is enhanced by the single 500 pound bomb that has just left the plane, and the aircraft’s bank to the left.

______________________________

______________________________

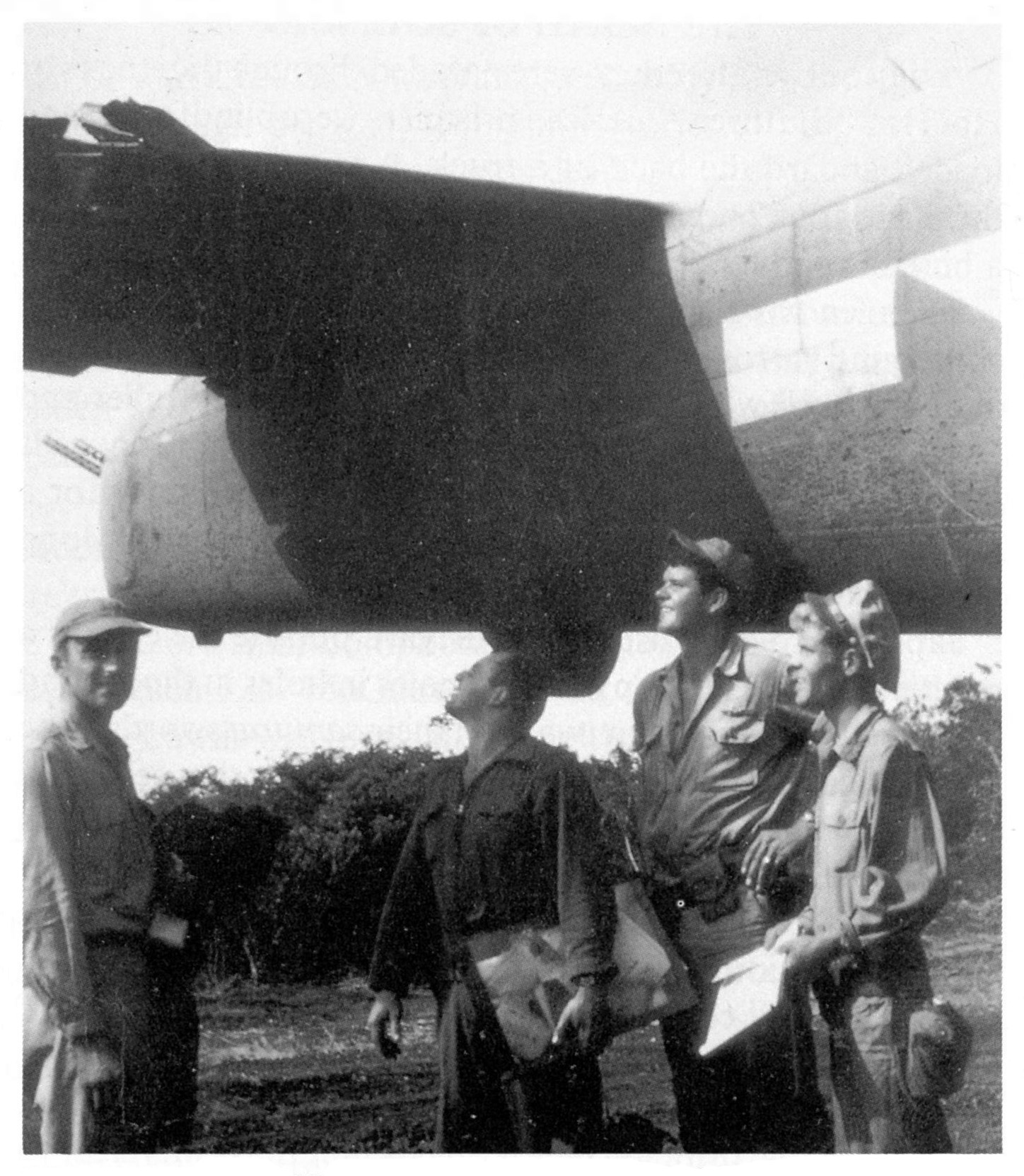

Peppy Blount’s B-25, damaged during the mission, is shown below.

“1 Lt. Ralph E. “Peppy” Blount, Jr. (second from right) and his crew looked over damaged to the 501st’s #199 after landing at Puerto Princesa, Palawan, from the Saigon mission. The damage to the horizontal stabilizer was caused by a collision with the mast of a large sailboat on the Dong Nai River. Blount was credited with inflicting fatal damaged to a large freighter which was sunk a few miles away in the Saigon River. The crewmen were from left: T/Sgt. Joseph F. Zuber, radio-gunner; 1 Lt. Nat M. Kenny, Jr., navigator; Blount, pilot; and 2 Lt. Kenneth R. Cronin, co-pilot. The engineer on the mission, T/Sgt. Harold E. Warnick, is not shown. (John C. Hanna Collection)”

“1 Lt. Ralph E. “Peppy” Blount, Jr. (second from right) and his crew looked over damaged to the 501st’s #199 after landing at Puerto Princesa, Palawan, from the Saigon mission. The damage to the horizontal stabilizer was caused by a collision with the mast of a large sailboat on the Dong Nai River. Blount was credited with inflicting fatal damaged to a large freighter which was sunk a few miles away in the Saigon River. The crewmen were from left: T/Sgt. Joseph F. Zuber, radio-gunner; 1 Lt. Nat M. Kenny, Jr., navigator; Blount, pilot; and 2 Lt. Kenneth R. Cronin, co-pilot. The engineer on the mission, T/Sgt. Harold E. Warnick, is not shown. (John C. Hanna Collection)”

______________________________

As recounted in Warpath, the Saigon mission cost the 501st three B-25s and crews. These men were:

B-25J 43-36173 (MACR 16178)

Pilot – 2 Lt. Vernon M. Townley, Jr.

Co-Pilot – F/O Hilbert E. Herbst

Bombardier / Navigator – 2 Lt. Robert L. Burnett

Flight Engineer / Gunner – Cpl. Harry Sabinash

Radio Operator / Gunner – Cpl. Seymour Schnier

B-25J 43-36020 – “Reina Del Pacifico” (MACR 16179)

Pilot – 2 Milton E. Esty

Co-Pilot – 2 Lt. Marlin E. Miller

Navigator – 1 Lt. Joseph M. Coyle

Flight Engineer / Gunner – Sgt. James L. Golightly

Radio Operator / Gunner –T/Sgt. Henry C. Wreden

B-25J 43-36041 – “Cactus Kitten” (MACR 16256)

Pilot – 2 Lt. Andrew J. Johnson

Co-Pilot – 2 Lt. Paul E. Langdon

Bombardier / Navigator – 2 Aubrey L. Stowell

Flight Engineer / Gunner – Sgt. Alfredo P. Parades

Radio Operator / Gunner – Cpl. Lester F. Williams

______________________________

Here is Steve Ferguson’s profile of un-nicknamed B-25J 43-36199 (#199).

From Warpath: “…this aircraft was a favorite of the irrepressible 1 Lt. Ralph E. “Peppy” Blount, who flew it on the April 28, 1945, raid on shipping at Saigon for which the Squadron received a Distinguished Unit Citation. Blount sank the principal target, a 5,800 ton freighter, and although badly damaged by AA, was attacking a second ship when he collided with its mast, breaking it off. He flew homeward for several miles with seven feet of it lodged in the horizontal stabilizer. The plane made the 700 miles back to base despite severe damage to one nacelle and the tail. … The crew of #199 on that mission was: Blount, pilot; 2 Lt. Kenneth R. Cronin, co-pilot; 1 Lt. Nat M. Kinney, Jr., navigator; T/Sgt. Joseph F. Zuber, radio operator – gunner, and T/Sgt. Harold E. Warnick, tail gunner.”

From Warpath: “…this aircraft was a favorite of the irrepressible 1 Lt. Ralph E. “Peppy” Blount, who flew it on the April 28, 1945, raid on shipping at Saigon for which the Squadron received a Distinguished Unit Citation. Blount sank the principal target, a 5,800 ton freighter, and although badly damaged by AA, was attacking a second ship when he collided with its mast, breaking it off. He flew homeward for several miles with seven feet of it lodged in the horizontal stabilizer. The plane made the 700 miles back to base despite severe damage to one nacelle and the tail. … The crew of #199 on that mission was: Blount, pilot; 2 Lt. Kenneth R. Cronin, co-pilot; 1 Lt. Nat M. Kinney, Jr., navigator; T/Sgt. Joseph F. Zuber, radio operator – gunner, and T/Sgt. Harold E. Warnick, tail gunner.”

______________________________

Artist Steve Ferguson’s biography, from the dust jacket of Warpath Across the Pacific.

______________________________

______________________________

Finally, a closing passage, presenting Peppy Blount’s memory of a friend, 1 Lt. Melvin R. Bell.

On February 20, 1945, Bell’s Mitchell (B-25J 44-29374; MACR 15334) was lost during the 345th’s mission to the marshaling yard at Kagi, Formosa, and along the western coast of the island. Among a group of seven 501st B-25s that were attempting to attack Chosu Airdrome (about forty miles south of Kagi), the right engine of Bell’s B-25 was knocked out by anti-aircraft fire. The 501st immediately left the target area and escorted Bell to an air-sea rescue point near North Island, where he ditched his B-25.

But, only two of Bell’s five crewmen (T/Sgt., Glenn C. Allen, and S/Sgt. George A. Harvey) returned. Bell, 2 Lt. Alvin G. McIver (copilot), 2 Lt. Robert L. Bacon (bombardier), and S/Sgt. Alphonse R. Ostachowicz (flight-enginner / gunner) did not survive the ditching.

As told by Peppy Blount:

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

“Have you heard anything from Thatcher and Bell?” I asked immediately.

“Not a thing –

but the squadron radio is monitoring the channel

and the moment we know anything, it’ll be reported here.

Where did you hit today?”

“We came across the target in a northeast to southwest pass,”

as I pointed to a large, aerial photo of the Jap air base we had hit only three hours before.

Following the debriefing I returned to my tent

and didn’t get the news about Bell until an hour later

when I met Thatcher coming from debriefing as I was going to chow.

“What happened to Bell?” I asked immediately

and the expression on Thatcher’s face told me the answer

without his having to speak a word.

“The Catalina Playmate got there in time, but it was no use,”

answered Thatcher.

“Bell simply could not hold his altitude on one engine and finally had to ditch her.

You know how rough that water was today and he went in pretty steep,

missed the top of the wave,

hit in the valley between two waves,

and that was it.

They didn’t have a chance, with surface winds of thirty-five miles an hour.

The ship nosed straight up,

the top turret came forward,

crushing the cockpit,

and the only survivors were the two men in the rear of the airplane,

the radio man and tail gunner.”

“Did he say anything else after I left?”

“You heard the last thing he said,” replied Thatcher,

“that it looked like this deal had turned to clabber!

Sounded just like him, didn’t it?

“Yeah! Just like him.”

I had lost my appetite.

His last words had been a beau geste benediction to an inevitable,

even expected,

plight that each of us would be in tomorrow – the day after – or next week.

Later than evening,

one by one,

we straggled into Bell’s tent until it was full.

Each of us wanted it to appear as if we had wandered in,

but each of us knew that it was on purpose,

and out of respect for a dear friend.

Ike Baker had already gathered his personal things to be sent to his family;

the remaining items of clothing and toiletries had disappeared among his friends

almost as quickly as they had been displayed,

including a month’s supply of Brown Mule plug chewing tobacco.

I wouldn’t have been surprised to have heard him observe:

Here I’m not dead more’n a couple of hours

and already you‘ve picked me clean, like a flock of buzzards!

Only an empty, lonesome bunk with mosquito netting,

a folded air mattress,

and some make-shift shelves behind the bunk that more nearly resembled an apple crate,

gave moot evidence of the absence of our friend.

Although the seven or eight of us who “just happened” to show up by accident

after chow that evening sat on every extra stool,

and overflowed on to his other tentmate’s sacks –

out of conscious respect,

not one sat on Bell’s empty bunk. (We Band of Brothers, pp. 257-258)

References

Hickey, Lawrence J., Warpath Across the Pacific – The Illustrated History of the 345th Bombardment Group During World War II, International Research and Publishing Corporation, Boulder, Co., 1984

Blount, Ralph E. Peppy, We Band of Brothers, Eakin Press, Austin, Tx., 1984

January, 2019