Well!

Sometimes it’s hard to figure out how to begin a blog post.

After all, what can possibly be said about L. Sprague de Camp’s 1951 science-fiction novel “Rogue Queen”?!

Except perhaps…

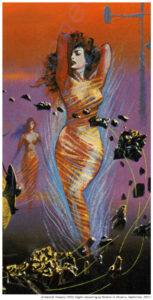

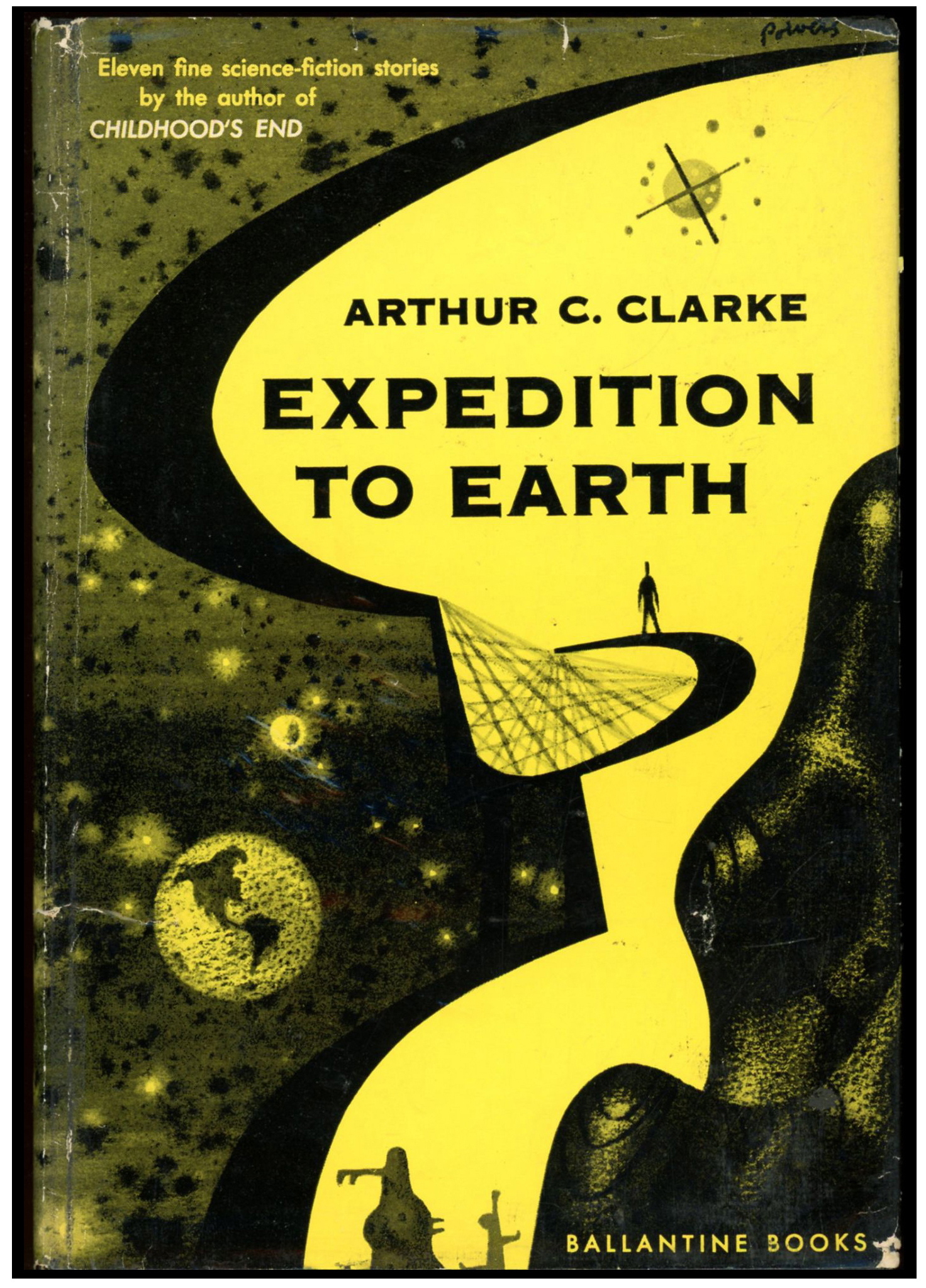

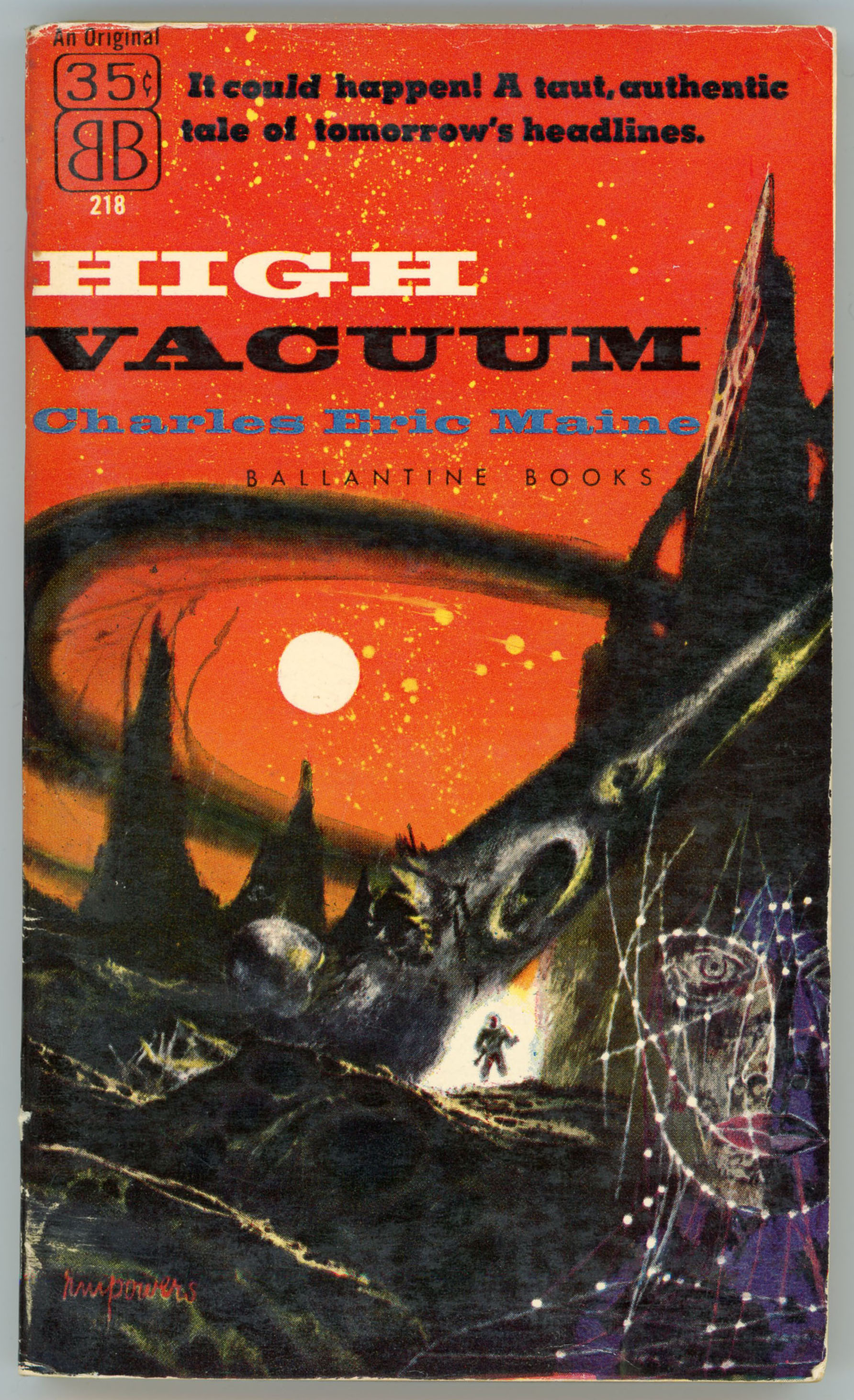

In the same way that readers and reviewers can have markedly different interpretations of the same work of literature, so can artists. Such is so for successive editions of L. Sprague de Camp’s novel Rogue Queen, which was first published by Doubleday in 1951 with a cover by Richard Powers, and was most recently reprinted in 2014. Neither abstract nor ambiguous like much of his later body of work, his painting – while stylized – is directly representational of an aspect of the book’s plot, which pertains to humanoid bipeds (biologically, very much like us) of the planet Ormazd, the organization of whose civilization is analogous to that of social insects: the bees, of our Earth. Powers’ cover – the fourth work of his massive oeuvre – combines central elements of de Camp’s novel – a revolt by the female workers of Ormazd (they do look a little insect-like, don’t they, what with the Vulcan ears and eyebrows?!), and, the influence of explorers from Earth (notice the helicopter and spaceship?), set against very “earthy” tones of orange and brown.

(This example is via L.W. Currey booksellers.)

I don’t know the specific month when the book was released, but a very brief review by “A.B.” (Alfred Bester?) appeared in The New York Times Book Review on July 29, 1951, under the title “Men of the Hive”, where it’s accompanied by reviews of Groff Conklin’s Possible World of Science Fiction, and, Jack Williamson’s Dragons Island, all enlivened by an illustration of fluffy extraterrestrial something-or-others on an alien planetscape. Though I don’t know the time-frame, it seems that the Times Book Review featured numerous such science-fiction mini-reviews during the mid-1950s, perhaps attributable to science-fiction by then – post WW II – finally moving into the mainstream of literary acceptability.

ROGUE QUEEN, By L. Sprague de Camp. 222 pp. New York: Doubleday & Co., $2.75.

MR. DE CAMP has made up for the lapse of his colleagues by producing a science-fiction narrative which is entirely about sex, and, surprisingly, non-pornographic. Imagine a civilization of mammalian bipeds not unlike us who have developed a society like that of the bees, in which all males are drones (that is, stallions) and all females, save for a few hypersexed queens, are de-sexed workers. Then let an expedition from Earth accidentally foster the concept of romantic love, and you have that rarest of collector’s items: a completely new science-fiction plot. A.B.

The Author: L. Sprague de Camp

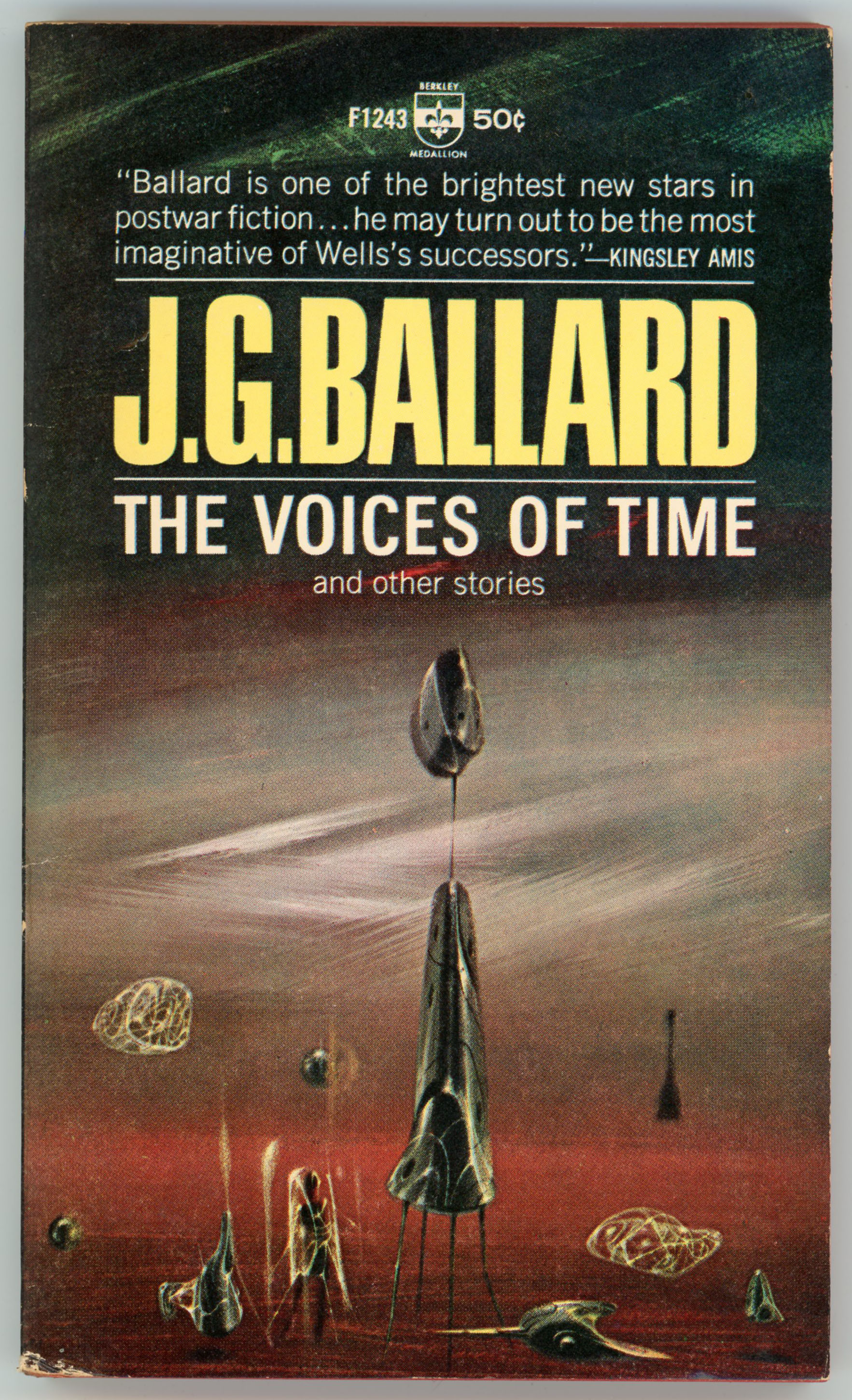

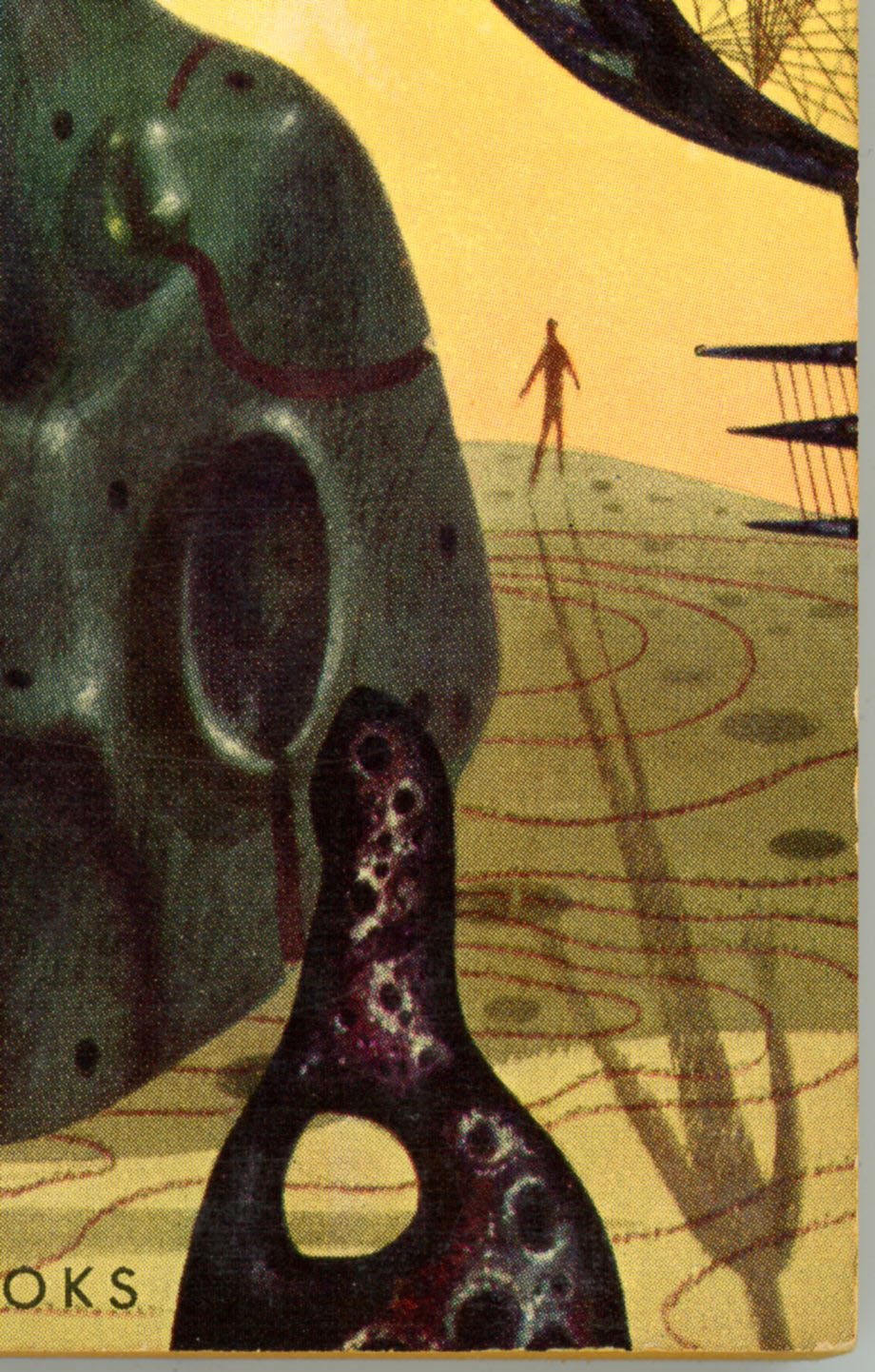

And now, for something different. Er, completely different. Um, dramatically different: Ed Emshwiller’s startling take on Iroedh, the protagonist of de Camp’s story. While this cover shares the elements of Powers’ painting – female workers in revolt, earth spaceship, and spacey planet a-floating-in-the-sky – Ed Emshwiller really pushed the boundaries of 1950s paperback science fiction art in his depiction of the novel’s heroine. The sunset backlighting, purple cast to her skin, and yellow highlights lend a lurid and near-photographic mood to the cover.

As for the novel itself? I confess!… I’ve not actually read it (yet), ironically due to the near-mint condition and fragility of this copy. However, it does have two overarching similarities with a subsequent 1950s science-fiction novel: Philip José Farmer’s The Lovers, which first appeared in the August, 1952 issue of Startling Stories: A planet inhabited by a human – or near-human (spoiler alert!) – species which has complete – or near-complete – physical compatibility with humans, and, the result of human interaction with that alien species.

Given the timing of release of the two novels, I wonder – as I type this post – if de Camp’s book in any way influenced Farmer’s effort one year later. The answer to that question I do not know. What I do know is that despite the superficial parallels in plot of the two books, the The Lovers is (well, admittedly only compared with my reading about and not of Rogue Queen) an entirely different tale, the tone, mood, theme, and weighty conclusion of which are completely serious, addressing questions about the nature of love (not solely physical or erotic love, though those certainly are central to the story), society, and religion. In the hands of a skilled producer, director, and team of writers, The Lovers has more than enough substance to serve as the basis for a feature film, or even a miniseries. Would that this should happen!

As for Rogue Queen, the nature of de Camp’s book is well summarized in the following two blurbs from the flyleaf:

On outer flyleaf…

HE BROUGHT HER

A NEW KIND OF LOVE

This oddly alluring creature wouldn’t have made a bad-looking girl among human females – if your tastes run to pink six-footers with cat’s eyes! But being a neuter-female on the strange planet Ormazd, Iroedh had a lot to learn about the pleasures of love – and sex!

When Dr. Winston Bloch and his party arrived in their sky ship, Iroedh’s first duty as a loyal neuter worker was to line him up on her side in the planet’s inter-Community war.

But Iroedh was strangely (and illicitly) in love with the drone Antis, whose sole function was to fertilize the egg-laying Queen. Since the Earth-men had the power to save Antis from imminent liquidation, Iroedh had no choice but to join them and become an outlaw – a rogue.

Then she learned the amazing secrets of sex and fertility, how a neuter-worker can be transformed – in mind and body – into a flesh-and-blood functional female.

She and Antis take it from there, gaily changing the whole structure of Ormazdian life with the slogan –

“EVERY WORKER A QUEEN –

A QUEEN FOR EVERY DRONE!”

I found this version of Emshwiller’s cover art for Rogue Queen – sans text and title – “somewhere” in the digital world.

On inner flyleaf…

THEY INHABITED A STRANGE WORLD

Iroedh was a sexless worker in the far-off planet of Ormazd – but hunger made her a woman! Antis was a drone, the professional consort of a Queen – but love stirred strange emotions in his heart. Their extraordinary love affair turned the planet topsy-turvy after they met.

VISITORS FROM THE EARTH

Doctor Winston Bloch, who had sex problems of his own, and beautiful Barbe Dulac, who gave Iroedh her first abnormal (for her!) lessons in love.

The lovers learned many strange things from each other in the course of their adventures, and they met many strange beings, such as Wythias, the outlaw drone; Gildakk, the phony Oracle; and Queens Intar and Estir, who fought a duel for the succession to the throne only to lose it in the end to a new and exciting

ROGUE QUEEN

On back cover…

SHE WAS BEAUTIFUL – BUT SHE WASN’T A WOMAN

At least she wasn’t a complete woman.

But in her heart there was love for the drone Antis – strange love, strictly unlawful and delightfully unconquerable. At first it made her an outcast. Later the Earthman taught her the facts of full womanhood, and manhood too – and her body responded in strangle pleasing fashion.

Like all workers on the distant planet Ormazd, she had been a neuter-female, forced to leave the business of love – and sex! – to the Queens and the drones. Now armed with new knowledge, she opens thrilling possibilities for all the people of the planet, and proves – most divertingly – that love conquers all even in the heart of a

ROGUE

QUEEN

Harrrumphhh!

We’ll conclude right where we began.

In light of the above, there’s only one thing to be said about all this!

A Roguish Queen, at…