Here’s Elaine Feinstein’s New York Times’ review of Vasily Grossman’s magnum opus Life and Fate, as published by Collins Harvill in 1985. I believe that the Collins’ edition of the book was the work’s first English-language publication.

Notice that Feinstein doesn’t address aspects of the work as literature (all books, regardless of the author, have their merits, idosyncracies, and foibles), instead focusing on the novel more in terms of its historical context – “history” history, and, literary history – and the characters who appear in its many pages.

The photograph which appears in this post – certainly not in the original book review! – provides an emblematic view of Grossman during his service as a correspondent in the Soviet Army. Though I possess no information about the picture’s date and location, the demolished buildings in the background – on one of which appears a sign ending with the letters “…rie, 10” suggest that the photo was taken in Germany. The image is evidently one of a set of two (or more?) such photos taken at the same moment; you can view its counterpart at my blog post for H.T. Willett’s 1985 review of Life and Fate.

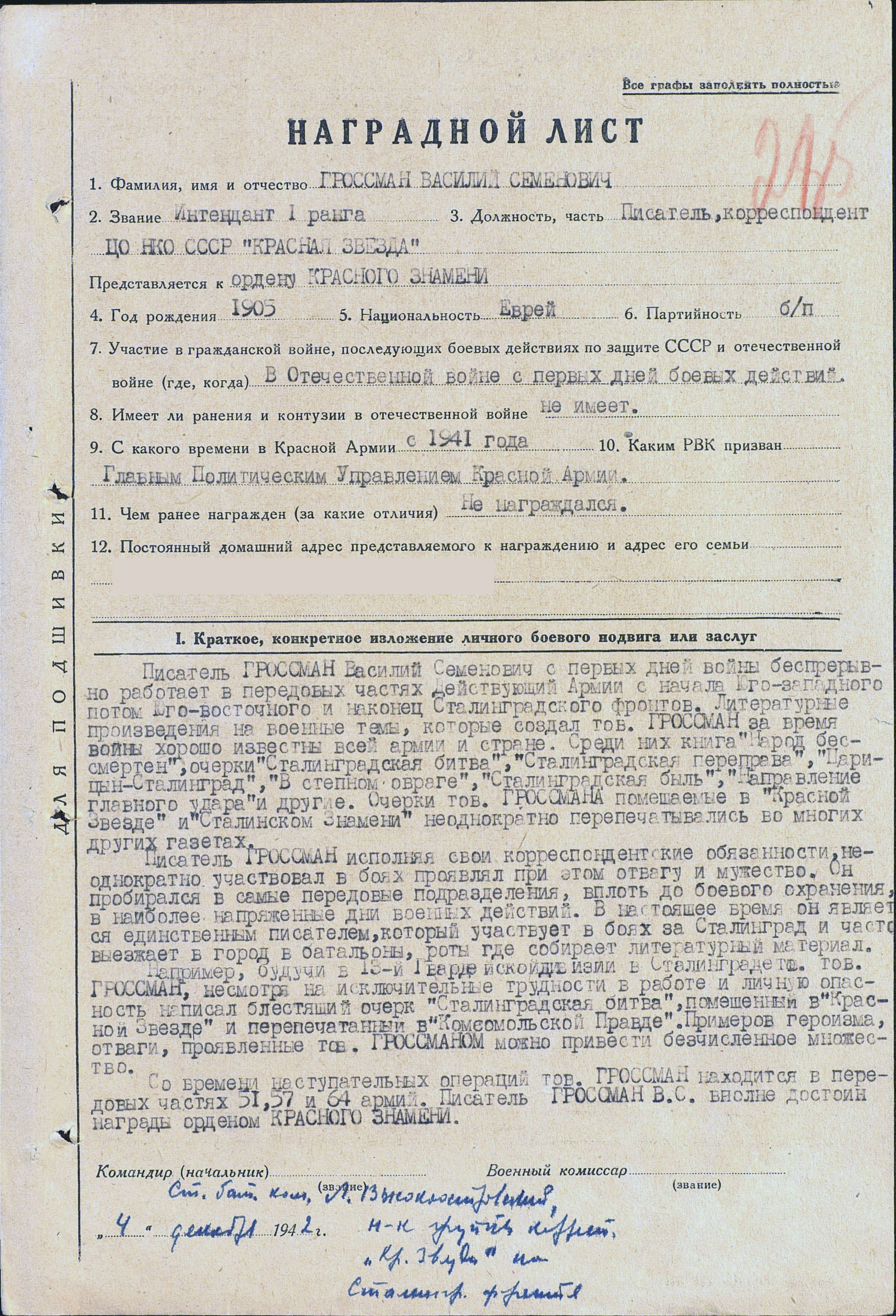

In terms of Grossman’s military service, you may find interest in his military award citation for The Order of the Red Star (Ordenu Krasnaya Zvezda – Ордену Красная Звезда), dated 9 December 1942, which is available at Heroic Feats of the People (Podvig Naroda- Подвиг Народа). This document specifically mentions Grossman’s works “The People are Immortal,” “The Battle of Stalingrad”, “Stalingrad Crossing”, and “Stalingrad Story”.

The citation also appears below:

________________________________________

________________________________________

From Workplace and Battlefield

Elaine Feinstein

VASILY GROSSMAN

Life and Fate

Translated by Robert Chandler

880pp. Collins. £15.

0002614545

November 22, 1985

(Photograph accompanying Alexander Anichkin’s blog post of January 31, 2011 “Grossman’s Life and Fate to be Serialised by the BBC“, at Tetradki – A Russian Review of Books.)

(Photograph accompanying Alexander Anichkin’s blog post of January 31, 2011 “Grossman’s Life and Fate to be Serialised by the BBC“, at Tetradki – A Russian Review of Books.)

Through the narrative of Evgenia Ginzburg, the camp stories of Shalamov, and the memoirs of Nadezhda Mandelstam, we have learnt a good deal of what it meant to live in Stalin’s Russia during the years, of the Terror; but the Great Patriotic War, in which Hitler was turned back at Stalingrad, has largely remained sacred in our imagination. The books in which .Solzhenitsyn attempts most stridently to persuade us that the fight against Communism was, even at that point, more vital to our civilization than the struggle against Nazism, have never seemed to be his best. This extraordinary novel by Vasily Grossman is set precisely at the historical moment when the, outcome of the house-to-house fighting, at the height of the struggle, is still in doubt. And as the book fans out to follow the fortunes of an extended family network, it poses a terrible question. Could any military victory mean much, given what we now know men and women are capable of doing to one another? It is important to understand that this question is asked by a man altogether inside the Soviet world; a writer discovered by Gorky, working alongside Ehrenburg; a man who understands contemporary science well enough to set a figure recalling Lev Davidovich Landau, a genius of theoretical physics, at the heart of his book; a man who came to think of himself as a Jew only with the death of his mother at German hands.

As it stands, the book is a sprawling giant, which might well have been re-worked by the author if his manuscripts had not been confiscated when he submitted the novel for publication. (He died in 1964.) It remains as remarkable a document of the conflicts of daily working lives under political and moral stress as we are likely to be given. Grossman is a writer untouched by Modernism. Essentially (since Socialist Realism always took the nineteenth-century novel as its pattern) he invites comparison with Tolstoy throughout his book. Unlike most writers who Warrant that comparison through the sheer scope of their material, Grossman occasionally shows a delicacy of local observation and a quality of insight which genuinely recall War and Peace. There is a particular freshness in the letter from Anna Semyovna, dismissed with other Jews from her hospital post and herded into a ghetto, hurt most by the thought of ending her life far away from her son. Not every character that enters the battlefield has the same vitality. The strength of Grossman’s work, however (and this is an overwhelmingly powerful novel), lies in his understanding both the multiplicity of human bitterness and the occasional miracles of kindness.

At the centre of the book, the mathematician Viktor Shtrum (to whom Grossman has given much of his own experience) lives with his wife Lyudmila. He cannot help reproaching her for her coldness towards his Jewish mother, just as she cannot help resenting his indifference towards her son from an earlier marriage. Lyudmila’s bitterness is fixed forever when her son dies at the front on a surgeon’s table. When she meets the surgeon, she recognizes his need for the comfort of her forgiveness. The sensitivity of such understanding is never extended to her husband.

For all his brilliance, Shtrum is at risk inside the laboratory; his wife refuses to share either his triumphs or his humiliations. When he is emboldened by nomination for a Stalin Prize to telephone a superior who usually ignores him, only to find he has been excluded from an evening entertainment, she taunts him with having got off on the wrong foot. And when he is explicitly accused of “dragging Science into a swamp of Talmudic abstractions”, the only person he can turn to is his colleague Chepyzhin, a character clearly based on the Cambridge-trained physicist, Kapitza, who refused to take part in any research relating to nuclear fission.

Chepyzhin’s grounds for such a refusal, in Grossman’s interpretation, go to the heart of human weakness. Viktor’s colleagues are not wicked or stupid, but they cannot be trusted. As Chepyzhin puts it: “You said yourself that man is not yet kind enough or wise enough to lead a rational life.” Of the many memorable episodes, few are more moving than the sudden intimacy of conversation between Shtrum and Chepyzhin, two men who take the risk of trusting one another and thereafter talk as greedily as “an invalid who can think of nothing but his illness”.

Not everyone is so fortunate. Betrayal is commonplace and there is always guilt. Mostovskoy, an Old Communist in a German POW camp, recognizes his own features in the face of his weary interrogator; and another Old Comrade discovers, in the Lubyanka, that innocence is no defence against torture. Grossman puts his deepest hopes into the mouth of an unhinged holy fool, Ikonnikov, who is executed because he refuses to take part in building an extermination camp. Grossman’s triumph is to make it seem irrelevant which monstrous State demanded that he should do so.”

Suggested Readings

Aciman, Alexander, Book Review: Vasily Grossman, the Great Forgotten Soviet Jewish Literary Genius of Exile and Betrayal, Lives Inside Us All, Tablet, October 23, 2017

Capshaw, Ron, The Scroll: The Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee Was Created to Document the Crimes of Nazism Before They Were Murdered by Communists – For the crime of acknowledging Jewish identity, the committee’s members were killed in a Stalinist pogrom, Tablet, November 29, 2018

Epstein, Joseph, The Achievement of Vasily Grossman – Was he the greatest writer of the past century?, Commentary, May, 2019

Eskin, Blake, Book Review: Eyewitness – A collection of Vasily Grossman’s shorter work offers a chance to reassess the Soviet master’s life and legacy. A conversation with Grossman translator Robert Chandler, Tablet, December 8, 2010

Kirsch, Adam, Book Review: No Exit: Life and Fate, Vasily Grossman’s indispensable account of the horrors of Stalinism and the Holocaust, puts Jewishness at the heart of the 20th century, Tablet, November 30, 2011

Taubman, William, Book Review: Life and Fate: A biography of Vasiliy Grossman, the Soviet writer whose masterpiece compared Stalin’s regime to Hitler’s, The New York Times Book Review, p. 16, July 14, 2019

Vapnyar, Lara, Book Review: Dispatches – How World War II turned a Soviet loyalist into a dissident novelist. Plus: An audio interview with the editor of A Writer at War, Tablet, January 30, 2006