Not long after the appearance of Elaine Feinstein’s review of Life and Fate, the novel was reviewed by H.T. Willetts – albeit, I don’t know the name of the publication in which this review actually appeared. (Veritably: Oops!) Mr. Willetts’ review also pertained to the Collins Harvill’ edition of the book.

Like Elaine Feinstein, Mr. Willetts’ focuses on the historical, social, and political context of the work’s creation and eventual publication, while taking special note of the personal and moral quandaries faced by the novel’s central characters, particularly the physicist Viktor Shtrum. He also notes how Grossman combines individuation of his protagonists with a multi-faceted depiction of (for instance) the battle for Stalingrad.

The photograph which appears in this post – not from Willett’s original review! – provides a good view of Grossman while serving as a correspondent in the Soviet Army. Though I have no information about the date and location of the image, the demolished buildings behind in the background- one of which carries a sign ending in the letters “…rie, 10” suggest that the photo was taken within Germany in 1945. The image is evidently one of a set of two (or more?) such photos taken at the same moment; you can view its counterpart at my blog post for Elaine Feinstein’s 1985 review of Life and Fate.

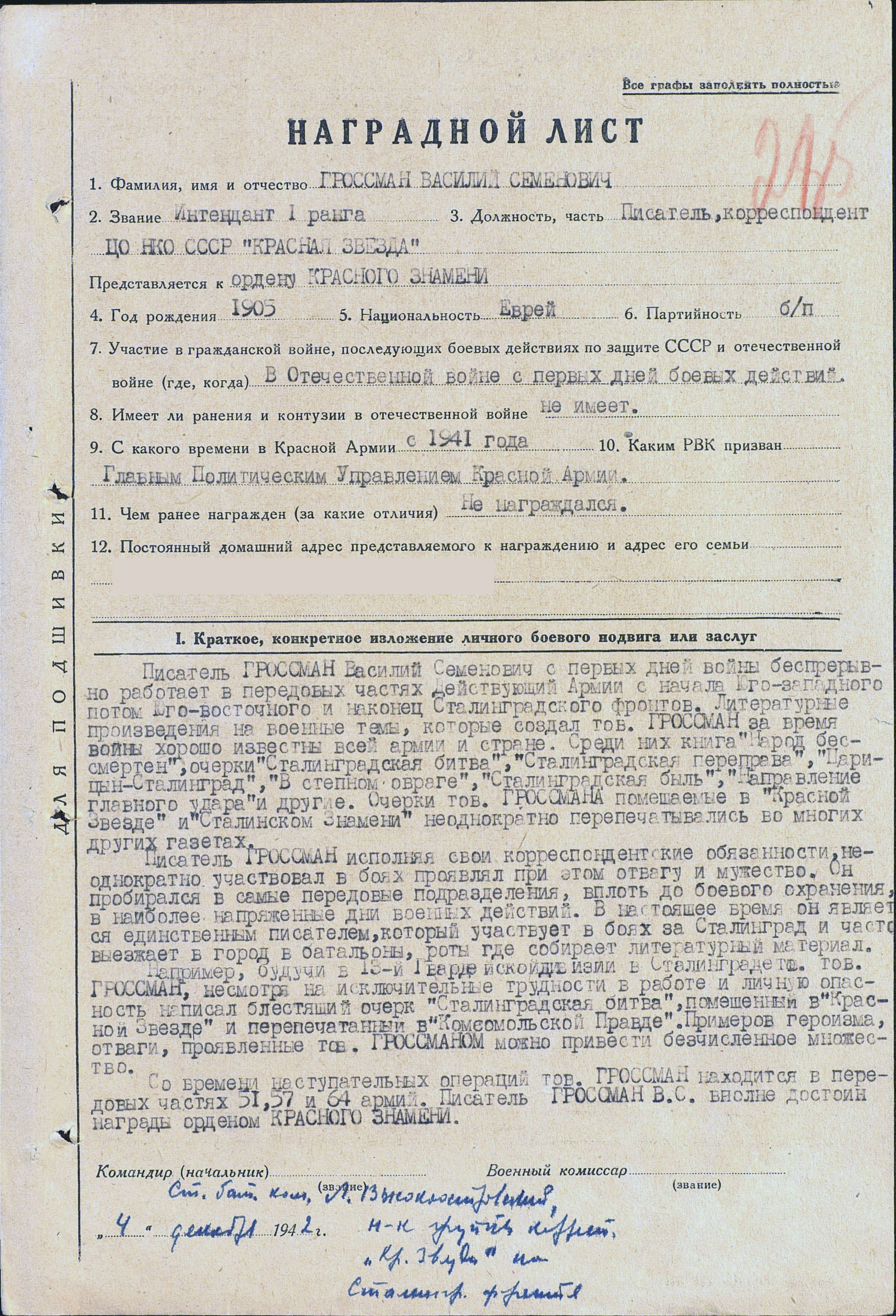

You may find interest in Grossman’s military award citation for The Order of the Red Star (Ordenu Krasnaya Zvezda – Ордену Красная Звезда), dated 9 December 1942, which is available at Heroic Feats of the People (Podvig Naroda- Подвиг Народа). This citation specifically mentions Grossman’s works “The People are Immortal,” “The Battle of Stalingrad”, “Stalingrad Crossing”, and “Stalingrad Story”.

Here’s the citation:

________________________________________

________________________________________

Overwhelming images of war

FICTION

H.T. Willetts

LIFE AND FATE By Vasily Grossman

Translated by Robert Chandler

Collins Harvill. £15

December 19, 1985

(Photograph accompanying Zelda Gamson’s essay of May 23, 2015 “The Life and Fate of Vasily Grossman“, at Jewish Currents.)

(Photograph accompanying Zelda Gamson’s essay of May 23, 2015 “The Life and Fate of Vasily Grossman“, at Jewish Currents.)

Life and Fate is the richest and most vivid account to be found of what the Second World War meant to the Soviet Union. Like all Soviet “epics”, ‘it is a mosaic – but not a bitter one. Grossman does not, as Ehrenburg did in the thirties, drag in new characters and invent gratuitous episodes because he cannot keep the story going. His characters are all connected, closely or by a long and intricate chain of circumstances, with the central figures, the Shaposhnikov sisters: we meet husbands, ex-husbands, children, ex-lovers … but also the politicos and commanders on whom the fate of their kin and friends depends … and the German officers and epauletted torturers who have many of their kin and friends under their paws. The scene shifts, back and forth, rapidly, but never confusingly, from the Stalingrad front to the reserve armies in the rear, to the evacuees in Kuibyshev, to those privileged to return from Kuibyshev to Moscow, to a German POW camp, to a Jewish ghetto, a Jewish column en route from the death camps, to Auschwitz, even, for a brief glimpse, to a frightened Hitler at his field HQ after the Stalingrad reversal.

Places are as solidly realized as people – above all war-shattered Stalingrad (Grossman was there throughout as a war correspondent). I shall never forget this utterly convincing and startlingly vivid picture of the (semi-barbaric) life of soldiers and workers among the rubble and the wrecked machines. We attend conferences at HQs (even Army HQs, with unloving portrayals of famous generals like Chuikov and Eremenko), but military operations are seen mostly at micro-level: from the snipers’ outposts, or the forward tanks in the great counterattack – the only vantage points from which the realities of war can be felt. In another extraordinary feat of descriptive writing the construction and equipment of Auschwitz are described in careful, dispassionate detail, as though what was before us was the building of a canning plant in a very superior Soviet “production novel” of the thirties. The effect is flesh-creeping – and the climax, with the plant in use, and its operatives individualized, is overwhelmingly macabre.

The novel owes much of its tragic power to Grossman’s understanding of the ambivalence of patriotism. He sees many resemblances between Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany – and the most fateful was the capture and perversion of patriotic feeling by unscrupulous politicians. This theme is fascinatingly developed in his account of relations between the real soldiers and the political officers at the front. Here is the supreme irony: the Soviet regime survived because it let patriotism, simple Russian patriotism, have its head – then took control of it, and perverted it to other purposes. No book except Gulag has so enlarged my understanding of the way in which the regime distorts ordinary human relations – and the extent to which the regime was produced and is sustained by banal and venal human selfishness and callousness.

A by-product of Stalinist nationalism was the anti-semitism which received tacit, then more explicit official encouragement as the war drew to its end. It is in this context that we see Grossman’s greatest triumph over the temptations of his material. The atomic physicist, Shtrum is almost destroyed by a tidal wave of official anti-semitism, but plucked to safety by Stalin in person, who knows that atomic physics and anti-semitism both have their (limited) uses. Grossman handles Shtrum’s story with irony and compassion. Nobly, even self-destructively (to his family’s exasperation), defiant while he is persecuted, Shtrum, once “vindicated”, tries to shut his mind to doubt and enjoy his success.

No more powerful war novel has come from any country for many years past.

Suggested Readings

Aciman, Alexander, Book Review: Vasily Grossman, the Great Forgotten Soviet Jewish Literary Genius of Exile and Betrayal, Lives Inside Us All, Tablet, October 23, 2017

Capshaw, Ron, The Scroll: The Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee Was Created to Document the Crimes of Nazism Before They Were Murdered by Communists – For the crime of acknowledging Jewish identity, the committee’s members were killed in a Stalinist pogrom, Tablet, November 29, 2018

Epstein, Joseph, The Achievement of Vasily Grossman – Was he the greatest writer of the past century?, Commentary, May, 2019

Eskin, Blake, Book Review: Eyewitness – A collection of Vasily Grossman’s shorter work offers a chance to reassess the Soviet master’s life and legacy. A conversation with Grossman translator Robert Chandler, Tablet, December 8, 2010

Kirsch, Adam, Book Review: No Exit: Life and Fate, Vasily Grossman’s indispensable account of the horrors of Stalinism and the Holocaust, puts Jewishness at the heart of the 20th century, Tablet, November 30, 2011

Taubman, William, Book Review: Life and Fate: A biography of Vasiliy Grossman, the Soviet writer whose masterpiece compared Stalin’s regime to Hitler’s, The New York Times Book Review, p. 16, July 14, 2019

Vapnyar, Lara, Book Review: Dispatches – How World War II turned a Soviet loyalist into a dissident novelist. Plus: An audio interview with the editor of A Writer at War, Tablet, January 30, 2006