Is art a science? Perhaps.

Is science an art? Maybe.

The two in combination made a notable appearance in Astounding Science Fiction in 1939, in the form of two articles (and letters in reply) concerning the technology and tactics of war in space. This material is fascinating from the perspectives of culture and history, and a few years back, I posted transcripts of and commentary about these articles at one of my brother blogs, thepastpresented.

Though that blog isn’t presently “up and running” (oh, well!) I’m recreating these posts here at WordsEnvisioned, because they so nicely compliment the themes of this blog, which include science fiction, pulp magazines, and – to a greater or lesser or uncertain extent! – technology and military history, as displayed in book and magazine art.

So, “this” is the first of these three posts: Covering Willy Ley’s article “Space War” in the August, 1939, issue of Astounding. Enjoy!

________________________________________

________________________________________

So.

…lately, I’ve been perusing my collection of science-fiction pulps – Astounding Science Fiction; Analog; Galaxy Science Fiction; The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction; Startling Stories; Beyond Fantasy-Fiction, and more – admiring cover and interior art; admiring the primacy of pigment on paper versus the stale purity of pixels; and especially appreciating the contrast between the first time I read “such and such” story in a paperback anthology; say, Fredric Brown’s “Arena“, in Volume I of The Science Fiction Hall of Fame – versus that tale in its original incarnation in the June, 1944 issue of Astounding.

It seems.

…that the very contrast between things; events; images – as we remember them – and as they actually are, can be of deeper impact that those very “things” themselves.

And.

…that “contrast” can easily extend to the taken-for-granted realms of ideas or technology. In the realm of science fiction, striking examples of this – in juxtaposition to the “world” of the 2020s – appeared in Astounding Science Fiction in August and November of 1939, in the form of articles by Willy Ley and Malcolm Jameson. Respectively entitled “Space War” and “Space War Tactics”, both authors presented analyses of how battles between spacecraft (specifically, ship-versus-ship combat) would actually be conducted. It’s particularly fascinating to read these articles in the context of science and technology of the late 1930s, versus how such combat would be imagined in subsequent decades.

Well.

…I enjoyed reading these articles. And, in light of contemporary and ongoing news about “space” having become a realm of military activity, at a level even beyond what’s transpired since the early 1960s, I thought you’d appreciate them, too.

Anyway.

….what I’ve done is fully transcribe both articles as separate posts, as they originally appeared in Astounding. The posts include the illustrations and captions that appeared in the original articles, to which I’ve tossed in some videos, links to additional sources of information, and biographical information about one author – Malcolm Jameson – in particular. In the latter article (in the next post), velocities listed in the text have been recalculated as miles (statue miles) and kilometers per hour.

Purposefully.

…These posts aren’t intended to critique the technological validity of the analyses and conclusions arrived at by Ley and Jameson. Rather, they’re instead to open a window upon the intellectual, scientific, and even social “flavor” of the times. While some of the authors’ analyses and conclusions will be incorrect, quaint, or passe in light of scientific and technological developments that have occurred in the eight decades since their publication, I can’t help but wonder about the relevance and validity of at least some of their insights, in terms of general concepts about kinetic (projectile) weapons versus “rays”, “beams”, or, aspects of identification, tracking, and aiming by opposing spacecraft. So, each article is preceded by a summary of its central points, with the most notable passages of the text being italicized and in dark red text, like these last fourteen words in this sentence. Both posts conclude with links to videos covering spacecraft-versus-spacecraft battles, and “space war”, in greater detail.

________________________________________

Here’s Willy Ley’s “Space War” from August of 1939.

Some general “take-aways” from his article are:

1) The technology needed for spacecraft already exists, even in rudimentary form.

2) The possibility exists that civilization will progress to such a point where war will become outlawed. But, given human nature, in the more likely alternative, the potential and impetus for human conflict that’s always existed on earth will continue as man explores space.

3) By definition, the nature of space conflict will parallel aerial combat between warplanes, by occurring in three dimensions.

4) In literary depictions of space warfare, a common plot element has been the use of directed energy weapons, like infrared projectors.

However, a weapon far more mundane and less dramatic, yet more effective, practical, and solidly within the realm of technological development and practical use is some variant of “the gun”: “Well, I still believe that there is no better, more efficient and more deadly weapon for space warfare than an accurate gun with high muzzle velocity. And I believe that an intelligent being from another planet, that is advanced enough to build or at least to understand spaceships, will look like a man – at least to somebody who does not see very well and cannot find his glasses.”

5) The technology envisioned for energy or beam weapons – “ray projectors” – even if these can successfully be developed – is prohibitively heavy and bulky for use in spacecraft.

6) Assuming that some form of “gun” is used in space warfare, the projectiles fired by such weapons would be analogous to those used in conventional, “earth-bound” conflicts, albeit specifically relevant to spacecraft-versus-spacecraft battles. These would be: 1) High explosive thin-walled shells, and 2) Shells containing large numbers of individual non-explosive projectiles.

7) Some science fiction depictions of space warfare rely on the concept of defensive “screens” (analogous to the use of deflector shields in Star Trek?). But, can “screens” of whatever nature – “gravity screens” in particular – even be developed, n light of current and future knowledge about the nature of gravity?

8) Rockets would be a possible weapon in space battles, albeit this being 1939, Ley is discussing unguided rockets. The disadvantages of such weapons are that they could be (relatively) easily spotted, it would be impractical and dangerous to store a large quantity of combustible and explosive material aboard a spacecraft, and, the size and mass of such weapons.

9) Space battles would be characterized by craft camouflaged “night-black”, using any possible measures to reduce their thermal signatures.

10) Ammunition would be used “sparingly” due to the danger of intact ordnance remaining in orbit around the Sun. (Or, any old sun.)

11) It would be essential to compensate for the recoil effects of any weapon – or more likely combination of weapons – located at scattered points on a spacecraft’s hull (think of an analogue to the five gun turrets (four remote-control) of a WW II B-29 Superfortress), on the spacecraft’s trajectory, by the craft’s main engine, or, maneuvering thrusters.

____________________

____________________

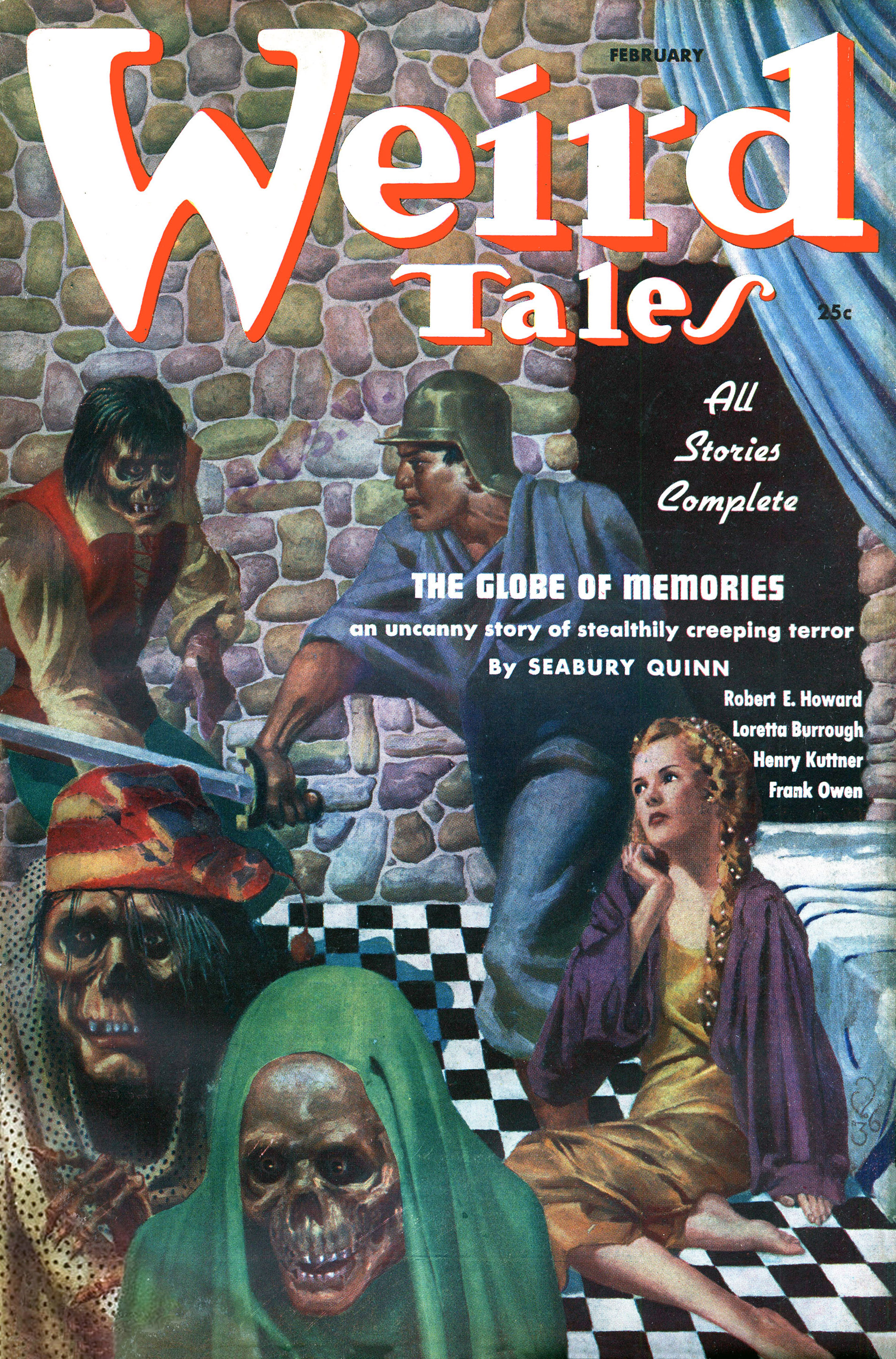

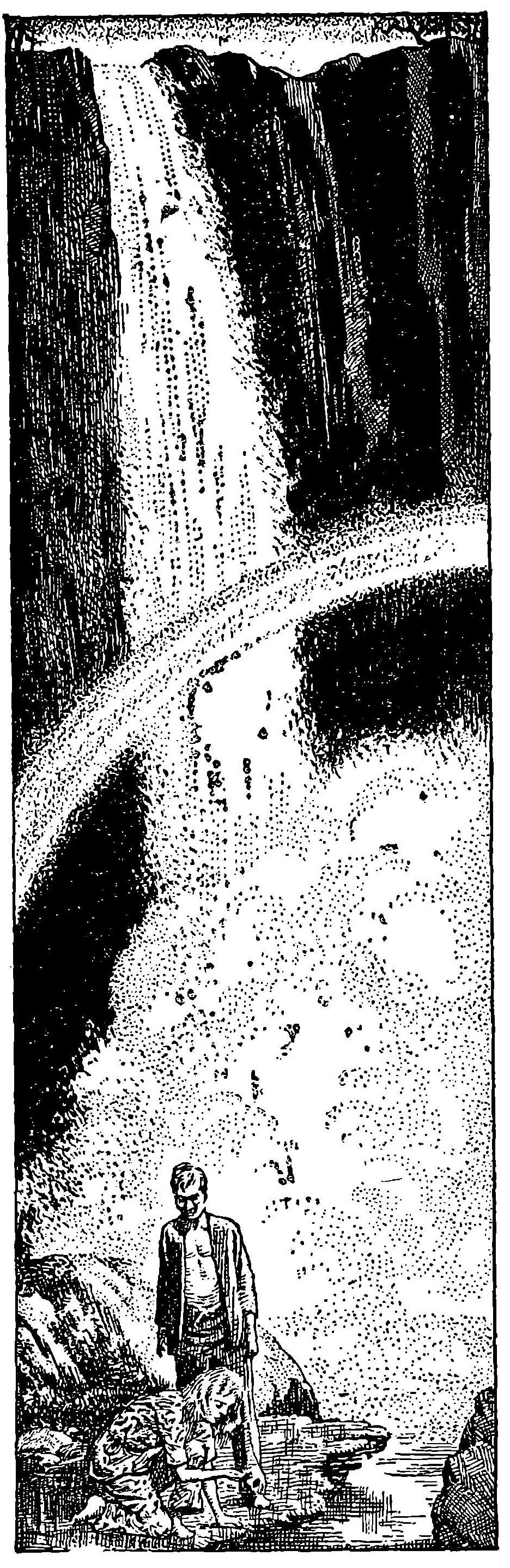

Oh, before we start with Ley’s article, a comment about this issue’s cover art: This is the only issue of Astounding Science Fiction for which the cover illustration – for which any illustration, really – was created by Virgil Finlay. Given Finlay’s superb – sometimes astonishing; almost preternatural; in my opinion quite unparalleled – artistic skill, I’d long wondered why an artist of his caliber had no other association with Astounding, given the magazine’s centrality to the development of science fiction as a literary genre.

The answer to this question – excerpted this from this post – follows:

__________

VIRGIL FINLAY – Dean of Science Fiction Artists

by SAM MOSKOWITZ

Worlds of Tomorrow

November, 1965

Except for an unfortunate experience Finlay might have become a regular illustrator for Astounding Science-Fiction, then the field leader.

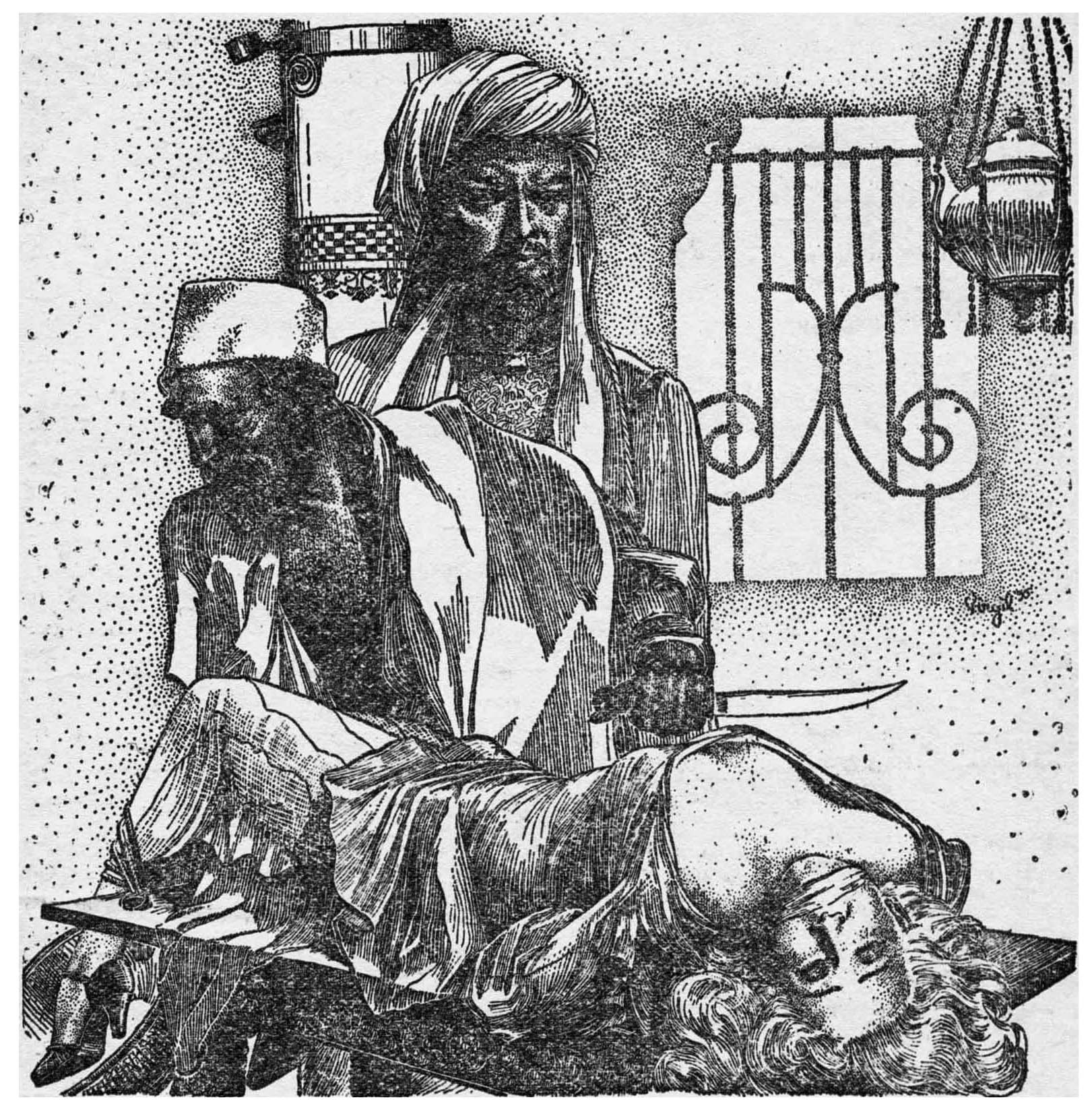

Street & Smith had launched a companion titled Unknown, to deal predominantly in fantasy. Finlay had been commissioned to do several interior drawings for a novelette The Wisdom of the Ass, which finally appeared in the February, 1940 Unknown as the second in a series of tales based on modern Arabian mythology, written by the erudite wrestler and inventor, Silaki Ali Hassan.

John W. Campbell had come into considerable criticism for the unsatisfactory cover work of Graves Gladney on Astounding Science-Fiction during early 1939. So it was with a note of triumph, in projecting the features of the August, 1939 issue, he announced to his detractors:

“The cover, incidentally, should please some few of you. It’s being done by Virgil Finlay, and illustrates the engine room of a spaceship. Gentlemen, we try to please!”

The cover proved a shocking disappointment. Illustrating Lester del Rey’s The Luck of Ignatz, its crudely drawn wooden human figures depicted operating an uninspired machine would have drawn rebukes from the readers of an amateur science-fiction fan magazine. The infinite detail and photographic intensity which trademarked Finlay was entirely missing.

No one was more sickened than Virgil Finlay. He had been asked to paint a gigantic engine room, in which awesome machinery dwarfed the men with implications of illimitable power. He had done just that; but the art director had taken a couple of square inches of his painting, blown it up to a full-size cover and discarded the rest.

The result was horrendous. A repetition of it would have seriously damaged his reputation, so Finlay refused to draw for Street and Smith again.

____________________

____________________

And so, now on to Willy Ley’s article…

SPACE WAR

Suggesting that rays, ray screens, and all super-potent weapons of science-fiction aren’t half as deadly as a weapon we already have.

By Willy Ley

Illustrated by Willy Ley

Astounding Science Fiction

August, 1939

ABOUT ten years ago, Professor Hermann Oberth, the famous rocket expert, made an interesting experiment which, although having to do with rockets, required neither laboratory nor proving ground. It was a legal experiment. Professor Oberth submitted to the German Patent Office a complete description, with drawings, of a “Space Rocket.” It was, virtually, a spaceship with all the details he had been able to think of in many years of study.

After the usual acknowledgment, there was complete silence for some time. Then one day a bulky letter arrived from the patent office, containing the expected rejection. But it was more than just a rejection. Patent offices do not reject things without explaining why. And the staff of the patent office did explain. They had pried the plans apart and patiently and expertly examined every part of them. And after really tremendous research and labor they had arrived at the conclusion that Professor Oberth’s plans could not be patented because every part and device was known to engineering science and had been patented before in some country by somebody else. (1)

The decision, or rather the explanation given, was in a way more valuable than the granting of a patent would have been. It proved that spaceships arc not so far beyond the horizon as most people think – the very conservative and very careful staff of a patent office had found that they existed already – only in parts scattered all over and throughout civilization. Periscopes, air purifiers, air-proof hulls, automatic devices and instruments of all kinds, water regenerators, et cetera, et cetera – they all exist and not even the much-discussed rocket motors are really novel. Devices very similar to those needed on a tremendous scale for spaceships have already been built on a small scale for gas turbines.

It is, of course, true that, in spite of the decision of the patent office, space-ships arc still to be invented. Every one of the thousand and one parts needs special adaptation, re-designing and re-research. There is still a tremendous amount of work to be done, and much has to be “invented.” Point is, however, that there is nothing new in principle that is needed for space travel. It was almost the same story with airplanes forty years ago. Everything needed to build an airplane existed. There was steel tubing and the art of welding it. There were sheet aluminum and rubber. There were wheels and propellers, wings were known and gasoline engines could be bought. The invention of the airplane was delayed because those engines were too weak – it is exactly the same with rocket motors.

With more powerful engines came airplanes. And with airplanes came thoughts of military application. At first only observing was contemplated. Even in actual war – 1914 – airplanes did not combat each other at first. They observed enemy movements were fired at from the ground and retaliated with primitive bombs. But the pilots of two airplanes meeting in the air are said to have saluted each other – flying alone was dangerous enough. Then one day somebody began to shoot with a pistol and soon planes were having machine- gun combats.

It is only logical to assume that space war will follow the advent of the spaceship as aerial warfare followed in the wake of the airplane. Not from the very outset, probably, because the first space-ships will entail sufficient risk of life in themselves. But later spaceships will have means to combat each other in space and one day somebody will find, or create, a reason to use these means. It is possible, though not any too likely, that mankind will have progressed beyond the use of brute force when space travel has advanced to a fair degree of perfection. And if by then war has already been successfully outlawed, there will be space police and blockade runners. There will be combat, even if not war.

So much for the likeliness of battles in space – even without the famous invasion from an alien solar system. How will these battles be fought? New means of transportation bring new kinds of battle tactics. Roman chariots fought in another manner than the horsemen of Dshingis Khan. Byzantine galleys employed other tactics than Sir Francis Drake, and he had other ideas of naval battle than the commander of the U.S.S. Washington.

IN AERIAL BATTLE a new element became important, the maneuverability in three dimensions. It was not the better gun or the faster plane that decided many single engagements, but the Immelmann turn. Evidently space war will develop its own tactics – but tactics depend also to a very great extent on the type of armament in use. That, of course, does not present any question to the science-fiction fan. He knows it by heart from hundreds of stories, the authors of which neither overexerted their imagination nor perceive a need for too much originality. Traditionally spaceships attack each other with heat-ray projectors of incredible temperature and tremendous capacity; they probe into each other’s vitals with searing needle rays. They bombard each other’s screens with proton guns and barytron blasters. They waste energy in appalling quantities, they do anything but shoot.

____________________

Figure 1. Pressure curves the barrels of guns.

____________________

To pull the lanyard of a shiny 75-millimeter nickel-steel gun would be too trivial a thing to do. Just about as trivial, in fact, as to picture a race of bearded men in white silk dresses armed with crossbows on a planet of Beta Draconis. The beings that live there must be walking octopi, waving heat guns and disintegrator pistols in their tentacles. Normal human-looking people would not be hostile enough to the visitors from Terra, and spaceships with simple guns would certainly be ridiculous and puny. Besides, guns would be to no avail against the ultrarefractory super alloys of the spaceships, and the shells would simply be deflected by force fields.

Well, I still believe that there is no better, more efficient and more deadly weapon for space warfare than an accurate gun with high muzzle velocity. And I believe that an intelligent being from another planet, that is advanced enough to build or at least to understand spaceships, will look like a man – at least to somebody who does not see very well and cannot find his glasses.

Before going into detail about the advantages of guns it is advisable to contemplate the relative merits of ray projectors. That they do not exist now is immaterial; science-fiction is not only concerned with things that are but also with those that might be. How would they look if they did exist? They would consist of two main parts, the mechanism that produces and projects the rays and the power plant that feeds said mechanism.

Power plants are notoriously heavy and, even if we assume atomic power, the power generator will not be just a vest-pocket affair. It would probably need a lot of insulation and a powerful cooling device. We can say with certainty that it would be heavy and bulky. Also, it will probably be sensitive against shaking and jarring, and it would be unpleasant indeed to see all the atomic converters go out of action in the middle of a battle. The ray generator itself would most certainly be sensitive since we have to assume tubes of some kind. And these sensitive ray projectors would have to be in the outer hull of the ship – or even outside the outer hull – so that they do not damage the wrong hull.

So much for the “merits” of ray generators. Now the rays themselves. Even the most powerful and most fantastically destructive ray will need some time to inflict damage. Which implies the need for complicated sighting and focusing devices. How well the rays will focus is another question. Almost invariably the beams will spread out with distance. The farther the target is away the weaker the radiation becomes. The weaker it becomes the longer it has to strike. But holding a ray on a fast-moving distant target, that might be practically invisible with black paint against the background of black space, is no small job.

Besides, those rays are supposed to be more than mere searchlights. They are supposed to have unpleasant destructive qualities, being twelve thousand degrees hot, for example. Naturally the generator has to be able to endure its own heat. But, if there is an insulating material that holds out against the energies released at the giving end, it is hard to understand why the same insulator should not be usable to safeguard the hull of the ship that is being rayed – especially since the energy concentration at the receiving end is only a fraction of that at the giving end.

John W. Campbell evaded all these troublesome questions nicely in his “Mightiest Machine” by introducing the transpon beams. These rays are fairly innocent in themselves, but they have the ability of carrying a large variety and an enormous quantity of vicious radiations originating elsewhere and not touching the projectors. It is possible that something like this might be accomplished one day, but ordinary rays, as they are usually featured in science-fiction stories, have no place in actual future space war. Even if they could be generated they would not have any practical military value.

A GUN is a much nicer instrument. It is compact and sturdy, cannot be damaged by anything less potent than a direct hit from another gun, and does not require a special power plant. Compared to what one would have to carry around to produce even feeble rays the weight of a gun is small. Besides, a gun is something we do know how to handle. More than six centuries of continuous use have taught us how to take advantage of the fact that certain mixtures of chemicals burn with utmost rapidity and produce large quantities of gases while doing so.

That fact permits three main types of possible application, every one of them in use in ordinary warfare and fit to be used in space war, too. The large volume of gas that is generated suddenly can either he used to destroy its container and whatever happens to be around – that’s the principle of the bomb. Or it might be discharged comparatively slowly through a hole in the container so that the recoil moves the container – the principle of the rocket. Finally it might be discharged suddenly through a tube which is blocked by a solid movable object that is then blown out vehemently at high speed just like a dart from a blow gun – the principle of the firearm. All three, bomb, rocket and gun, were invented in rapid succession soon after the discovery of gunpowder.

____________________

Figure 2. Three types of explosive shells. Type A is a light, bursting shell, for surface damage. B, heavily cased with armor, is designed to penetrate steel and concrete armor before bursting. C is a sort of “flying machine-gun,” a shrapnel shell to scatter hundreds of deadly pellets as bursting.

____________________

Figure 3. Antirecoil device for gases. The explosion gasses, turned backward, tend to kick the rifle forward as hard as the bullet’s recoil kicks it backward.

____________________

The latter was found in China around the year 1200 A.D., certainly not much earlier – the statements of old encyclopedias notwithstanding. Bombs and powder rochets were used for the first time in 1232 during the bottle of Pien-king. They were then “newly invented.” As to guns we think that we even know the exact year of their invention. The Memoriebook (chronicle) of the city of Ghent contains under the year 1313 the entry:

“Item, in dit jaer was aldereerst gevonden in Duitschland het gebruik der bussen van eenen mueninck.” Translation: “By the way, during this year the use of bussen was discovered for the first time by a monk in Germany.”

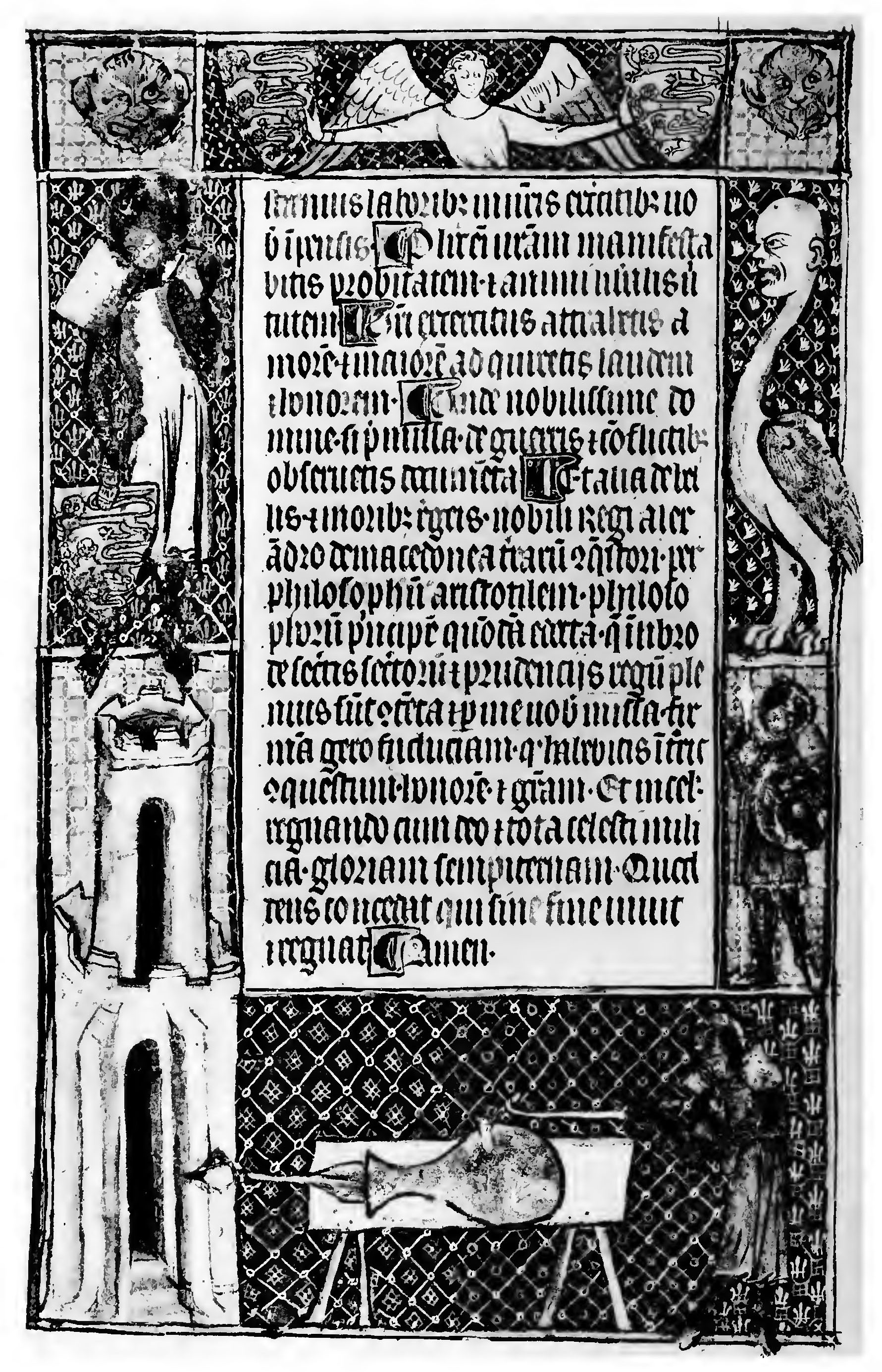

“Bussen” meaning portable guns. The oldest picture of a gun can be found in an Oxford manuscript, De Officiis Regum, from the year 1326. Eighty years later guns were known in all civilized countries.

[Note: I believe that Willy Ley made an error in the manuscript’s title – De Officiis Regum – which should actually be De nobilitatibus, sapientiis, et prudentiis regum, which translates as “Of the Nobilities of Wise and Prudent Kings“. Indeed penned Walter de Milemete in 1326, the book was, “…commissioned by Queen Isabella of France [as a] treatise on kingship for her son, the young prince Edward, later king Edward III of England.” The book’s now available at Archive.org, where it’s described as having been “Reproduced in facsimile from the unique manuscript preserved at Christ Church, Oxford [1913], together with a selection of pages from the companion manuscript of the treatise De secretis secretorum Aristotelis, preserved in the library of the Earl of Leicester at Holkham hall.”

The illustration referred to by Willy Ley can be found on page 140 (248 of the digitized book), where it appears at the bottom of the page…

Though the digital version of the the Oxford edition appears in black & white, the specific illustration in question – the oldest known visual representation of a gun (actually, a cannon) – is found in the Wikipedia entry for Walter de Milemete. Here is is…]

But it took more than four centuries until the science of ballistics came into being. A great many other sciences, especially mathematics, had to be developed first before the performance of a gun could be predicted to a certain extent.

Ballistics arc extremely complicated, and it is hard to tell whether interior or exterior ballistics present fewer or lesser headaches. The term “exterior ballistics” applies to the movement of the projectile from the moment it leaves the muzzle of the gun until it hits the target. “Interior ballistics,” consequently means the movement of the projectile within the gun barrel. The principles are simple in both cases.

The distance reached by a projectile is determined by its muzzle velocity that should be as high as possible and by the angle of elevation where 45 degrees represents the optimum. High muzzle velocity is, therefore, the main goal, and the laws of interior ballistics tell how it can best be attained. There are only a few forces at work. The expanding gases that result from the explosion of the driving charge push the projectile ahead of them, the higher the pressure, the faster. And the longer the barrel the more time to push. Counteracting forces are the inertia of the projectile and its friction against the walls of the barrel. It seems, therefore, that the barrel should he very long and very smooth, the pressure very high and the projectile very light.

Unfortunately it is not quite as simple as becomes apparent if we follow the events in a more detailed form. The shot begins with the ignition of the driving charge. It is here where things look most beautiful. One kilogram of ordinary black gunpowder produces 285 liters of gas at the temperature of zero degrees centigrade, the freezing point of water. One kilogram of TNT develops 592 liters, one kilogram of nitroglycerin 713 liters, and one kilogram of nitro-cellulose powder even 990 liters. Now these volumes are valid for zero degrees centigrade. But the gases are hot, their volume increases by about one third of the zero degree volume for each 100° C. rise. And the temperature of combustion is high, about 2000° C. for black powder, 2600° C. for TNT, 3100° C. for nitroglycerin and 2200° C. for nitro-cellulose powder. There is a limit as to what the barrel can stand and don’t forget that it is supposed to have a service life, too. Things are a little easier if the powder burns rapidly but not instantaneously; the reason, incidentally, why only a very few known explosives can be used as driving charges. A short moment after complete combustion of the driving charge the internal pressure reaches its highest point, afterward expansion alone works.

THE LENGTH of a barrel is usually expressed not in inches or centimeters, but in calibers, a word which came from the Arab, where it means “model” (standard). Very short stubby mortar barrels are 12-15 calibers long, heavy naval gun 40-50 calibers and infantry rifles even 90 calibers. They are not smooth but “rifled”, having a spiral groove which forces the projectiles to spin around their longitudinal axes. Artillery shells fit the barrel loosely – the rifle effect and the gas tight fit are accomplished by copper rings laid around the shell.

We have arrived at the point where the gases drive the shell by their expansion only. The speed of the projectile is still increasing then, but not for very long. The infantry rifle 98 [referring to the German Gewehr 98 bolt action rifle?] that was and is in use in a number of European armies and has been investigated very thoroughly, may now serve as an example, its bore is 0.3 inches, the “bullet” weighs 10 grams, the driving charge 3.2 grams. The barrel is 29.1 inches, or about 90 calibers long.

The bullet leaves the muzzle with a velocity of 2936 feet per second, involving a small loss of energy since the muzzle velocity could be 66 feet higher if the barrel were 45-4 inches or 150 calibers long. These figures show how much the friction in the barrel retards the bullet. To attain a speed of 2936 feet per second a barrel length of 90 calibers is required. But an additional length of 60 calibers would increase the muzzle velocity by only 66 feet. No wonder the designers preferred to save these 66 feet, and save weight and material. If the barrel was much longer, the bullet would not leave it. That’s what would happen in the case of rifle 98 if the length of the barrel surpassed 23 feet.

In special cases longer barrels were built: The 80-mile gun that fired at Paris from the forest of Crepy in March, 1918 (2) had a barrel that was 118 feet or 170 calibers long. However, only three quarters of that barrel were rifled, the last 45 calibers of length were smooth. Another retarding factor, not often mentioned and apparently not yet fully determined is the air above the shell in the barrel. Since the projectile acquires supersonic speeds, that air cannot escape but has to be compressed, which might mean a considerable loss in the case of a long gun of large caliber.

Point one in favor of guns in space war: they do not have to spend that energy.

When the projectile leaves the muzzle the trouble really starts. Older books say that the trajectory is a parabola – it is elliptical with the center of the Earth as one of the focal points of the ellipse. The trajectory is influenced by the rotation of the Earth, by the attraction of large mountains, by barometric pressure and by the humidity of the air and by a number of other factors that might be avoided by careful design. Incidentally, streamlining would be useless; we deal with supersonic velocities. While the shell rises the velocity decreases until the peak of the flight is reached. Then the velocity increases again, due to gravitational attraction, and decreases with mounting speed due to increasing air resistance.*

____________________

*Most of these factors become noticeable only in long trajectories. The changes in velocity are beautifully shown in the following table, calculated by Max Valler for the trajectory of the Paris Gun – authentic data are still secret.

| angle | distance (km) | altitude (km) | velocity (km/sec) | time (sec) |

| 54 | 0 | 0 | 1.5 | 0 |

| 53 | 3.45 | 4.67 | 1.3 | 4.2 |

| 50 | 10.83 | 14.00 | 1.06 | 14.3 |

| 45 | 19.70 | 23.72 | .93 | 27.3 |

| 40 | 26.80 | 30.33 | .86 | 38.2 |

| 25 | 43.07 | 41.04 | .72 | 62.1 |

| 0 | 63.34 | 46.20 | .65 | 94.5 |

| 25 | 83.55 | 41.60 | .71 | 120.0 |

| 40 | 99.06 | 31.20 | .84 | 150.5 |

| 50 | 115.99 | 16.60 | .95 | 173.3 |

| 53 | 122.00 | 6.12 | .94 | 191.0 |

| 58 | 126.00 | 0 | 0.86 | 199.0 |

____________________

The main factors are therefore, gravity and resistance – two more points in favor of the use of guns in space. There is no air resistance and the gravitational fields are weak where spaceships usually travel.

That bullet from infantry rifle 98 has near its muzzle 3000 foot pounds of kinetic energy. When it hits a target 3280 feet (1 kilometer) from the muzzle its kinetic energy is only 336 foot pounds, and at 2 kilometers a mere 88 foot pounds. The extreme range of that rifle is about 4 kilometers (2.5 miles), but if there were no air it would carry more than 70 kilometers (43.5 miles). Rifles do not attain more than 5% of their vacuum range under normal surface conditions, field artillery pieces attain about 20%, heavy artillery shells about 25%, long naval rifles of large caliber 30%, and long-range guns up to 50%, because the longer part of their trajectory is situated in the near- vacuum of the stratosphere.

In space in a weak gravitational field, the infantry rifle bullet would arrive at a target 20 miles distant – you could hardly aim without a telescope at something farther away – with about 3020 foot pounds of kinetic energy. No, “3020” is not a printing error, because the muzzle velocity would be higher, due to the lack of air resistance in the barrel!

AFTER being pleased so much with the performance of a portable rifle we’ll have a look at “real” guns. There exists an especially nice field piece, La Soixante-quinze, the famous French 75 millimeter gun. It has a 20-caliber barrel, about 7 feet 4 inches long. Its shell weighs 14.3 pounds, the muzzle velocity in air is 1970 feet per second, the kinetic energy at the muzzle about 2,800,000 foot pounds. [!?]

From Copper Range Productions, here’s an interesting video about the history, design, and use of the French 75 gun.

The barrel of the .75 weighs about 680 pounds, each cartridge about 22 pounds, so that gun, additional equipment and 150 rounds of ammunition amount to about two tons – not excessive a weight for a ship that does not have to carry passengers or cargo – say a Patrol cruiser – but very impressive an armament for a spaceship. Of course, the gun would not be a three-inch field piece. In a French paper on Avions de gros bombardement it was very recently pointed out that guns are much heavier than necessary.

____________________

Figure 4. English war-rocket. This rocket shell is listed in the official British tables of war equipment – a modern, practical rocket shell.

____________________

Designers simply did not pay much attention to weight as long as the gun did not become too heavy for land transport, or if – in case it was too heavy – could be divided into easy loads. Besides, military experts have their ideas about service life. One of my closest friends once designed a new type of compass for a firm working for one of the large European navies. After exhaustive tests that compass was rejected because it was too light! It was later redesigned with parts and casings that were not stronger than the original parts, but multiplied the weight. The weight of gun barrels, to get back to the topic, could be reduced to about half without visibly shortening of service life and it could be reduced to a quarter if a shorter service life would be accepted. That brings even a six-inch long-range gun within reach for large cruisers that do patrol duty; for example, in circling planets. “Six-inch long range,” incidentally, means just that in space, it could shoot at enemies farther away than a portable telescope could show.

So there is certain no need for a special weapon. How about special shells? On Earth three main types are in use: One that dumps as much high explosive as a thin-walled shell will hold on the enemy; one that has to pierce armor and has, therefore, thicker walls and a very strong tip, and one that contains little explosive and many lead balls to scatter around against living targets.

Your first guess is probably that the armor-piercing type is the given projectile for space war. Which raises the question how much armor is to be pierced. Terrestrial field guns are equipped with a shield supposed to protect the gun crew against rifle and machine-gun fire and smaller splinters. Before the World War a shell of 3 millimeters was considered sufficient, but direct rifle fire from distances of a thousand feet or less penetrated them.

____________________

Figure 5. Cross-section of proposed space rocket shell. To get striking power in a rocket equivalent to a 75 shell, the driving charge of the rocket would be inordinately heavy.

____________________

Light battle cruisers on the seas carry a six-inch armor around; it would afford protection against hits from fairly distant 75 mm. guns. However, a six-inch armor is considered light; most warships carry ten-inch armor plate, and the heaviest battle wagons show up to 30 inches of armor. Now a battleship has only an armor belt, protecting the sides where hits are most likely, and protecting those spots where hits would be most destructive. A large section of the ship is protected by the water in which it floats. Spaceships are not so lucky as to have vulnerable points: they are vulnerable all around. Therefore, they need armor plate all over the hull.

The weight of such an armor is a nice example for mathematical enjoyment at breakfast or during a subway ride. We’ll say that a fair-sized spaceship is 90 yards [82.3 meters; 270 feet] long and 20 yards [18.3 meters; 60 feet] in diameter. To make matters easier we shall assume that the shape is cylindrical, to make up for the difference in surface between cylinder and cigar shape we’ll forget about top and bottom of the cylinder and restrict ourselves to the curved surface. That surface is equal to the length of the cylinder, multiplied by the diameter, times pi which makes 5070 square yards. One square yard of six-inch armor plate weighs not quite a ton. Multiplied by the number oi square yards we arrive at, roughly, twelve million pounds!

You can cut down for the thickness of the armor as much as you want. It will always be too heavy, until you arrive at plates of a thickness the outer hull would haw to have anyhow.

In short, a Spaceship cannot be protected by plate armor. Its only defense is its offensive power, since it can always carry guns hundreds of times as powerful as the heaviest possible armor. So we don’t need armor piercing projectiles, any projectile will penetrate the hull – even rifle bullets.

The important difference is that a spaceship cannot be sunk either – a fact not stressed enough by science-fiction authors. When a battleship gets a few really serious holes, it is soon out of action and it is relatively unimportant whether the crew abandons ship or sinks with it firing as long as they are above water. A few bad hits that struck a spaceship may disable it as a means of transportation, but it still does not disappear. If every man wears a spacesuit the loss of air can be temporarily disregarded. The various gun posts can and will continue firing until every man on board is disabled. (3)

Space war, therefore, calls for shells that either blast the enemy to smell pieces at once or for shells that quickly disable every man on board. Which means that either high-explosive shells with thin walls and much H-E are used, or else those shells that contain large numbers of individual bullets should be steel balls and not lead balls, as in terrestrial warfare If the range is short – as “short” ranges in space go – machine guns are not bad at all, or else that nice contraption that goes under the name of “Chicago Piano,” consisting of eight one-pounder rapid-fire guns mounted on one beam, each firing 200 rounds per minute. [QF 2-pounder Mk VIII naval gun, a.k.a. “multiple pom-pom”.] If a spaceship were subjected to the concert of a Chicago Piano for only one minute it would certainly look even worse than after a treatment with heat and disintegrator rays, especially since those rays are usually blocked in stories by adequate screens.

____________________

“An eight gun 2-pounder QF Mk VIII anti-aircraft ‘Pom Pom’ gun installation.” (From History of War.)

____________________

“If a spaceship were subjected to the concert of a Chicago Piano for only one minute it would certainly look even worse than after a treatment with heat and disintegrator rays…”

“The pods, assholes!”

(From The Expanse – “Doors and Corners“)

____________________

THOSE screens deserve a short discussion, too. As far as ray screens against hostile rays are concerned, we do not need to worry for long. Without effective rays there is no need for ray screens. But it is another story with those fictive screens that are supposed to offer protection against flying pieces of matter charged with kinetic energy. Could those force fields, or meteorite detectors, or whatever you like to call them be made to actually protect a spaceship? Strong electric or magnetic fields can deflect material bodies, but the influence is much too weak to avail against bullets with supersonic speeds. To create a field of such power and range would require equipment of such a ponderous mass and weight – even assuming atomic power – that nickel-steel armor might be lighter. Only gravity screens would really afford protection.

A gravity screen is supposed to set up a difference in gravity potential and to create what might be called a gravity shadow. A projectile that were to enter a gravity shadow would need as much kinetic energy as is normally required to overcome the difference of gravity potential in question. Since it is also usually assumed that the power of gravity screens can be made to vary, the commander of the ship could “adjust” his screens according to enemy fire.

The trouble with gravity screens is not that we do not know how to make them, but that they cannot be made at all. Devices that “shield off” gravity belong to the category of “permanent impossibilities,” things that cannot be done just as you cannot construct a seven-cornered polygon or trisect a given angle. The problem of the gravity screen has to be regarded as having been solved just as the problem of the perpetuum mobile has been solved: negatively, it cannot be done.

All this applies, however, only to “gravity screens” of the cavorite type and similar marvelous compounds. It does not hold true for what may be termed a “counter field.” Unfortunately we do not know what gravity really is – but it is certainly a force of some kind. If, one day, somebody discovers the truth about gravity he might also find a way to create gravity fields artificially. Now we can conceive of a magnetic field that could eliminate the influence of Earth’s field if the latter were magnetic instead of gravitational. (I am not speaking about Earth’s real magnetic field.)

Similarly we can conceive of a counter field eliminating the effects of the natural gravity fields. To build up a field of the required strength needs lots of power, to be sure, but one might assume that the initial supply could be furnished by a stationary power plant. Such a counter field would, of course, have most of the features of cavorite – among them the protection against projectiles of less kinetic energy than the difference of gravity potentials in question.

With this vague hope for possible protection of spaceships we may safely return to the original topic: means of destruction. Guns and machine guns were found to do nicely – and rocket shells?

Rockets began as weapons of war, they were revived for this purpose by Sir William Congreve in 1804 when there was no other competition for them than smooth-barreled guns of tremendous weight that carried a mile without any accuracy worth mentioning. In fact, Congreve’s rockets and Hale’s later stickless rockets were more accurate than the contemporary guns; hard to believe, but stated in many of the old reports on rocket tests.

And, contrary to popular belief, war rockets were retained in the Service by Great Britain even in the beginning of the twentieth century. The “Treatise on Ammunition,” issued in 1905 [see 1915 edition at Archive.org] by the (British) War Office, still stated: “Rockets are employed in the service for signaling, for display, as weapons of war, and in conjunction with the life-saving apparatus.” The war rocket officially termed, “Rocket, War, 24-pr., Mark VII, (C). painted red,” was described as being made of steel tubing and cast iron. The average range given was 1800 yards, they had no guiding stick but a device to make them rotate in flight. If these rockets were still used in 1905 or later, they were probably used in colonial service. Despite very many attempts made just at that time to revive war rockets, no army introduced them. Rocket shells behaved, in all the tests that were made, even more erratically in the air than ordinary shells.

It would be different in space. No air resistance would disturb the flight of a rocket-driven shell. And instead of a heavy steel barrel only a thin-walled launched tube would be needed that could even be made of aluminum or magnesium alloys.

The first military objection against rocket shells would be that they could be more easily seen. This, however, could be overcome in using a very high acceleration with short burning period. The driving charge, incidentally, should be powder, not liquids. Powder it not as powerful and not as adaptable as liquid fuel, to be sure, but easier to handle and less expensive because it eliminates the need for mechanisms like combustion chambers, injection nozzles, pressure devices and a host of valves. Powder has the further advantage of having a natural tendency for shorter combustion periods and higher accelerations.

But guns are still superior, this time because of lesser weight!

If the shell part of the rocket shell shall be the same as that of a 75 mm. gun. and if the final velocity of the rocket shell, after complete combustion of the driving charge, shall be equal to that of a gun projectile the comparison of weights looks as follows:

GUN

weight of the gun – 880 pounds

weight of 100 cartridges – 2200 pounds

total weight – 3080 pounds\

ROCKETS

launching tube, etc. – 45 pounds

100 shell heads – 1430 pounds

100 rockets with sufficient driving charge – 4300 pounds

total weight – 5775 pounds

Thin, of course, does not mean that rocket shells will not be built. For patrol cruisers guns are better, but other ships will not carry 100 rounds of ammunition all the time, as soon as less than twenty rounds are carried, the rockets are lighter. (There are a few story plots hidden in this statement.) One might conceive of heavy space torpedoes built along the lines of rocket shells, 10 feet long and weighing 1 1/2 tons. But I simply won’t like so much powder in one piece on board – and the construction of such a torpedo with present-day methods of manufacture is, by the way, impossible.

SPACE WAR certainly has its peculiar features, quite different from those pictured in stories, but peculiar just the same. The story picture of shining ships that battle with searing rays and flaming screens is so highly improbable that it can simply be termed wrong. There won’t be any rays and there won’t be screens, especially not the latter because you would be unable to shoot while you had them working.

Instead there would be ships painted night-black, the camouflage of space, carrying guns of incredible range and immensely destructive power. The ships would be extremely vulnerable, but at the same time they could not sink and would be capable of inflicting fatal damage as long as a soul on board is alive.

They would not steam into battle with flying colors, but try to approach unseen with all lights extinguished, avoiding the light background of the Milky Way. If the battle is finally opened ammunition would be used very sparingly, not only because the supply is limited, but because missing is almost as bad as being hit. The 2000-3000 feet per second of muzzle velocity do not count very much as compared with the orbital speed of the planets and all the shells that missed show up again at the point of battle after one or two or three years when they have completed their full orbit around the Sun.

That their own fire throws them off course is another reason for few shots. Each 75 mm. shell, weighing 14.3 pounds and leaving in space the muzzle with a velocity of say 2300 feet per second, produces a recoil of 1000 pounds. And the powder charge, weighing, say, 6.5 pounds, and leaving the muzzle with approximately 6600 feet per second produces another 1300 pounds of recoil. A single shot would naturally not influence the course of a 3000-ton patrol cruiser very much, but during a prolonged battle there will be deflections to be corrected by the rocket motors.

On second thought I take that back. The guns do not have to have a recoil that influences the ship. Several years ago Schneider in Creuzot (France) announced a recoil eliminator, based on the difference in speed between shell and driving gases. Since the gases are between two and three times as fast as the shell, they overtake it as soon as it clears the muzzle. The Schneider-Creuzot device was intended to catch these gases and to deflect them by 180 degrees so that their recoil counteracts that of the shell. The example of the 75 mm. gun has shown that the gases, weighing only 6.5 pounds, produce theoretically 1300 pounds recoil, because they are about three times as fast as the 14.3-pound shell that produces only 1000 pounds of recoil. If all the gases could be caught and deflected a full 180 degrees, the gun barrel would actually jerk forward with each shot. Naturally some of the gas simply follows the shell – but tests have shown that the remaining recoil is very low.

There is one remark I wanted to make all through this article, but up to now 1 did not have an opportunity to do so. What I wanted to say was that there was no talk of armament in Professor Oberth’s patent application.

(1) This decision was entirely in accordance with German patent laws. In other countries a patent might have been granted under the same circumstances.

(2) Usually miscalled “Rig Bertha”: the official name was “Kaiser Wilhelm Gun,” the common name “Paris Gun.” “Big Bertha” was the tame of the mobile 17-inch mortar of Krupps. Both guns were designed by Professor Rausenberger [Fritz Rausenberger].

(3) I recall only one story where this point was stressed. Campbell’s “Mightiest Machine.” The fact is also hinted at in Dr. E.E. Smith’s “Skylark III” during the first encounter with the Fenachrome, but it is not especially emphasized.

— References, Related Readings, and What-Not —

Willy O.O. Ley, at Wikipedia

Virgil W. Finlay, at Wikipedia

Space War, at Atomic Rockets

Warfare in Science Fiction, at Technovology

Weapons in Science Fiction, at Technovology

— Here’s a book —

Wysocki, Edward M., Jr., An ASTOUNDING War: Science Fiction and World War II, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, April 16, 2015

— Lots of Cool Videos —

Why Every Movie Space Battle Is Wrong (at Nerdist) 5/11/17)

The Truth About Space War (4/12/18)

Electromagnetic Railguns – The U.S Military’s Future Superguns – 200 mile range Mach 7 projectiles (11/4/17)

Will Directed Energy Weapons be the Future? (6/12/20)

Best Space Navies in Science Fiction (2/10/20)

5 Most Brilliant Battlefield Strategies in Science Fiction (5/8/20)

5 Things Movies Get Wrong About Space Combat (5/12/20)

6 More Things Movies Get Wrong About Space Battles (5/28/20)

Why “The Expanse” Has the Most Realistic Space Combat (6/21/20)

Be Smart – Joe Hanson

The Physics of Space Battles (9/22/14)

The Real Star Wars (7/19/17)

5 Ways to Stop a Killer Asteroid (11/18/15)

Science & Futurism with Isaac Arthur (SFIA) – Isaac Arthur

Space Warfare (11/24/16)

Force Fields (7/27/17)

Interplanetary Warfare (8/31/17)

Interstellar Warfare (3/8/18)

Planetary Assaults & Invasions (5/17/18)

Attack of the Drones (9/13/18)

Battle for The Moon (11/15/18)

What If There Was War in Space? (12/23/18)

Art: “The Luck of Ignatz” – Virgil Finlay’s Preliminary cover for Astounding Science Fiction, August, 1939