Category: Judaism

Franz Kafka – Letters to Milena (Translated and with an Introduction by Philip Boehm) – 1990 [Anthony Russo]

It’s only in my dreams that I am so sinister.

Recently I had another dream about you,

it was a big dream, but I hardly remember a thing.

I was in Vienna, I don’t recall anything about that,

next I went to Prague and had forgotten your address,

not only the street but also the city, everything,

one the name Schreiber kept somehow appearing,

but I didn’t know what to make of that.

So I had lost you completely.

In my despair I made various very clever attempts,

which were nevertheless not carried out –

I don’t know why –

I just remember one of them.

I wrote on an envelope: M. Jesenski and underneath

“Request delivery of this letter,

because otherwise the Ministry of Finance will suffer terrible loss.”

With this threat I hoped to engage the entire government in my search for you.

Clever?

Don’t let this way you against me.

It’s only in my dreams that I am so sinister.

(September, 1920)

But here the transmutability came into play…

Yesterday I dreamt about you.

I hardly remember the details,

just that we kept on merging into one another,

I was you,

you were me.

Finally you somehow caught fire;

I remembered that fire can be smothered with cloth,

took an old coat and beat you with it.

But then the metamorphoses resumed and went so far

that you were no longer even there;

instead I was the one on fire and I was also the one who was beating the fire with the coat.

The beating didn’t help, however,

and only confirmed my old fear that things like that can’t hurt a fire.

Meanwhile the firemen had arrived and you were somehow saved after all.

But you were different than before,

ghostlike,

drawn against the dark with chalk,

and you fell lifeless into my arms,

or perhaps you merely fainted with joy at being saved.

But here the transmutability came into play:

maybe I was the one falling into someone’s arms.

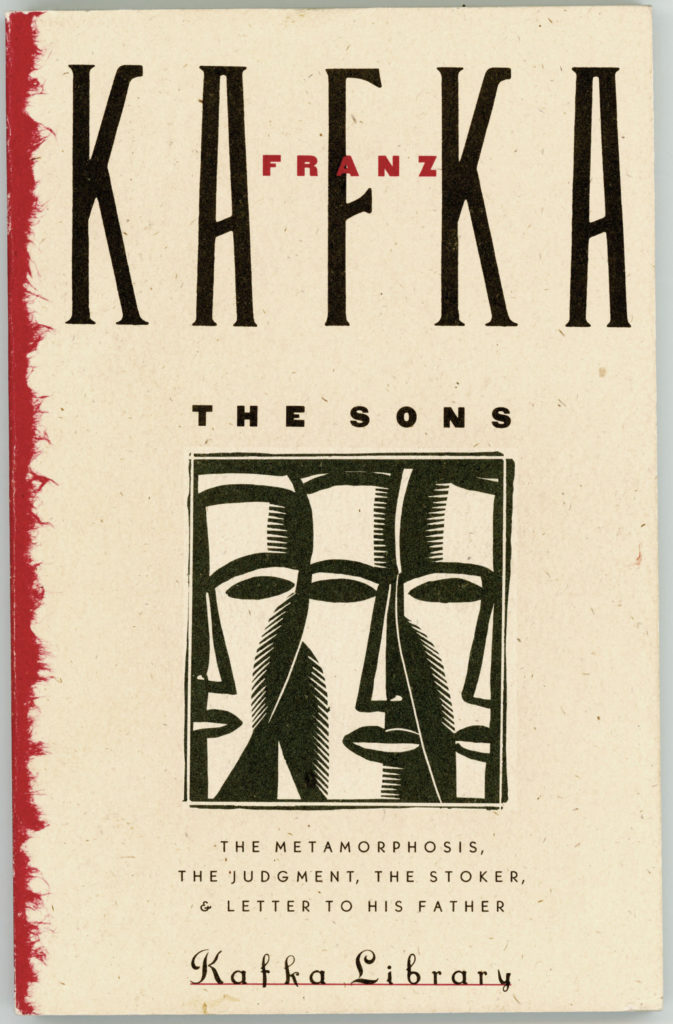

Franz Kafka – The Sons (Introduction by Mark Anderson) – 1989 [Anthony Russo]

…because you once mentioned in passing that I too might be called to the Torah.

…because you once mentioned in passing that I too might be called to the Torah.

That was something I dreaded for years.

But otherwise I was not fundamentally disturbed in my boredom,

unless it was by the bar mitzvah,

but that demanded no more than some ridiculous memorizing,

in other words,

it led to nothing but some ridiculous passing of an examination… (p. 147)

Marrying,

founding a family,

accepting all the children that come,

supporting them in this insecure world

and perhaps even guiding them a little,

is, I am convinced, the utmost a human being can succeed in doing at all.

That so many seem to succeed in this is no evidence to the contrary;

first of all, there are not many who do succeed,

and second, these not-many usually don’t “do” it,

it merely “happens” to them;

although this is not that utmost,

it is still very great and very honorable

(particularly since “doing” and “happening” cannot be kept clearly distinct).

And finally, it is not a matter of this utmost at all,

anyway, but only of some distant but decent approximation;

it is, after all, not necessary to fly right into the middle of the sun,

but it is necessary to crawl to a clean little spot on Earth

where the sun sometimes shines and one can warm oneself a little. (p. 156)

Franz Kafka – Diaries (Edited by Max Brod) – 1948 (1988) [Anthony Russo]

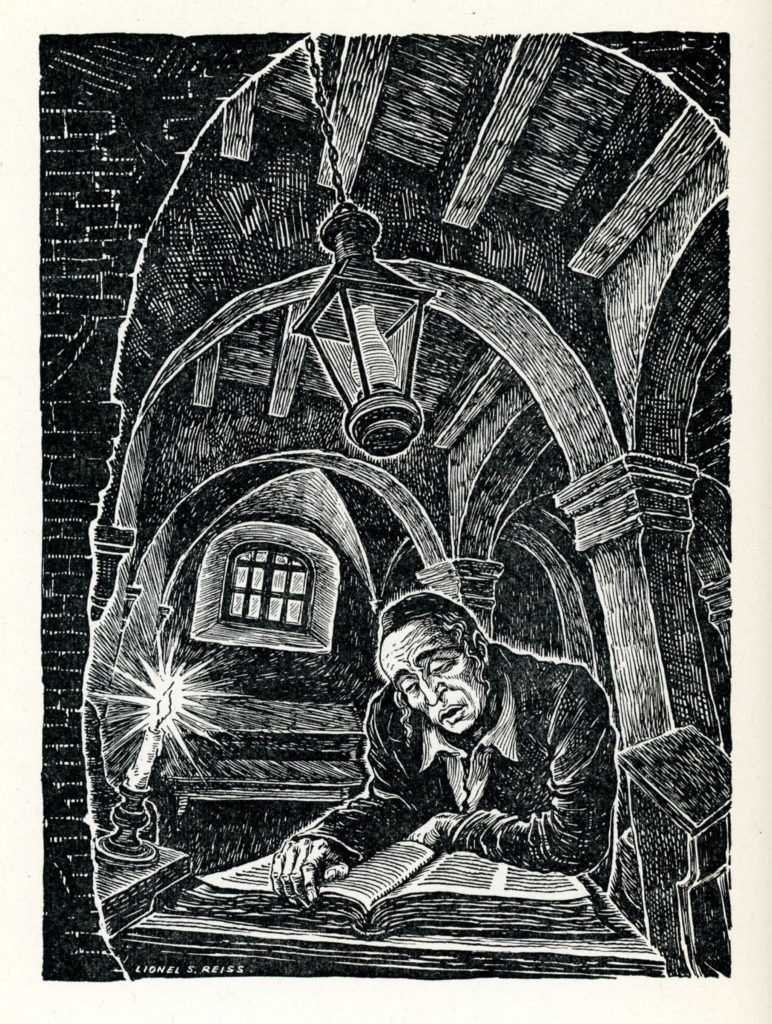

What have I in common with Jews?

I have hardly anything in common with myself

and should stand very quietly in a corner,

content that I can breathe. – January 8-11, 1914

June, 1914 (pp. 279-280)

There are certain relationships which I can feel distinctly

but which I am unable to perceive.

It would be sufficient to plunge down a little deeper;

but just at this point the upward pressure is so strong

that I should think myself at the very bottom

if I did not feel the currents moving below me.

In any event, I look upward to the surface

whence the thousand-times-reflected brilliance of the light falls upon me.

I float up and splash around on the surface,

in spite of the fact that I loathe everything up there and –

August 6, 1914 (p. 302)

What will be my fate as a writer is very simple.

My talent for portraying my dreamlike inner life

has thrust all other matters into the background;

my life has dwindled dreadfully,

nor will it cease to dwindle.

Nothing else will ever satisfy me.

But the strength I can muster for that portrayal is not to be counted upon:

perhaps it has already vanished forever,

perhaps it will come back to me again,

although the circumstances of my life didn’t favour its return.

Thus I waver,

continually fly to the summit of the mountain,

but then fall back in a moment.

March 11, 1915 (p. 332)

Eastern and Western Jews, a meeting.

The Eastern Jews’ contempt for the Jews here.

Justification for this contempt.

The way the Eastern Jews know the reason for their contempt,

but the Western Jews do not.

March 13, 1915 (p. 333)

Occasionally I feel an unhappiness which almost dismembers me,

and at the same time am convinced of its necessity

and the existence of a goal to which one makes one’s way

by undergoing every kind of unhappiness

(am now influenced by my recollection of Herzen,

but the thought occurs on other occasions too.)

Franz Kafka – Letters to Friends, Family, & Editors (Translated by Richard and Clara Winston) – 1977 (1990) [Anthony Russo]

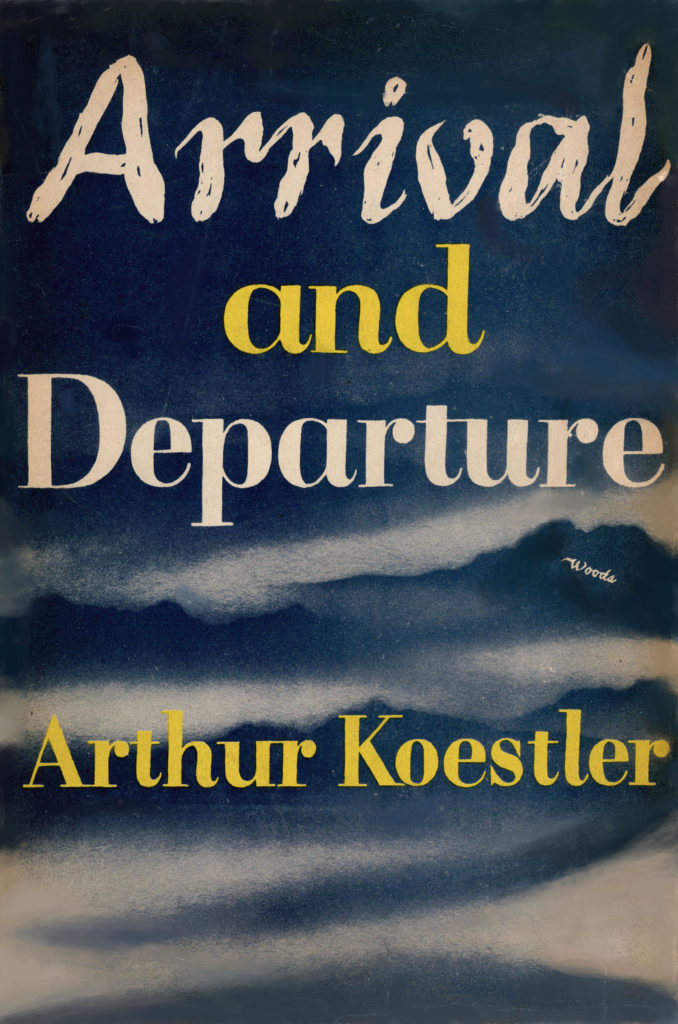

Arrival and Departure, by Arthur Koestler – 1943 [Wood]

What, after all, was courage?

A matter of glands, nerves; patterns of reaction conditioned by

heredity and early experiences.

A drop of iodine less in the thyroid,

a sadistic governess or over-affectionate aunt,

a slight variation in the electrical resistance

of the medullary ganglions,

and the hero became a coward;

a patriot a traitor.

Touched with the magic rod of cause and effect,

the reactions of men were emptied of their so-called moral contents

as a Leyden jar is discharged by the touch of a conductor.

‘Why do they look at me that way?’

‘Why do they look at me that way?’

‘They don’t look. It’s only your imagination.’

‘They ask themselves: What is he doing here?

Why does he not go where he belongs?’

‘But you belong nowhere, you fool.’

‘How can one live, belonging nowhere?’

‘You belong to yourself. That is the gift I made you.’

‘I don’t want it. Your gift is out of season.’

‘Then what do you want?’

‘Not to be ashamed of myself.’

‘What are you ashamed of?’

‘Of walking through the parks while others

get drowned or burned alive;

of belonging to myself while everybody belongs to something else.’

‘Do you still believe in their big words and little flags?’

‘No, I don’t.’

‘Are you not glad that I opened your eyes?’

‘Yes, I am.’

‘What were your beliefs?’

‘Illusions.’

‘Your search of fraternity?’

‘A wild goose chase.’

‘Your courage?’

‘Vanity.’

‘Your loyalty?’

‘Atonment.’

‘Why then do you want to start again?’

‘Why, indeed? That should be your job to explain.’

But that precisely was the point which Sonia could not explain,

for apparently it was placed on a plane beyond her reasoning,

and perhaps beyond reason altogether.

Don’t be a fool, said Sonia’s voice.

Don’t be a fool, said Sonia’s voice.

This is the ark and behind you is the flood.

That land is doomed and it will rain on it

forty nights and forty days.

Who has ever heard of an inmate of the ark

jumping overboard to walk back into the rising flood?

But why not, Sonia? There is something missing in that story.

There should have been at least one

who ran back into the rain,

to perish with those who had no planks under their feet…

Go on, said Sonia’s voice.

Go on, what happened to that fool after he went back?

The Lord who saw into that man’s heart became ashamed of himself;

and he reached out with his hand to keep that man dry in the rain…

* * * * * * * * * * * *

“Do you mean,” Peter stuttered,

“that you have done what you did – just as a sport?”

The other shrugged.

His attention was focused on the task of drinking from the glass

without spilling any of its contents.

“Don’t you think,” he said at last,

“that it is rather a boring game,

trying to find out one’s reasons for doing something?”