“And as Paul said these things to himself,

a wave of sadness washed over them as though they’d been written in sand.

He was understanding now that no man could live without roots

– roots in a patch of desert, a red clay field, a mountain slope, a rocky coast, a city street.

In black loam, in mud or sand or rock or asphalt or carpet,

every man had his roots down deep – his home.”

________________________________________

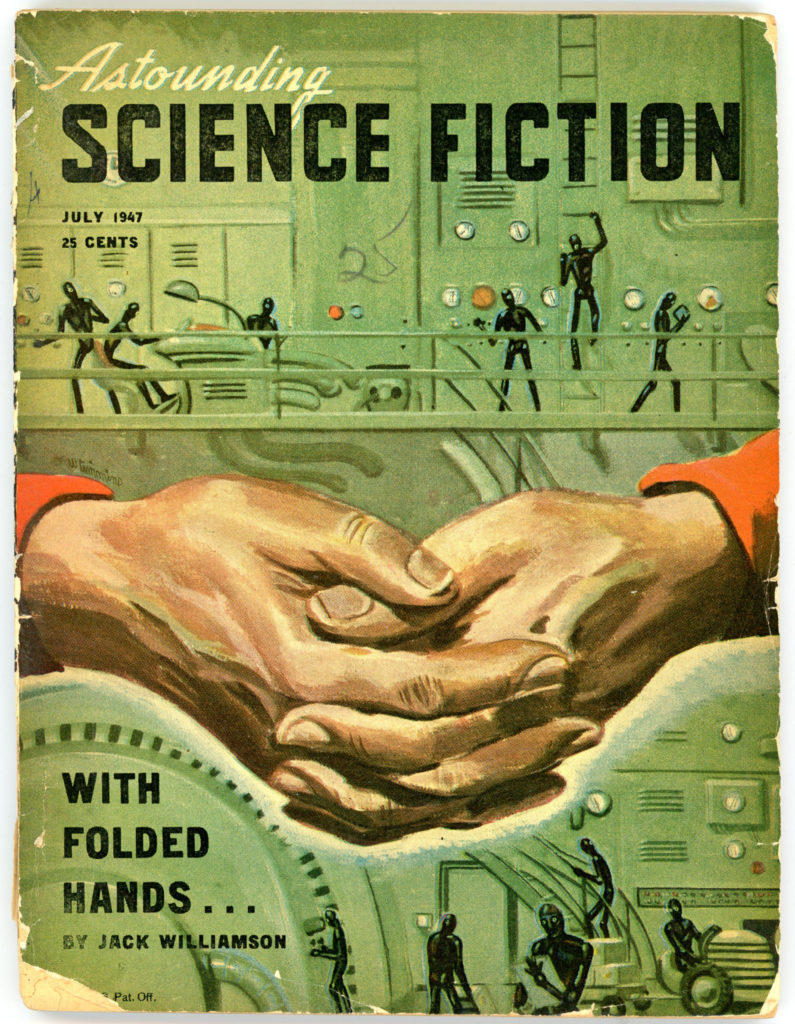

Some works of fiction are didactic: An author will compose a short story; a novelette; a novel, to impart a lesson or present a viewpoint about the nature of contemporary society through the vantage of a “world”, whether that world be past, present, or future; whether that world be real or purely imaginary.

Other works of fiction can be emotionally cathartic: They create moods of anticipation, dread, and fear; they manufacture a sense of unreality – a perhaps Lovecraftian unreality, one permeated by an inexpressible sense of wrongness: “That which should not be, but is!” The goal? To cause aN intensity of feeling through identification with a character‘s (or, characters’) predicament, and then the resolution of that predicament: hopefully for the good. And if not for the good, at least – if there’s any compensation to be had – with stoicism and bravery.

And, then, some works of fiction can be prophetic. Whether written a thousand, a hundred, or ten years “prior”; whether through chance; whether by calculatedly analyzing economic, ideological, sociological, and technological trends; whether by intuition born of a sixth sense, or, intuition born from the ability to view the “world” from a vantage point detached from popular culture and the mood of an age; whether ultimately by grasping (to adapt the idiom of Charles Péguy) the “mystique” of an age, some works of fiction can be – and are – windows upon the future.

The prediction doesn’t have to be accurate – how could it be? – close enough will duly suffice.

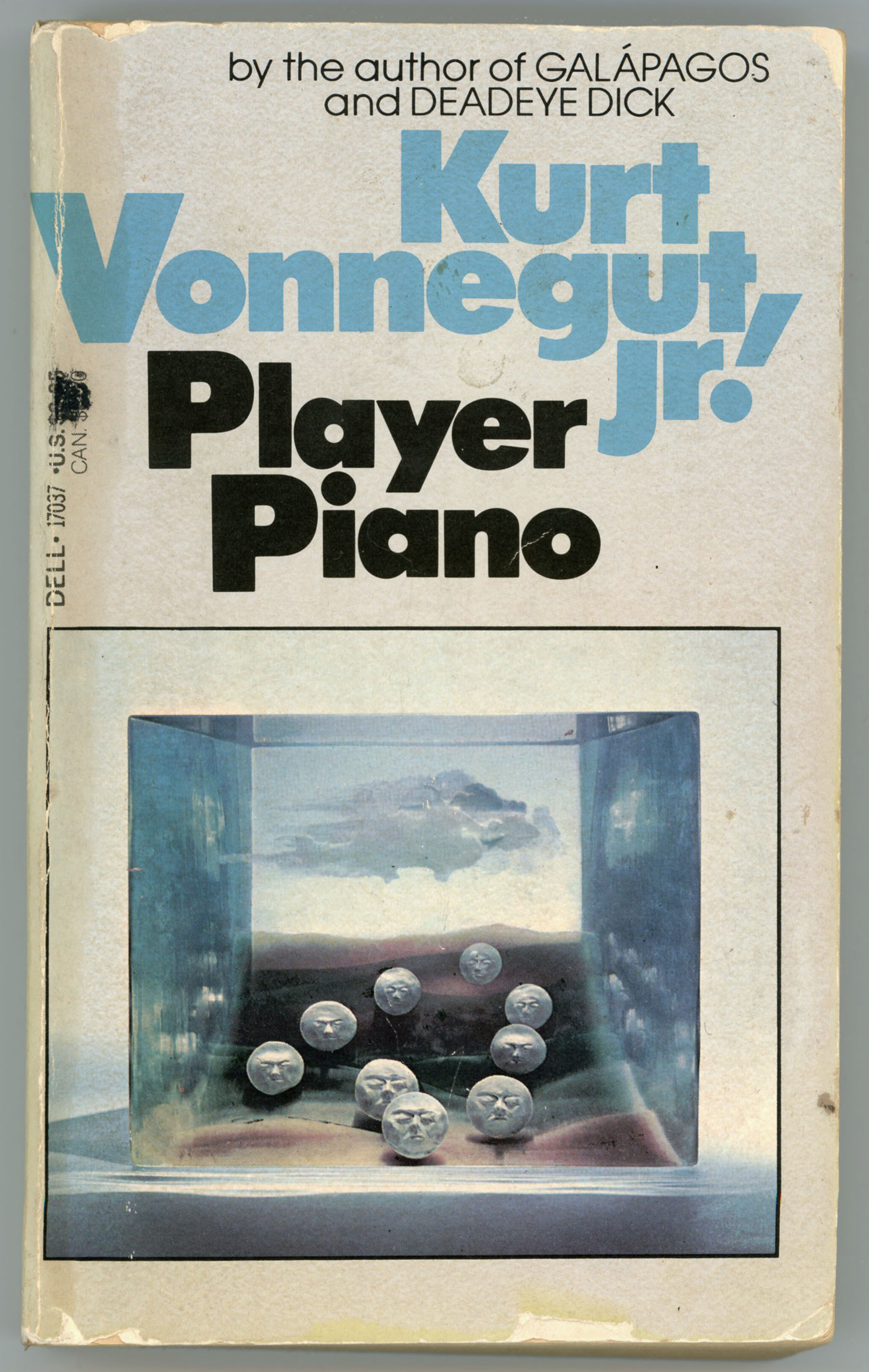

Case in point, Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.’s 1952 novel (his first novel, at that) Player Piano, excerpts from which follow, quoted from Dell’s 1980 edition.

Not as well known as his subsequent works, such as The Sirens of Titan or Slaughterhouse-Five (the latter having been adapted for film), the novel – especially in the year 2021 – merits consideration for Vonnegut’s degree of foresight, if not prescience, via his extrapolation of academic, sociological, and technological trends then prevalent in post WW-II America.

And today, irrevocably prevailing?

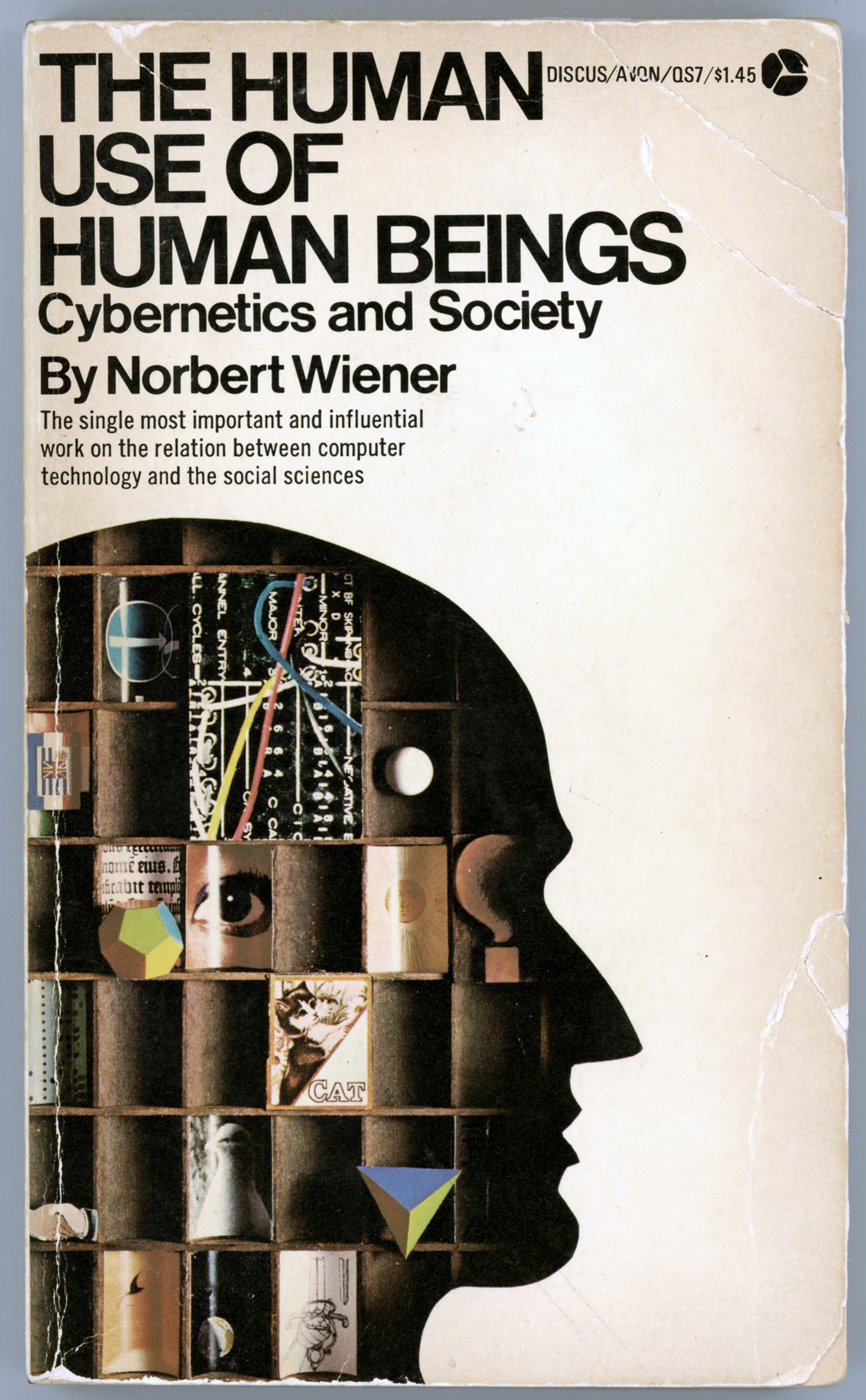

While an in-depth description of Player Piano is beyond the immediate scope of this post (such insight is readily available at Wikipedia and GoodReads), and it has been a “few” (!) decades since I’ve read the novel), here’s a mini(mini), highly simplified summary of the work: Vonnegut posits a scenario where in the United States, through a combination of advances in electronic technology, and, the development of a permanent academic, corporate, and government meritocracy, society has arrived at a great stagnation: A small minority (a very small minority) of corporate bureaucrats and electronic engineers has become responsible for the operation and maintenance of the technology that, in effect and reality, runs not just the United States, but the modern world.

On a technical note, the word “tapes” appears in the text when Vonnegut alludes to the technology and algorithms that run society, probably reflective of the use of magnetic tape as a medium for data storage in the 1950s. (Well, this was before the advent of the transistor, let alone integrated circuits.)

As touched upon at several points in the novel, the only real activity for many citizens has become “employment” with the Reconstruction and Reclamation Corps – the “Reeks and Wrecks” – or enrollment in the Army, the latter having no battles to fight. However, rather than the violence, rebellion, or “underground” one might expect to arise in such a situation, the mood and actions of the citizenry are instead characterized by the opposite: Except for the ruling elite, society is permeated by pervasive lethargy born of resignation: a spiritual, psychological, and intellectual malaise which has vague undertones (no overtones!) of a crudely Huxleyan – not Orwellian – world (by no means a Brave world, either). The material and physical needs of most of citizens are provided for on a nominal level, but humanity has become permanently “stuck”.

In this, the novel has similar characteristics to Kendell Foster Crossen’s Year of Consent, published by Dell in 1954. (Great cover art by Richard Powers.)

Enter Doctor Paul Proteus. (Great choice of character name by Vonnegut!) One of the “engineers”, the 35-year-old Dr. Proteus becomes disillusioned with and alienated from his place and role in society, and becomes involved in an attempt to … well … change things. Drastically. Permanently. For the better. However (spoiler alert!), despite his best efforts and the mood of optimism and hope that pervades the novel’s latter pages (you really, really think that success will ensue), Player Piano ends upon a solidly, matter-of-factly, pessimistic note: The organization of society, the pervasiveness and power of electronic technology, the reluctant or willing (and sometimes both) co-option of the intellectual elite by government and corporate (especially corporate) bureaucracy, and the habituation of the population to a gray nature, all combine to generate a civilizational momentum that has irrevocably solidified the structure of society.

Change, if any, will only come in a way yet unknown.

One recompense, though a recompense in a sense purely literary, is Player Piano’s very quality as literature. It’s well written. Very well written, at a level that renders its dystopian ending, well … uh … tolerable. In any event, not only is there no easy way out, there seems to be no way “out”, at all. And in that sense, another recompense, albeit of a symbolic nature, is that the novel’s ending is realistic and refreshingly non-Spielbergian, characterized by neither an avoidance of reality nor a romanticized view of human nature.

Examples of cover art for three editions of the book follow below, with quotes interspersed between.

________________________________________

Don’t you see, Doctor?” said Lasher.

“The machines are to practically everybody what the white men were to the Indians.

People are finding that, because of the way the machines are changing the world,

more and more of their old values don’t apply any more.

People have no choice but to become second-rate-machines themselves,

or wards of the machines.”

________________________________________

(Here’s the cover of the novel’s first (1952) printing; artist unknown. Note that the cover shows symbols of science and technology: An oscilloscope, a diagram of a circuit, and a “man”. Notably, the man – whether Scribner’s design staff intended so is unknown! – is dwarfed by technology.)

Paul nodded his thanks.

His skin began to itch, as though he had suddenly become unclean.

These were members of the Reconstruction and Reclamation Corps,

in their own estimate the “Reeks and Wrecks”.

Those who couldn’t compete economically with machines had their choice,

if they had no source of income,

of the Army or the Reconstruction and Reclamation Corps.

The soldiers,

with their hollowness hidden beneath twinkling buttons and buckles,

crisp serge, and glossy leather,

didn’t depress Paul nearly as much as the Reeks and Wrecks did. (21-22)

____________________

At one point, Kroner raised his big hand and asked if he might make a comment.

“Just to sort of underline what you’re saying, Paul,

I’d like to point out something I thought was rather interesting.

One horsepower equals about twenty-two manpower – big manpower.

If you convert the horsepower of one of the bigger steel-mill motors into terms of manpower,

you’ll find that the motor does more work than the entire slave population of the United States

at the time of the Civil War could do – and do it twenty-four hours a day.”

He smiled beatifically.

Kroner was the rock, the fountainhead of faith and pride for all in the Eastern Division. (45)

____________________

Kroner smiled, “As you say, like rabbits.

Incidentally, Paul, another interesting sidelight your father probably told you about

is how people didn’t pay much attention to this, as you call it,

Second Industrial Revolution for quite some time.

Atomic energy was hogging the headlines,

and everybody talked as though peacetime uses of atomic energy were going to remake the world.

The Atomic Age, that was the big thing to look forward to.

Remember, Baer?

And meanwhile, the tubes increased like rabbits.” (46-47)

(…and, rear cover.)

“Uh-huh,” said Paul, looking at the familiar graph with distaste.

It was a so-called Achievement and Aptitude Profile,

and every college graduate got one along with his sheepskin.

And the sheepskin was nothing, and the graph was everything.

When time for graduation came,

a machine took a student’s grades and other performances and integrated them into one graph

– the profile.

Here Bud’s graph was high for theory,

there low for administration,

here low for creativity, and so on, up and down across the page to the last quality

– personality.

In mysterious, unnamed units of measure,

each graduate was credited with having a high, medium, or low personality.

Bud, Paul saw, was a strong medium, as the expression went, personality-wise.

When the graduate was taken into the economy,

all his peaks and valleys were translated into perforations on his personal card. (65)

____________________

“That’s pretty strong.

I will say you’ve shown up what thin stuff clergymen were peddling, most of them.

When I had a congregation before the war,

I used to tell them that the life of their spirit in relation to God was the biggest thing in their lives,

and that their part in the economy was nothing by comparison.

Now, you people have engineered them out of their part in the economy,

in the market place, and they’re finding out

– most of them

– that what’s left is just another zero.

A good bit of enough, anyway.

My glass is empty.”

Lasher sighed. “What do you expect?” he said.

“For generations they’ve been built up to worship competition and the market,

productivity and economic usefulness, and the envy of their fellow men

– and boom! it’s all yanked out from under them.

They can’t participate, can’t be useful any more.

Their whole culture’s had been shot to hell.

My glass is empty.”

“I just had it filled again,” said Finnerty.

“Oh, so you did.” Lasher sipped thoughtfully.

“These displaced people need something, and the clergy can’t give it to them

– or it’s impossible for them to take what the clergy offers.

The clergy says it’s enough, and so does the Bible.

The people say it isn’t enough, and I suppose they’re right.”

“If they were so fond of the old system,

how come they were so cantankerous about their jobs when they had them?” said Paul.

“Oh, this business we’ve got now

– it’s been going on for a long time now, not just since the last war.

Maybe the actual jobs weren’t being taken from the people,

but the sense of participation, the sense of importance was.

Go to the library sometime,

and take a look at the magazines and newspapers clear back as far as World War II.

Even then there was a lot of talk about know-how winning the war of production

– know-how, not people, not the mediocre people running most of the machines.

And the hell of it was that it was pretty much true.

Even then, half the people or more didn’t understand much about the machines they worked at

or the things they were making.

They were participating in the economy all right,

but not in a way that was very satisfying to the ego.

And then there was all this let’s-not-shoot-Father Christmas advertising.”

“How that?” said Paul.

“You know – those ads about the American system,

meaning managers and engineers, that made America great.

When you finished one,

you’d think the managers and engineers had given America everything:

forests,

rivers,

minerals,

mountains,

oil

– the works.”

“Strange business,” said Lasher.

“This crusading spirit of the managers and engineers,

the idea of designing and manufacturing and distributing being sort of a holy way:

all that folklore was cooked up by public relations and advertising men

hired by managers and engineers to make big business popular in the old days,

which it certainly wasn’t in the beginning.

Now, the engineers and managers believe with all their hearts

the glorious things their forebears hired people to say about them.

Yesterday’s snow job business becomes today’s sermon.” (78-79)

____________________

And the personnel machines saw to it

that all governmental jobs of any consequence were filled by top-notch civil servants.

The more Halyard thought about Lynn’s fat pay check, the madder he got,

because all the gorgeous dummy had to do

was read whatever was handed to him on state occasions:

to be suitable awed and reverent,

as he said, for all the ordinary,

stupid people who’d elected him to office,

to run wisdom from somewhere else through that resonant voicebox

and between those even, pearl choppers. (104)

(The novel’s first paperback edition (November, 1954) published by Bantam Books under the title Utopia 14, with cover art by Charles Binger. The cover scene is so general as to be unrelated to any specific event in the novel. On one side and receding into the distance, an ambiguous mass of struggling humanity, with no individual distinct from another. On the other, a man stares forward contemplatively; indifferently. The backdrop? Towers, buildings, platforms, and perhaps a factory: A vague metropolis against a sunset.)

“Um,” said Mr. Haycox apathetically.

“What [sic] do you keep working so smoothly?”

Doctor Paul smiled modestly.

“I spent seven years in the Cornell Graduate School of Realty

to qualify for a Doctor of Realty degree and get this job.”

“Call yourself a doctor, too, do you?” said Mr. Haycox.

“I think I can say without fear of contradiction that I earned that degree,” said Doctor Paul coolly.

“My thesis was the third longest in any field in the country that year

– eight hundred and ninety-six pages, double-spaced, with narrow margins.”

“Real-estate salesman,” said Mr. Haycox.

He looked back and forth between Paul and Doctor Pond,

waiting for them to say something worth his attention.

When they’d failed to rally after twenty seconds, he turned to go.

“I’m doctor of cowshit, pigshit, chickenshit,” he said.

“When you doctors figure out what you want, you’ll find me in the barn shoveling my thesis.” (133-134)

____________________

He tried again:

“In order to get what we’ve got, Anita, we have, in effect,

traded these people out of what was the most important thing on earth to them

– the feeling of being needed and useful, the foundation of self-respect.” (151)

____________________

“That’s just it: things haven’t always been that way.

It’s new, and it’s people like us who’ve brought it about.

Hell, everybody used to have some personal skill or willingness to work

or something he could trade for what he wanted.

Now that the machines have taken over, it’s quite somebody who has anything to offer.

All most people can do is hope to be given something.” (159)

(And, the rather simple rear cover.)

“But he was great, and nobody’d argue about that,

but do you think he could have been great today, in this modern day and age?

Wheeler? Elm Wheeler?

You know what he would be today?

A Reek and a Wreck, that’s all.

The war made him, and this life would of killed him.”

“Used to be there was a lot of damn fool things a dumb bastard could do to be great,

but the machines fixed that.

You know, used to be you could go to sea or a big clipper ship or a fishing ship

and be a big hero in a storm.

Or maybe you could be a pioneer and go out west and lead the people

and make trails and chase away Indians and all that.

Or you could be a cowboy, or all kinds of dangerous things, and still, be a dumb bastard.

“Now the machines take all the dangerous jobs,

and the dumb bastards get tucked away in big bunches of prefabs

that look like the end of a game of Monopoly, or in barracks,

and there’s nothing for them to do but set there

and kind of hope for a big fire

where maybe they can run into a burning building in front of everybody

and run out with a baby in their hands.

Or maybe hope

– though they don’t say so out loud because the last one was so terrible

– for another war.

Course, there isn’t going to be another one.

“And, oh, I guess machines have made things a lot better.

I’d be a fool to say they haven’t,

though there’s been plenty who say they haven’t,

and I can see what they mean, all right.

It does seem like the machines took all the good jobs,

where a man could be true to himself and false to nobody else, and left all the silly ones.

And I guess I’m just about the end of a race, standing here on my own two feet.” (178-179)

____________________

“Paul, your father tells me you’re real smart.”

Paul had nodded uncomfortably.

“That’s good, Paul, but that’s not enough.”

“No, sir.”

“Don’t be bluffed.”

“No, sir, I won’t.”

“Everybody’s shaking in their boots, so don’t be bluffed.”

“No, sir.”

“Nobody’s so damn well educated that you can’t learn ninety per-cent of what he knows in six weeks. The other ten per cent is decoration.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Show me a specialist,

and I’ll show you a man who’s so scared he’s dug a hole for himself to hide in.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Almost nobody’s competent, Paul.

It’s enough to make you cry to see how had most people are at their jobs.

If you can do a half-assed job of anything, you’re a one-eyed man in the kingdom of the blind.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Want to be rich, Paul?”

“Yes, sir – I guess so. Yes, sir.”

“All right. I got rich, and I told you ninety per cent of what I know about it.

The rest is decoration. All right?” (198)

(One of the several paperback editions published by Dell, this copy is a 1980 imprint. Hard to tell if the cover design is a painting, or, a sculpture or casting; I think the latter. Faces – similar faces – embedded in clear acrylic or glass. Looks like a human pinball machine, where the pinballs are frozen in space.)

And as Paul said these things to himself,

a wave of sadness washed over them as though they’d been written in sand.

He was understanding now that no man could live without roots

– roots in a patch of desert, a red clay field, a mountain slope, a rocky coast, a city street.

In black loam, in mud or sand or rock or asphalt or carpet,

every man had his roots down deep – his home.

A lump grew in his throat, and he couldn’t do anything about it.

Doctor Paul Proteus was saying goodbye forever. (205)

____________________

“Public relations,” said Halyard.

“Please, what are public relations?” said Khashdrahr.

“That profession,” said Halyard, quoting by memory from the Manual,

“that profession specializing in the cultivation,

by applied psychology in mass communication media,

of favorable public opinion with regard to controversial issues and institutions,

without being offensive to anyone of importance,

and with the continued stability of the economy and society its primary goal.” (209)

____________________

“… He watched his brother find peace of mind through psychiatry.

That’s why he won’t have anything to do with it.”

“I don’t follow. Isn’t his brother happy?”

“Utterly and always happy.

And my husband says somebody’s just got to be maladjusted;

that somebody’s got to be uncomfortable enough to wonder where people are,

where they’re going,

and why they’re going there.

That was the trouble with his book.

It raised those questions, and, was rejected.

So he was ordered into public-relations duty.” (212)

(And, rear cover.)

Don’t you see, Doctor?” said Lasher.

“The machines are to practically everybody what the white men were to the Indians.

People are finding that, because of the way the machines are changing the world,

more and more of their old values don’t apply any more.

People have no choice but to become second-rate-machines themselves,

or wards of the machines.” (251)