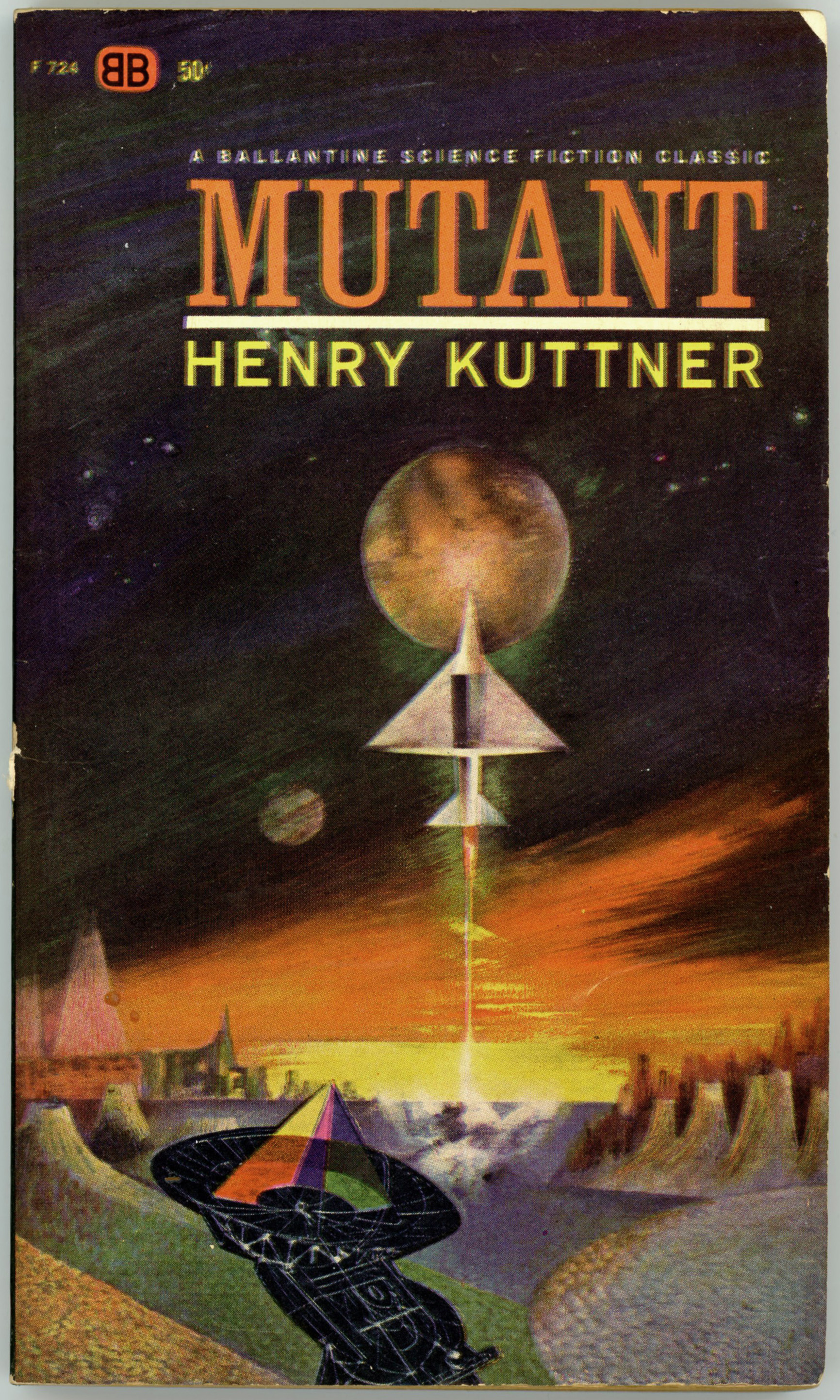

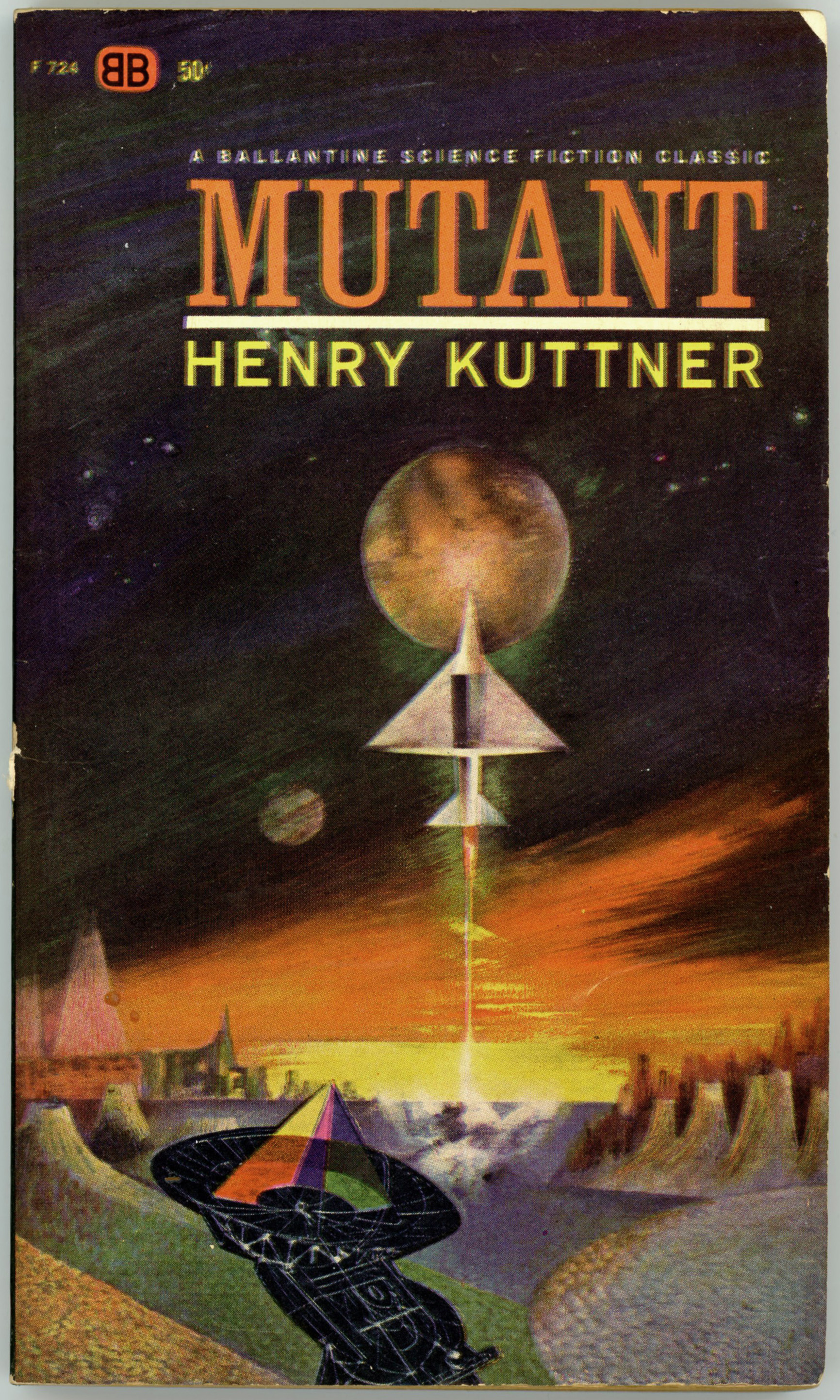

This cover, for Ballantine’s 1963 edition of Henry Kuttner’s Mutant, is a bit of a mystery: The artist’s name is absent from both the book’s exterior and interior, while his (her?) identity is similarly absent in the Internet Speculative Fiction Database.

The radio telescope at the bottom of the cover appears in a style – simple lines and bold colors – somewhat akin to that seen in the works of wildlife artist Charley Harper. But, there’s no way to tell, for sure. Regardless, though the cover is certainly not the most striking science-fiction paperback cover, it is representative of the genre’s art of the early 1960s.

On a side note, only after scanning the cover was it noticed that the cover art – specifically the very text “A Ballantine Science Fiction Classic”, “Mutant”, and “Henry Kuttner” – were all printed out of alignment. (Oops!)

Otherwise, curiously, while the author’s name is given on the cover as Henry Kuttner, within the issues of Astounding Science Fiction where the book’s five stories first appeared, the author’s name is given as – “Lewis Padgett” – the pen-name for the collaborative efforts of Henry Kuttner and his wife, Catherine L. Moore (the latter, one of my favorite authors).

Here’s a close-up of the radio telescope…

Here’s a close-up of the radio telescope…

Contents (credited to Lewis Padgett)

Contents (credited to Lewis Padgett)

The Piper’s Son, from Astounding Science Fiction, February, 1945

Three Blind Mice, from Astounding Science Fiction, June, 1945

The Lion and The Unicorn, from Astounding Science Fiction, July, 1945

Beggars in Velvet, from Astounding Science Fiction, December, 1945

Humpty Dumpty, from Astounding Science Fiction, September, 1953

The cover art of the original, hardcover, Gnome Press, Inc., edition of Mutant is show below, while the descriptive text inside the front and rear covers follows. Note that this cover was done by the (relatively) little-known Ric Binkley, who created the cover art for the 1953 Gnome Press edition of Isaac Asimov’s Second Foundation. (This image was found via a web search, thus, this particular book, unlike the great majority displayed at this blog, isn’t actually in my collection.) A small reproduction of this cover also appears on page 195 of Brian Ash’s 1977 The Visual Encyclopedia of Science Fiction.

The cover art of the original, hardcover, Gnome Press, Inc., edition of Mutant is show below, while the descriptive text inside the front and rear covers follows. Note that this cover was done by the (relatively) little-known Ric Binkley, who created the cover art for the 1953 Gnome Press edition of Isaac Asimov’s Second Foundation. (This image was found via a web search, thus, this particular book, unlike the great majority displayed at this blog, isn’t actually in my collection.) A small reproduction of this cover also appears on page 195 of Brian Ash’s 1977 The Visual Encyclopedia of Science Fiction.

From jacket of hardcover edition…

From jacket of hardcover edition…

Sometime during the next century a mutant will crash high up in a chain of snowcapped mountains.

He will crawl from the wreckage of his ship,

frown at the jagged ridge of cliffs that surrounds him,

and then send out his thoughts, probing,

seeking he reassuring touch of the minds which unite with his to give life its fullest meaning.

And he will touch … nothing … but the echoing emptiness of his own isolated thoughts.

Alone.

He will lie in the snows, delirious, semi-conscious,

and try to keep from freezing by calling up,

from the deepest wells of his race’s memories,

the cherished stories of the great Baldy minds who led their kind out of the valley of danger.

And he will remember, as though it happened before his weary eyes,

how the great Blowup came and wiped out mankind’s civilization almost overnight,

leaving only huge radioactive sores (the graves of cities) over the face of the earth.

How, near these shunned areas, were born the first Baldies,

hated and feared by normal human survivors

because they were completely hairless and telepathic.

In his delirium the castaway will relive the tense lives of the first sane Baldies,

like Al Burkhalter, who tried to live peacefully

by wearing a big smile and respecting the intimate privacy of their minds.

How other menacing Baldies appeared, paranoids,

who insisted that all the normal humans must be wiped out for the survival of the Baldy race.

He will recall how this incredibly tense,

secret struggle between the sane and paranoid Baldies threatened,

at any time,

to ignite the great pogrom – the wiping out of all Baldies by the normal kind.

And how this silent conflict gave meaning to the life of the piper’s son;

to David Barton, Baldy naturalist, collector of big and little game,

who had to destroy the menace of the three blind mice;

to McNey who found a way to combat the powerful paranoids and died to conceal it;

to Harry Burkhalter, grandson of Al Burkhalter,

who became a Mute to aid his people’s cause when the great pogrom took place;

and to the Baldies who sought desperately for the means to give the power of telepathy –

the Baldy’s cross, and yet his crown – to the normal humans,

so that both kinds might live peaceful and trusting lives.

The mutant will life frozen in the mountain-snows

and know the outcome of that great attempt as his life fades like a dying flame

and as rescuing helicopters descend to extend a helping hand.

– MUTANT is probably one of the most important and skillful science fiction novels written yet by a contemporary author.

______________________________

And, Mutant’s rear cover, showing 1953 prices for books written by such authors as Arthur C. Clarke (Against the Fall of Night), Hal Clement (Iceworld), Isaac Asimov (Second Foundation), Clifford D. Simak (City), and A.E. van Vogt (The Mixed Men), as well as several anthologies.

All between $2.50 and $3.95…! (? – !)

References

References

Mutant, at Internet Speculative Fiction Database

Ash, Brian (editor), The Visual Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, Harmony Books, New York, N.Y., 1977

“When the drugs and the television were perfected by the computers that made and distributed them, the cars were no longer necessary.

“When the drugs and the television were perfected by the computers that made and distributed them, the cars were no longer necessary.