SECURITY

A.D.

1990

“It is only 36 years from now.

The streets, the buildings, the fields look just as they do today.

And the people look the same

– until you get close enough to see the bland, vacant stare in their eyes,

to hear the empty, guarded quality of their voices.”

______________________________________

“His faith was the faith of a Torquemada backed by science.”

____________________

The imagination of the future comes in many guises.

Among the most compelling are five twentieth-century novels that, despite the marked differences in their literary styles, plot, and characters, are stunning examples of world-building. All are chillingly crisp depictions of totalitarianism built upon a foundation of technology and bureaucracy, and ultimately, sociological persuasion, manipulation, and control.

1984, by George Orwell

Brave New World, by Aldous Huxley

Fahrenheit 451 (based on The Fireman) by Ray Bradbury

We, by Evgeniy Zamyatin

Utopia 14 (alternate title Player Piano), by Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.

There are innumerable other works in this vein, particularly in the realm of science-fiction, which have received (or merited?!) far less attention, but which are still compelling in their own right. One of these is Kendell Foster Crossen’s 1954 Year of Consent which, despite not being of the same literary standard as the above-mentioned works, has proven to be eerily relevant to the United States, and perhaps “the world”, of 2021. A Dell paperback, you can read David Foster’s insightful 2021 review – I recommend it highly! – at ChicagoBoyz, and three brief comments (with middling ratings; oh, well!) at GoodReads.

To quote David Foster’s post:

The story is set in the then-future year of 1990. The United States is still nominally a democracy, but the real power lies with the social engineers…sophisticated advertising & PR men…who use psychological methods to persuade people that they really want what they are supposed to want. (Prefiguring “nudging”) The social engineers are aided in their tasks by a giant computer called Sociac (500,000 vacuum tubes! 860,000 relays!) and colloquially known as ‘Herbie.’ The political system now in place is called Democratic Rule by Consent. While the US still has a President, he is a figurehead and the administration of the country is actually done by the General Manager of the United States….who himself serves at the pleasure of the social engineers. The social engineers work in a department called ‘Communications’, which most people believe is limited to such benign tasks as keeping the telephones and the television stations in operation. Actually, its main function is the carrying out of influence operations.

…and…

Year of Consent can’t be called great literature, on a par with 1984 or Brave New World, but it projects a future which is perhaps closer to the immediate threats facing American liberty in 2020 than do either of those two other novels.

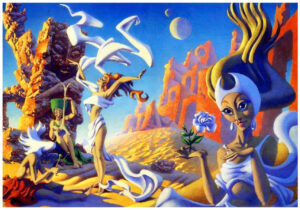

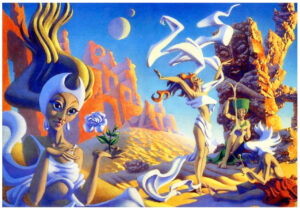

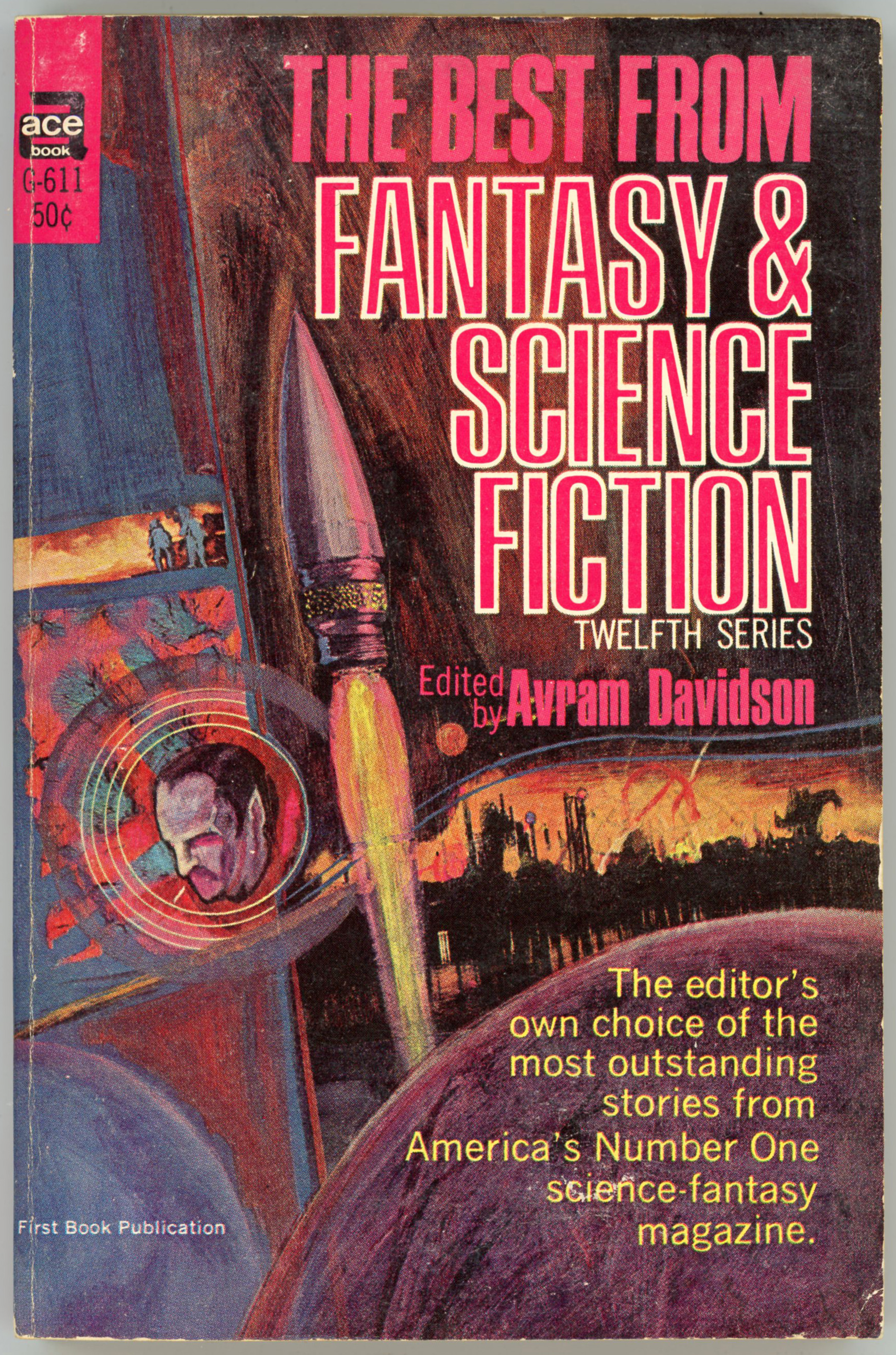

Aside from Crossen’s prescience, in purely artistic terms, Dell’s paperback is an unusual example of the art of illustrator Richard Powers. Unlike as in the overwhelming majority of his compositions, Powers created a painting that is both symbolic and realistic. In the background, kind of Matrix-like, a citizen is embedded in and connected to electronic circuits, her hands and feet fused into or hidden by a tapestry of wire junctions, even as her head and torso are surrounded by a translucent container.

However… Protagonist Gerald Leeds an his girlfriend Nancy are neither stylized nor abstract nor – as in so many of Powers’ 1950s paintings – diminutively symbolic: They’re depicted in complete and dramatic realism as they flee from “Herbie”.

____________________

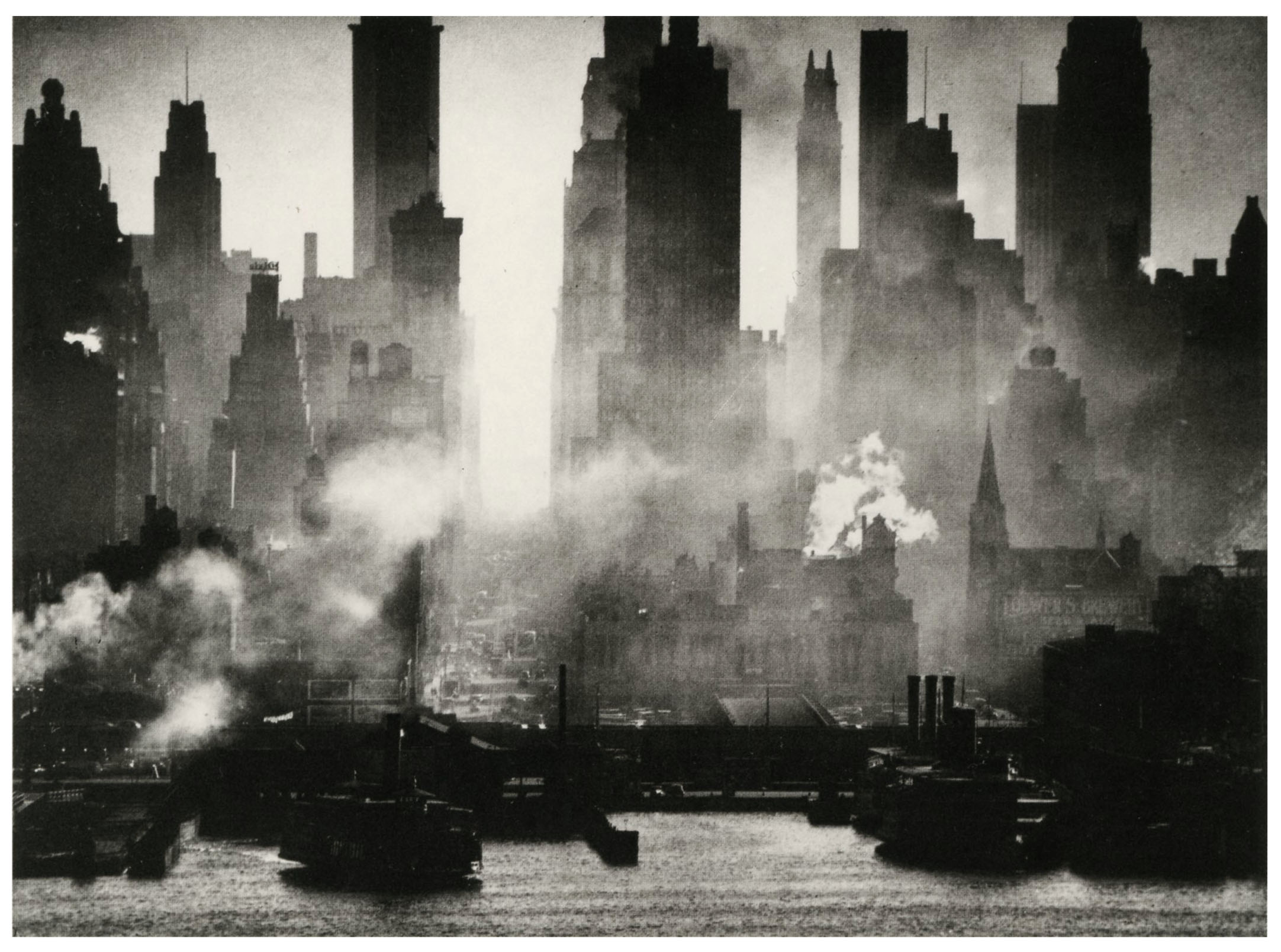

She and her smartphone are one!

____________________

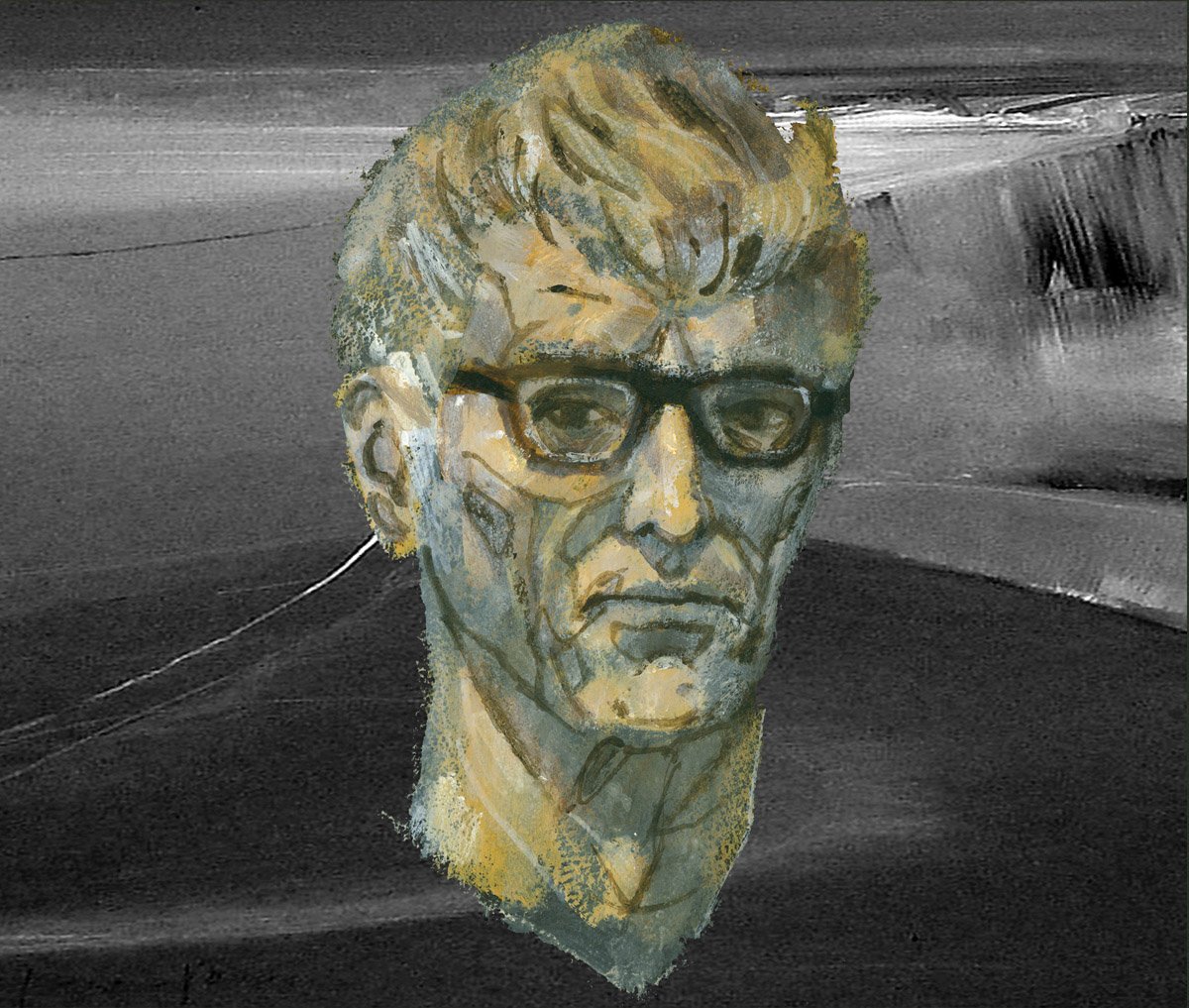

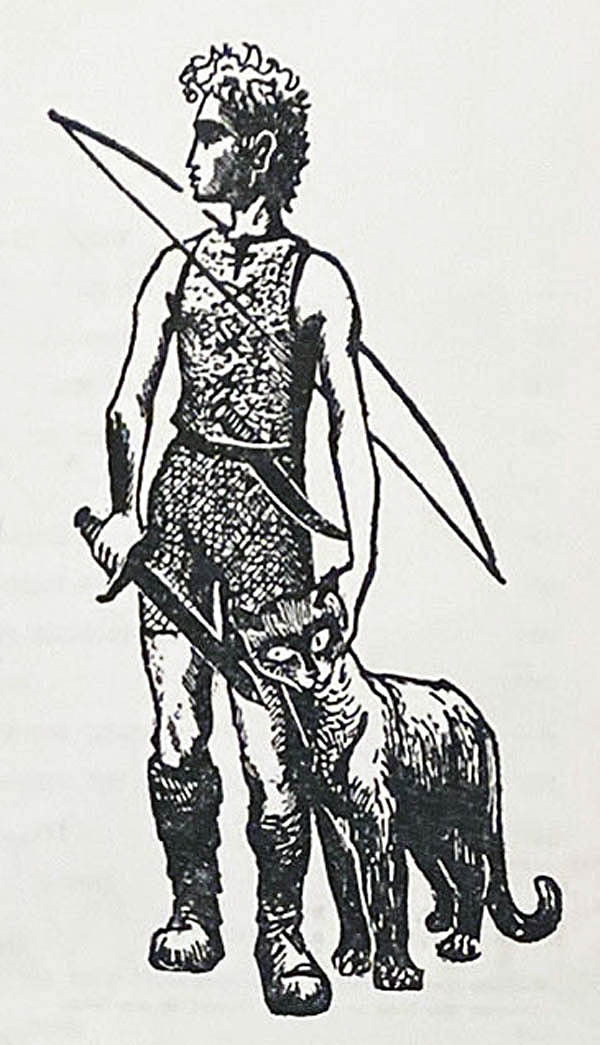

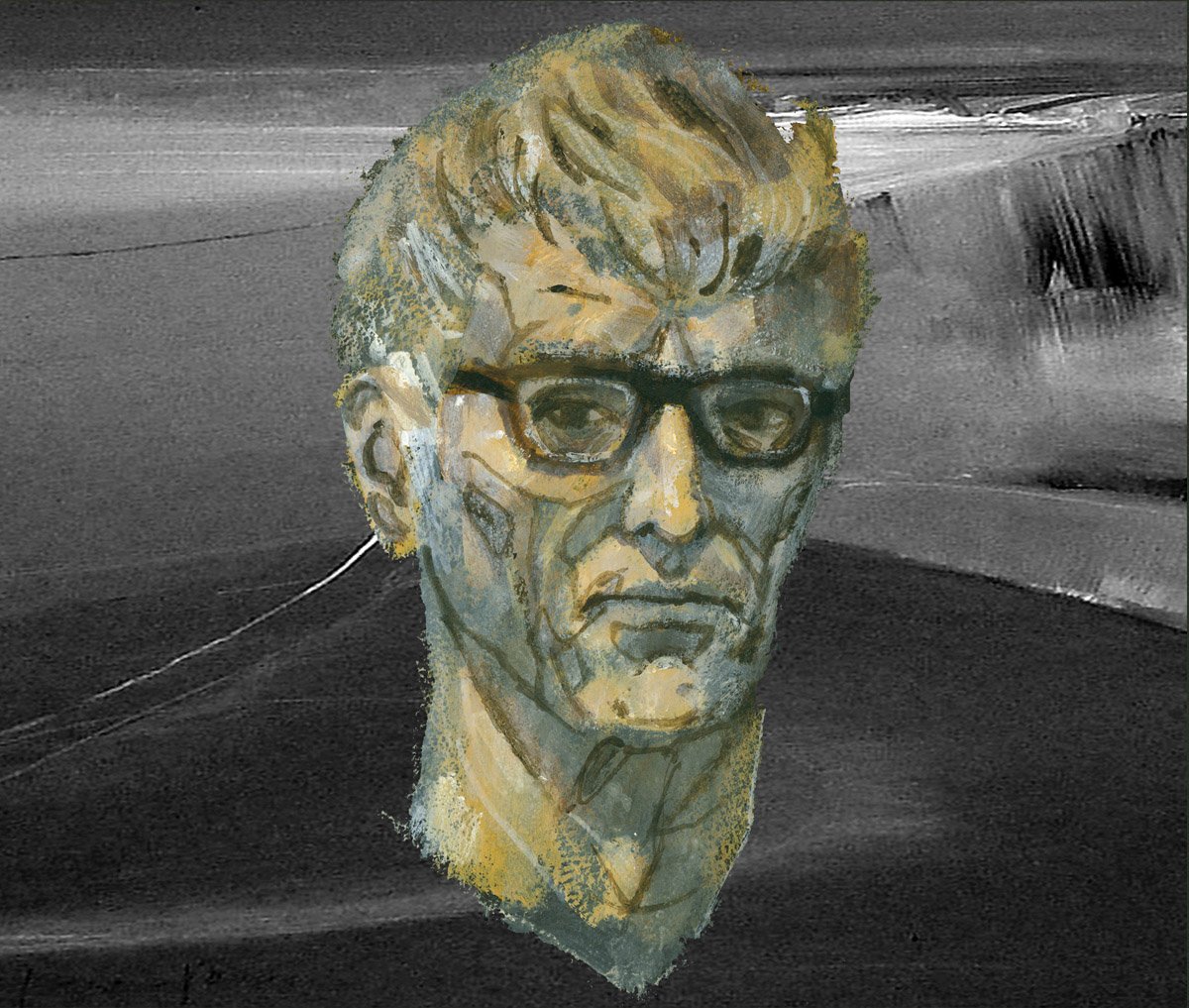

As far as the appearance of Gerald Leeds, could he have been modeled after Powers himself, as in this self-portrait from Bill & Sue-On Hillman’s ERBZine? (Just a thought.)

____________________

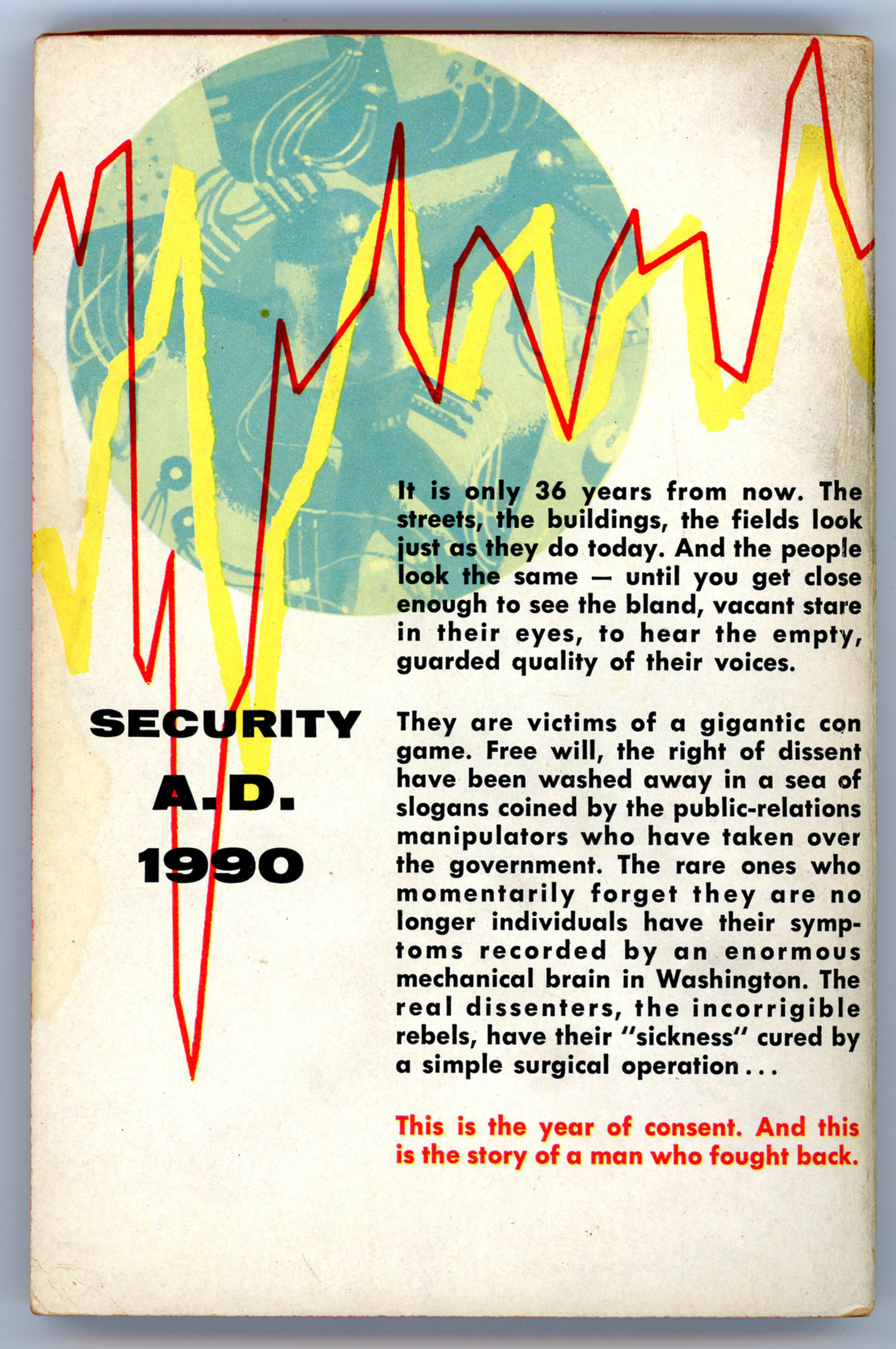

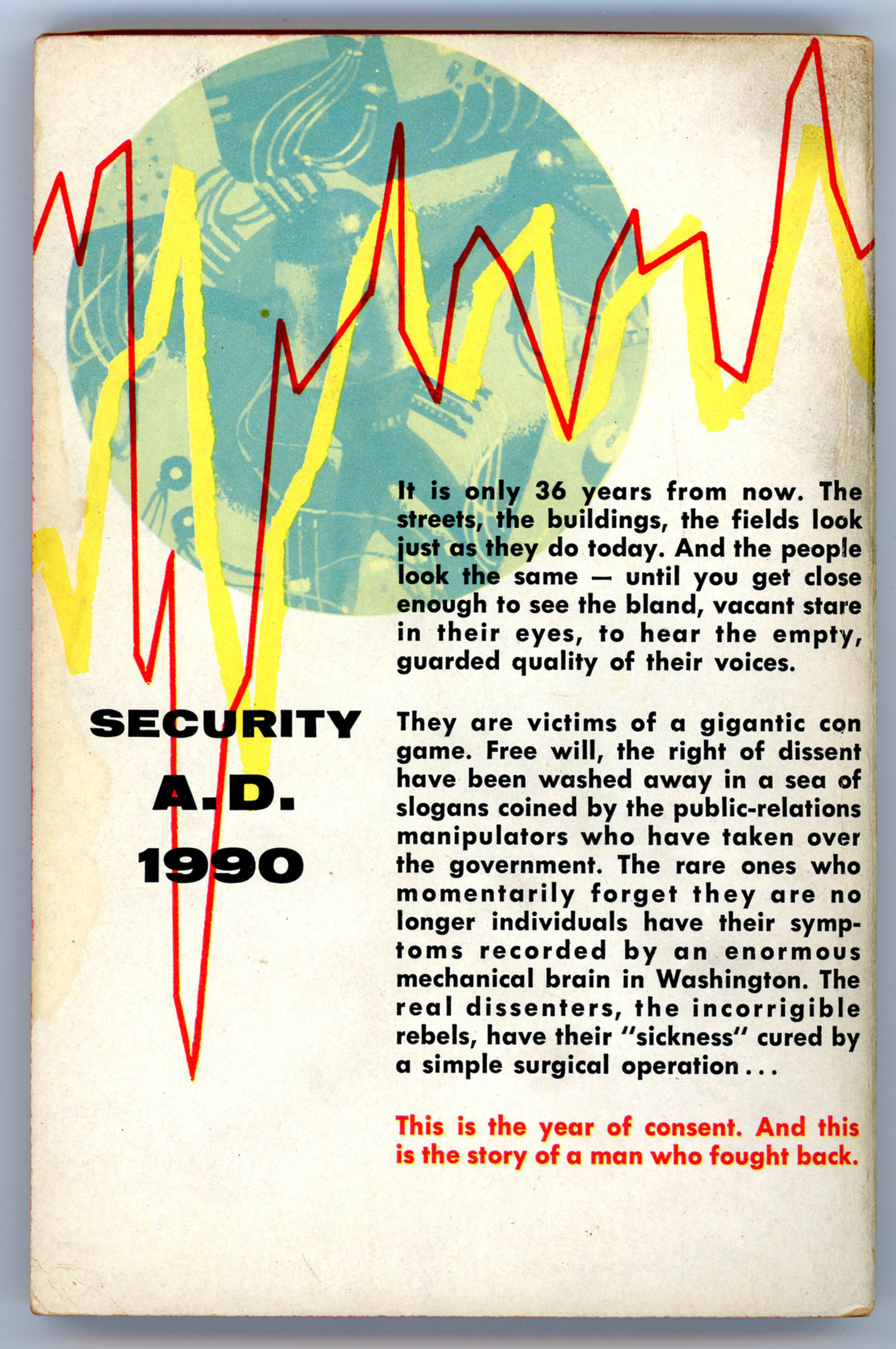

SECURITY A.D. 1990

It is only 36 years from now. The streets, the buildings, the fields look just as they do today. And the people look the same – until you get close enough to see the bland, vacant stare in their eyes, to hear the empty, guarded quality of their voices.

They are victims of a gigantic con game. Free will, the right of dissent have been washed away in a sea of slogans coined by the public-relations manipulators who have taken over the government. The rare ones who momentarily forget they are no longer individuals have their symptoms recorded by an enormous mechanical brain in Washington. The real dissenters, the incorrigible rebels, have their “sickness” cured by a simple surgical operation…

This is the year of consent. And this is the story of a man who fought back.

____________________

____________________

Some quotes from the novel.

Or, are they aspects of our reality?

____________________

Never has there been more freedom anywhere than in America today.

We’ve done away with police and even prisons.

Crime has been almost wiped out since we recognized it as a social disease.

We’ve done away with poverty.

There are fewer restrictions on people than ever before in the history of mankind.

For the first time they’re really free.

Gerald reflects:

Even if it hadn’t been dangerous, I wouldn’t have argued with him.

He believed what he was saying.

His faith was the faith of a Torquemada backed by science.

There was no way to make him see

that the social engineers had taken away only one freedom,

but that it was the ultimate freedom –

the right to choose.

Everything…was decided for them and then they were conditioned to want it.

____________________

“Why even the great Lenin said,

“It is true that liberty is precious – so precious that it must be rationed.”

“Yeah,” I said dryly. “Hobbyhorses.”

“What?”

“Hobbyhorses,” I repeated.

“Did you know that it is now almost two generations

since hobbyhorses have been sold in toy stores in either Russia or the United States?”

“I’m afraid I don’t understand,” he said doubtfully.

“I’m not sure why hobbyhorses withered away in the Soviet,” I said,

“but the ban was started here by the playschool consultants,

who were influenced by the social engineers

long before the latter came into power.

They put the finger on hobbyhorses

on the grounds that they did not develop the group spirit.”

He nodded thoughtfully.

“Of course.

But you realize that it meant different things in the two countries.

Here the group spirit was used to build fascism

while in Russia and the Soviet Countries it was used to build a people’s world.

____________________

This is a fight to the finish between mass man and individual man.

It was a pretty even match until the advent of controlled mass communications.

Then the giant electronic brains completely tipped the scales…

there is no difference between our social engineers and those in Russia.

Both are out to turn the world into one of mass men –

everyone conforming in every single way.

And they’ve damn near succeeded.

____________________

____________________

References

Chicagoboyz

…at Chicagoboyz.net

The Brothers Karamazov

…at Project Gutenberg

“The Grand Inquisitor” (translated by H.P. Blavatsky)

…at OnLine Literature

Kendell Foster Crossen

…at Internet Speculative Fiction Database

…at The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction

… at Fantastic Fiction

…at Wikipedia

…at Project Gutenberg (“The Gnome’s Gneiss”, and, “The Ambassadors From Venus”)

Evgeniy Ivanovich Zamyatin

…at Internet Speculative Fiction Database

Official Edgar Rice Burrough’s Tribute and Weekly Webzine Site

…at erbzine.com