In February of 2018, I created a post showing Edd Cartier’s interior art associated with Eric Frank Russell’s Sinister Barrier, which appeared in the first (October, 1939) issue of Unknown, featuring great allegorical cover art by Harold Winfield Scott. Not having a physical copy of the magazine, I did this via a CBR copy accessed via the Pulp Magazine Archive.

A few months ago, I symbolically “revisited” Russell’s story through a visit to the New York Public Library (the one with the two lions – Patience and Fortitude – out front), and was able to examine a near-mint physical – not merely pixel! – copy of Fantasy Press’s 1948 edition of the book. As I did with Jack Williamson’s Darker Than You Think, I copied this edition’s interior art – again by Edd Cartier – by means of a (relatively) antique but entirely effective digital SLR. The resulting images – edited somewhat with Photoshop Elements – are show below. Enjoy. (And, watch out for those gnasty Vitons! Y’never know where they’ll turn up next!)

The Fantasy Press edition features an illustration by A.J. (Andrew Julian) Donnell, which appears in simplified form for every chapter heading.

Oh, as for the novel itself, as a literary work? Long curious about the story, particularly in light of Unknown’s cover art, I read it just a few years ago, in the form of the 1966 Paperback Library edition. (See the “bottom” of this post.) It’ll suffice to say that though the book’s plot is interesting – enough – as the basis for a literary work, it was not the most impactful read, and I do not at all plan to revisit it, unlike the works of authors such as Cordwainer Smith, C.L. Moore, and Philip K. Dick, which never grow repetitive regardless of reading. Certainly the action moved swiftly and the flow of events accelerated through the story. Certainly Russell was a competent enough wordsmith to craft a well-structured story. Certainly he was able to generate a dark and forbidding “feel”; a near-paranoid atmosphere (curiously akin to the open chapters of The Three-Body Problem, where occurs an ominous and perplexing flurry of unexplained suicides of prominent scientists); an initially hopeless “mood” in his book, which suited the challenge of first identifying, then evading, and then fighting, and finally conquering, the Viton menace. But, the absence of any real complexity to his characters, coupled with really weird (truly weird, man!) literary habits (such as substituting the word “optics” for “eyes” – what? why?!) left the story with a feeling a flatness.

Entertaining and diverting – yes; weighty and enthralling enough for another read – no.

Nonetheless, the art’s great!

“An iridescent blue closed upon him and formed a satanic nimbus behind his head.”

(Frontispiece)

“An awful pillar that reached to the very floors of heaven…”

(Page 63)

“Others crept or-slunk through the alleys and the shadows…”

(Page 139)

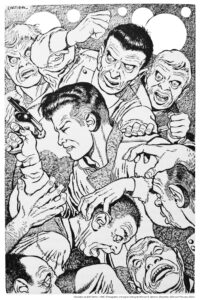

“A thousand hands seemed to be reaching for him at once.”

(Page 232)

Every chapter commences with an image akin to the front cover, showing Vitons hovering over a helpless, crouching figure. Here’s the header image for Chapter 11.

Published in 1950 by World Editions, Inc., Sinister Barrier was the first of Galaxy’s forty-six Science Fiction Novels. Cover by David Stone.

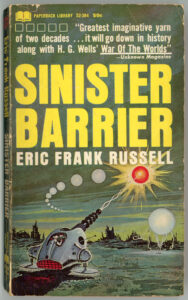

The first Paperback Library imprint having been May, 1964, here’s the company’s December, 1966 edition of Sinister Barrier. Though the book’s cover artist remains unnamed in the Internet Speculative Fiction Database (the cover’s absent of signature or initials), if one plays the “…it looks like…” game, the painting resembles the work of Ed Valigursky. (Just an idea.)

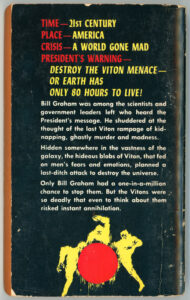

Rear cover. Straightforward prose.

TIME – 21ST CENTURY

PLACE – AMERICA

CRISIS – A WORLD GONE MAD

PRESIDENT’S WARNING –

DESTROY THE VITON MENACE

OR EARTH HAS

ONLY 80 HOURS TO LIVE!

Bill Graham was among the scientists and

government leaders left who heard the

President’s message. He shuddered at the

thought of the last Viton rampage of

kidnapping, ghastly murder and madness.

Hidden somewhere in the vastness of the

Galaxy, the hideous blobs of Viton, that fed

on men’s fears and emotions, planned a

last-ditch attack to destroy the universe.

Only Bill Graham had a one-in-a-million

chance to stop them. But the Vitons were

so deadly that even to think about them

risked instant annihilation.