Here, in this house, you shall meet the first sketch of the real God.

It is a man — or a being made by man —

who will finally ascend the throne of the universe.

And rule forever.

__________

No, no; we want geldings and oxen.

There will never be peace and order and discipline so long as there is sex.

When man has thrown it away, then he will become finally governable.

__________

But the educated public, the people who read the highbrow weeklies,

don’t need reconditioning.

They’re all right already.

They’ll believe anything.

______________________________

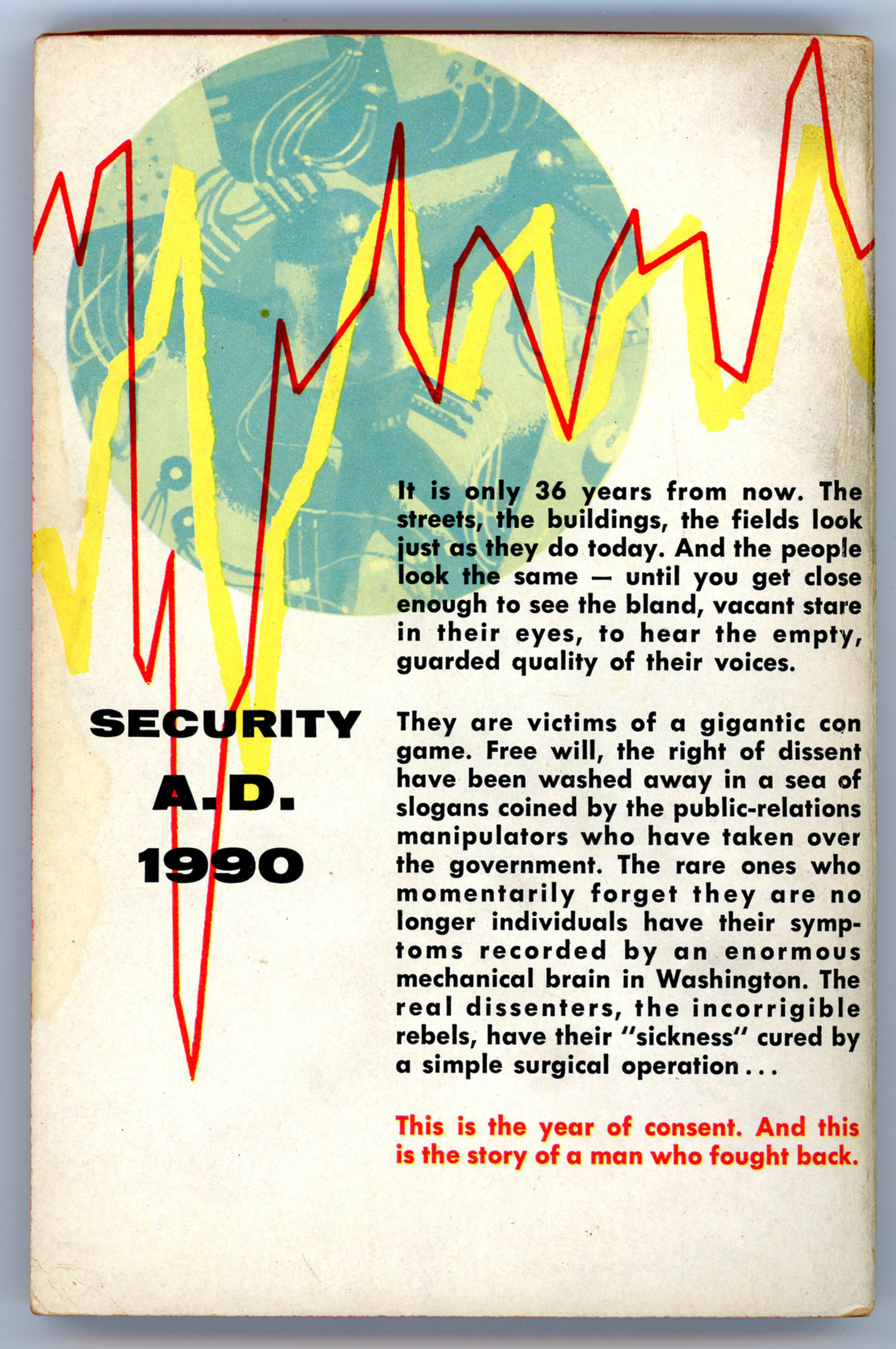

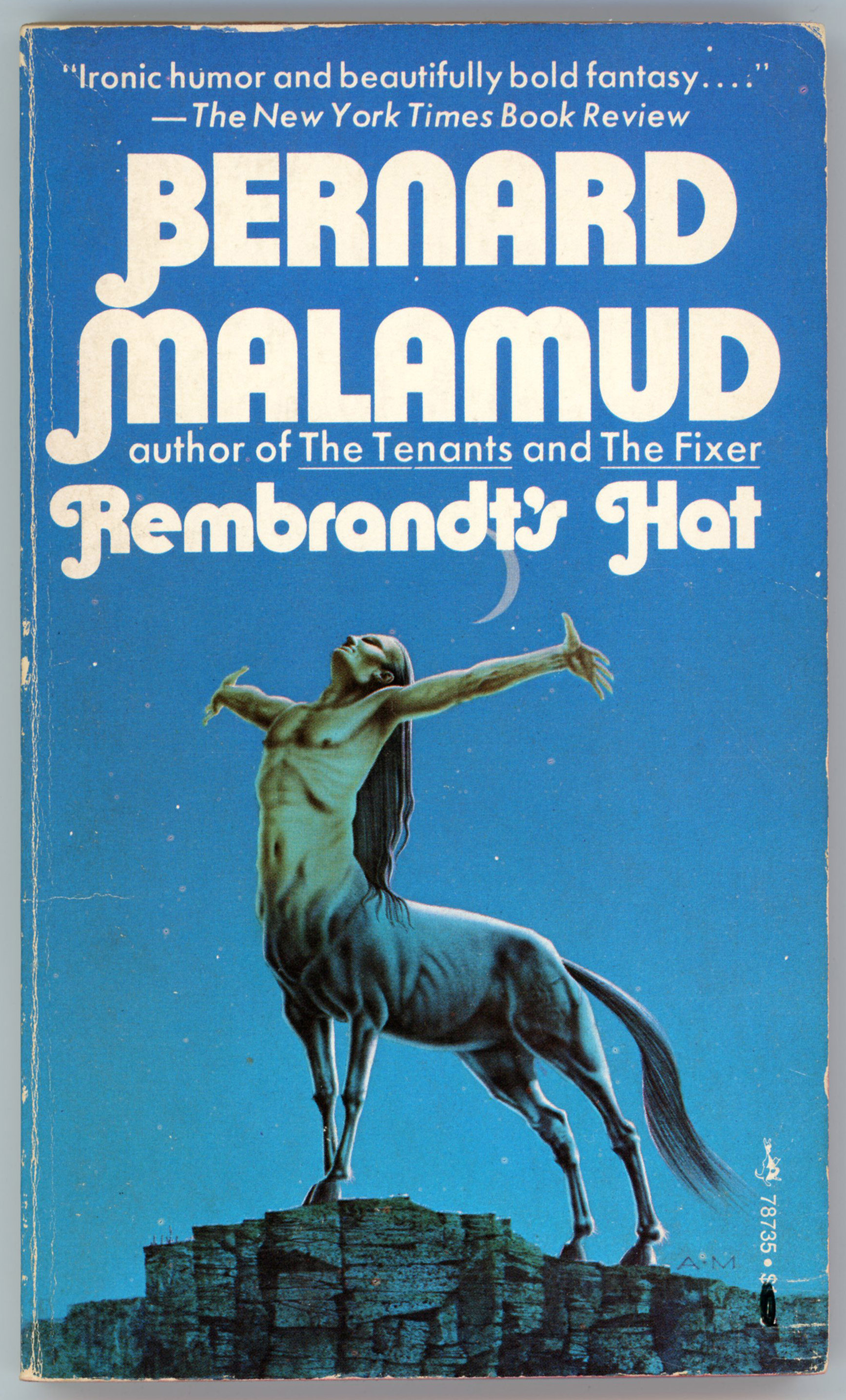

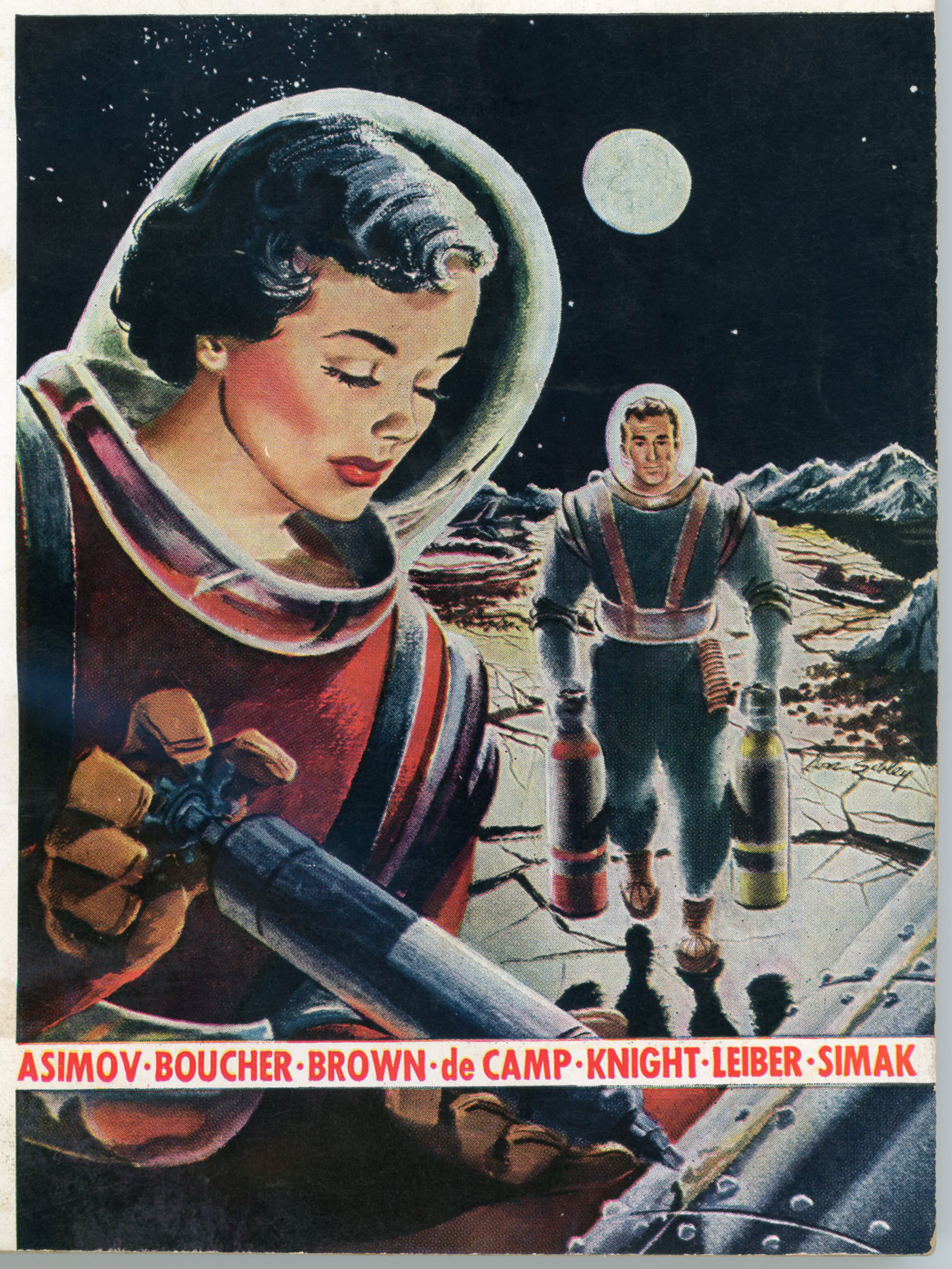

What’s on a book is interesting (hey, that’s why this blog’s here!) but it’s what’s inside that really counts. Some novels; some stories are so compelling that the message they present – whether explicitly or implicitly – demands acknowledgement; demands recognition; demands contemplation. This is so regardless of a tale’s format, physical quality, or (sometimes being generous!) literary venue. In some pulp fiction, there has been profundity. In a few cheap paperbacks, there has been prescience. And even in some works of mainstream fiction, there can be (on infrequent occasion!) meaning. Such as, in the four examples below: Two pulps; a mainstream novel; a cheap paperback. While they certainly merit notice of their cover art, it’s the commonality – expressed in different degrees of sophistication and style – of their understanding of the intersection between human nature, technology, and civilization, and the endurance of civilization, for which they should be recognized.

So, each post features images of the book or pulp’s cover art, followed by a whole, long, big bunch of excerpts.

Astounding Science Fiction – July, 1947 (Featuring “With Folded Hands…”, by Jack Williamson) [William Timmins]

The Temperature of Chaos: Galaxy Science Fiction – February, 1951 (Featuring “The Fireman”, by Ray Bradbury) [Joseph A. Mugnaini; Chesley Bonestell]

The 14th Utopia: Player Piano, by Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. – August, 1952 [Charles Binger]

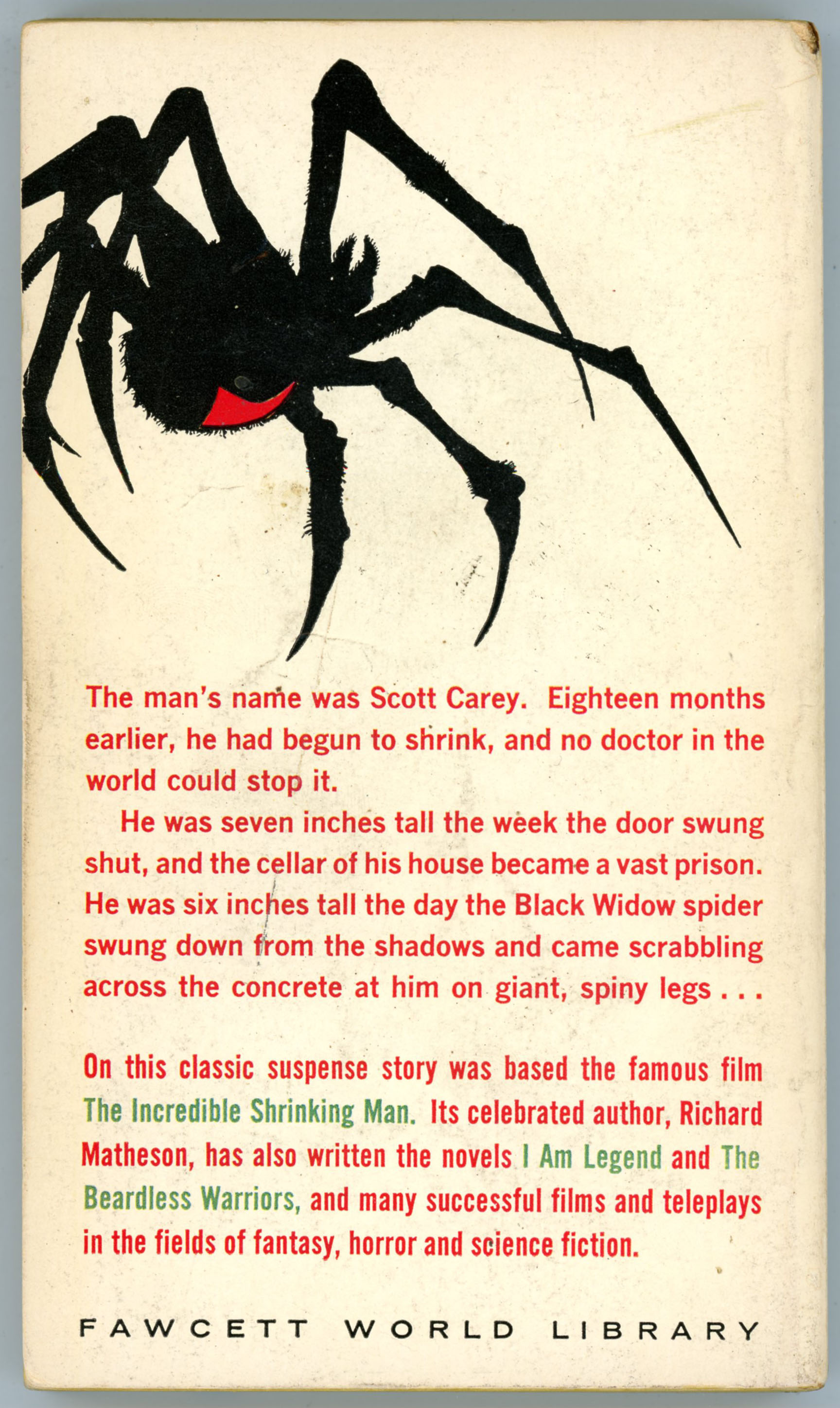

Year of Consent, by Kendell Foster Crossen – 1954 [Richard M. Powers]

______________________________

As for the above, so for the below: Given these four previous posts about the three books in C.S. Lewis’ Space Trilogy…

Out of the Silent Planet – 1956 (1938) [Everett Raymond Kinstler]

Out of the Silent Planet – 1965 (1938) [Everett Bernard Symancyk]

Perelandra – 1957 (1943) [Art Sussman]

Perelandra – 1965 (1943) [Bernard Symancyk]

That Hideous Strength (The Tortured Planet) – 1958 (1945) [Richard M. Powers]

That Hideous Strength – 1965 (1945) [Bernard Symancyk]

… some worthy quotes from That Hideous Strength, the trilogy’s final novel, follow below.

But first…!

here’s George Orwell’s review of the novel from the Manchester Evening News of August 16, 1945, published one day after Emperor Hirohito’s radio broadcast concerning the termination of WW II. A strange and subtle synchronicity, eh? Orwell’s opinion of Lewis’ novel is generally positive, but his criticisms of the magical and supernatural elements in the story are, I think, unwarranted and strangely naive, especially coming from a man of such shining literary skill and moral sensitivity. (I recently finished The Road to Wigan Pier, and, Homage to Catalonia, both of which clearly reveal Orwell’s intellectual honesty, compassion, and political wisdom.) After all, it was Lewis’ specific and deliberate intention – having successively “segued” from Out of the Silent Planet and Perelandra – to combine elements of science-fiction, fantasy, and the supernatural as a warning about the dangers of deification of the human intellect, the seductiveness of power – and especially the desire to feel that one is among a society’s elect, and, an entirely mechanistic view of reality.

Here’s the review…

The Scientist Takes Over

(Reprinted as No. 2720 (first half) in The Complete Works of George Orwell, edited by Peter Davison, Vol. XVII (1998), pp. 250–251)

On the whole, novels are better when there are no miracles in them. Still, it is possible to think of a fairly large number of worth-while books in which ghosts, magic, second-sight, angels, mermaids, and what-not play a part.

Mr. C.S. Lewis’s “That Hideous Strength” can be included in their number – though, curiously enough, it would probably have been a better book if the magical element had been left out. For in essence it is a crime story, and the miraculous happenings, though they grow more frequent towards the end, are not integral to it.

In general outline, and to some extent in atmosphere, it rather resembles G.K. Chesterton’s “The Man Who Was Thursday.”

Mr. Lewis probably owes something to Chesterton as a writer, and certainly shares his horror of modern machine civilisation (the title of the book, by the way, is taken from a poem about the Tower of Babel) and his reliance on the “eternal verities” of the Christian Church, as against scientific materialism or nihilism.

His book describes the struggle of a little group of sane people against a nightmare that nearly conquers the world. A company of mad scientists – or, perhaps, they are not mad, but have merely destroyed in themselves all human feeling, all notion of good and evil – are plotting to conquer Britain, then the whole planet, and then other planets, until they have brought the universe under their control.

All superfluous life is to be wiped out, all natural forces tamed, the common people are to be used as slaves and vivisection subjects by the ruling caste of scientists, who even see their way to conferring immortal life upon themselves. Man, in short, is to storm the heavens and overthrow the gods, or even to become a god himself.

There is nothing outrageously improbable in such a conspiracy. Indeed, at a moment when a single atomic bomb – of a type already pronounced “obsolete” – has just blown probably three hundred thousand people to fragments, it sounds all too topical. Plenty of people in our age do entertain the monstrous dreams of power that Mr. Lewis attributes to his characters, and we are within sight of the time when such dreams will be realisable.

His description of the N.I.C.E. (National Institute of Co-ordinated Experiments), with its world-wide ramifications, its private army, its secret torture chambers, and its inner ring of adepts ruled over by a mysterious personage known as The Head, is as exciting as any detective story.

It would be a very hardened reader who would not experience a thrill on learning that The Head is actually – however, that would be giving the game away.

One could recommend this book unreservedly if Mr. Lewis had succeeded in keeping it all on a single level. Unfortunately, the supernatural keeps breaking in, and it does so in rather confusing, undisciplined ways. The scientists are endeavouring, among other things, to get hold of the body of the ancient Celtic magician Merlin, who has been buried – not dead, but in a trance – for the last 1,500 years, in hopes of learning from him the secrets of pre-Christian magic.

They are frustrated by a character who is only doubtfully a human being, having spent part of his time on another planet where he has been gifted with eternal youth. Then there is a woman with second sight, one or two ghosts, and various superhuman visitors from outer space, some of them with rather tiresome names which derive from earlier books of Mr. Lewis’s. The book ends in a way that is so preposterous that it does not even succeed in being horrible in spite of much bloodshed.

Much is made of the fact that the scientists are actually in touch with evil spirits, although this fact is known only to the inmost circle. Mr. Lewis appears to believe in the existence of such spirits, and of benevolent ones as well. He is entitled to his beliefs, but they weaken his story, not only because they offend the average reader’s sense of probability but because in effect they decide the issue in advance. When one is told that God and the Devil are in conflict one always knows which side is going to win. The whole drama of the struggle against evil lies in the fact that one does not have supernatural aid. However, by the standard of the novels appearing nowadays this is a book worth reading.

This post concludes with a bunch of references to commentary about and discussion of the novel, the most recent of which are N.S. Lyons’ profound “A Prophecy of Evil: Tolkien, Lewis, and Technocratic Nihilism” – also available in podcast form via Audyo – and Rusty Reno’s “That Haunting Nihilism“. (Admittedly, the very title of Lyons’ post inspired the leading word in this post’s title: Technonihilism. One must give credit where credit’s due!)

______________________________

But First, Some Thing to Watch

So, to (try!) to begin on a note of levity, what better way than to poke fun at science scientism than by Thomas Dolby’s “She Blinded Me With Science” (Official Video – HD Remaster – April 15, 2009), at Thomas Dolby Official?

After all, humor may be the refuge of the powerless, but it is a refuge nonetheless.

______________________________

And so, some quotes:

______________________________

The most controversial business before the College Meeting

was the question of selling Bragdon Wood.

The purchaser was the N.I.C.E., the National Institute of Co-ordinated Experiments.

They wanted a site for the building which would house this remarkable organisation.

The N.I.C.E. was the first fruits of that constructive fusion between the state and the laboratory

on which so many thoughtful people base their hopes of a better world. (23)

______________________________

Jewel had been already an old man in the days before the first war

when old men were treated with kindness,

and he had never succeeded in getting used to the modern world. (28)

______________________________

“And what do you think about it, Studdock?” said Feverstone.

“I think,” said Mark, “that James touched on the most important point

when he said that it would have its own legal staff and its own police.

I don’t give a fig for Pragmatometers and sanitation de luxe.

The real thing is that this time we’re going to get science applied to social problems

and backed by the whole force of the state,

just as war has been backed by the whole force of the state in the past.

One hopes, of course, that it’ll find out more than the old free-lance science did;

but what’s certain is that it can do more.” (38)

______________________________

“But it is the main question at the moment:

which side one’s on – obscurantism or Order.

It does really look as if we now had the power to dig ourselves in as a species

for a pretty staggering period, to take control of our own destiny.

If Science is really given a free hand it can now take over the human race

and re-condition it:

make man a really efficient animal. If it doesn’t – well, we’re done.” (40-41)

______________________________

“It’s the real thing at last.

A new type of man; and it’s people like you who’ve got to begin to make him.”

“The practical point is that you and I don’t like being pawns, and we do rather like fighting – especially on the winning side.”

“And what is the first practical step?”

“Yes, that’s the real question.

As I said, the interplanetary problem must be left on the side for the moment.

The second problem is our rivals on this planet.

I don’t mean only insects and bacteria.

There’s far too much life of every kind about, animal and vegetable.

We haven’t really cleared the place yet.

First we couldn’t;

and then we had aesthetic and humanitarian scruples;

and we still haven’t short-circuited the question of the balance of nature.

All that is to be gone into. The third problem is Man himself.”

“Go on. This interests me very much.”

“Man has got to take charge of Man.

That means, remember, that some men have got to take charge of the rest –

which is another reason for cashing in on it as soon as you can.

You and I want to be the people who do the taking charge,

not the ones who are taken charge of. Quite.”

“What sort of things have you in mind?”

“Quite simple and obvious things, at first –

sterilization of the unfit,

liquidation of backward races (we don’t want any dead weights),

selective breeding.

Then real education, including pre-natal education.

By real education I mean one that has no ‘take-it-or-leave-it’ nonsense.

A real education makes the patient what it wants infallibly:

whatever he or his parents try to do about it.

Of course, it’ll be mainly psychological at first.

But we’ll get on to biochemical conditioning in the end and direct manipulation of the brain…”

“But this is stupendous, Feverstone.”

“It’s the real thing at last.

A new type of man; and it’s people like you who’ve got to begin to make him.” (42)

______________________________

“Is there, do you think, anything very seriously wrong with me?”

“There is nothing wrong with you,” said Miss Ironwood.

“You mean it will go away?”

“I have no means of telling. I should say probably not.”

Disappointment shadowed Jane’s face.

“Then – can’t anything be done about it?

They were horrible dreams – horribly vivid, not like dreams at all.”

“I can quite understand that.”

“Is it something that can’t be cured?”

“The reason you cannot be cured is that you are not ill.” (64)

______________________________

“But what is this all about?” said Jane

“I want to lead an ordinary life.

I want to do my own work.

It’s unbearable!

Why should I be selected for this horrible thing?”

“The answer to that is known only to authorities much higher than myself.” (66)

______________________________

“I happen to believe that you can’t study men;

you can only get to know them, which is quite a different thing.

Because you study them,

you want to make the lower orders govern the country and listen to classical music,

which is balderdash.

You also want to take away from them everything which makes life worth living at

not only from them but from everyone except a parcel of prigs and professors.” (71)

______________________________

They walked about that village for two hours

and saw with their own eyes all the abuses and anachronisms they came to destroy.

They saw the recalcitrant and backward labourer and heard his views on the weather.

They met the wastefully supported pauper in the person of an old man

shuffling across the courtyard of the almshouses to fill a kettle,

and the elderly rentier (to make matters worse, she had a fat old dog with her)

in earnest conversation with the postman.

It made Mark feel as he were on a holiday,

for it was only on holidays that he had ever wandered about an English village.

For that reason he felt pleasure in it.

It did not quite escape him that the face of the backward labourer

was rather more interesting than Cosser’s

and his voice a great deal more pleasing to the ear.

The resemblance between the elderly rentier and Aunt Gilly

(When had he last thought of her? Good Lord, that took one back.)

did make him understand how it was possible to like that kind of person.

All this did not in the least influence his sociological convictions.

Even if he had been free from Belbury and wholly unambitious,

it could not have done so,

for his education had had the curious effect

of making things that he read and wrote more real to him than things he saw.

Statistics about agricultural labourers were the substance;

any real ditcher, ploughman, or farmer’s boy, was the shadow.

Though he had never noticed it himself, he had a great reluctance, in his work,

ever to use such words as “man” or “woman,”

He preferred to write about “vocational groups,” “elements,” “classes” and “populations”:

for, in his own way, he believed as firmly as any mystic

in the superior reality of the things that are not seen. (87)

______________________________

“Why you fool, it’s the educated reader who can be gulled.

All our difficulty comes with the others.

When did you meet a workman who believes the papers?

He takes it for granted that they’re all propaganda and skips the leading articles.

He buys his paper for the football results

and the little paragraphs about girls falling out of windows and corpses found in May-fair flats.

He is our problem.

We have to recondition him.

But the educated public, the people who read the highbrow weeklies,

don’t need reconditioning.

They’re all right already.

They’ll believe anything.”

“Don’t you understand anything?

Isn’t it absolutely essential to keep a fierce Left and a fierce Right,

both on their toes and each terrified of the other?

That’s how we get things done.

Any opposition to the N.I.C.E.

is represented as a Left racket in the Right papers and a Right racket in the Left papers.

If it’s properly done, you get each side outbidding the other in support of us —

to refute the enemy slanders.

Of course we’re non-political. The real power always is.”

“I don’t believe you can do that,” said Mark.

“Not with the papers that are read by educated people.”

“That shows you’re still in the nursery, lovey,” said Miss Hardcastle.

“Haven’t you yet realised that it’s the other way round?”

“How do you mean?”

“Why you fool, it’s the educated reader who can be gulled.

All our difficulty comes with the others.

When did you meet a workman who believes the papers?

He takes it for granted that they’re all propaganda and skips the leading articles.

He buys his paper for the football results

and the little paragraphs about girls falling out of windows and corpses found in May-fair flats.

He is our problem.

We have to recondition him.

But the educated public, the people who read the highbrow weeklies,

don’t need reconditioning.

They’re all right already.

They’ll believe anything.”

“As one of the class you mention,” said Mark with a smile, “I just don’t believe it.”

“Good Lord!” said the Fairy, “where are your eyes?

Look at what the weeklies have got away with!

Look at the Weekly Question.

There’s a paper for you.

When Basic English came in simply as the invention of a free-thinking Cambridge don,

nothing was too good for it;

as soon as it was taken up by a Tory Prime Minister it became a menace to the purity of our language. And wasn’t the Monarchy an expensive absurdity for ten years?

And then, when the Duke of Windsor abdicated,

didn’t the Question go all monarchist and legitimist for about a fortnight?

Did they drop a single reader?

Don’t you see that the educated reader can’t stop reading the high-brow weeklies whatever they do? He can’t.

He’s been conditioned.” (99-100)

______________________________

Stone had the look which Mark had often seen before in unpopular boys or new boys at school,

in “outsiders” at Bracton —

the look which was for Mark the symbol of all his worst fears,

for to be one who must wear that look was, in his scale of values, the greatest evil.

His instinct was not to speak to this man Stone.

He knew by experience how dangerous it is to be friends with a sinking man

or even to be seen with him:

you cannot keep him afloat and he may pull you under.

But his own craving for companionship was now acute,

so that against his better judgment he smiled a sickly — smile and said “Hullo!” (109)

______________________________

The least satisfactory member of the circle in Mark’s eyes was Straik.

Straik made no effort to adapt himself to the ribald and realistic tone in which his colleagues spoke.

He never drank nor smoked.

He would sit silent,

nursing a threadbare knee with a lean hand

and turning his large unhappy eyes from one speaker to another,

without attempting to combat them or to join in the joke when they laughed.

Then — perhaps once in the whole evening — something said would start him off:

usually something about the opposition of reactionaries in the outer world

and the measures which the N.I.C.E. would take to deal with it.

At such moments he would burst into loud and prolonged speech,

threatening,

denouncing,

prophesying.

The strange thing was that the others neither interrupted him nor laughed.

There was some deeper unity between this uncouth man and them

which apparently held in check the obvious lack of sympathy,

but what it was Mark did not discover.

Sometimes Straik addressed him in particular,

talking, to Mark’s great discomfort and bewilderment, about resurrection.

“Neither a historical fact nor a fable, young man,” he said, “but a prophecy.

All the miracles — shadows of things to come.

Get rid of false spirituality.

It is all going to happen, here in this world, in the only world there is.

What did the Master tell us?

Heal the sick, cast out devils, raise the dead.

We shall.

The Son of Man — that is, Man himself, full grown — has power to judge the world —

to distribute life without end, and punishment without end.

You shall see. Here and now.”

It was all very unpleasant. (128)

______________________________

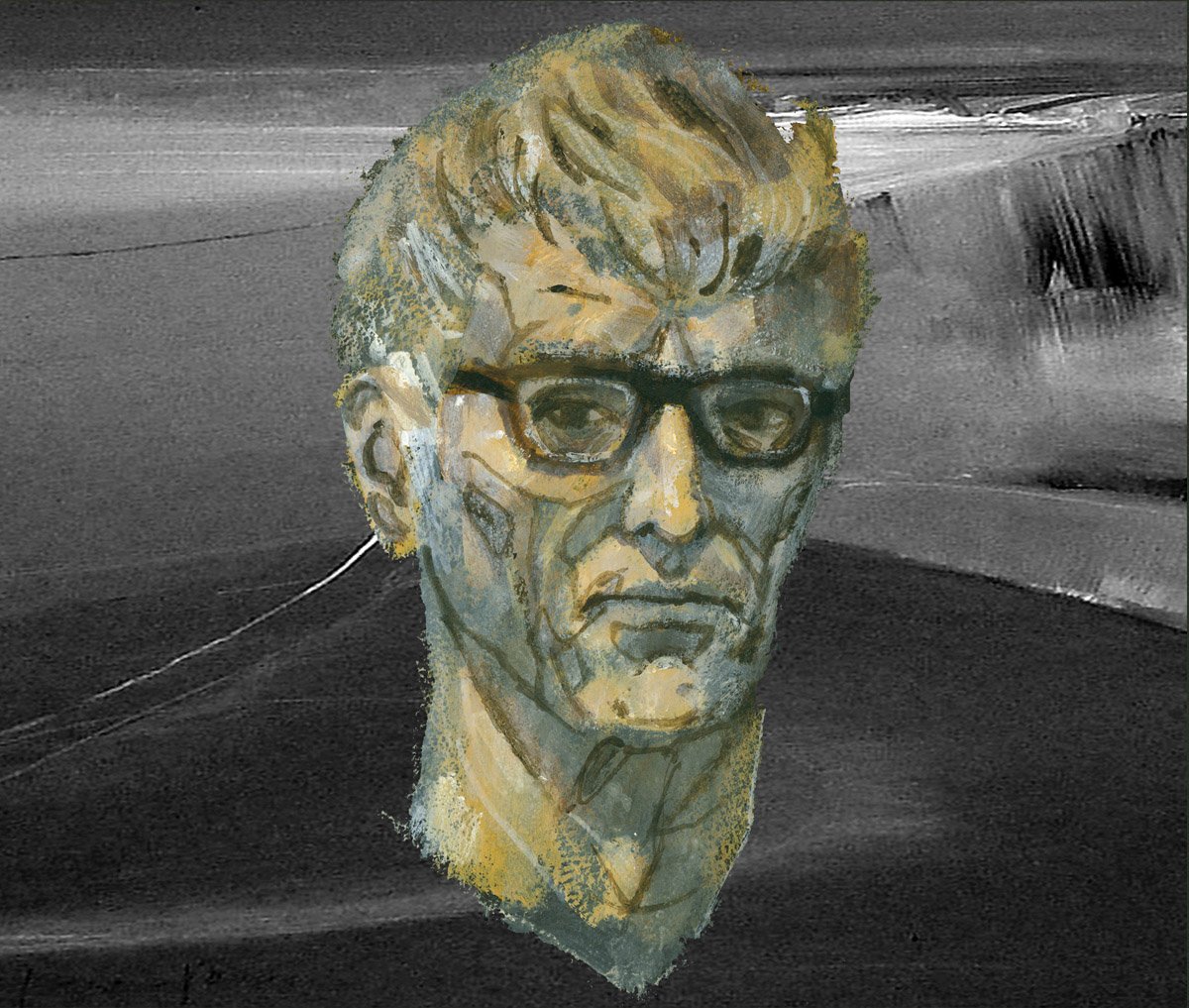

The poster was created by John Paul Cokes and is among several conceptual illustrations for That Hideous Strength that can be viewed at Behance. He’s also created a great series of stylistically similar illustrations for Alfred Bester’s The Stars My Destination, which – like That Hideous Strength; like so many other works of science fiction and fantasy (A.E. van Vogt, anyone?) – have long merited wokeless transfer from the printed page to screen.

______________________________

“It was not his fault,” she said at last.

“I suppose our marriage was just a mistake.”

The Director said nothing.

“What would you — what would the people you are talking of — say about a case like that?”

“I will tell you if you really want to know,” said the Director.

“Please,” said Jane reluctantly.

“They would say,” he answered, “that you do not fail in obedience through lack of love,

but have lost love because you never attempted obedience.”

Something in Jane that would normally have reacted to such a remark with anger or laughter

was banished to a remote distance (where she could still, but only just, hear its voice)

by the fact that the word Obedience —

but certainly not obedience to Mark —

came over her, in that room and in that presence,

like a strange oriental perfume, perilous, seductive, and ambiguous…

“Stop it!” said the Director, sharply.

Jane stared at him, open mouthed.

There were a few moments of silence during which the exotic fragrance faded away.

“You were saying, my dear?” resumed the Director.

“I thought love meant equality,” she said, “and free companionship.”

“Ah, equality!” said the Director.

“We must talk of that some other time.

Yes, we must all be guarded by equal rights from one another’s greed,

because we are fallen.

Just as we must all wear clothes for the same reason.

But the naked body should be there underneath the clothes,

ripening for the day when we shall need them no longer.

Equality is not the deepest thing, you know.”

“I always thought that was just what it was.

I thought it was in their souls that people were equal.”

“You were mistaken,” said he gravely.

“That is the last place where they are equal.

Equality before the law, equality of incomes — that is very well.

Equality guards life; it doesn’t make it.

It is medicine, not food.

You might as well try to warm yourself with a blue-book.”

“But surely in marriage… ?”

“Worse and worse,” said the Director.

“Courtship knows nothing of it; nor does fruition.

What has free companionship to do with that?

Those who are enjoying something, or suffering something together, are companions.

Those who enjoy or suffer one another, are not.

Do you not know how bashful friendship is?

Friends — comrades — do not look at each other. Friendship would be ashamed…”

“I thought,” said Jane and stopped.

“I see,” said the Director.

“It is not your fault.

They never warned you.

No one has ever told you that obedience — humility — is an erotic necessity.

You are putting equality just where it ought not to be.

As to your coming here, that may admit of some doubt.

For the present, I must send you back.

You can come out and see us.

In the meantime, talk to your husband and I will talk to my authorities.” (147-148)

______________________________

No, no; we want geldings and oxen.

There will never be peace and order and discipline so long as there is sex.

When man has thrown it away, then he will become finally governable.

“At present, I allow, we must have forests, for the atmosphere.

Presently we find a chemical substitute.

And then, why any natural trees?

I foresee nothing but the art tree all over the earth.

In fact, we clean the planet.”

“Do you mean,” put in a man called Gould, “that we are to have no vegetation at all?”

“Exactly. You shave your face: even, in the English fashion, you shave him every day.

One day we shave the planet.”

“I wonder what the birds will make of it?”

“I would not have any birds either.

On the art tree I would have the art birds all singing when you press a switch inside the house.

When you are tired of the singing you switch them off.

Consider again the improvement.

No feathers dropped about, no nests, no eggs, no dirt.”

“It sounds,” said Mark, “like abolishing pretty well all organic life.”

“And why not? It is simple hygiene.

Listen, my friends.

If you pick up some rotten thing and find this organic life crawling over it,

do you not say, ‘Oh, the horrid thing. It is alive,’ and then drop it?”

“Go on,” said Winter.

“And you, especially you English, are you not hostile to any organic life except your own

on your own body?

Rather than permit it you have invented the daily bath.”

“That’s true.”

“And what do you call dirty dirt? Is it not precisely the organic?

Minerals are clean dirt.

But the real filth is what comes from organisms —

sweat, spittles, excretions.

Is not your whole idea of purity one huge example?

The impure and the organic are interchangeable conceptions.”

“What are you driving at, Professor?” said Gould.

“After all we are organisms ourselves.”

“I grant it. That is the point. In us organic life has produced Mind.

It has done its work.

After that we want no more of it.

We do not want the world any longer furred over with organic life,

like what you call the blue mould —

all sprouting and budding and breeding and decaying.

We must get rid of it.

By little and little, of course.

Slowly we learn how.

Learn to make our brains live with less and less body:

learn to build our bodies directly with chemicals,

no longer have to stuff them full of dead brutes and weeds.

Learn how to reproduce ourselves without copulation.”

“I don’t think that would be much fun,” said Winter.

“My friend, you have already separated the Fun, as you call it, from fertility.

The Fun itself begins to pass away.

Bah! I know that is not what you think.

But look at your English women. Six out of ten are frigid, are they not? You see?

Nature herself begins to throw away the anachronism.

When she has thrown it away, then real civilisation becomes possible.

You would understand if you were peasants.

Who would try to work with stallions and bulls?

No, no; we want geldings and oxen.

There will never be peace and order and discipline so long as there is sex.

When man has thrown it away, then he will become finally governable.” (172-173)

______________________________

“The world I look forward to is the world of perfect purity.

The clean mind and the clean minerals.

What are the things that most offend the dignity of man?

Birth and breeding and death.

How if we are about to discover that man can live without any of the three?” (174) Filostrato

______________________________

Nature is the ladder we have climbed up by, now we kick her away.

“For the moment, I speak only to inspire you.

I speak that you may know what can be done: what shall be done here.

This Institute — Dio mio, it is for something better than housing and vaccinations

and faster trains and curing the people of cancer.

It is for the conquest of death: or for the conquest of organic life, if you prefer.

They are the same thing.

It is to bring out of that cocoon of organic life which sheltered the babyhood of mind the New Man,

the man who will not die,

the artificial man,

free from Nature.

Nature is the ladder we have climbed up by, now we kick her away.” (177)

______________________________

Here, in this house, you shall meet the first sketch of the real God.

It is a man — or a being made by man —

who will finally ascend the throne of the universe.

And rule forever.

“You are frightened?” said Filostrato.

“You will get over that.

We are offering to make you one of us.

Ahi — if you were outside, if you were mere canaglia you would have reason to be frightened.

It is the beginning of all power.

He lives forever.

The giant time is conquered.

And the giant space — he was already conquered too.

One of our company has already travelled in space.

True; he was betrayed and murdered and his manuscripts are imperfect:

we have not yet been able to reconstruct his space ship.

But that will come.”

“It is the beginning of Man Immortal and Man Ubiquitous,” said Straik.

“Man on the throne of the universe. It is what all the prophecies really meant.”

“At first, of course,” said Filostrato, “the power will be confined to a number —

a small number — of individual men.

Those who are selected for eternal life.”

“And you mean,” said Mark, “it will then be extended to all men?”

“No,” said Filostrato. “I mean it will then be reduced to one man.

You are not a fool, are you, my young friend?

All that talk about the power of Man over Nature —

Man in the abstract —

is only for the canaglia.

You know as well as I do that Man’s power over Nature means the power of some men over other men with Nature as the instrument.

There is no such thing as Man — it is a word.

There are only men.

No! It is not Man who will be omnipotent, it is some one man, some immortal man.

Alcasan, our Head, is the first sketch of it.

The completed product may be someone else.

It may be you. It may be me.”

“A king cometh,” said Straik,

“who shall rule the universe with righteousness and the heavens with judgment.

You thought all that was mythology, no doubt.

You thought because fables had clustered about the phrase, ‘Son of Man,’

that Man would never really have a son who will wield all power. But he will.”

“I don’t understand, I don’t understand,” said Mark.

“But it is very easy,” said Filostrato.

“We have found how to make a dead man live.

He was a wise man even in his natural life.

He lives now forever; he gets wiser.

Later, we make them live better —

for at present, one must concede, this second life is probably not very agreeable to him who has it.

You see?

Later we make it pleasant for some — perhaps not so pleasant for others.

For we can make the dead live whether they wish it or not.

He who shall be finally king of the universe can give this life to whom he pleases.

They cannot refuse the little present.”

“And so,” said Straik, “the lessons you learned at your mother’s knee return.

God will have power to give eternal reward and eternal punishment.”

“God?” said Mark. “How does He come into it? I don’t believe in God.”

“But, my friend,” said Filostrato, “does it follow that because there was no God in the past

that there will be no God also in the future?”

“Don’t you see,” said Straik,

“that we are offering you the unspeakable glory of being present at the creation of God Almighty?

Here, in this house, you shall meet the first sketch of the real God.

It is a man — or a being made by man —

who will finally ascend the throne of the universe.

And rule forever.” (178-179)

______________________________

One of Ransom’s greatest difficulties in disputing with MacPhee

(who consistently professed to disbelieve the very existence of the eldils)

was that MacPhee made the common, but curious assumption that —

if there are creatures wiser and stronger than man

they must be forthwith omniscient and omnipotent.

In vain did Ransom endeavour to explain the truth.

Doubtless, the great beings who now so often came to him

had power sufficient to sweep Belbury from the face of England

and England from the face of the globe;

perhaps, to blot the globe itself out of existence.

But no power of that kind would be used.

Nor had they any direct vision into the minds of men.

It was in a different place, and approaching their knowledge from the other side,

that they had discovered the state of Merlin:

not from inspection of the thing that slept under Bragdon Wood,

but from observing a certain unique configuration in that place

where those things remain that are taken off thine’s mainroad,

behind the invisible hedges, into the unimaginable fields.

Not all the times that are outside the present are therefore past or future.

It was this that kept the Director wakeful, with knitted brow,

in the small cold hours of that morning when the others had left him.

There was no doubt in his mind now that the enemy had bought Bragdon to find Merlin:

and if they found him they would re-awake him.

The old Druid would inevitably cast his lot with the new planners —

what could prevent his doing so?

A junction would be effected between two kinds of power

which between them would determine the fate of our planet.

Doubtless that had been the will of the dark eldils for centuries.

The physical sciences, good and innocent in themselves, had already, even in Ransom’s own time,

begun to be warped, had been subtly manoeuvred in a certain direction.

Despair of objective truth had been increasingly insinuated into the scientists;

indifference to it, and a concentration upon mere power, had been the result.

Babble about the élan vital and flirtations with panpsychism

were bidding fair to restore the Anima Mundi of the magicians.

Dreams of the far future destiny of man

were dragging up from its shallow and unquiet grave the old dream of Man as God.

The very experiences of the dissecting room and the pathological laboratory

were breeding a conviction that

the stilling of all deepset repugnances was the first essential for progress.

And now, all this had reached the stage

at which its dark contrivers thought they could safely begin to bend it back

so that it would meet that other and earlier kind of power.

Indeed they were choosing the first moment at which this could have been done.

You could not have done it with Nineteenth-Century scientists.

Their firm objective materialism would have excluded it from their minds;

and even if they could have been made to believe,

their inherited morality would have kept them from touching dirt.

MacPhee was a survivor from that tradition.

It was different now.

Perhaps few or none of the people at Belbury knew what was happening;

but once it happened, they would be like straw in fire.

What should they find incredible, since they believed no longer in a rational universe?

What should they regard as too obscene,

since they held that all morality

was a mere subjective by-product of the physical and economic situations of men?

______________________________

______________________________

Other Things to Ponder

Some Things to Read

C.S. Lewis on Mere Science, by M.D. Aeschliman, at First Things, October, 1998

A Century in Books – An Anniversary Symposium, by Various Authors, at First Things, March, 2000

George Orwell’s Review of That Hideous Strength by C.S. Lewis, at Amor Mundi (Dale Carrico), February 3, 2009

Lewis vs Haldane, by David Foster, at Chicago Boyz, September 16, 2009

The More You Want, by Tom Gilson, at First Things, February 22, 2012

Ideology, Institutions, and Modern Science, by Joseph Knippenberg, at First Things, December 19, 2012

Book Review: That Hideous Strength, by C S Lewis, by David Foster, at Chicago Boyz, July 24, 2014

Good and Evil in C.S. Lewis’ Space Trilogy, by Dr. Pedro Blas González, at NewEnglishReview, December 2, 2020

Brave New World? 1984? No, CS Lewis’s That Hideous Strength is the Novel That Best Predicted Today’s World, by David Marshall, at Stream.org, September 4, 2021

Medical Mandates: A Hideous Strength, by David Solway, at Pajamas Media, September 12, 2021

“A Prophecy of Evil: Tolkien, Lewis, and Technocratic Nihilism“, by N.S. Lyons, at The Upheaval, November 15, 2022

“The Military-Industrial Complex Doesn’t Run Washington“, by N.S. Lyons, at The Upheaval, January 12, 2023

That Haunting Nihilism, by Rusty R. Reno, at First Things, January, 2023

Some Things to Hear

“A Prophecy of Evil: Tolkien, Lewis, and Technocratic Nihilism (Old Version)”, at TheUpheaval (audyo.ai/theupheaval) (A little fast, but still audible!)

“A Prophecy of Evil: Tolkien, Lewis, and Technocratic Nihilism“, at TheUpheaval (audyo.ai/theupheaval) (As above!)

“The Military-Industrial Complex Doesn’t Run Washington: Something else does“, at TheUpheaval (audyo.ai/theupheaval) (As above doubly!)