While my favorite science fiction illustrators include Richard M. Powers, Virgil W. Finlay, and Hubert Rogers (but there are so many others to chose from!) another mid-twentieth century artist whose works I’ve also featured is Hannes Bok (pseudonym for Wayne F. Woodward), examples of whose art can be viewed at…

… Futuria Fantasia, January, 1940 (Cover illustration)

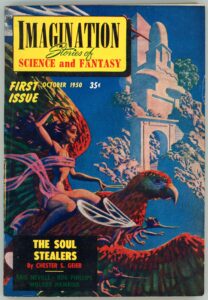

… Imagination, June, 1951 (Cover illustration for “Hell’s Angels”, by Robert Bloch)

… Marvel Science Fiction, November, 1951 (Cover illustration)

… The Explorers (Novel by Cyril M. Kornbluth, August, 1954)

… The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, November, 1963 (Cover illustration for “A Rose for Ecclesiastes”, by Roger Zelazny)

His extraordinarily prolific output (accessible here) includes many (many!) magazine covers, such as this first issue of Science Stories, which was published between 1953 and 1955.

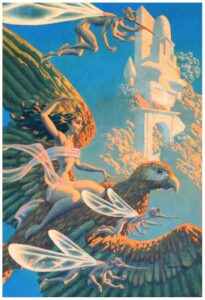

Here’s an image of the magazine’s cover illustration as Bok originally created. It’s featured at FineArt.HA.com, where it’s described (well, this was in 2012, 12 years ago as of this year of 2024!) as being part of the collection of “First Fan, Jack Cordes”, having been acquired from Bok himself. The composition is “mixed media on board”; dimensions 16.25 x 11 inches. While details are virtually identical to those as reproduced in the actual magazine cover, the differences in color saturation are obvious. Perhaps this is because this original painting has faded over the years since 1953. Equally – perhaps – the colors of the inks used in the magazine’s publication simply weren’t identical to those in Bok’s original composition. Or – ? – the delicacy of the colors in Bok’s painting couldn’t be replicated by printing in quantity, which could only generate images of deeper saturation and greater contrast.

But, more importantly, the image is emblematic of Bok’s very style, which – by his use of glazing – is immediately recognizable by virtue of its sense of three-dimensionality and texture, as emblematic in its own way as the distinctiveness of the works of Virgil Finlay or Edmund Emshwiller. The Wikipedia entry for Bok uses the word “luminous” to characterize his work, an apt description.

Bok’s mentor was Maxfield Parrish, whose work “Stars” (1926) appears below. Though Parrish undoubtedly influenced Bok, the subject matter and eventual style of these artists’ works was obviously utterly different, with much of Bok’s work – like that of Hubert Rogers, Paul Orban, and Virgil Finlay – having a mythic or symbolic “feel” to it. For example, the astronauts, adventurers, damsels, and women in his compositions appear in stylized, simplified, often idealized form, lacking the technical intricacy and imagineered equipment typical of those subjects in works by Edmund Emshwiller (EMSH). The same for his aliens, creatures, monsters, and robots, of which there are plenty.

Illustration for “Hocus Pocus Universe“, by Jack Williamson (page 7)

____________________

In searching for newspaper articles about Bok, I found this solitary item via FultonHistory, from 1945:

Various Ventures in Art

Concerning Exhibitions in Half a Dozen of the Galleries

The Sun (New York)

Saturday, January 6, 1945

Hannes Bok, a young artist out of the West, is having what seems to be his first one-man show at the Ferargil Gallery, 63 East 57th Street. The artist inclines definitely to the imaginative in his subject matter, at least, but does not seem able to present his themes effectively. His design is rather heavy, his color, as a rule, rather hot and uninteresting. Among his more attractive canvases are “Night Ride and Sunrise,” “I Saw Three Ships,” “Seascape,” “Water World,” and “Chinese Landscape.”

____________________

Bok died in 1964 and is buried in Westchester County, New York. (His biographical profile at FindAGrave has only the most nominal of information about him.) In 1965, Martin Jukovsky penned this tribute to Hannes Bok – appropriately and simply titled “Bok” – which was published in Castle of Frankenstein magazine (Volume 2, Number 2).

BOK

On April 11, 1964, Hannes Bok died of a heart attack. I considered myself a very close friend, yet after the initial shock of the news, I found to my surprise I could feel no grief. I could only consider the unstoppable perpetual motion Bok – the Hannes Bok that would always be at work on something: a painting, a mask, a novel, an astrological chart, letters to his crowd of friends and clients. You would watch him in motion, you would then watch him sitting still – he would still be in motion! This man – an epitome of the creative individual – anyone who knew him could hardly believe that the momentum of his wakefulness and vitality would not carry him past any slight obstacle such as death.

To pay an ordinary visit to Bok I would try to notify him a bit in advance of my coming. Bok never owned a phone and appreciated knowing approximately when his doorbell might ring, as he might be in the middle of a long steady brushstroke and the sudden sound might make his hand leap. After climbing a healthy five flights to his apartment and trying the bell, a round and happy white-haired man would open the door and let me in. The front room and the foyer were the whole of his living space. The walls were given to gravity-defying towers of orange crates, all painted by hand in colorful patterns, containing books and records. In the spaces between were mostly paintings by Bok and several by Jack Gaughan and Maxfield Parrish. Throughout his life, Bok doted on Parrish; he had carried on a correspondence and friendship since childhood with that great American illustrator. Parrish’s influence is obvious in Bok’s art, though the methods are used to much different ends.

Hanging with the paintings were a few odd-looking masks. Some bad grotesque proboscises and goggling eyes, others had gnomelike faces, others had the noble high-cheekboned features and triangular faces of the familiar Bok hero and heroine. These were the paper strip masks he was working on; they were Bok illustrations in the round – Bok’s own brand of sculpture.

Dominating all this was the desk, behind which would sit Hannes Bok.

While talking, he would continually reach into the drawers and bring out something to illustrate or add to his point. A toy, a dinosaur replica, a ledger with some ancient note written so small as to be just within the limits of human eyesight. He made his own sound effects; if he were to drop something on the floor he would exclaim “CLUNK!” Upon the desk were his astrological files containing the names, birthdates, and astrological analyses of friends, clients, famous people, and people of interesting types. The first two groups were confidential, for Bok had the integrity of a priest or psychoanalyst.

I have dwelt on his room so, only because like so many unique and creative people his room was a true projection of himself. To be in Bok’s room was to be in Bok’s brain. And this hermitage, like Bok, was a wonderful cell of bright colors and spontaneous peak action.

I spent much time talking with Hannes Bok about movies. His taste ran to the spectacular, the fantastic, the colorful. On his list, the great film was KING KONG. To Bok though, KONG was more than a great film, it was what he called a “traumatic film.” A “traumatic film” was one which children talked about for years afterward, perhaps – as with Bok – for the rest of their lives. Such a film would impress a child as a great event and could shape his tastes from then on. (JASON AND THE ARGONAUTS was the latest example Bok named of this kind of film.) Bok’s first viewing of KING KONG was certainly a childhood trauma-equal to his discovery of Parrish at about the same time. Before KING KONG he had never heard any music of a serious nature; his parents had disapproved of music and forbidden his playing any on the radio. KONG’s dramatic score by Max Steiner impressed him so that he sought out as much as could find of similar music. The search soon led him to the classics, but Bok never forgot Steiner. When Bok’s television was working, he would try to catch any film with a Steiner score on the late movies. He eventually visited him in Hollywood and then carried on a lengthy correspondence. His collection of Steiner recordings is practically complete-down to a transcription of the KONG score given him by Steiner on his visit.

By his own count, Bok had seen KING KONG at least fifty times. The most unusual showing he had been to was about twenty years ago in a Seattle skid-row movie house. He sat down to see the exalted film and – Wham-Bam! To his surprise, the film was over in about twenty minutes. To squeeze as many showing as possible into each day, the flea-trap theatre was showing just the first and last reels. Nonetheless, Bok enjoyed it immensely, for, after all, it was KONG.

Like most people who are at all interesting, he never gave up childish things. To his last day he preserved an awe of the things about him, an obsession with the world of the senses. Fortunately for all, he had an easy time of translating his peculiar vision into visible form.

So for last, I’ll end this memoir as Bok typically ended a letter:

“with which I sign off

with skranjified bilpscrippens”

MARTIN JUKOVSKY

Jukovsky’s essay features a single illustration by Bok, symbolizing Yin and Yang. Here it is:

More Stuff to Read…

Hannes Bok, at…

… Wikipedia

… FindAGrave

… Zinewiki

… Internet Speculative Fiction Database

… American Art Archives

Comic Art Fans (Superb examples of his work! – at least, as of August, 2022)

… Grapefruit Moon Gallery

… The Fanac Fan History Project (“The Hannes Bok Illustration Index”)

… Heritage Auctions (Again, wonderful examples of his work, including paper mache! – as of August, 2022)

… Hollywood Metal

… The Korshak Collection

… Pulp Artists

… ShrineODreams

… Zenith City Press

Maxfield Parrish, at…

… Wikipedia

… ArtNet

… American Illustration

… Illustration History

… ARC (Art Renewal Center)

Jack Williamson, at…

… Wikipedia

… GoodReads

… Internet Speculative Fiction Database

Other Worlds, at…

… Luminist Archive (Cover illustrations, and downloadable PDFs)

Other Worlds, Universe Science Fiction, and Science Stories, at…

… Wikipedia

Science Stories, at…

… Internet Speculative Fiction Database

… VISCO: The Visual Index of Science Fiction Cover Art