Tom Godwin’s short story “The Gulf Between” was a cautionary tale about using computer technology to supplant human decision-making, set within the overlapping contexts of the creation of the ultimate (robotic) soldier, and, mans’ first venture into space. Godwin’s “The Cold Equations” is different: The story is a stunning exploration of the classical philosophical dilemma of balancing the life of one, versus the life of many, set within the frontier of a future space-faring civilization.

Tom Godwin’s short story “The Gulf Between” was a cautionary tale about using computer technology to supplant human decision-making, set within the overlapping contexts of the creation of the ultimate (robotic) soldier, and, mans’ first venture into space. Godwin’s “The Cold Equations” is different: The story is a stunning exploration of the classical philosophical dilemma of balancing the life of one, versus the life of many, set within the frontier of a future space-faring civilization.

Though the latter tale is far better known within and even beyond the genre of science-fiction, the cord linking the two stories being Godwin’s adept use of an imagined future as the setting for confronting and resolving – in a deeply unsettling, unflinching manner – questions of man’s uniqueness, and, the inherent spiritual value of the individual. Though the stories are (unsurprisingly) somewhat dated on technological grounds – well, they were written over a half-century ago – overall, the writing is tight, crisp, and direct, their length belying their impact and the import of their underlying themes.

“The Cold Equations” has been adapted for radio, television, and web formats, testimony to the tale’s power and literary merit. Similarly, the story has been anthologized many times, one example being in volume one of the Science Fiction Hall of Fame, published in November of 1972.

The story, scripted by George Lefferts and with the roles of pilot Barton and passenger Marilyn voiced by Court Benson and Jill Meredith, was broadcast as episode 15 of the X Minus One radio program on August 8, 1955. The play can also be downloaded from Archive.org.

The two television versions of the story comprise the Twilight Zone production of January 7, 1989 (available on YouTube), and the FilmRise / Alliance Atlantis movie of December 7, 1996, the latter receiving widely varying reviews at both IMDB and Amazon.

Oddly, the several YouTube versions of the Twilight Zone version manifest the same strange problem: About one hour long, all are comprised of three copies of the episode “spliced” together, whereas the actual episode – without commercial breaks – is only 21 minutes long.

Though appearing under a different title – “Stowaway” – the DUST YouTube channel’s version of The Cold Equations, released on April 7, 2018, is a superb rendering of Godwin’s story, the brevity (12 minutes) and pacing of the film closely paralleling the feel of the original story. The acting is excellent (the CG, too), but (?!) the names of the actor and actress are not presented.

______________________________

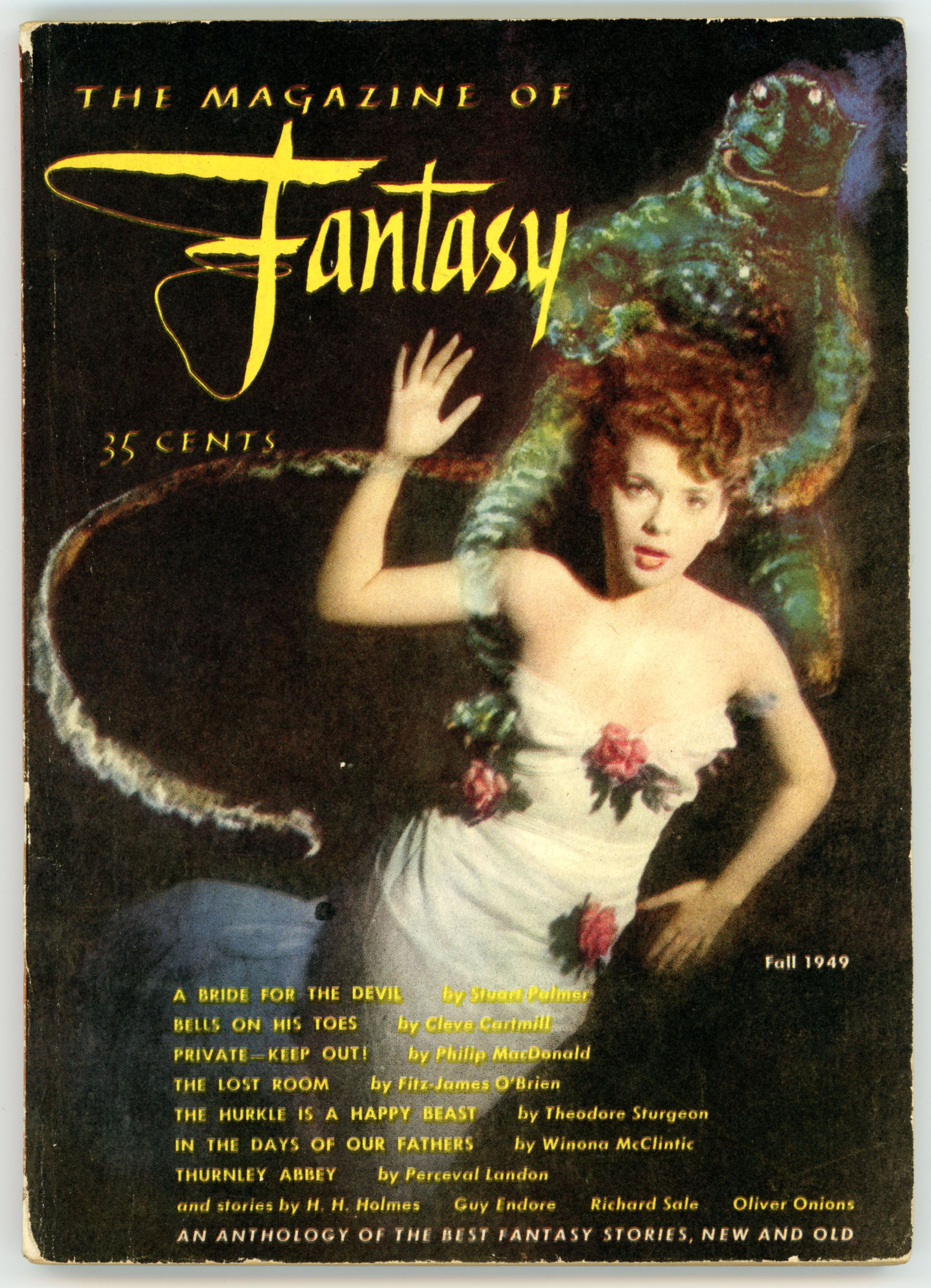

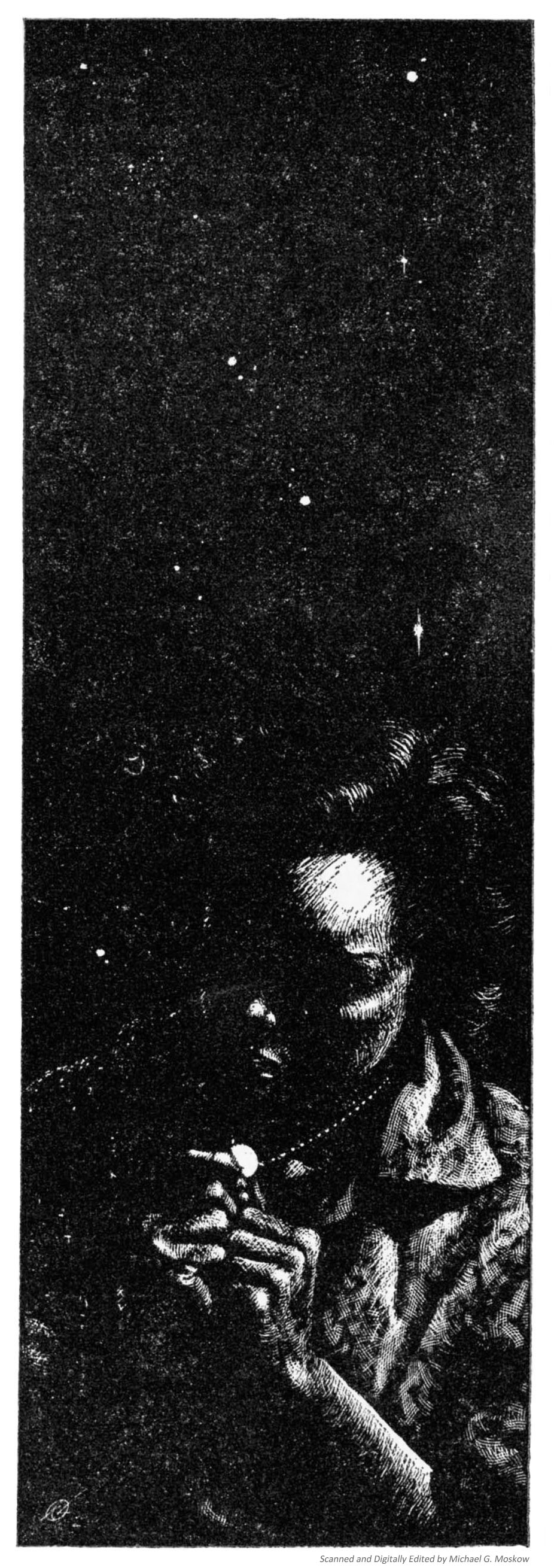

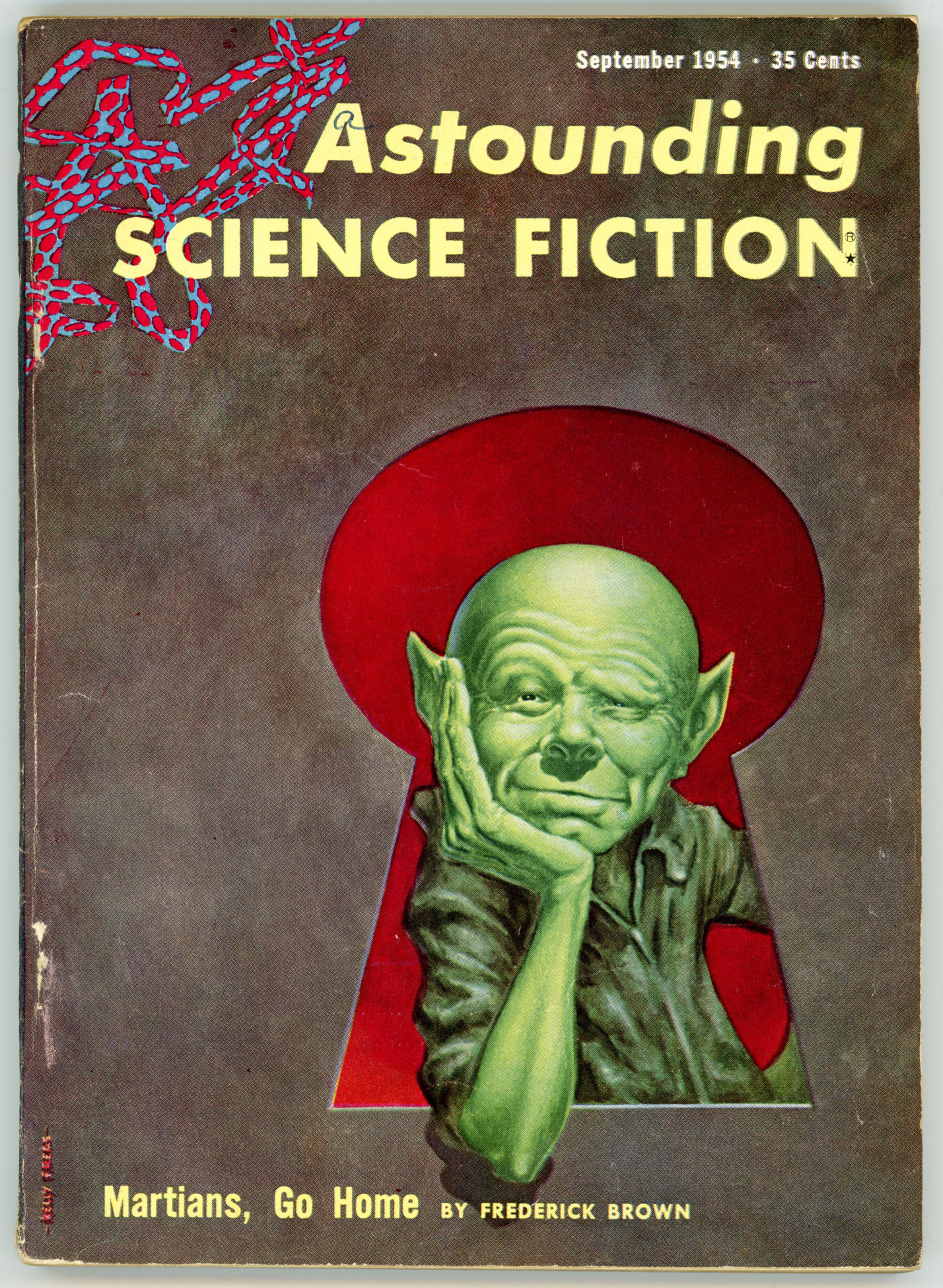

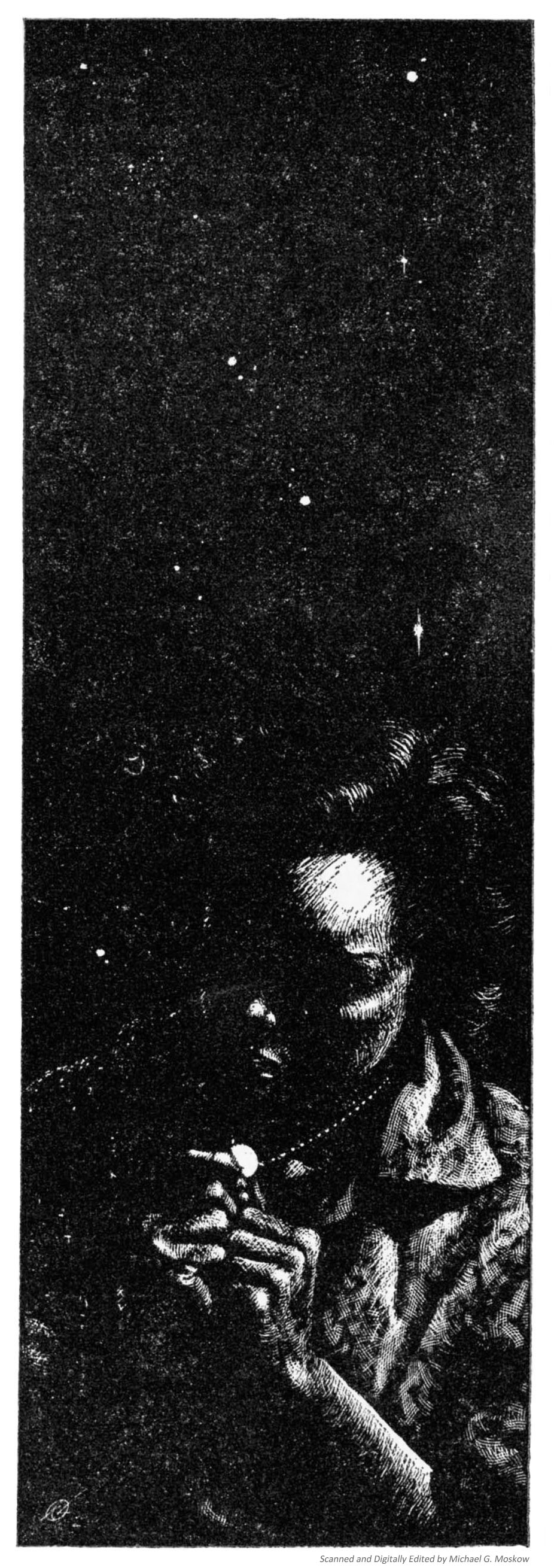

Though Frank Kelly Freas’ illustrations and cover art were often whimsical, humorous, and – at least in his early years – highly creative (the cover is superb!), such qualities would not have befitted art accompanying “The Cold Equations”. Thus, the images of Barton and Marilyn are aptly subdued and pensive, while the leading image – a simple depiction of a spacecraft which seems to have jettisoned an unidentified “something” as it approaches a planet in crescent phase – symbolizes the central aspect of the story. These appear below, accompanied by key passages from the story, which is available in full text at LightSpeedMagazine.

______________________________

He began to check the instrument readings,

going over them with unnecessary slowness.

She would have to accept the circumstances

and there was nothing he could do to help her into acceptance;

words of sympathy would only delay it.

It was 18:20 when she stirred from her motionlessness and spoke.

“So that’s the way it has to be with me?”

He swung around to face her.

“You understand now, don’t you?

No one would ever let it be like this if it could be changed.”

“I understand”, she said.

Some of the color had returned to her face

and the lipstick no longer stood out so vividly red.

“There isn’t enough fuel for me to stay;

when I hid on this ship I got into something I didn’t know anything about

and now I have to pay for it.”

She had violated a man-made law that said KEEP OUT

She had violated a man-made law that said KEEP OUT

but the penalty was not of man’s making or desire

and it was a penalty men could not revoke.

A physical law had decreed:

h amount of fuel will power an EDS with a mass of m safely to its destination;

and a second physical lad had been decreed:

h amount of fuel will not power an EDS with a mass of m plus x safely to its destination.

EDSs obeyed only physical laws

and no amount of human sympathy for her could alter the second law.

“But I’m afraid.

I don’t want to die – not now.

I want to live and nobody is doing anything to help me

everybody is letting me go ahead and acting just like nothing was going to happen to me.

I’m going to die and nobody cares.”

“We all do,” he said.

“I do and the commander does and the clerk in Ship’s Records;

we all care and each of us did what little he could to help you.

It wasn’t enough – it was almost nothing – but it was all we could do.”

“Not enough fuel – I can understand that,” she said,

as though she had not heard his own words.

“But to have to die for it.

Me, alone –

How hard it must be for her to accept the fact.

How hard it must be for her to accept the fact.

She had never known danger of death;

had never known the environments where the lives of men could be as fragile

as sea foam tossed against a rocky shore.

She belonged on gentle Earth,

in that secure and peaceful society where she could be young and gay and laughing

with the others of her kind;

where life was precious and well-guarded

and there was always the assurance that tomorrow would come.

She belonged in that world of soft winds and warm suns,

music and moonlight and gracious manners

and not on the hard, bleak frontier.

— Tom Godwin —

— 1954 —

This anthology would be reprinted in 1970 under Ace Books Catalog Number 91354, with cover art by Jack Gaughan.

This anthology would be reprinted in 1970 under Ace Books Catalog Number 91354, with cover art by Jack Gaughan.