And since he had lasted –

survived –

with a sick headache –

he would not quibble over words –

was there an assignment implicit?

Was he meant to do something?

______________________________

______________________________

“During the war I had no belief, and I had always disliked the ways of the Orthodox.

“During the war I had no belief, and I had always disliked the ways of the Orthodox.

I saw that God was not impressed by death.

Hell was his indifference.

But inability to explain is no ground for disbelief.

Not as long as the sense of God persists.

I could wish that it did not persist.

The contradictions are so painful.

No concern for justice?

Nothing of pity?

Is God only the gossip of the living?

Then we watch these living speed like birds over the surface of a water,

and one will dive or plunge but not come up again and never be seen any more.

And in our turn we will never be seen again,

once gone through that surface.

But then we have no proof that there is no depth under the surface.

We cannot even say that our knowledge of death is shallow.

There is no knowledge.

There is longing, suffering, mourning.

These come from need, affection, and love –

the needs of the living creature, because it is a living creature.

There is also strangeness, implicit.

There is also adumbration.

Other states are sensed.

All is not flatly knowable.

There would never have been any inquiry without this adumbration,

there would never have been any knowledge without it.

But I am not life’s examiner, or a connoisseur, and I have nothing to argue.

Surely a man would console, if he could.

But that is not an aim of mine.

Consolers cannot always be truthful.

But very often, and almost daily, I have strong impressions of eternity.

This may be due to my strange experiences, or to old age.

I will say that to me this does not feel elderly.

Nor would I mind if there were nothing after death.

If it is only to be as it was before birth, why should one care?

There one would receive no further information.

One’s ape restiveness would stop.

I think I would miss mainly my God adumbrations in the many daily forms.

Yes, that is what I should miss.

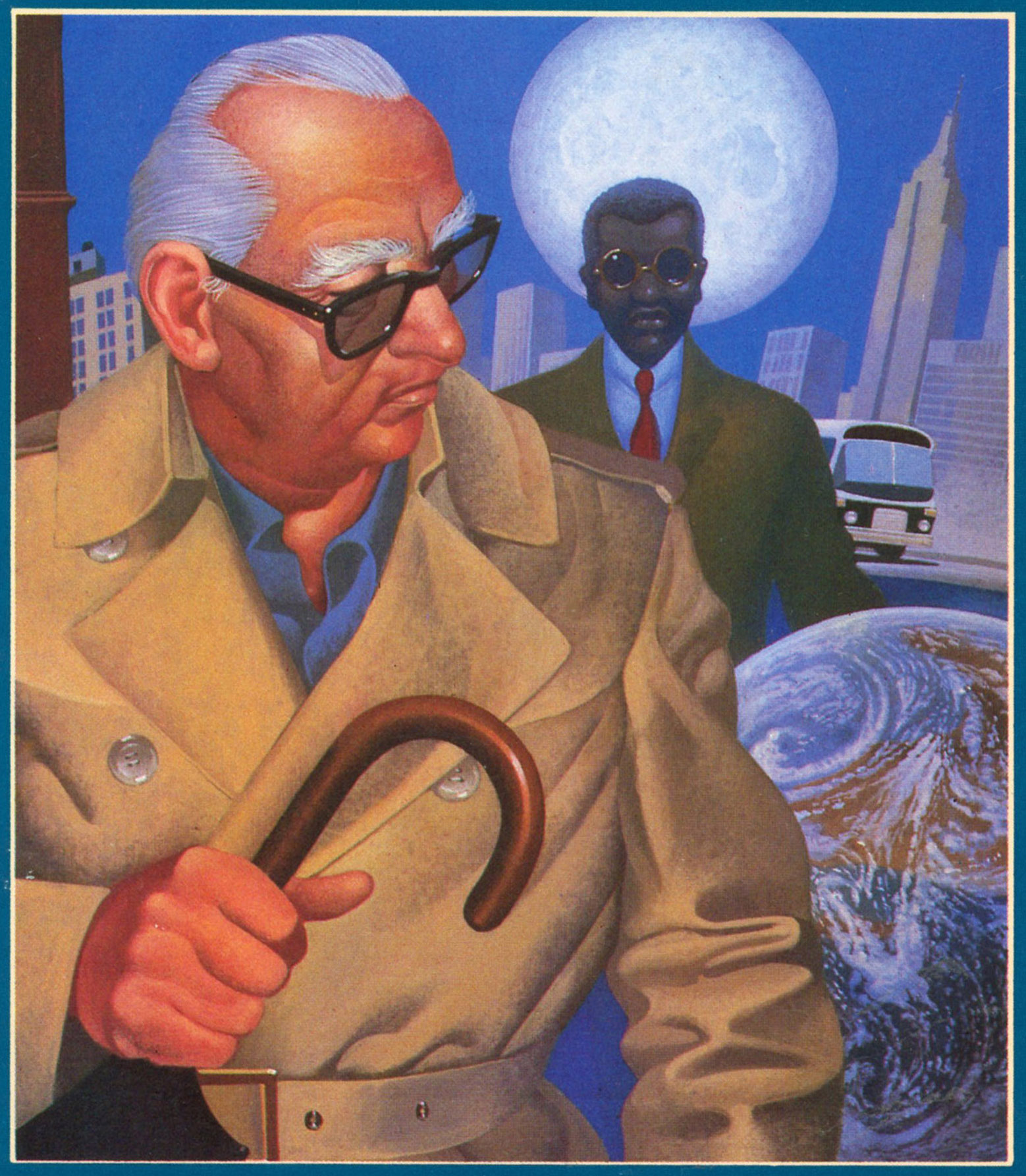

So then, Dr. Lai, if the moon were advantageous for us metaphysically, I would be completely for it.

As an engineering project, colonizing outer space,

except for the curiosity, the ingenuity of the thing,

is of little real interest to me.

Of course the drive, the will to organize this scientific expedition must be one of those irrational necessities that make up life –

this life we think we can understand.

So I suppose we must jump off, because it is our human fate to do so.

If it were a rational matter, then it would be rational to have justice on this planet first.

Then, when we had an earth of saints, and our hearts were set upon the moon,

we could get in our machines and rise up …”

(236-237)

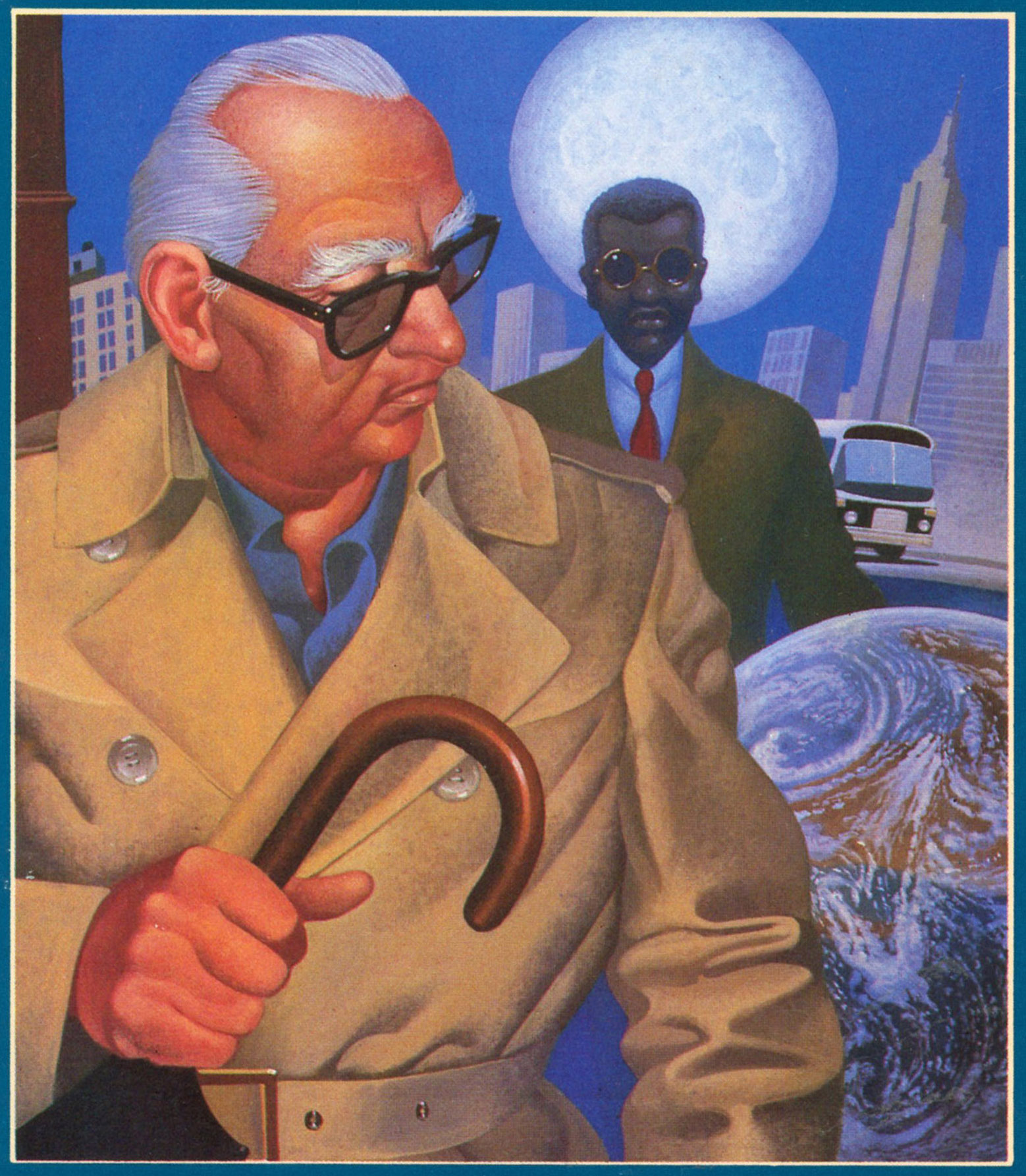

Margotte had much to say.

She did not notice his silence.

By coming back, by preoccupation with the subject,

the dying, the mystery of dying, the state of death.

Also, by having been inside death.

By having been given the shovel and told to dig.

By digging beside his digging wife.

When she faltered he tried to help her.

By this digging, not speaking, he tried to convey something to her and fortify her.

But as it had turned out, he had prepared her for death without sharing it.

She was killed, not he.

She had passed the course, and he had not.

The hole deepened, the sand clay and stones of Poland, their birthplace, opened up.

He had just been blinded, he had a stunned face,

and he was unaware that blood was coming from him

till they stripped and he saw it on his clothes.

When they were as naked as children from the womb,

and the hole was supposedly deep enough, the guns began to blast,

and then came a different sound of soil.

The thick fall of soil.

A ton, two tons, thrown in.

A sound of shovel-metal, gritting.

Strangely exceptional, Mr. Sammler had come through the top of this.

It seldom occurred to him to consider it an achievement.

Where was the achievement? He had clawed his way out.

If he had been at the bottom, he would have suffocated.

If there had been another foot of dirt.

Perhaps others had been buried alive in that ditch.

There was no special merit, there was no wizardry.

There was only suffocation escaped.

And had the war lasted a few months more, he would have died like the rest.

Not a Jew would have avoided death.

As it was, he still had his consciousness, earthliness, human actuality –

got up, breathed his earth gases in and out, drank his coffee,

consumed his share of goods, ate his roll from Zabar’s, put on certain airs –

all human beings put on certain airs – took the bus to Forty-second Street

as if he had an occupation, ran into a black pickpocket.

In short, a living man.

Or one who had been sent back again to the end of the line.

Waiting for something.

Assigned to figure out certain things, to condense, in short views,

some essence of experience, and because of this having a certain wizardry ascribed to him.

There was, in fact, unfinished business.

But how did business finish?

We entered in the middle of the thing and somehow became convinced that we must conclude it.

How?

– Saul Bellow –

______________________________

______________________________