Prose and poetry have similarities…

Both use language to convey information; both can relate a story or present a tale; both are suitable for describing realms of fact or fiction; both can engender within the reader a new perspective of the “world”, whether that be the physical world or the reader’s “interior” world. And, both can affect the soul.

Poetry and prose have differences…

The animating and central power of poetry arises from either its ambiguity or its structure, and often both; from the very language used in poetic works, which at its deepest level subordinates pure description to analogy, simile, metaphor, and symbolism; from the way in which poetry affects those facets of the human psyche for which words are either inadequate or irrelevant: the “worlds” of emotion, intuition, and symbolism.

And so, having begun this blog in 2016 (it’s April in the year 2024 – Nisan 5784 in the Hebrew calendar – as this is written) given that the overwhelming majority of my posts thus far pertain to art and illustration in the world of prose – both fiction and non-fiction – it’s now time to venture (allegorically speaking, of course!) to the world of poetry. And specifically, to the oeuvre of Uri Tzvi Greenberg (or, Uri Tsevi Grinberg; unless quoting other sources, hereafter in this and related posts “Greenberg“) a modernist poet whose works, in Yiddish and Hebrew, were published from 1916 through at least September of 1973 (I’m unsure of the date of his “last” work of poetry).

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

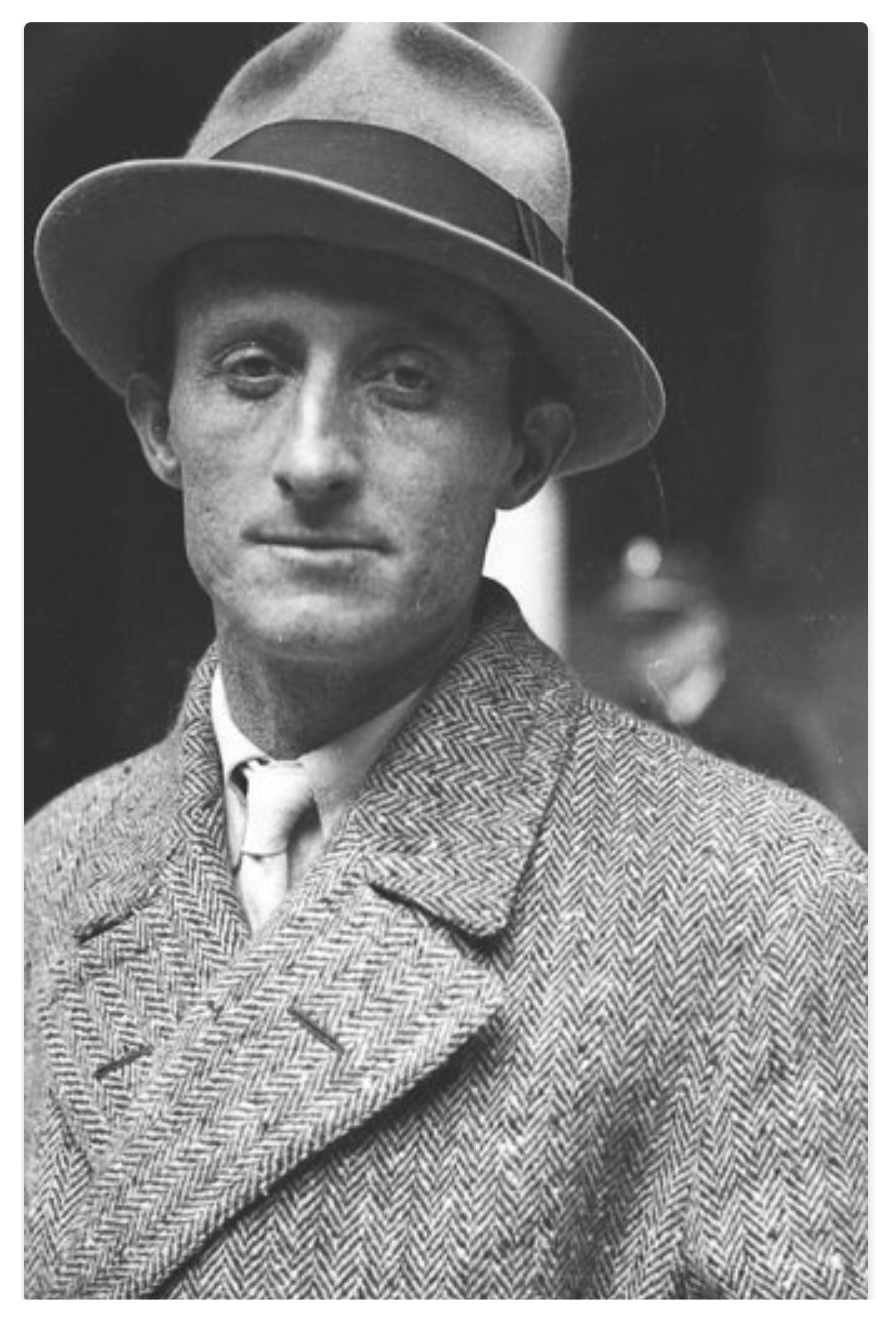

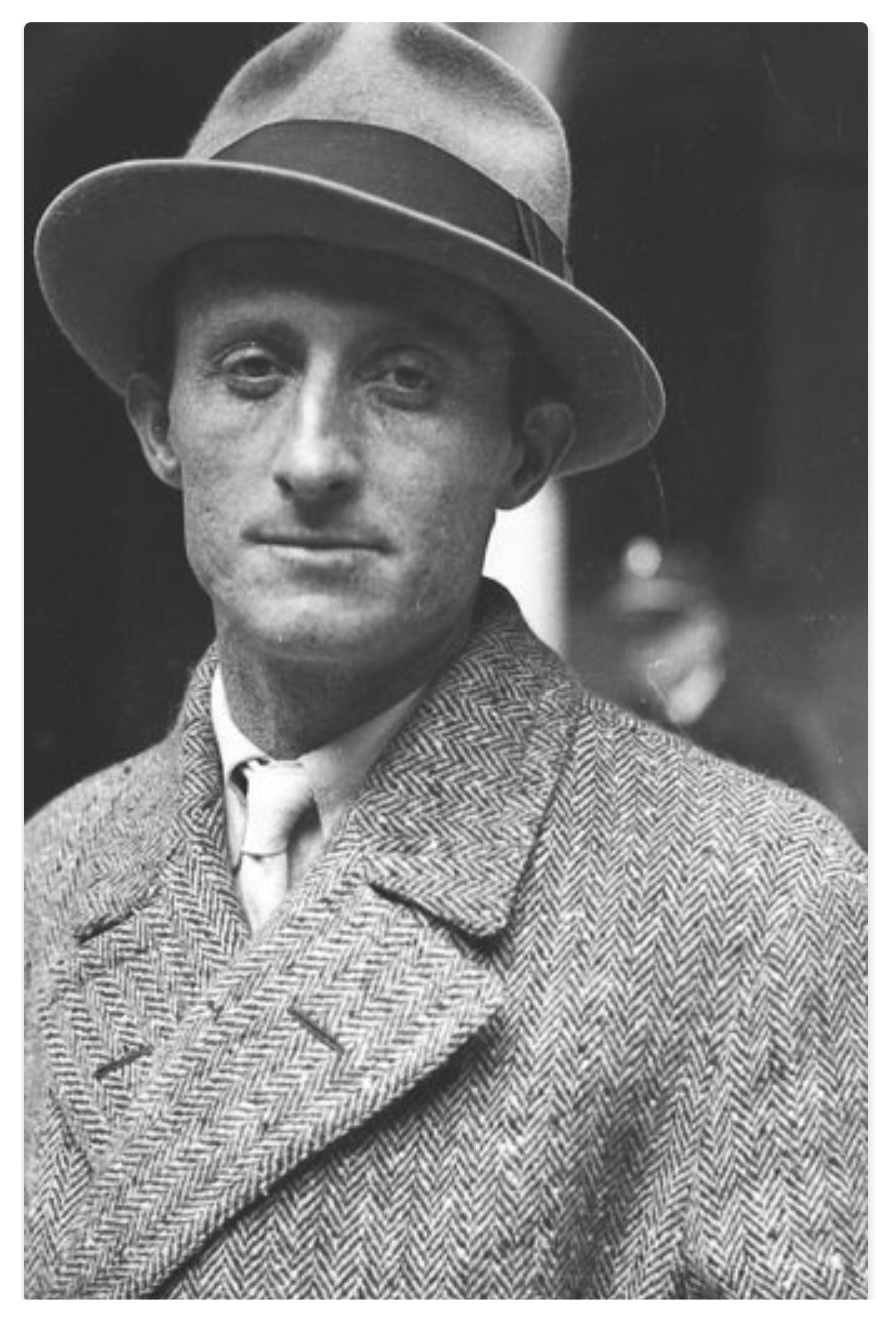

Uri Zvi Greenberg, 1932 (From Zeev Galili’s blog, Logic in Madness (היגיון בשיגעון))

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

From YIVO: “Uri Tsevi Grinberg (or Greenberg) was a trailblazer of radical modernism in both Hebrew and Yiddish literatures, one of the leaders of the Revisionist Zionist movement (from 1930), and a member of the first Israeli Knesset.”

Born into a prominent Hasidic town in Galicia, Austria-Hungary on September 22, 1896, and raised in Lemberg (Lwow), he served as an infantryman in the armed forces of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire during the “Great War”, and though unwounded, the horror and impact of that experience would be a significant influence upon his later compositions. Returning after his military service to the town where he was raised, he moved to Warsaw in 1920, where he resided until forced to leave for Berlin in 1923. The impetus for his departure was the reaction of Polish authorities to views about Jesus expressed in the poem “Royte epl fun veybeymer” (“Red Apples from the Trees of Pain”)). He emigrated to the Yishuv (pre-1948 Israel) in the latter half of 1923. Initially associated with the Labor Zionist Movement and writing for the newspaper Davar, by 1930 he joined the Revisionist Camp, and later, after Israel’s re-establishment in 1948, joined Menachem Begin’s Herut Movement. As stated at Wikipedia, “Widely regarded among the greatest poets in the country’s history, he was awarded the Israel Prize in 1957 and the Bialik Prize in 1947, 1954 and 1977, all for his contributions to fine literature. Greenberg is considered the most significant representative of modernist Expressionism in Hebrew and Yiddish literature.”

The many themes reflected in his poems – well, going by my overview of those works available to me in English! – include (not in any chronological order) the experience, horror, and impact of war upon men (here, Uri Greenberg means all men) and questions of theodicy that inevitably arise from this; one’s intellectual and psychological relationship with the past – the Jewish past – engendered by living within the land of Eretz Israel; the threat and reality of anti-Jewish violence in Eastern Europe, and, the implications of this for the survival of the Jews in those lands; a desire to symbolically reclaim and reconnect Jesus – a simple man; a person – to the Jewish people as a fully mortal human being and distinct individual rather than a man-god, unencumbered from millennia of accumulated non-Jewish religious and cultural mythology; in his latter poems (which seem to be marked by a sense of foreboding, if not gloom), the imperative of maintaining a sense of Jewish pride and solidarity contraposed against (as warned by Nathan Alterman) a “shadow of dullness”: a mysterious and enervating loss of identity and purpose. And (yes, of course) much more.

He died on May 8, 1981, and is buried at the Mount of Olives Cemetery, in Jerusalem, Israel; the precise location of his grave being shown here.

I knew absolutely nothing about Uri Greenberg – didn’t even know the man’s name! – until almost exactly nine years ago, when I discovered him by way of Professor Michael Weingrad’s English-language translation of Greenberg’s poem “In the Crucifix Kingdom” (Yiddish “In malkhus fun tseylem“; alternate titles “By the Kingdom of the Cross” and “In the Kingdom of the Cross”) at Mosaic Magazine. Fortunately still accessible in its entirety, Professor Weingrad’s piece is entitled, “An Unknown Yiddish Masterpiece That Anticipated the Holocaust – Written in 1923, “In the Crucifix Kingdom” depicts Europe as a Jewish wasteland. Why has no one read it?“, and comprises five sections.

First, a brief yet substantive biography of Greenberg in terms of the events that steered the course of his life.

Second, the way in which Greenberg’s clear perception (I believe as valid in 2024 as it was in 1923) of the historical experience of the Jewish people in Europe, within a civilization undergirded by the (only superficially opposed!) foundations of Christianity, and, Enlightenment Liberalism, was the animating force behind his poem, which itself is an,”…indictment of Christian Europe [that] is searing and relentless.”

Third, the poem’s historical significance in terms of both 20th Century Yiddish Literature and modernism, as well as the interpretation of it as being prophetic of the Shoah, or instead, its many verses as a depiction of Jewish life in interwar Europe, let alone what Professor Weingrad terms “our own moment”.

Fourth, a brief discussion of technical and linguistic aspects of the poem’s translation.

Of course, fifth and last is the poem itself. I shall not “copy and paste” it here, given its very presence at Mosaic and questions about copyright. (One more time, here’s that link!) Suffice to say that Professor Weingrad’s translation comprises approximately 490 lines of text, its structure and organization following that of the Yiddish original. As he states, “I have tried, with a few exceptions, to follow its alternations between iambic sections (“…the rhythm, or meter, established by the words in each line…”) and galloping dactylic ones (“…a long syllable followed by two short syllables, as determined by syllable weight.”)”

“In the Crucifix Kingdom” is only one of the very many poems comprising Uri Tzvi Greenberg’s body of work. It is my understanding that – alas! – his collected poems have never appeared in their totality in English. Fortunately (!), the situation in Hebrew is unsurprisingly different. Lists of the poet’s books of poetry, and, his writings (the latter edited by Dan Miron and published by Mossad Bialik) can be found here. The titles of these works, translated to English via Oogle translate, follow:

Poetry

Great Horror and the Moon (1924)

אימה גדולה וירח

The Rising Ladies (1926)

הגברות העולה

One Vision of the Legions (1928)

חזון אחד הליגיונות

Ancrown – on the Nerve Pole (1928)

אנקראון על קטב העצבון

Towards ninety-nine – a literary essay (1928)

כלפי תשעים ותשעה – מסה ספרותית

Magen Zone and Son of the Blood Speech (1929)

אזור מגן ונאום בן הדם

House Dog (1929)

כלב בית

The Book of Faith and Faith (1937)

ספר הקטרוג והאמונה

The Streets of the River / The Book of Gods and Power (1951)

רחובות הנהר \ ספר האליות והכח

Writings of Uri Zvi Greenberg, edited by Dan Miron

Volume I Poems, Part One

Great horror and moon

The rising ladies

Ancrown on the nerve pole

Volume II Poems, Part Two

One vision of the legions

House dog

Shield area and speech of the blood

Volume III Poems, Part Three

The Book of Katrog and Faith

Volume IV Poems, Part Four

A collection of poems, 1982-1983

Volume V of Poems, Part Five

The streets of the river, Part I

Volume VI Poems, Part Six

The streets of the river, Part II

Volume VII Poems, Part Seven

The book of pages, part I

Volume VIII Poems, Part Eight

The book of pages, Part II

Volume IX Poems, Part Nine

The circle book

Volume X Poems, Part Ten

Espaklar Poems / Bhai Alma

Volume XI Poems, part Eleven

About time and place

Volume XII Poems, Part Twelve

For section Sela Itam [a]

Volume XIII Poems, Part Thirteen

Keys to volumes I-XIII

For section Sela Itam [b]

Handbook of Drawings

Letter and image (edited by J. Ofrat)

Volume X Essays, Part One

About to appear:

Volume XVI Essays, Part Two

For brevity (!) I’ve listed just thirteen journal and internet references about Uri Greenberg at the “end” of this post, one of which includes Professor Weingrad’s translation. Notably, Yosef Galron-Goldschlager’s “Lexicon of the New Hebrew Literature” (in Hebrew) has an enormous list of references about Uri Greenberg.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Here is a snippet of text about Jewish soldiers in the Austro-Hungarian army from my brother blog, TheyWereSoldiers: “Yiddish and Hebrew poet, essayist, and writer Uri Zvi Greenberg (Hebrew: אורי צבי גרינברג), during his service in the Austro-Hungarian army. This photo is from Zeev Galili’s Blog, Logic in Madness (היגיון בשיגעון), within his April 20, 2009 post Uri Zvi Greenberg – the poet who predicted the Holocaust (אורי צבי גרינברג – המשורר שחזה את השואה).

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

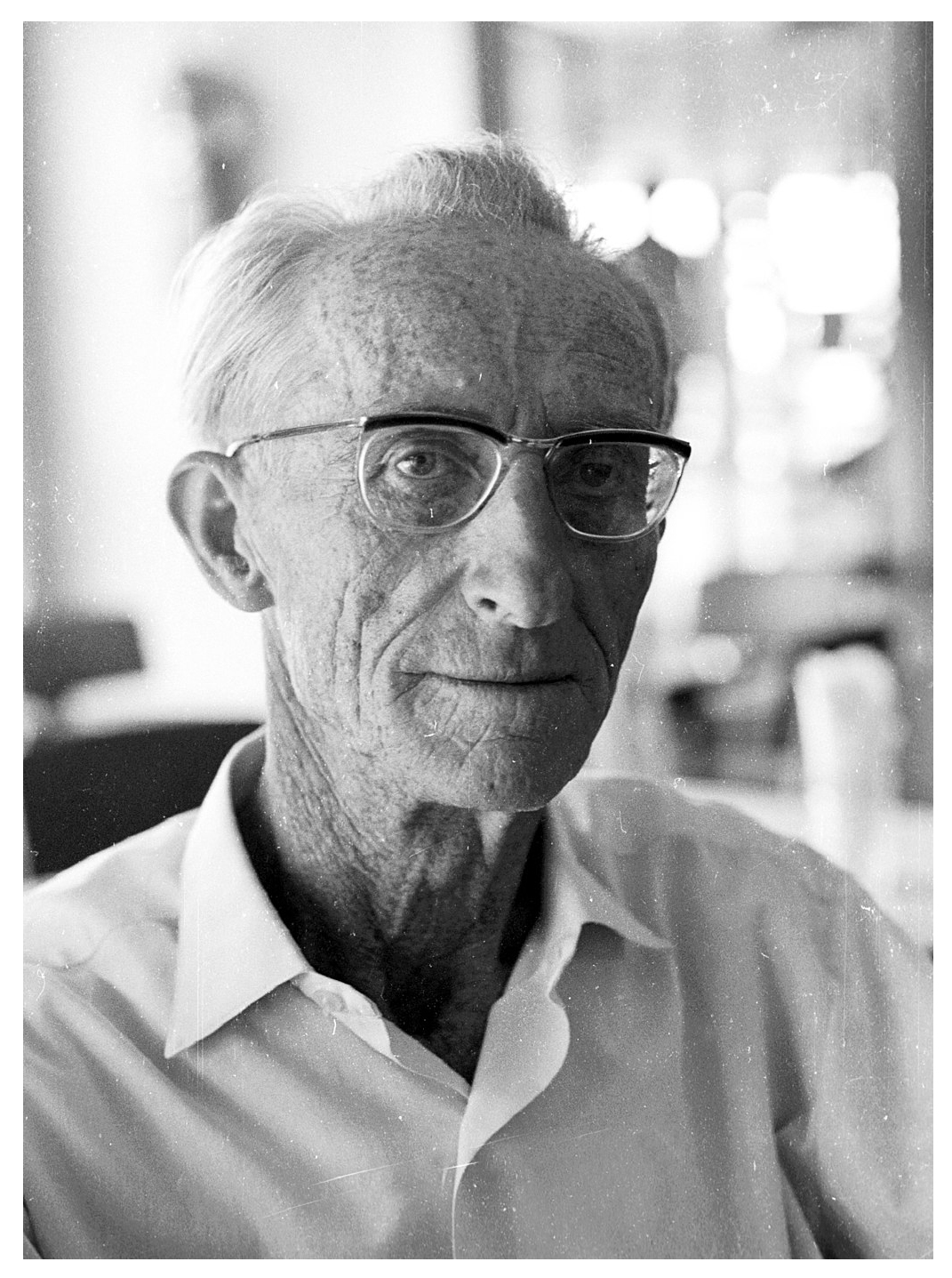

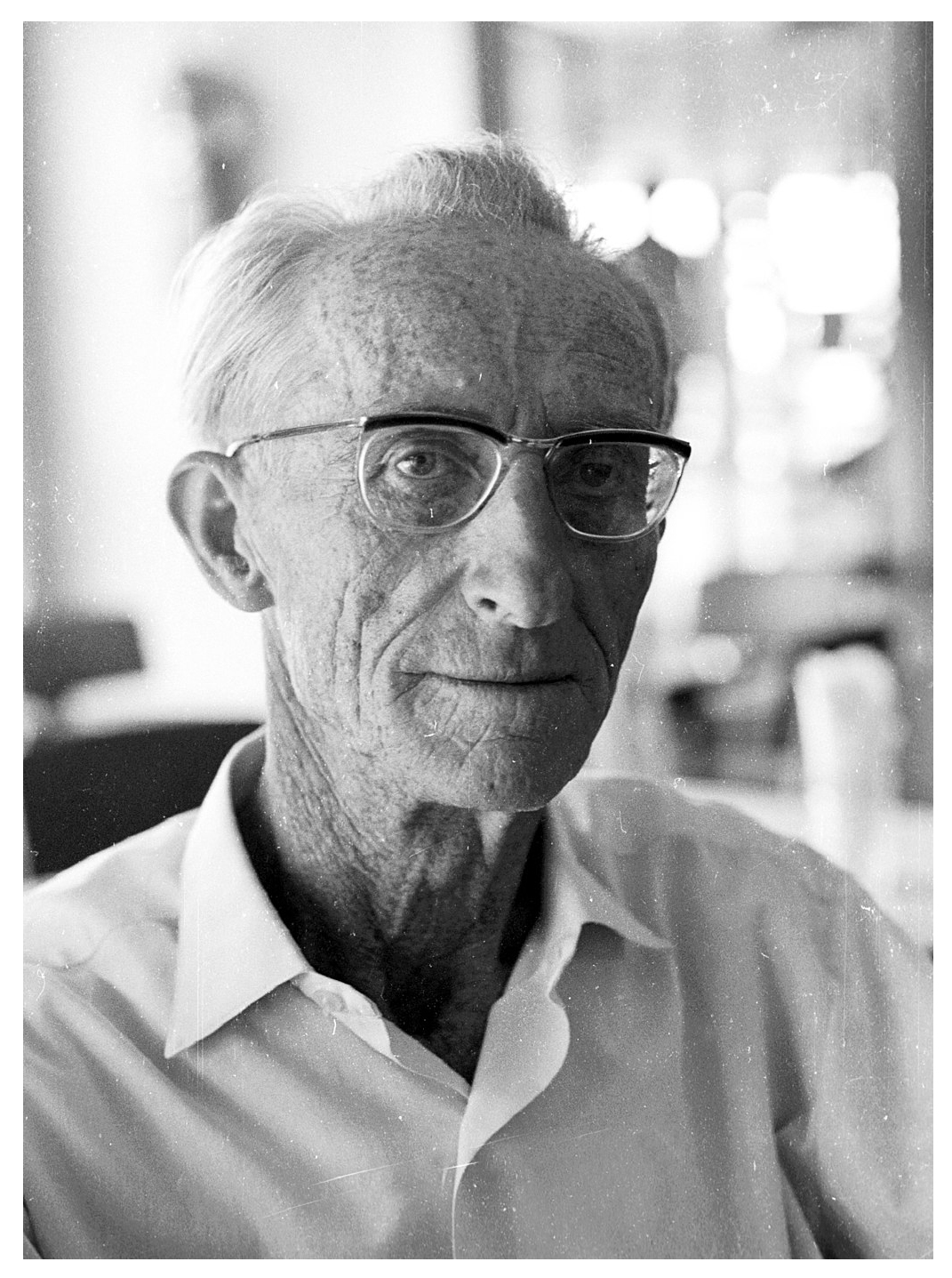

Uri Zvi Greenberg, Tel Aviv, Israel, September 15, 1967 (Photo by Dan Hadani, via Wikimedia Commons; Copyright © IPPA 01773-000-18)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Well, what good is a blog post about Uri Tzvi Greenberg without a examples of his work? Here are excerpts of two of his poems from 1928. The first of the two directly relating to his military service in the First World War, while the second may (?) refer to reflections on the poet’s early effort to compose poetry in Hebrew, rather than in Greenberg’s mother-tongue, Yiddish.

The Remembrance of Souls (Hazkarat neshamot)

1928

…feet up on the barbed wire,

Only the thin wail of their life’s dying essence drawn out,

Then they died, very dark.

I stood alone, like the last of the human race fighting in the world,

And I saw my brothers growing legs in the air,

Until they came in their death to kicking in the sky:

I saw the moon, as if alive, scratching its silver face

On the blunted hobnailed soles of overturned soldiers.

This terrible radiance on these nails of the dead who kick the sky

Electrified my life with terror that gleamed unto death.

With eyes of flesh I saw man’s fall, and the Divine in the mystery of fear.

As the last of those who weep, I wept there mightily.

In all my life I shall never weep again as I wept by the waters of the Sava. (5-6)

Now the rain has stopped and the moon has come out, a double moon –

The mounds of bodies in quicklime in the cruelty of this moon’s bright light!!

There is no ladder

standing on the ground and the angels of our youth do not descend it

to overcome the quicklime and to pray a requiem.

We dig out sand and pour over the bodies in quicklime.

Now when there is a mound and our comrades are buried (temunim)

the priest comes… (13)

To my mind both sides of the warring armies

of Emperor and King were enemies to my race and my creed

but the sight of the faces on these bleeding bodies after they died

aroused my compassion and my tears were purer than dew. (15)

These lasses in the fullness of the juice of the fruit of the tree and the vine

stand there in the water that is like pure crystal, gurgling and gurgling and gurgling,

pure, warm and soft, pure and soft… (16)

…while they are the sons, and they are the husbands,

crouching here in a battlefield in a strange land,

the cold of the morning like alcohol in the throat. (16)

References

Greenberg, Uri Zvi, Kol kvite, edited by Dan Miron, Jerusalem, Mossad Bialik, 1992, V. 1, p. 138

From: The Wound of Memory: Uri Zevi Greenberg’s “From the Book of the Wars of the Gentiles”, by Glenda Abramson, Shofar, V 29, N 1, 2010, pp. 5-6, 13, 15, 16

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Between Blood and Blood (Ben Damim le Damim)

1928

Ay ‘tis thus,

This is not my mother-tongue, which I’ve cut

Like a living limb from the soul, from her view,

from her tune, from the smell of her forest.

My poem’s tongue is the blood-tongue of the wandering race,

Which we have silenced for generations with myriad letters

and that even precious qualities are dwarfed in her light.

References

Greenberg, Uri Zvi, Kol Ktavav (Complete Works), Vol. I (Jerusalem, Mosad Bialik, 1990), p. 7.

Stahl, Neta, “ ‘Man’s Red Soup’: Blood and the Art of Esau in the poetry of Uri Zvi Greenberg,” in Mitchell Hart (ed.), The Significance of Blood in Jewish History and Culture (London and New York: Routledge: 2009), p. 162

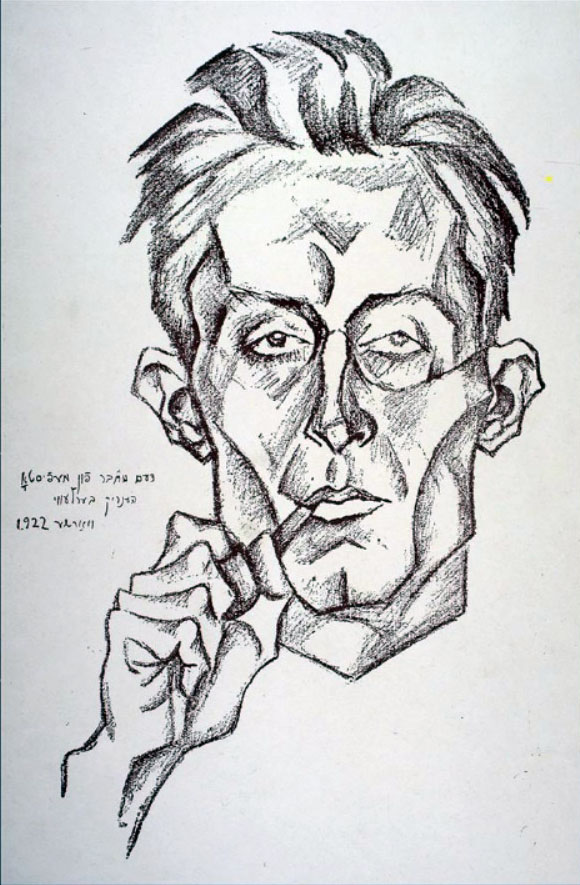

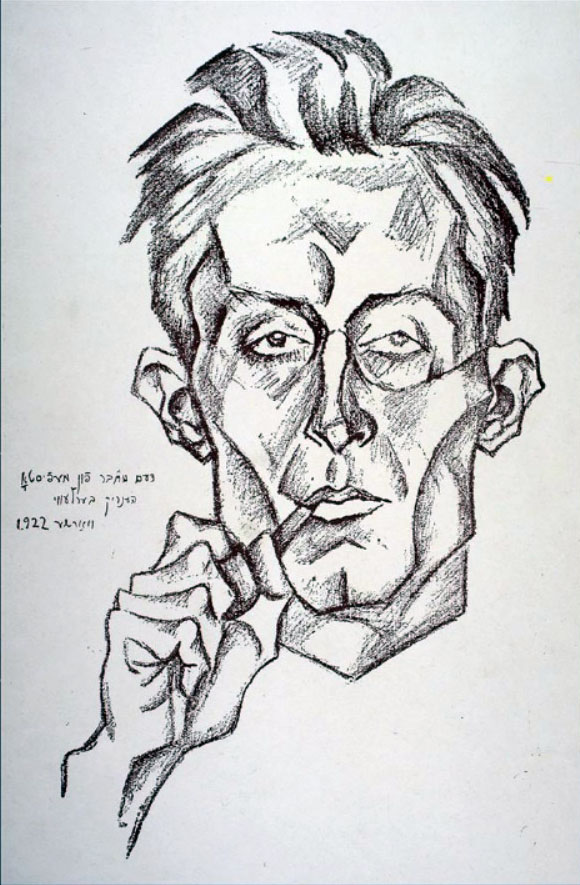

This sketch of Uri Greenberg accompanies his biography (by Dan Miron) at YIVO, with the following caption: “Portrait of Uri Zvi Grinberg, Warsaw, 1922, by Henryk Berlewi, This drawing appeared in Grinberg’s book of poetry, Mefisto (Warsaw: Farlag “Literatur-fond” baym Fareyn fun Yidishe literatn un zshurnalistn in Varshe, 1922). From Joe Fishstein Yiddish Poetry Collection, Rare Books and Special Collections, McGill University Library.”

Within Dan Miron’s biography of Greenberg at YIVO is a discussion of the poet’s completion in 1921 of a “grand scale poema, or a long sequence of poems, in which the weltanschauung (“…worldview or … fundamental cognitive orientation of an individual or society encompassing the whole of the individual’s or society’s knowledge, culture, and point of view.”) … was expressed in an intensely personal and yet universal philosophical manner … titled “Mefisto”. This is described by Miron as being “organized around a myth in which an inverted version of the Faust-Mephisto theme as developed by Goethe and the Nietzschean myth of God’s demise were conflated,” the narrator eventually “dimly” realizing that Mephisto is his “own creation, a projection of his own vitiated interiority, a psychological rather than a metaphysical entity.”

Again quoting Miron:

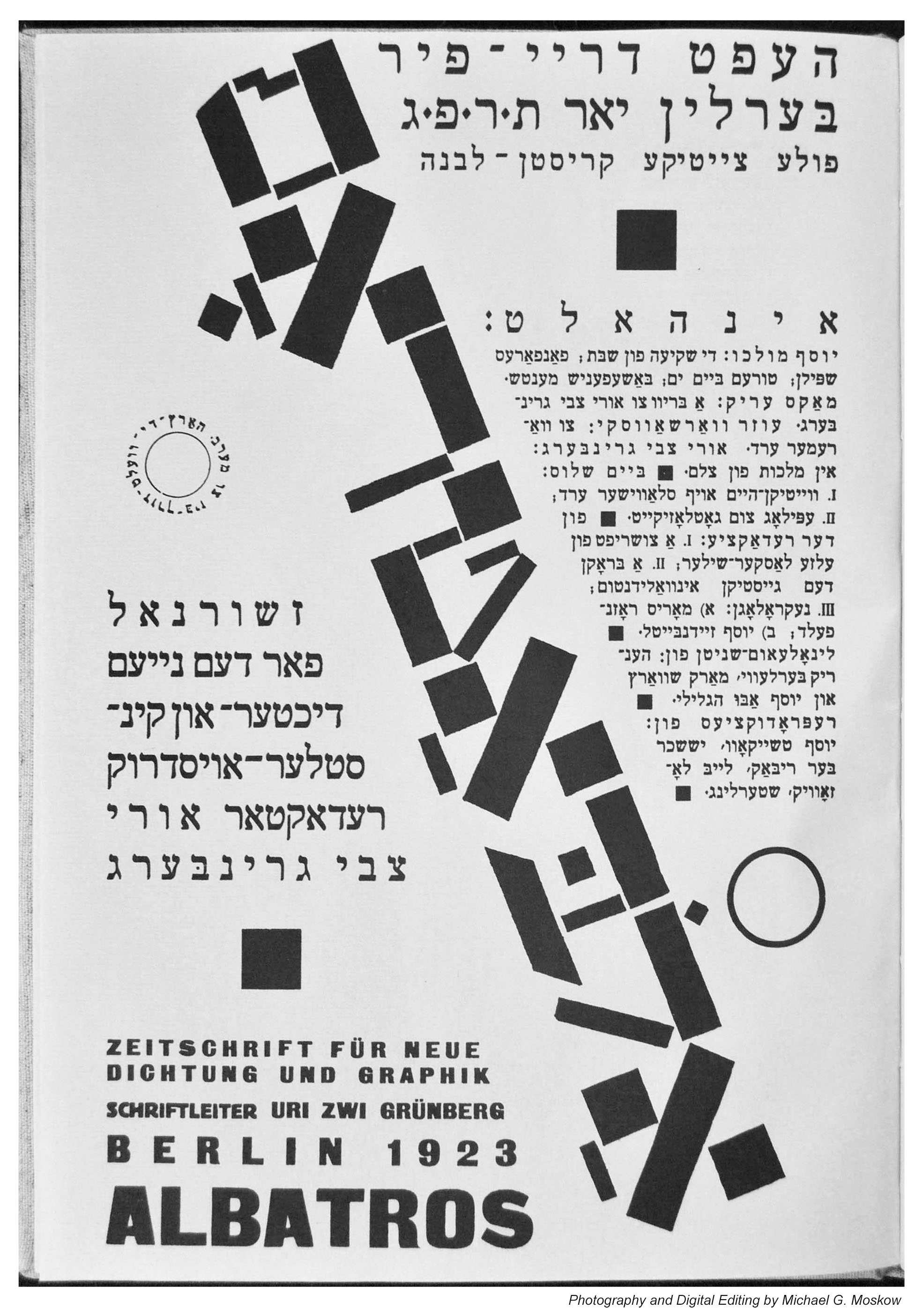

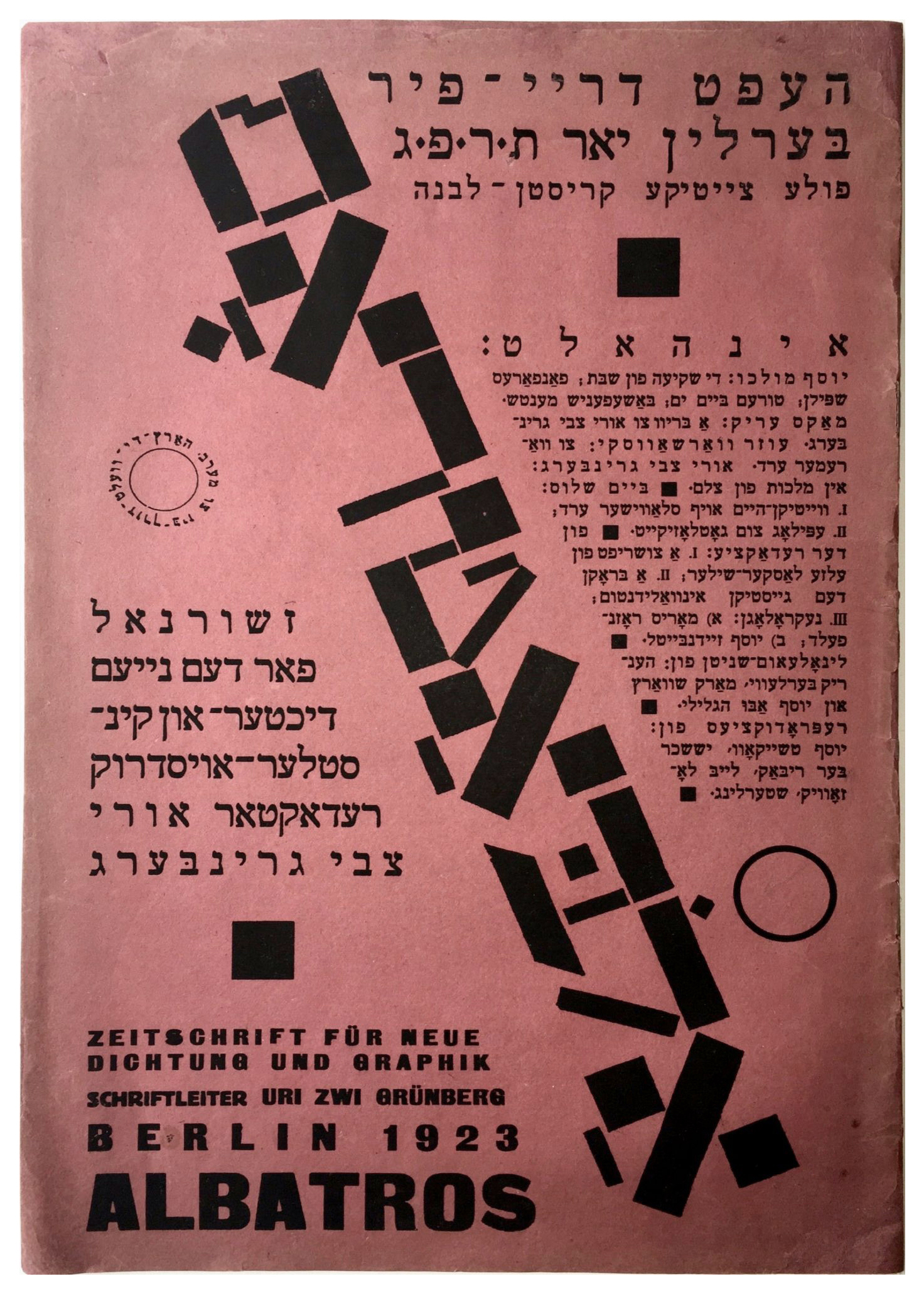

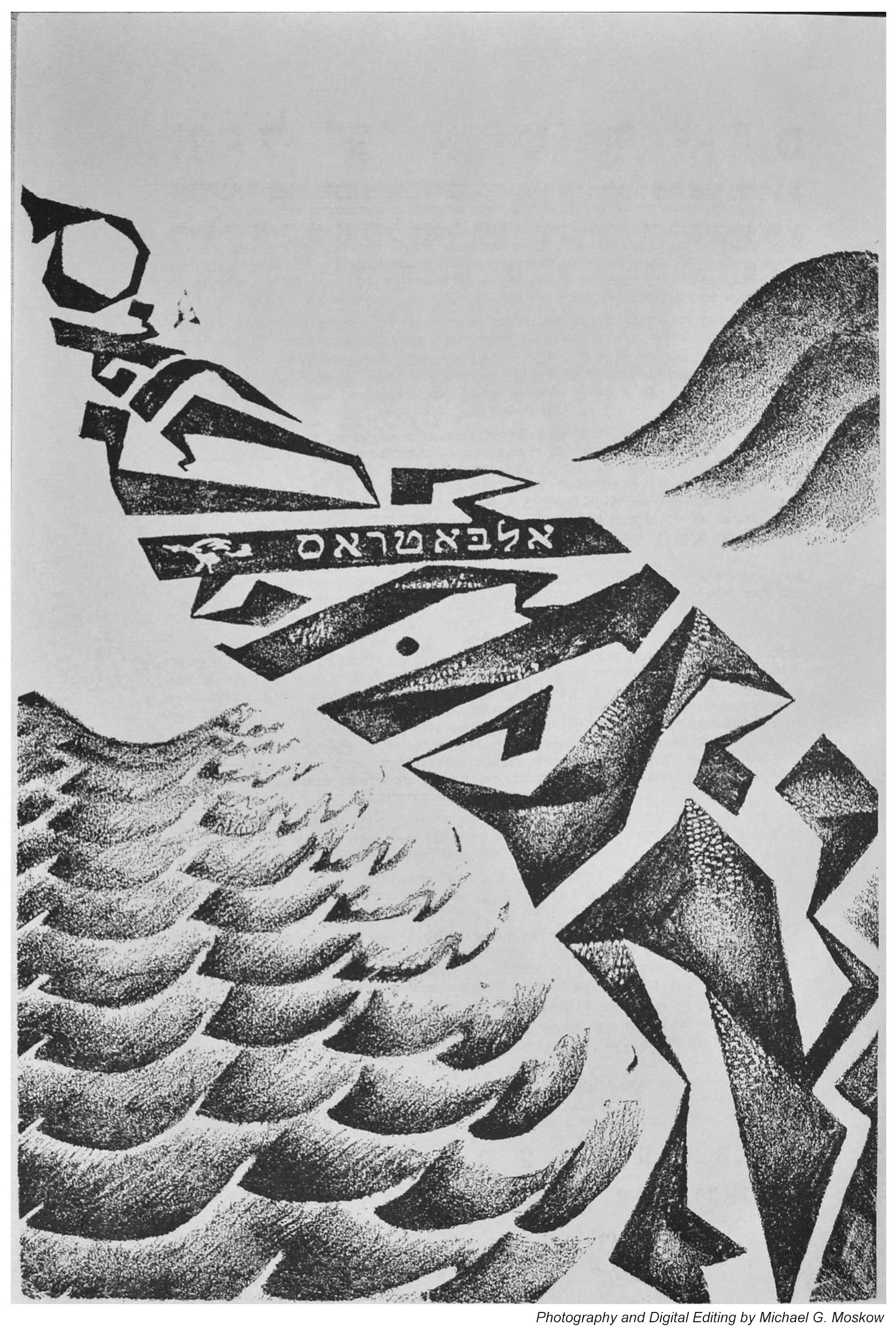

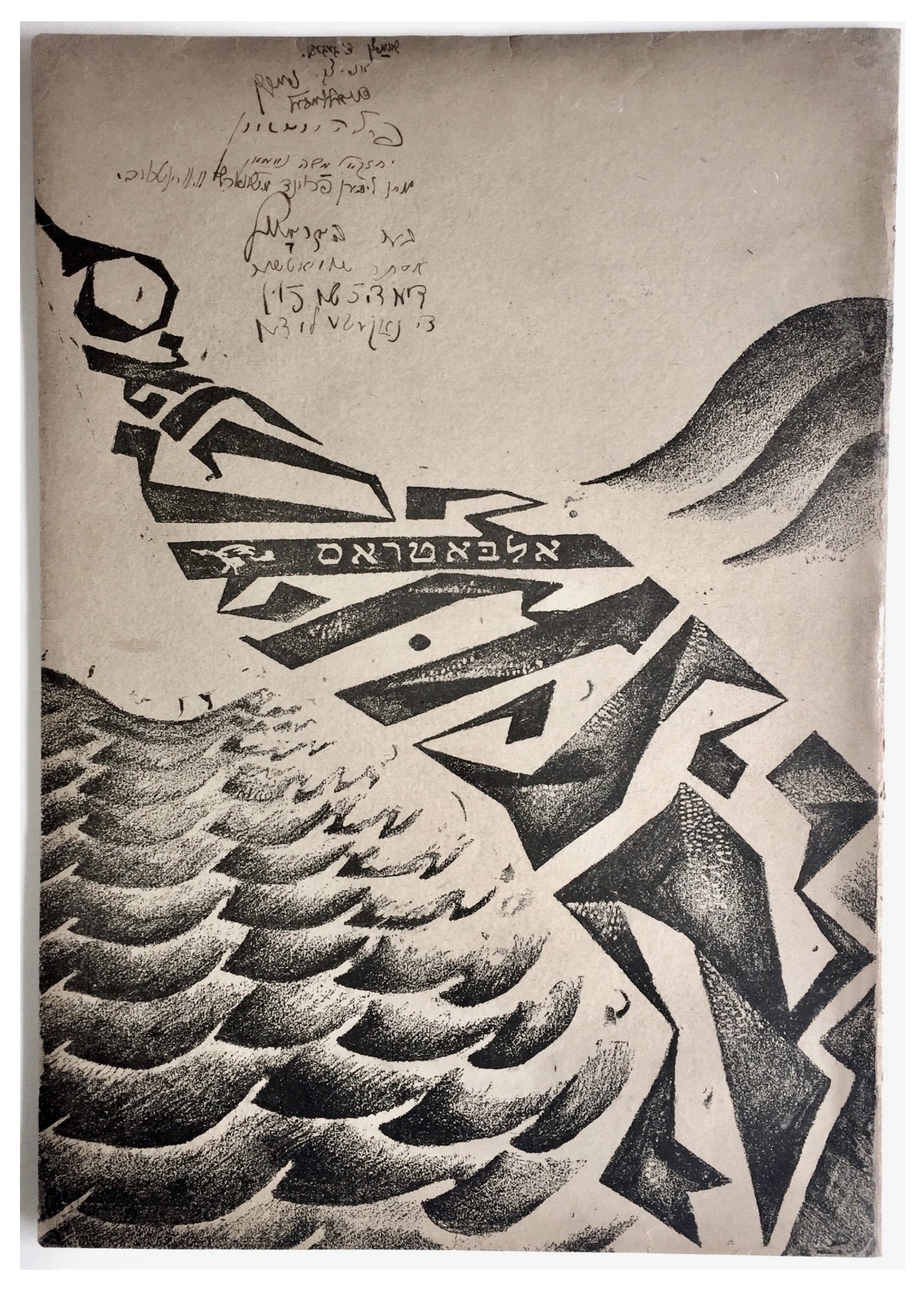

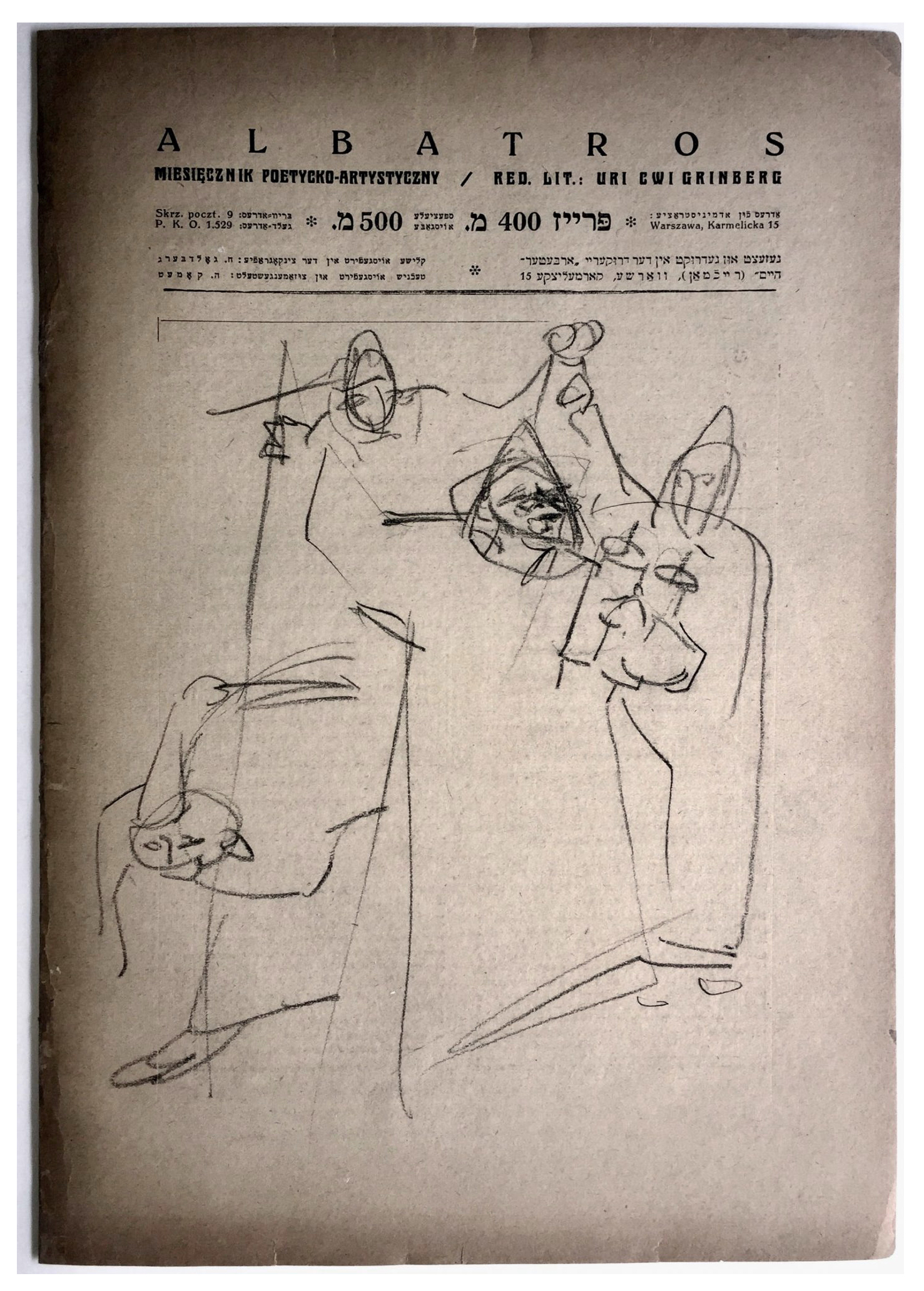

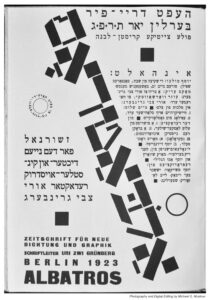

“The publication of Mefisto elevated Grinberg to the rank of a major modernist who could now establish a literary periodical, Albatros (recalling Baudelaire’s famous poem), which was essentially a one-man vehicle. Most of the three issues (1922–1923) were written by Grinberg himself under various pseudonyms. They included – as mentioned above – poems, articles, and manifestos, plus the brilliant short story “Royte epl fun veybeymer” (Red Apples of Trees of Pain), which represents Grinberg’s first radical expressionist treatment of his experiences at the Serbian front. The poet’s main collaborators in Albatros were modernist Jewish artists whose expressionist typographic designs complemented the texts.”

“In 1923, Grinberg had to flee Poland because the Polish censor, scandalized by “Royte epl,” intended to charge him with blasphemous expressions against Christianity. (According to Wikipedia – referencing Yitshak Ḳorn’s “Jews at the Crossroads” (February, 1983), and “The World of Yiddish, Khulyot 1 (Winter 1993)”, at yiddish.haifa.ac.il) the impetus for this charge was Greenberg’s “iconoclastic depictions of Jesus” in the aforementioned poem. The magazine incorporated avant-garde elements both in content and typography, taking its cue from German periodicals like “Die Aktion” and “Der Sturm”.)

“(Grinberg) fled to Berlin where he mingled with German and Jewish modernist writers and artists and became friendly with the German Jewish expressionist poet Elsa Lasker-Schüller, whom Grinberg regarded as a Hebrew poet “in captivity,” a latter-day biblical Deborah. More important, the poet gradually abandoned the nihilistic mood of his Warsaw years. He became convinced that the fate of European Jewry was sealed. Zionism was therefore the only way open to Jews who were not ready for a collective suicide.”

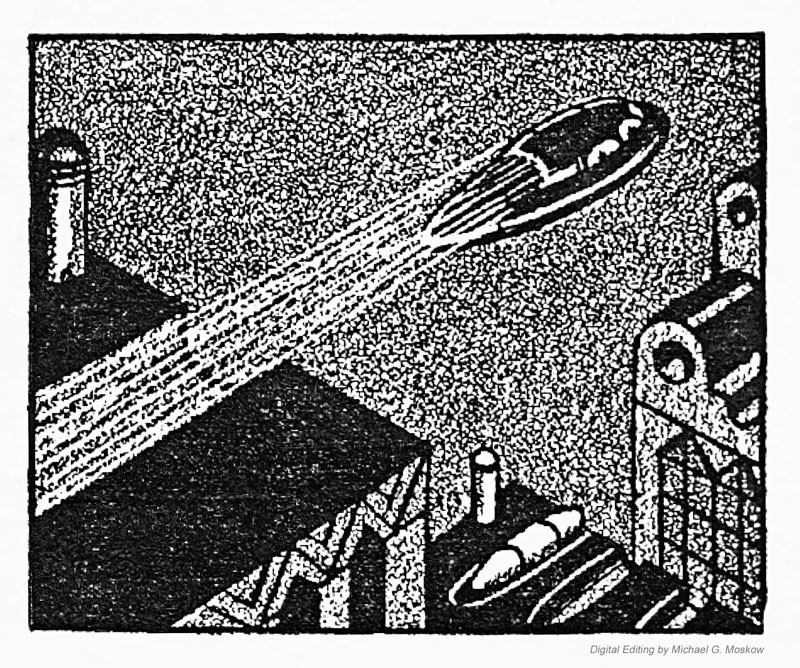

The flight of the Albatross (actually, “Albatros”!)

“In the second half of 1923 Grinberg shifted his writing from Yiddish to Hebrew, took leave of his Yiddish readers in the last issue of Albatros, and arrived in Palestine in December of that year, a committed poet-pioneer. Even before his emigration to Palestine, however, the poet had found himself in the radical camp of Zionist opposition to the leadership of the World Zionist Organization. He feared that a Zionist leadership that did not openly and vigorously strive to establish a Jewish state in Palestine was bound to fail both politically and financially. It was clear to him that the leadership of the Zionist movement had to be summarily replaced by a group of young cadres whose sole objective would be to build an independent Jewish state.”

Now…this intrigued me. I was taken aback by the power, uninhibited moral honesty, and iconoclasm of “In the Crucifix Kingdom” and his other poems (particularly “Uri Zvi in Front of the Cross INRI (Jesus the Nazarene King of the Jews)”, in the latter of which the poet’s searing text is arranged in the form of a crucifix. I wanted to learn more – much more – about Uri Greenberg and, his Albatros.

Though images of pages from original runs of periodical can readily be found on the Internet (most often the cover page of all three issues; typically at the websites of booksellers specializing in Yiddish and Hebrew books, or, rare-books-in-general), none of the three issues are available in their entirety in any digital format. However, to my happy surprise, I discovered that a 1978 reprint of the three issues comprising the publication was (is) available at the New York Public Library, specifically at the Library’s Dorot Jewish Division. A copy of its catalog entry follows:

Title:

אלבאטראס.

Albaṭros

Publication:

[i.e. 1977 or 1978 738] [ירושלים : בית הספרים הלאומי והאוניברסיטאי ]

[Yerushalayim : Bet ha-sefarim ha-leʻumi ṿeha-universitaʻi, 738 i.e. 1977 or 1978]

Further Details

Additional Authors:

גרינבערג, אורי צבי, 1896-1981

Greenberg, Uri Zvi, 1896-1981.

Publication Date:

Hefṭ 1 (Sept. 1922)-3/4 (1923).

Description:

19, 19, 28 p. : ill.; 36 cm.

Subject:

Yiddish literature > Periodicals

Note:

“Zshurnal far dem nayem dikhṭer un ḳinsṭler oysdruk.”

Linking Entry (note):

Reprint, with new explanatory material inserted, of a journal published 1922 in Warsaw and 1923 in Berlin, edited by U.Z. Greenberg.

Call Number:

**P+ 07-42

LCCN:

78647698

OCLC:

4680020

NYPG07-S2

Title:

Albaṭros.

Alternate Script for Title:

אלבאטראס.

Imprint:

[Yerushalayim : Bet ha-sefarim ha-leʻumi ṿeha-universitaʻi, 738 i.e. 1977 or 1978]

Alternate Script for Imprint:

[ירושלים : בית הספרים הלאומי והאוניברסיטאי, [738 i.e. 1977 or 1978]

Linking Entry:

Reprint, with new explanatory material inserted, of a journal published 1922 in Warsaw and 1923 in Berlin, edited by U.Z. Greenberg.

Added Author:

Greenberg, Uri Zvi, 1896-1981.

Alternate Script for Added Author:

גרינבערג, אורי צבי, 1896-1981.

Research Call Number:

**P+ 07-42 Library has: Hefṭ 1 (Sept. 1922)-3/4 (1923).

**P+ 07-4

Here are further details about the editorial and artistic staff of Albatros, and, the date and place of publication of all three issues, from two perhaps-unusual (?!) sources: A bookseller, and, and auction house.

Bookseller: Foldari Books

First… In December of 2018, Földvári Books (Hungary) offered an entire set for sale; all since sold. These particular issues belonged to Marek Szwarc, the periodical’s chief illustrator, and were signed by its seven contributors … “and other members of the modern Yiddish movement: Grinberg [himself], Daniel Leyb, Peretz Hirschbein, Yehezkel Moshe Neiman, Ze’ev Weintraub, Ber Horowitz and Esther Shumiatcher.” The first two issues were published in Warsaw and the last in Berlin. Albatros was “named after Baudelaire’s poem, [and] is the most thoroughly Expressionist journal among the Yiddish avant-garde magazines (“Yung Yiddish”, “Ringen”, “Khalyastre”, “Di Vog”) that were published between 1919 and 1924, the golden period of the Yiddish avant-garde.” (This catalog entry is no longer available.)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Auction House: Kedem

Second… A previous (and since closed) Kedem auction of a complete set of Albatros (“lot 182”), states the following:

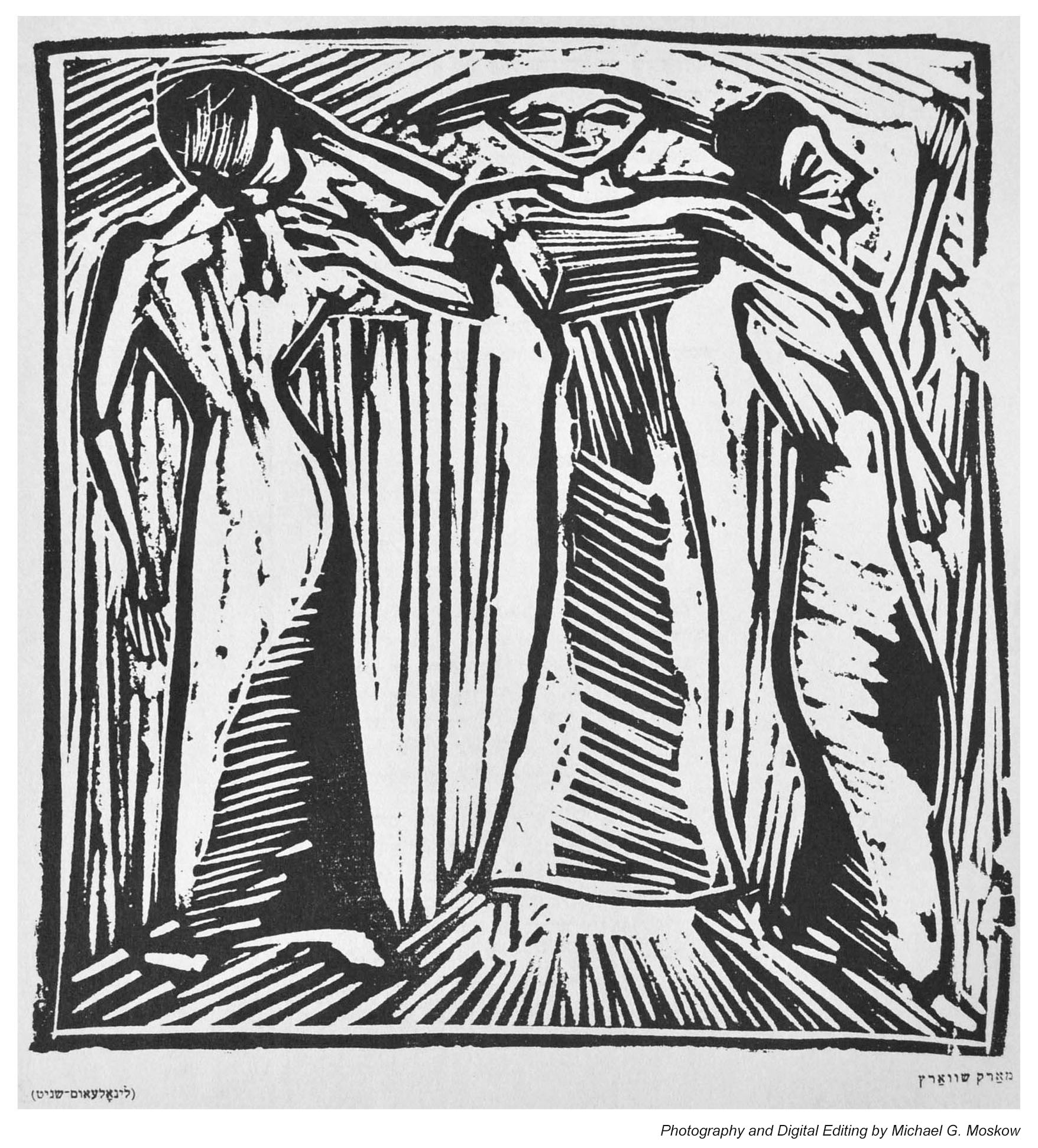

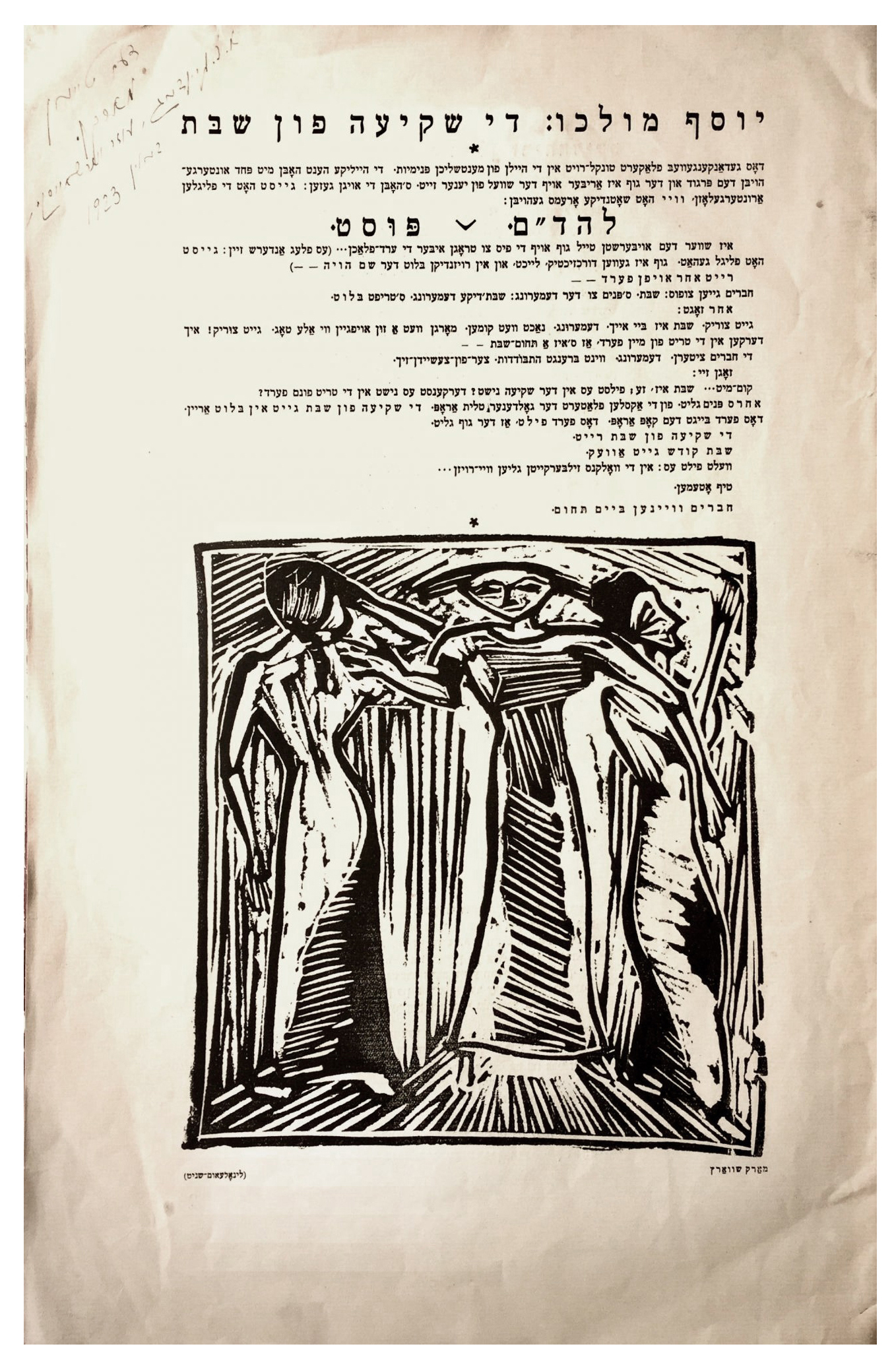

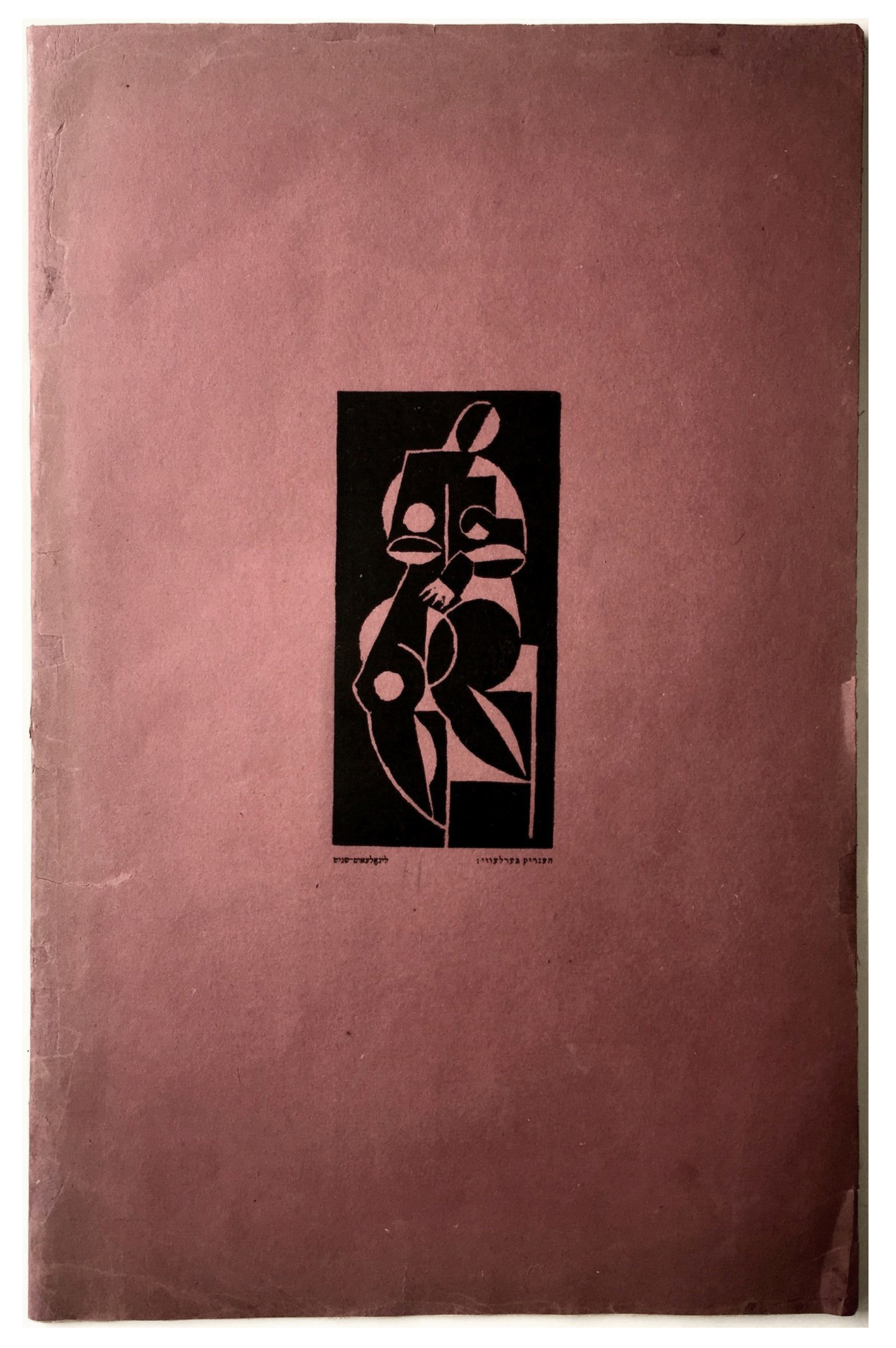

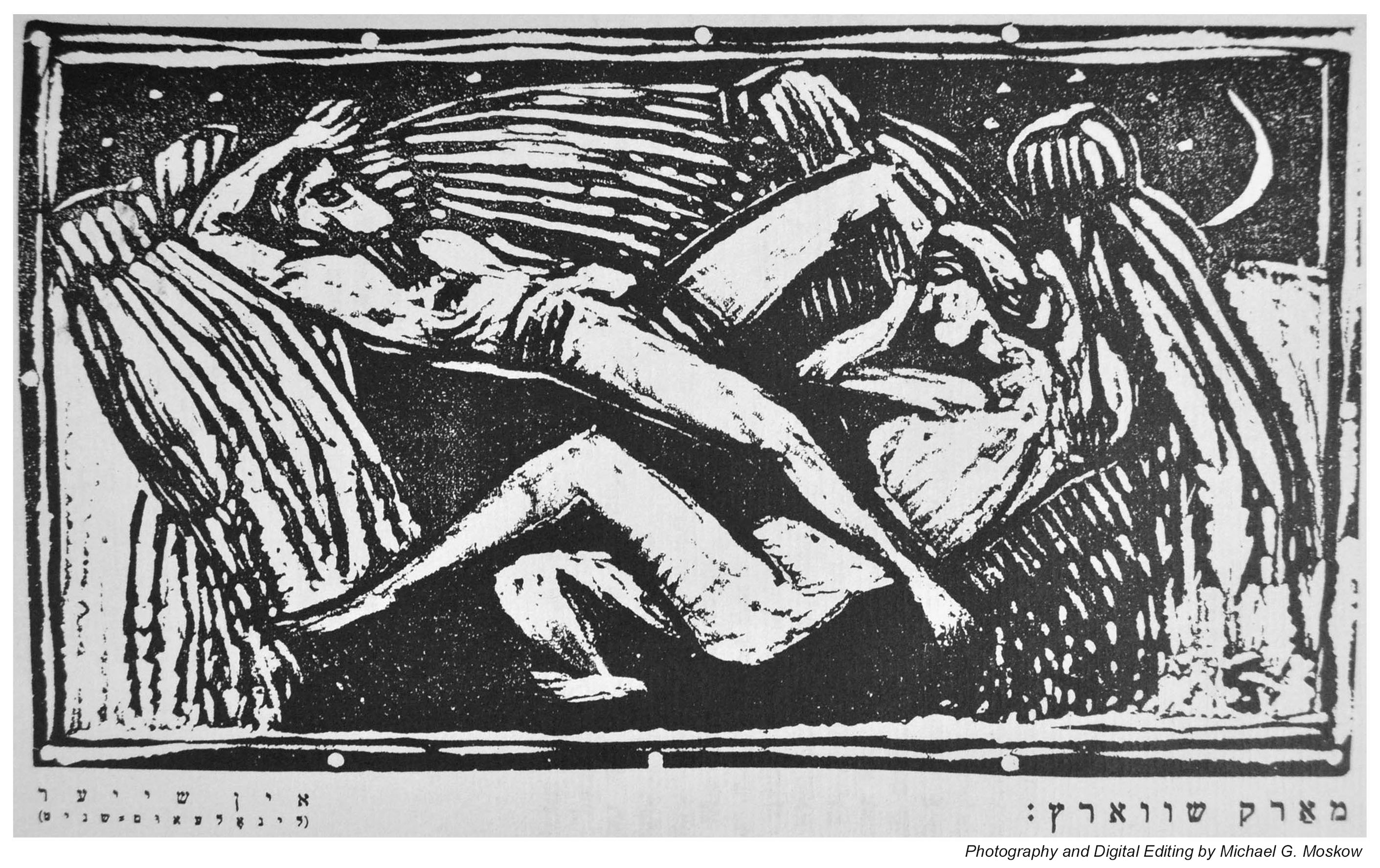

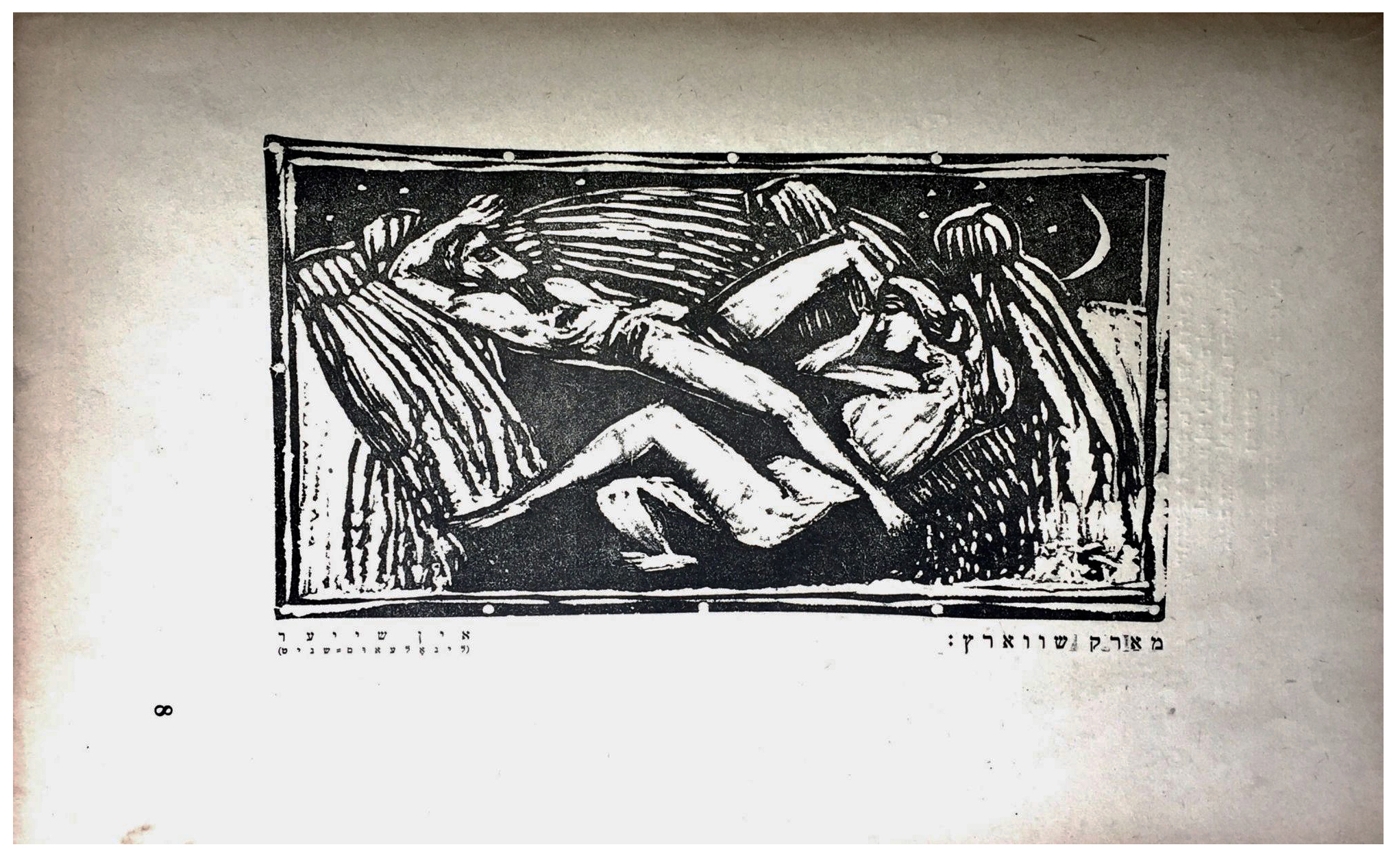

First issue, Warsaw, 1922. Cover designed by Ze’ev (Wladislaw) Weintraub. With linocuts by Marc Schwartz.

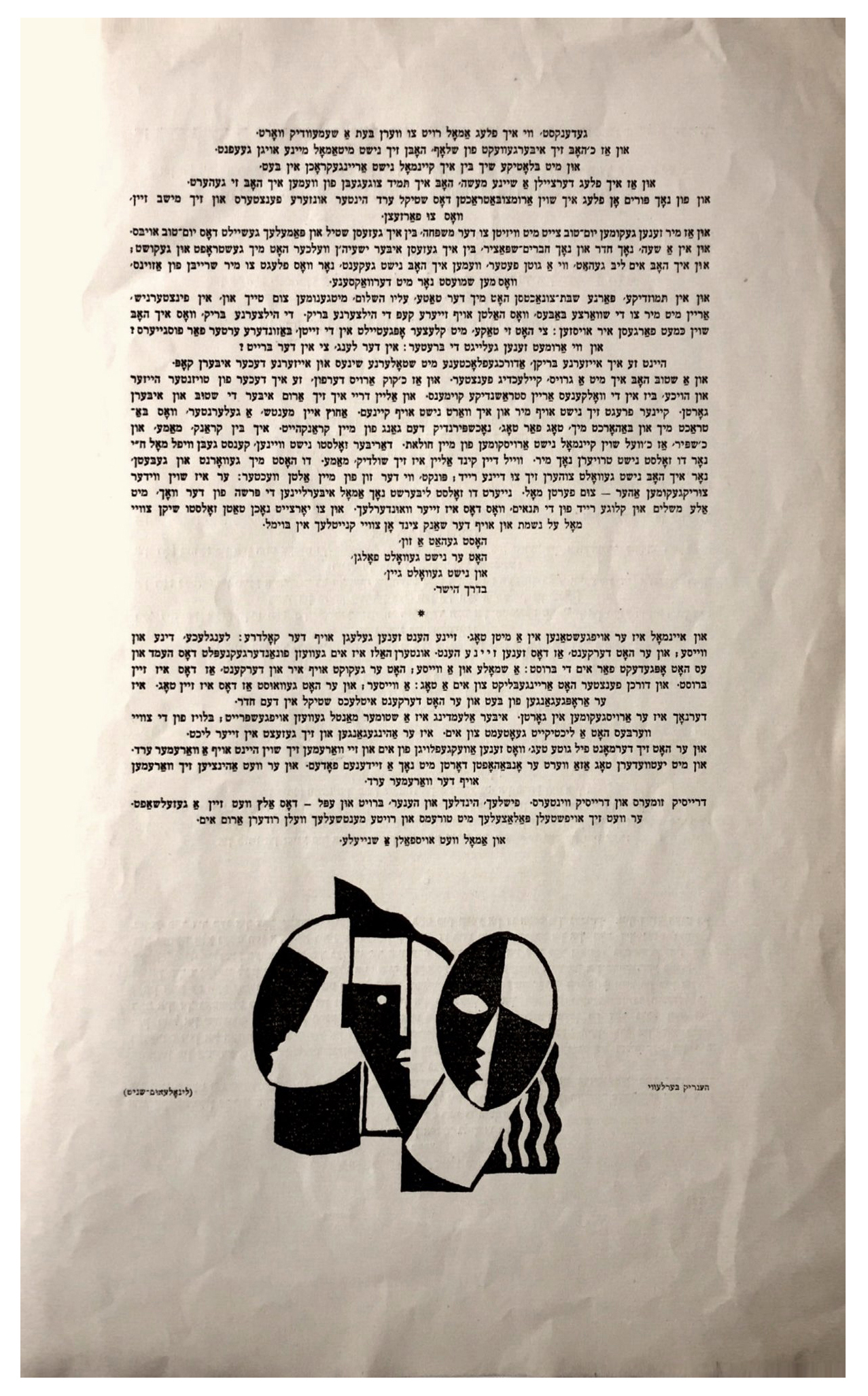

Second issue, Warsaw, 1922. Linocuts on the cover and inside the booklet, by Marc Schwartz [Marek Szwarc].

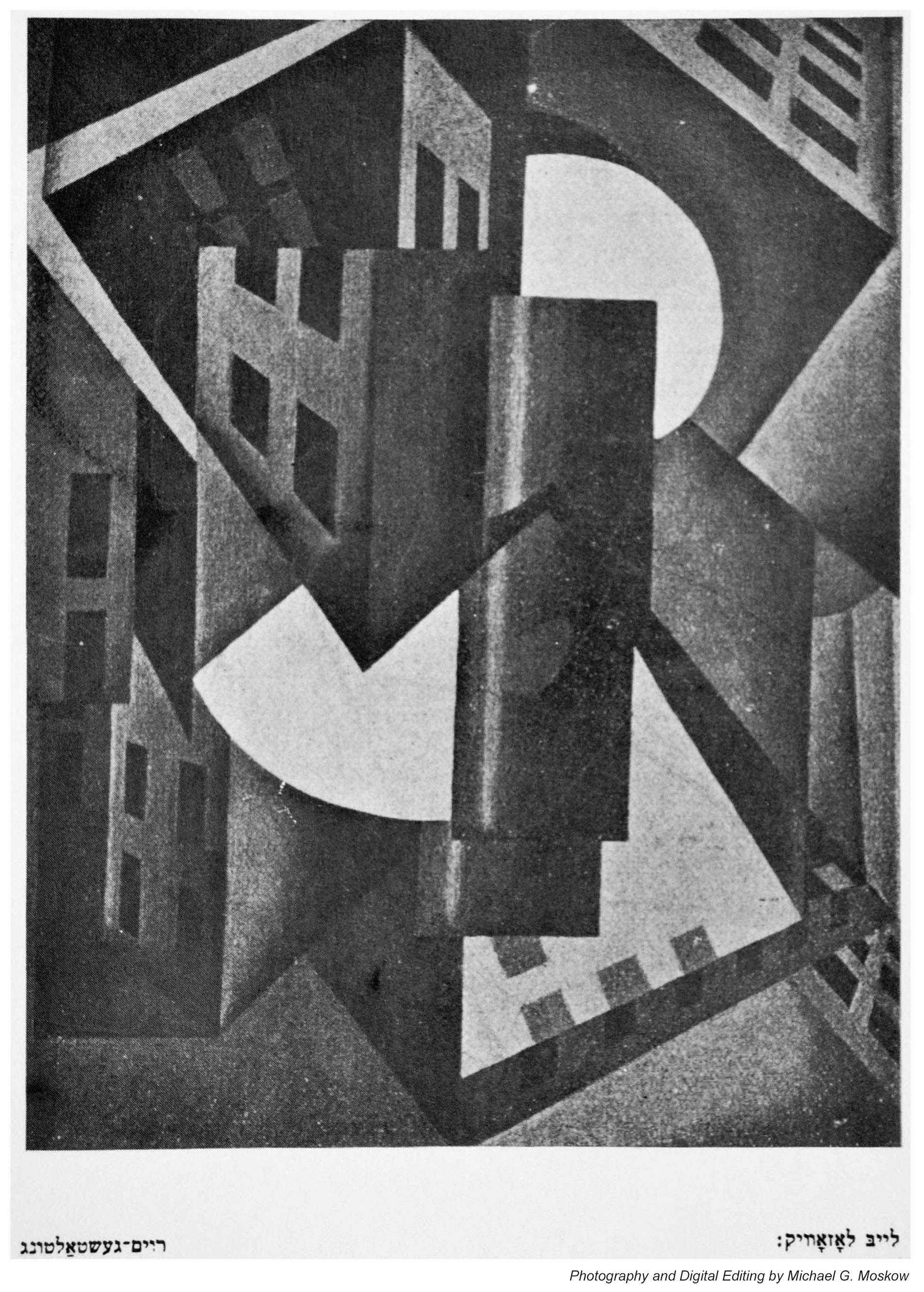

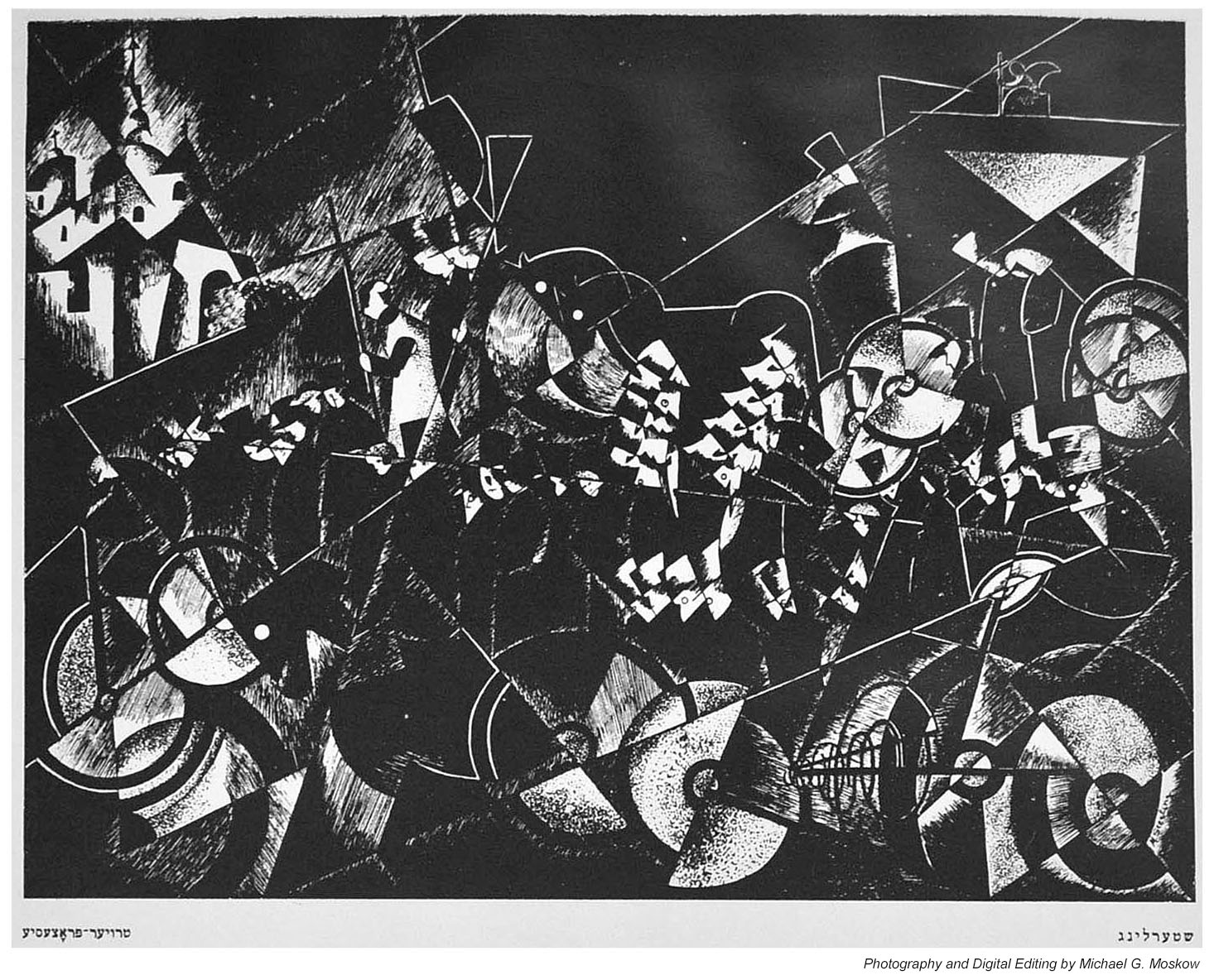

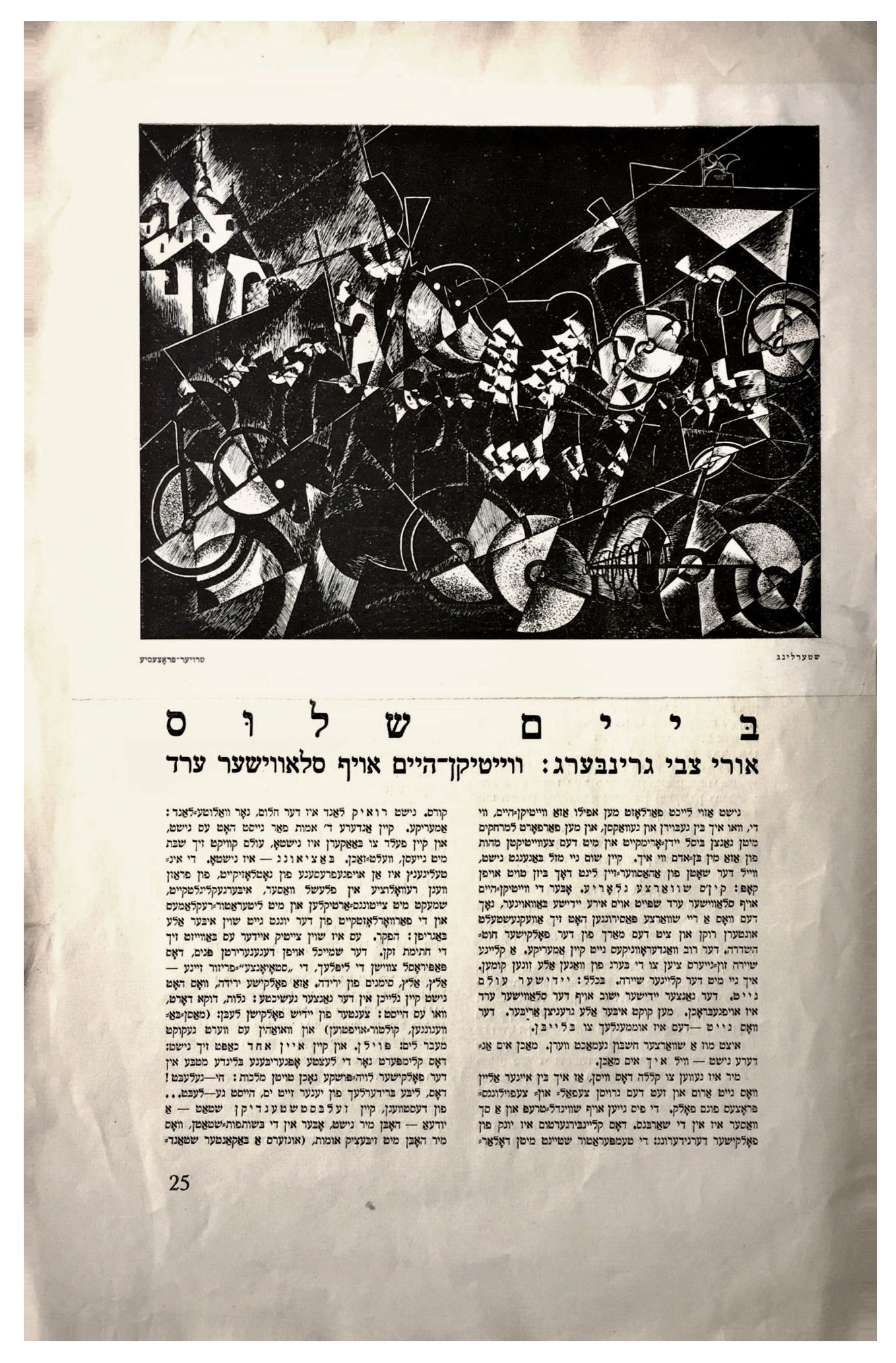

Third and fourth issues, Berlin, 1923. Linocuts by Henrik Berlevi, Marc Schwartz [Marek Szwarc] and Yossef Abu HaGlili. Additional illustrations – reproductions of works by Joseph Tchaikov, Issachar Ber-Ryback and other artists.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Third… Kedem Auctions, in its current offer of the three issues (“lot 209”) provides further information about the periodical and its contributors, the following being derived from its catalog description:

The first issue was dedicated by Uri Zvi Greenberg to Marek Szwarc, and features the manifesto “To the Opponents of The New Poetry” – a revolutionary composition by Greenberg, alongside additional groundbreaking compositions, some of them also written by Greenberg. This issue features a linocut by artist Marek Szwarc, while the cover was designed by Władysław Weintraub.

As for Marek Szwarc (1892-1958) himself? Kedem describes him as having been a, “…Jewish-Polish painter and sculptor, born in Zgierz (Poland); associated with the School of Paris. Szwarc studied at the École des Beaux Arts in Paris and boarded at the artist’s residence La Ruche in the Montparnasse district of Paris, together with Marc Chagall, Chaim Soutine and Fernand Léger. In 1912, he was one of the founders of the art magazine “Mahmadim”, which was considered the first Jewish art magazine. He exhibited his first sculpture in 1913 in the Salon d’Automne. During World War I, he spent some time in Odessa and Kiev (where he met the literary circle of Mendele Mocher Sforim, Achad Ha’am and Bialik and the avant-garde writers headed by David Bergelson), and later returned to Poland, where he was one of the founders of the Yung-Yidish group. Although he converted to Catholicism [irony; irony], his identity as a Jew never wavered and many of his works dealt with biblical themes.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

So, I visited the New York Public Library. And, I took a look.

Entirely consistent with the New York Public Library catalog entry (no surprise there!), I found that the reprint comprises a single volume; it measures 36 centimeters, or a little over 14 inches, in height.

The first of the three reprinted issues is preceded by a statement denoting its (the reprint’s) publication history…

מהדורה זו יוצאת לאור על-ידי הוצאת בית הספרים

הלאומי והאוניברסיטאי בירושלים, בשנת תשל”ח;

הוכנה בגרפיקה אורות ובדפוס אחוה, ירושלים.

בשלוש מאות וחמשים עותקים מסופררים.

חמשים העותקים הראשונים

הופצו ללא תמורה.

עותק זה מספרו

263

…which translates as…

This edition is published by

the National and University Libraries in Jerusalem, in the year 1978;

prepared by Orot Graphics and Ahava Press, Jerusalem.

In three hundred and fifty numbered copies.

The first fifty copies

were distributed free of charge.

This is copy number

263

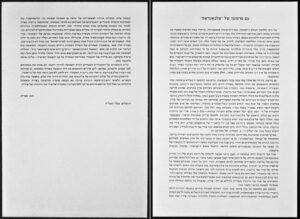

…and is followed by this introduction…

עם פרסומו של “אלבאטראס”

עוד בימי מלחמת העולם הראשונה, בעת התהפוכות שבעקבותיה, ובייחוד נוכח הפרעות שפקדו את היהודים באותו הזמן באירופה המזרחית, עלו בשירת יידיש זרמים חדשניים, שהיתה בהם משום תגובה מיידית למאורעות ולזעזועים עצמם. בשירה נועזת ומרדנית ביקש דור של משוררים צעירים, שהתנסה באופן אישי בזוועות המלחמה והפרעות, להביע את מה שעבר עליו, תוך חיפוש אחרי דרכי הבעה התואמות את התמורות הרגשיות – האינדיבידואליות והיהודיות הכלליות כאחד. עם כל ההסתייגויות המתבקשות בדרך כלל מהגדרות כוללניות ומהצמדת תוויות על פי השתייכות לקבוצה או במה ספרותית זו או אחרת, מצטיינות השנים האחרונות של העשור השני וראשיתן של שנות העשירים של המאה, בריבוי ניכר של פרסומים ספרותיים קבוצתיים חדשניים. קבצים ופרסומים פריודיים קצרי ימים צצו באותו הזמן בכל פזוריה של ספרות יידיש, כאשר בכולם מתבלט משקלה הסגולי והכמותי של השירה המגיבה בעוצמה רבה ובקול רם על מה שהעסיק אז את היחיד ואת הציבור כאחד. בקיוב הופיעו הקבצים של אייגנס (1918, 1920), בלודז ראו אור החוברות של יונג¯אידיש (1919), הגליונות הראשונים של אין זיך הפתיעו בניו¯יורק (1920), וחלק מחבורת קיוב חתרכז מחדש בשטראם (1922) המוסקבאי.

גם בורשה, בירתה של פולין שזה עתה זכתה לעצמאות, עדים אנו לתופעה זו במלוא עוצמתה. אחד הביטויים הראשונים של הרוח החדשה בשירת יידיש ניתן בורשה בכתב-העת רינגען, בחוברת העשירית והאחרונה, מראשית 1922. בחוברת זאת השתתפו בשירתם פרץ מארקיש, שהגיע לורשה מקיוב, מלך ראוויטש, שבא מוינה, ואורי צבי גרינברג, שכבר במחצית השנייה של שנת 1921 כבש בסערה מלבוב הגאליצאית את חסידי השירה הצעירה בספרו מעפיסטא (1921). במהרה החלו להופיע בורשה הפרסומים העצמיים בעריכתם של שלושת המשוררים, שהזדמנו יחד באותה עת לבירתה של פולין. במחצית השניה של שנת 1922 הופיע הקובץ כאליאסטרע (כנופיה), בעריכתו של פרץ מארקיש (הקובץ השני הופיע בפאריז בשנת 1924). באוגוסט 1922 החל מלך ראוויטש לפרסם בעריכתו את החוברות של די וואג (בסך הכל הופיעו שלוש חוברות צנומות – כולן ב-1922). אורי צבי גרינברג הופיע עם הגליון הראשון של אלבאטראס, כתב-עת “להבעה שירית ואמנותית חדשה”, בספטמבר 1922. הגיליון השני של אלבאטראס הופיע בנובמבר אותה שנה והוחרם על ידי השלטונות הפולנים בגלל פגיעה בנצרות, שמצאו ב”רויטע עפל פון וויי-ביימער” של מוסטאפא זאהיב, הוא אורי צבי גרינברג, עורכו של הבטאון. בגלל היותו נתון לאיום במשפט, עקר אורי צבי גרינברג לברלין, ושם הוא הוציא בשנת 1923 את הגליון 3—4, האחרון, של כתב-עת זה.

בפרקי זכרונות ובהערכות ספרותיות מאוחרות קיימת נטייה להציג את ההתפרצות השירית בורשה כהופעתה של קבוצת “כאליאסטרע”, על פי הקובץ בשם זה שבעריכתו של פרץ מארקיש. לשירתם הודבקה התוית של אקספרסיוניזם יהודי. כיון שכל אחד משלושת המשוררים השתתף זה בבטאונו של זה, במשך כל התקופה שבטאוניהם הופיעו בורשה, התקבל אופים ה”קבוצתי”, כביכול, כעובדה מוסכמת.

אורי צבי גרינברג דוחה מוסכמה זו. ואכן, נראה שקשה להעלות על הדעת גיבוש של דרך שירית משותפת תוך הסכמה הדדית, על פי זימון ארעי וקצר שנמשך כשנה בלבד. אך מעל לכל נדמה, שבחינת שירתם של שלושת המשוררים שהזדמנו לאותן אכסניות, תעיד יותר על השוני שביניהם מאשר על שותפות שירית או רעיונית. בשלוש החוברות של אלבאטראס, בהן מתבלט מזגו האישי וייחודה של שירתו של אורי צבי גרינברג, ניתן למצוא עדות מובהקת לכך. כאן הופיעה שירתו הנועזת והנוקבת ביותר של המשורר, וכאן הוא נתן ביטוי ל”אני מאמין” האמנותי והרעיוני שלו בשירתו ובהצהרותיו. כמו קודם לכן במעפיסטא, כך גם בביטאונו אלבאטראס, אפשר למצוא כבר את יסודותיה של שירתו המאוחרת של אורי צבי גרינברג בעברית וביידיש גם יחד; שירה, שבצורה כה בולטת מבדילה אותו מעמיתיו למפגש בורשה משנת 1922.

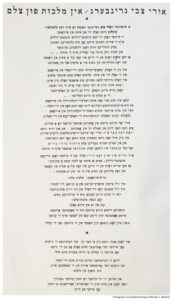

נסתפק כאן בהצבעה על ענין מהותי אחד בלבד. השירה הצעירה ביידיש בתקופה הנידונה היתה ביסודה וברובה שירה אקטיביסטית, למרות מבוכותיה וחיפושיה האינדיבידואליים. מעבר לרצון המכוון לזעזע בשלילותיה ובהתנגדויותיה למוסכמות השולטות בחברה היהודית, הצטיינה שירה זאת, בעת ובעונה אחת, בכמיהה אדירה לאפשרויות של יציאה מן המבוכה שאחזה בה, ובהשתוקקות עזה לפתרונות אישיים וציבוריים. האקטיביזם של מארקיש בא לביטוי באמונתו, שהמהפכה ברוסיה עשויה לפתור את הבעיות שהעסיקו אותו כאדם וכיהודי. זאת, למרות הנימות האמביוולנטיות הברורות בשירותו גם במהלך מהותי ועקרוני זה. אחרים מצאו אפשרויות בפתרונות אוטונומיסטים למיניהם, תוך קבלת הסיסמה של היאחזות יהודית מקומית בארצות הגולה, שנתמצתה במושג של “דאיקייט”. אורי צבי גרינברג נקט עמדה אקטיביסטית אחרת, שהבדילה אותה מכל האחרים, ושלה הוא נאמן עד ימינו אלה. האקטיביזם של א.צ. גרינברג הוביל אותו באופן הגיוני לארץ-ישראל. בכך נבדל האלבאטראס, בצורה חדה מאד, מבטאוניה האחרים של השירה הצעירה ביידיש באותה התקופה. הפואימה עזת הביטוי “אין מלכות פון צלם” והמאמר הפרוגראמאטי “ווייטיקן-היים אויף סלאווישער ערד”, הנילווה לפואימה זאת באלבאטראס הברלינאי, הם גם חשבון-נפש נבואי יהודי ציבורי מחריד ונוקב בעל נימה אישית מובהקת, וגם פרידה של המשורר מאירופה הנוצרית על סף הגשמתו האישית – עליתו ארצה בדצמבר 1923.

ברוב הבטאונים של המשוררים הצעירים ניכרת השאיפה להידור חיצוני. הם פתחו את בטאוניהם לפני אמנים חדשניים, שסיפקו להם איורים התואמים את רוח התקופה בשירה ובאמנות. גם מבחינה זאת הצטיין אלבאטראס, כי אורי צבי גרינברג המשורר, ידע לדאוג לעיצוב גראפי נאה של פירסומיו. בהופעתן מחדש של שלוש החוברות של אלבאטראס, הנדירות ביותר מזה שנים, מאפשר עתה בית הספרים הלאומי והאניברסיטאי היכרות קרובה עם תקופה סוערת ומרשימה בשירה ובאמנות היהודית. אך מעל לכל, פירסום זה הוא שי יקר לכל מעריציו של אורי צבי גרינברג ושל שירתו.

חנה שמרון

ירושלים, כסלו תשל”ח

…which translates as…

With the Publication of “Albatros”

Back in the days of the First World War, during the upheavals that followed it, and especially in view of the disturbances that befell the Jews at that time in Eastern Europe, innovative currents arose in Yiddish poetry, which were an immediate response to the events and shocks themselves. In bold and rebellious poetry, a generation of young poets, who personally experienced the horrors of war and disturbances, sought to express what they had gone through, while searching for ways of expression that corresponded to the emotional transformations – both individual and general Jewish. With all the reservations that are usually required from inclusive definitions and attaching labels according to belonging to one or another literary group or stage, the last years of the second decade and the beginning of the rich years of the century are distinguished by a considerable proliferation of innovative group literary publications. Short-lived periodical files and publications appeared at the same time in all the scatterings of Yiddish literature, where in all of them stands out the specific and quantitative weight of the poetry that responds with great force and loudness to what occupied both the individual and the public at the time. In Kiev, Eygens’s [Eygns] files appeared (1918, 1920), in Lodz the booklets of Yung Yiddish [Yung-idish] were published (1919), the first issues of Ein Zeich [In zikh] [אין זיך] surprised New York (1920), and part of the Kiev group refocused on Stram [Der Shtrom] (1922) in Moscow.

In Warsaw, the capital of newly independent Poland, we are witnessing this phenomenon in full force. One of the first expressions of the new spirit in Yiddish poetry was given in Warsaw in the journal Ringen [Ringen], in the tenth and last booklet, from the beginning of 1922. In this booklet, Peretz Markish, who came to Warsaw from Kyiv, the King of Ravitch [Melech Ravitch], who came from Vienna, and Uri Zvi Greenberg, who already in the second half of 1921 conquered the followers of young poetry by storm from Lviv in Galicia, in his book Maafista [מעפיסטא Mefisto] (Maafista (1921). Soon the self-published publications edited by the three poets, who happened together at that time to the capital of Poland, began to appear in Warsaw. In the second half of 1922, the file appeared as Aliastra (gang) [Khalyastre], edited by Peretz Markish (the second file appeared in Paris in 1924). In August 1922, King of Ravitch [Melech Ravitch] began to publish the pamphlets of De Waag [Di vog] under his editorship (a total of three slim pamphlets appeared – all in 1922). Uri Zvi Greenberg appeared with the first issue of Albatross, a magazine “for a new poetic and artistic expression”, in September 1922. The second issue of Albatross appeared in November of the same year and was confiscated by the Polish authorities because of an attack on Christianity, which they found in “Roite Efel von Wei-Beimer” [“Royte epl fun veybeymer” (“Red Apples of Trees of Pain”)], of Mustafa Zahib, is Uri Zvi Greenberg, the editor of the newspaper [הבטאון]. Because of being threatened with a trial, Uri Zvi Greenberg moved to Berlin, where in 1923 he published issues 3-4, the last, of this magazine.

In chapters of memoirs and later literary evaluations there is a tendency to present the poetic eruption in Warsaw as the appearance of the group “Khaliastra” [“Khalyastre”], according to the file of that name edited by Peretz Markish. Their poetry was labeled Jewish Expressionism. Since each of the three poets participated in each other’s concerts, during the entire period that their concerts appeared in Warsaw, the “group” poetry, so to speak, was accepted as an agreed fact.

Uri Zvi Greenberg rejects this convention. Indeed, it seems that it is difficult to imagine the formation of a common song path with mutual consent, according to a temporary and short summons that lasted only about a year. But above all, it seems that examining the poetry of the three poets we invited to those hostels, will testify more to the difference between them than to a poetic or conceptual partnership. In the three booklets of Albatross, in which the personal temperament and uniqueness of Uri Zvi Greenberg’s poetry stand out, clear evidence of this can be found. Here appeared the poet’s most daring and poignant poetry, and here he gave expression to his artistic and conceptual “I believe” in his poetry and statements. As before in Maafista [Mefisto], so also in his expression Albatross, one can already find the foundations of Uri Zvi Greenberg’s later poetry in both Hebrew and Yiddish; poetry, which so prominently distinguishes him from his colleagues at the 1922 Warsaw meeting.

We will limit ourselves here to voting on only one essential matter. Young Yiddish poetry in the period in question was fundamentally and mostly activist poetry, despite its embarrassments and individual searches. Beyond the deliberate desire to shock with its negations and objections to the conventions that dominate Jewish society, this poetry excelled, at the same time, in its tremendous longing for the possibilities of getting out of the embarrassment that gripped it, and in its strong longing for personal and public solutions. Markish’s activism is expressed in his belief that the revolution in Russia might solve the problems that preoccupied him as a person and as a Jew. This, despite the clear ambivalent tones in his service even during this essential and principled course. Others found possibilities in autonomist solutions of various kinds, while accepting the slogan of local Jewish adherence in the Diaspora lands, which was summed up in the concept of “Daikeit”* [דאיקייט]. Uri Zvi Greenberg took a different activist position, which distinguished it from all the others, and to which he is loyal to this day. The activism of U.Ts. Greenberg logically led him to the Land of Israel. In this, Albatross differed, in a very sharp way, from the other poets of the young Yiddish poetry of the same period. The intense poem with the expression “In The Kingdom of The Cross” [אין מלכות פון צלם] and the programmatic essay “Pain-Home on Slavic Land” [ווייטיקן-היים אויף סלאווישער ערד], which accompanied this poem in the Berlin Albatross, are both a horrific and poignant public Jewish prophetic soul-searching with a distinctly personal tone, and also a farewell of the poet from Christian Europe on the verge of its fulfillment. The personal – immigrated to Israel in December 1923.

In most of the baton of the young poets, the desire for external compilation is evident. They opened their towns to innovative artists, who provided them with illustrations that corresponded to the spirit of the time in poetry and art. Albatross excelled in this respect as well, because Uri Zvi Greenberg, the poet, knew how to take care of a nice graphic design of his publications. With the reappearance of the three Albatross booklets, the rarest in years, the National and University Library now enables a close acquaintance with a stormy and impressive period in Jewish poetry and art. But above all, this publication is a precious treasure for all fans of Uri Zvi Greenberg and his poetry.

Hana Shimron

Jerusalem, Kislev 1978

*“Daikeit” [דאיקייט]: “Its a Yiddish term describing a principle of the Bund (A socialist movement that opposed Zionist attempts to gain self-determination or return to Israel, and opposed pan-Jewish identification too). The principle states that “our home is wherever we live”. A lot can be said about the Bund, there is nuance to it and its not similar to modern “anti-zionist” left-wing groups. I of course disagree with it as a Zionist but if that’s what you are into…. go for it” (From here and here at Reddit)

…and this introduction appears as…

But wait; there’s more to come … much more!

Given the significance of Albatros in terms of Yiddish poetry and Jewish modernism, and in light of the stunning visual symbolism associated with “Uri Zvi in Front of the Cross INRI (Jesus the Nazarene King of the Jews)” I thought (and think) that the periodicals’ content – well, at bare minimum its artistic content – would more than merit presentation to the wider world. To that end, during a visit to the New York Public Library in 2018 (two short years before the 2020 commencement of the metropolis’ Progressively accelerating degeneration), I used a 35mm digital SLR (remember those? – I still have one!) to photograph the art of every issue: Every cover; all linocuts (“a printmaking technique, a variant of woodcut in which a sheet of linoleum is used for a relief surface“).

I’ve digitally edited my original images, and, have created four blog posts – one illustrating the Yiddish text of Greenberg’s 1923 “In the Crucifix Kingdom (In malkhus fun tseylem) (Weingrad)”, and three others for each issue of Albatros – thus showing each issue’s art. (For a small and entirely unrelated (!) example of this sort of endeavor, check out my post about Jack Williamson’s novel Darker Than You Think. Originally published in John W. Campbell, Jr.’s, Unknown in December of 1940, the 1948 book version of which includes a great frontispiece illustration by Edd Cartier. It gives you an idea.)

An ironic and frank caveat: I must admit that with the exception of the illustration appearing on the cover of the periodical’s first issue, I’m not at all partial to the style of art displayed in Albatros. Quite the contrary. (You can gain an appreciation of the art I do like, elsewhere throughout this blog!) However, my personal feelings about these works are unimportant in light of their historical significance.

Thus, you can view the first issue here, the second here, and the third here.

Enjoy, contemplate, or be so perplexed as you desire!

Acknowledgement and References

First, I’d like to acknowledge the assistance of Israel Medad “…a Jew, a Zionist, a Revenant in Yesha and as an inquisitive human being” … and long-time resident of Shiloh, Samaria, Israel. You can gain many other insights into the poetry, thoughts, and life of Uri Tzvi Greenberg, let alone life Israeli political, literary, and social history, at Israel’s blog, MyRightWord.” (First post in 2004 and still going strong!)

Second, I’d like to thank my translator, Vladimir Yurist, for his fine transcription of the introductory material in the 1978 Jerusalem reprint of Albatros. Vladimir, whose working languages are English, Hebrew, Russian, and Spanish, has over three decades of translation experience in fields such as aerospace, communications training, and medicine. You can avail yourself of his conscientious and attentive work by contacting him at tralenator@gmail.com.

And so:

“Thanks, Vladimir!”

And so, some references…

Uri Zvi Greenberg, at…

… Wikipedia

… YIVO

Some poems by Uri Zvi Greenberg, at…

Save Israel – Articles & Thoughts on the Jewish State

Song of the Great Mind

Creation of the Universe

In a Child’s Ear I Relate

Those Who Live By Their Virtue Will Say

Nation, How Great You Are!

The Legend of Yaacov Raz

A Land Lost

Robbers

Anxiety in My Bones Today

Homesong

With My G-D, The Smith

Like a Woman

The Great Sad One

Jerusalem Surrounded by Walls

Decay of the House of Israel

Not One Truth but Two

Professor Michael Weingrad, at…

Mosaic Magazine

Portland State University – Harold Schnitzer Family Program in Judaic Studies

investigations and fantasies on Jews and Fantasy Literature

The Federalist

Academic Reference Works about Uri Zvi Greenberg

Abramson, Glenda, “The Wound of Memory – Uri Zvi Greenberg’s ‘From the Book of the Wars of the Gentiles’”, Shofar: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies, V 29, N 1, Fall, 2010, pp. 1-21

Hamutal Bar-Yosef, Jewish-Christian Relations in Modern Hebrew and Yiddish Literature: A Preliminary Sketch, Printed in: Jewish-Christian Relations in Modern Hebrew and Yiddish Literatures: A Preliminary Sketch, The Centre for Jewish-Christian Relations, Wesley House, Cambridge, 32 pp. (also in: Themes in Jewish-Christian Relations, edited by Edward Kessler and Melanid J. Wright, Orchard Academic: Cambridge England 2005, pp. 109-150)

Elhanan, Elazar, “The Long Poem As a Site of Blasphemy, Obscenity, and Friendship in the Works of Peretz Markish and Uri Tsevi Greenberg”, Dibur Literary Journal, Issue 4, Spring, 2017, pp. 53-74

Galili, Zeev, Uri Zvi Greenberg – The Poet who Predicted the Holocaust (אורי צבי גרינברג – המשורר שחזה את השואה), at Logic in Madness (Zeev Galili’s online column (היגיון בשיגעון -הטור המקוון של זאב גלילי))

Lipsker, Avidov, Round, Column and Mirror – Gothic Symbolism in the Late Poetry of Uri Zvi Greenberg, Reprinted in the Book “Red Song Blue Song: Seven Essays on the Poetry of Uri Zvi Greenberg – – and Two on Elsa Lasker Schiller”, Ramat Gan: Bar Ilan University / Mossad Bialik, Jerusalem, Israel, 2010

Medad, Israel, On Uri Tzvi Greenberg and Jesus Affinity, at MyRightWord

Neuberger, Karin – Between Judaism and the West – The Making of a Modern Jewish Poet in Uri Zvi Greenberg’s “Memoirs (from the Book of Wanderings)”, Polin – Studies in Polish Jewry, Volume Twenty-Four – Jews and Their Neighbours in Eastern Europe since 1750, The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, Portland, Or., 2012, pp. 151-169.

Neuberger, Karin, “Uri Zvi Greenger’s Farewell to Europe”, Yearbook for European Jewish Literature Studies – 2015, 26 pp.

Stahl, Neta, “Uri Zvi Before the Cross”: The Figure of Jesus in the Poetry of Uri Zvi Greenberg”, Religion and Literature, V 40, N 3, Autumn, 2008, pp. 49-80

Weingrad, Michael, An Unknown Yiddish Masterpiece That Anticipated the Holocaust – Written in 1923, “In the Crucifix Kingdom” depicts Europe as a Jewish wasteland. Why has no one read it?, Mosaic.com,

April 15, 2015

Winther, Judith, “Uri Zvi Grinberg: The Politics of the Avant-Garde – The Hebrew-Zionist Revolution – 1924-1929”, Nordisk judaistik – Scandinavian Jewish Studies, V 17, N 1-2, pp. 24-60, 1996

Winther, Judith, “Tradition and Revolution in Search for Roots in Uri Zvi Grinberg’s Albatros”, Nordisk judaistik – Scandinavian Jewish Studies, V 18, N 1-2, pp. 130-158, 1997

Ydebo, Mette, “En begavet solist er trådt af” [“A Gifted Soloist has Passed”] – Judith Winther 1933-2018 – Obituary, Nordisk judaistik – Scandinavian Jewish Studies, V 29, N 2, pp. 61-63