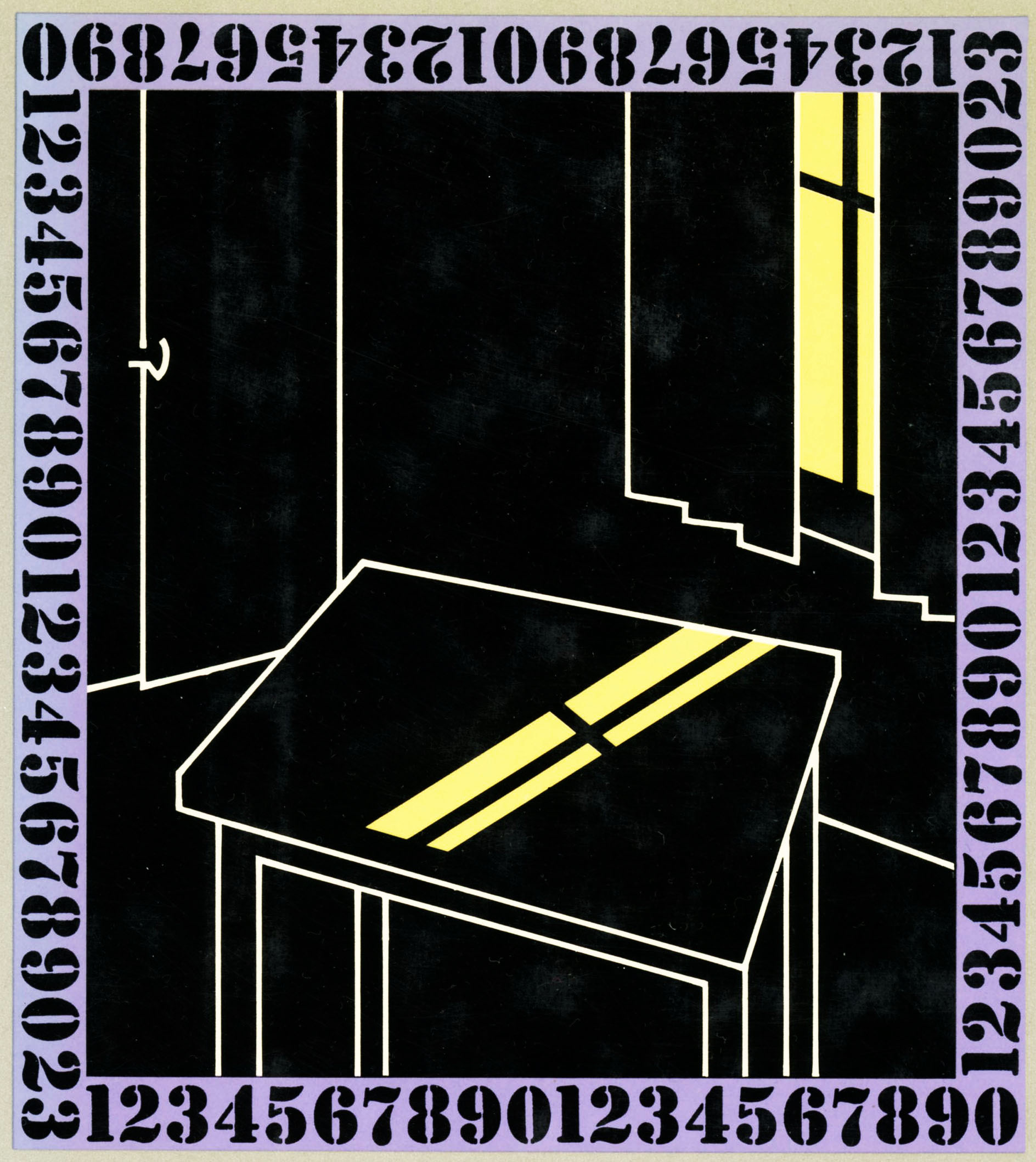

This post, which first appeared in early 2018, has been updated to include Michiko Kakutani’s New York Times July 17, 1992 book review of Things Not Seen. While the “initial” version of the post included the review as a scan, this revision includes the review as full text, followed by a close-up of Raoul Colon’s cover art.

I’ve also (October, 2019) updated the post to include a brief excerpt from the story “Last Shift at The Mine”.

Scroll down just a little…

Contents

Contents

Afghanistan

The Sisters of Desire

Personal Testimony

Sole Custody

A Morning in the Late Cretaceous Period

Last Shift at the Mine

Rescue the Perishing

Legacy

Things Not Seen

________________________________________

Books of The Times

A Thousand Tiny Heartbreaks

By MICHIKO KAKUTANI

Things Not Seen

And Other Stories

By Lynna Williams

213 pages. Little, Brown & Company.

$18.95.

The New York Times

July 17, 1992

The characters in these fine new stories by Lynna Williams are outsiders, people excluded from the safe, warm circle of familial affection.

In “The Sisters of Desire,” a young woman named Chris is recovering from a nervous breakdown. Chris takes a job baby-sitting for an 11-year-old girl named Rachel, who proposes that they form a fan club for her stepfather, Tom. It’s not long before Chris realizes that she has actually fallen in love with Tom, that she wants to replace his wife and take her place beside him as Rachel’s mother. As the impossibility of this fantasy sinks in, Chris sees again “how separate she was, and would always be, from them, through history and circumstance, through all the things she felt but could not say.”

It’s a feeling shared by Ellen Whitmore, a preacher’s daughter who narrates two stories in this volume (“Personal Testimony” and “Rescue the Perishing”). At the age of 9, Ellen learned that she was adopted, and this knowledge warps her subsequent relationship with her father. On one hand, she wants to hurt and embarrass him by ghostwriting phony testimonies for the other children at Bible camp; on the other, she tries to earn back his love by trying to introduce an ill-tempered neighbor, who had supposedly been a Nazi, to Christ.

Looking at her father, she thinks, “I was sure that what I wanted most in the world was for him to love me back, not in the ‘Ellen is my daughter and I have to prove it’ way that was familiar to us both by then, but in the old way, when he looked for me in any room he went into.”

Ms. Williams’s other characters also ostensibly belong to families, but they, too, suffer from feelings of exclusion and alienation. In the title story, a woman named Jenny begins to recover memories of being abused as a child, and these memories, accelerated by therapy, begin to contaminate her marriage. She grows nervous, paranoid and defensive. Her husband, David, soon catches her sense of peril; he begins to distance himself from her and question his own impulses toward their daughter. He tells Jenny he wants “this to be over”; he wants “things to be the way they were.” “What if I’m O.K.,” she responds, “and things still aren’t the same? What if they never are?” In relating such stories, Ms. Williams demonstrates an uncanny ability to write scenes that effectively dramatize her characters’ emotional dilemmas without ever seeming stagey or didactic. Emily, the heroine of “A Morning in the Late Cretaceous Period,” realizes, while wandering through a dinosaur exhibit at the local museum, that memories of her former husband have come between her and her new husband, Tom. “She stops speaking to him halfway through the Triassic period,” Ms. Williams writes, “feigning desperate interest in the museum dioramas of earth 225 million years before.” Moments later, “they enter the Cretaceous period,” she writes. “All around them, the known world is splitting into separate continents, and Emily pushes ahead, until she’s standing alone somewhere on the edge of North America.” She feels stranded and alone, and when she gives Tom a quick, desperate shove she feels “she has moved her marriage toward extinction with an act she can’t explain and can’t take back.”

Anna, the heroine of “Sole Custody,” who lost her child, Katie, to cancer several years ago, experiences a similar epiphanic moment, when she peers in a window of the house belonging to her ex-husband, Jay. Everything she sees inside – pictures of Katie, along with furniture, knickknacks and toys that attest to Jay’s new life with his new wife and new baby – makes her realize how much she has lost, how much she remains in thrall to the past.

Cancer, unemployment and divorce – these sad, ordinary facts of life, rather than the melodramatic sort mentioned on the evening news (“drunk drivers, or snipers at the mall, or boulders pushed at cars from freeway overpasses”) – are the ones that haunt Ms. Williams’s characters. In many cases, the mere fear or premonition of such “things not seen” is enough to drive these people to the brink of emotional despair. By dwelling on bad memories or intimations of some unnamed future disaster, they court misunderstanding and bad luck.

In “Afghanistan,” a man named Hopkins tries to decipher a note left by his wife: “Have gone to Afghanistan. Tess at Scotts’ overnight. Food in fridge.” The second half of the note is clear and accurate: his daughter, Tess, is indeed at a neighbor’s house for the evening, and there is a casserole with stuffed pasta shells in the refrigerator. The first sentence is more perplexing: since his wife is a linguist, Hopkins tells himself, Afghanistan must be a kind of code for something else. After reading a newspaper story with a headline that says, “Afghan Left Feels Betrayed by Russians,” he decides that “Afghanistan” must symbolize “betrayal” to his wife, although he’s unsure whether she means her betrayal of him, or his betrayal of her.

In each of these stories, Ms. Williams writes with quiet assurance, delineating her characters’ psyches with the same authority she brings to her descriptions of their day-to-day routines. The writing is limpid, almost translucent, allowing the reader almost complete access to these people’s inner lives. One is left with both an appreciation of the resilience of love and an understanding of its frightening limitations: its failure in the face of illness, grief and existential fear.

____________________

– Lynna Williams –

____________________

____________________

We’ve known for months we couldn’t stay unless Mark could find permanent work.

We’d talk about it sometimes late at night,

but then it would be another day and we’d be doing anything we could to stay.

I could write a book about that – about all the things we never thought could happen to us.

Like going on welfare this winter, when Mark couldn’t find any work at all for six weeks.

On my going to work at the Traveler’s Motel three days a week, cleaning rooms.

Two and a half years ago, when Mark got laid off again,

we would have fought about my working at any job, much less as a maid.

But not anymore.

I know he’d do it instead if he could.

When I come home on those days, he and Molly make me sit at the table

while they bring me dinner like it’s a hotel.

“Madame, perhaps desires the macaroni?” Mark will say,

and Molly, who’s started to swallow the beginnings of words,

will punch me on the arm with her little fist and say, “Caroni, Dame?”

I am never sorry about anything when they’re carrying on like that.

And as long as Mark is talking, I know we’re all right.

So we’ve been doing whatever we’ve had to – until two weeks ago.

That was when Mr. Peterson told me there’s not enough business at the motel

and they don’t need me anymore.

We’ve been using that money, and whatever we can earn doing odd jobs, to eat,

and drawing out what little savings we have left to pay the utilities.

My parents made the June house payment.

We let them because it looked like there might be a buyer if we could just hang on.

There are some older people up here looking for retirement homes.

But nothing’s happened, and we can’t wait anymore. (“Last Shift at The Mine”, pp. 145-146)