Sometimes, to see the present more clearly, you have to go back to the past.

Case in point, “this” post, created way back on December 6 of 2016 (a “lifetime” in blog history!), showing cover art – by an unknown artist – of Popular Library’s 1965 paperback imprint of Jan Karski’s Story of a Secret State.

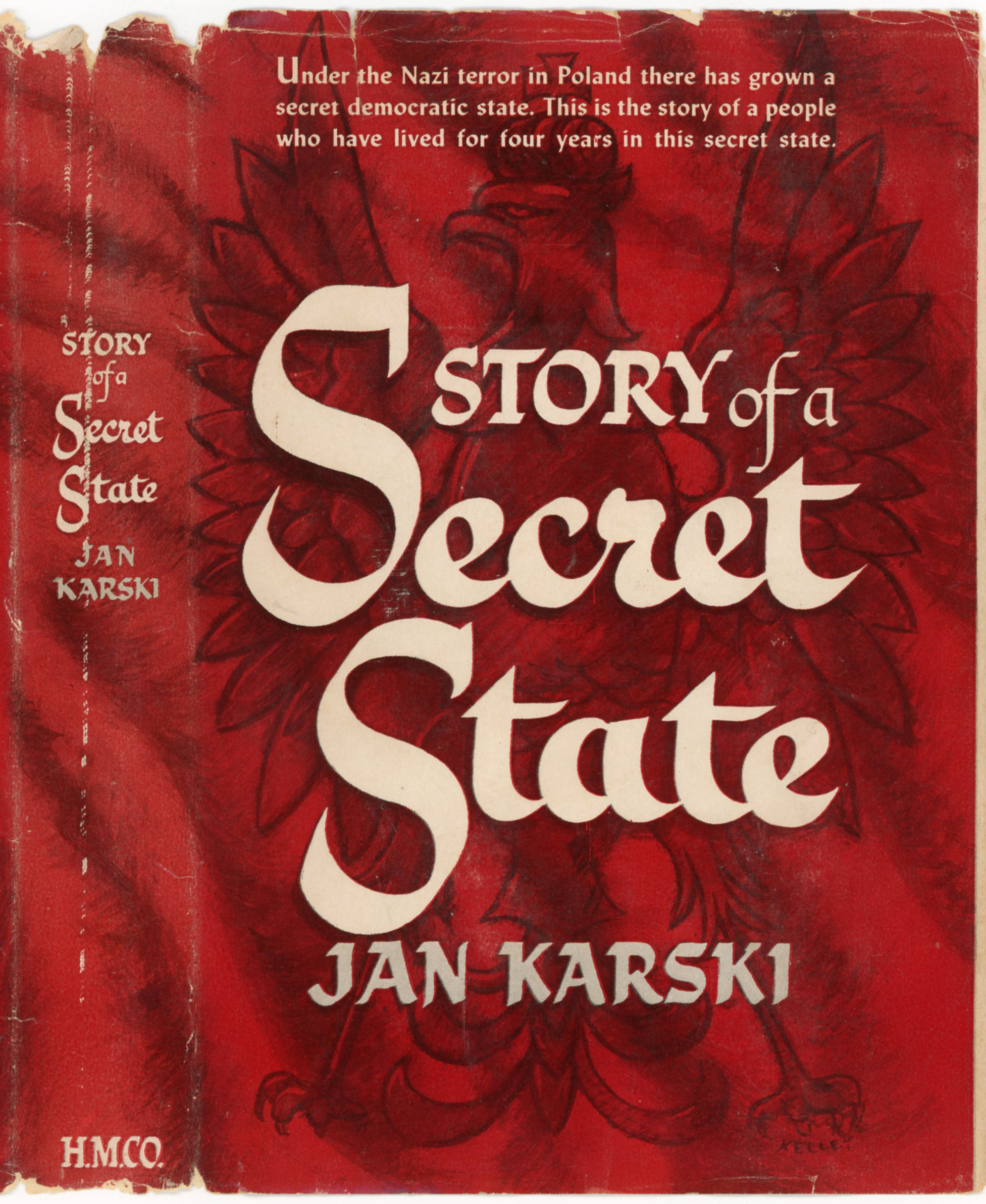

However, it’s only befitting to show the very cover of the first edition of Karaki’s superbly written, riveting, and morally impassioned work. Published by Houghton Mifflin (Boston) in 1944, the front cover displays a stylized white eagle from the National Coat of Arms of Poland…

…while the rear cover shows Blackstone Studios’ portrait of Jan Karski.

________________________________________

…and here is the front cover of Popular Library’s paperback:

We were in a part of Poland neither of us knew well.

We were in uniform, possessed no documents of any kind,

and had no idea of conditions about us.

We were hungry; weakened by the ordeals of the last few weeks;

and in the now heavy downpour had no protection but our threadbare garments.

In the circumstances, there was nothing to do but trust to luck.

Determining to knock at the door of the first dwelling we came upon,

we got up and walked through the wood

until we came to a narrow strip of grassless soil

that was obviously either a path or a road.

After about three hours of trudging through the rain,

we perceived the outlines of a village, and slackened our pace,

approaching it cautiously.

Tiptoeing quietly up to the first cottage,

we found ourselves at a small, typical peasants’ dwelling.

Hesitantly we stood before the door from under which a dim light issued.

As I raised my hand to knock, I felt a tremor of nervousness and apprehension.

I rapped on the door with brusque over-emphasis to allay my dread.

‘Who is it?’ The trembling voice of a peasant reassured me slightly.

‘Come out, please,’ I replied,

attempting to make my voice sound polite but authoritative,

‘it is very important.’

The door opened slowly,

disclosing a gray-headed old peasant with a grizzled beard.

He stood there in his underwear, obviously frightened and cold.

A wave of warm air from the interior made me feel almost faint

with the urge to enter and bask in it.

‘What do you want?’ he asked in a tone of mingled indignation and fear.

I ignored the question.

I decided to try to play boldly on his feelings.

‘Are you or are you not a Pole?’

I demanded sternly. ‘Answer me.’

‘I am a Polish patriot,’

he replied with greater composure and celerity than I had anticipated.

‘Do you love your country?’ I continued undismayed.

‘I do.’

‘Do you believe in God?’

‘Yes, I do.’

The old man evinced considerable impatience at my questions

but no longer seemed terrified – merely curious.

I proceeded to satisfy his curiosity.

‘We are Polish soldiers who have just escaped from the Germans.

We are going to join the army and help them save Poland.

We are not defeated yet. You must help us and give us civilian clothes.

If you refuse and try to turn us over to the Germans, God will punish you.’

He gazed at me quizzically from under his thick eyebrows.

I could not tell if he was amused, impressed, or alarmed.

‘Come inside,’ he said dryly, ‘out of this miserable rain.

I will not turn you over to the Germans.’

But Wait, There’s More!…

…some links pertaining to the life of Jan Karski, at…

… Internet Archive (Jan Karski Papers)

… Online Archive of California (Jan Karski Papers)

… Jan Karski Educational Foundation

December 6, 2016 – 242 hits as of 7/21/22