“And through those plump cities the sad young men back from battle wander

as strangers in a strange land,

talking a grim language of realism which the smug citizenry doesn’t understand,

trying to tell of a tragedy which few enjoy hearing.”

FOREWORD

FOREWORD

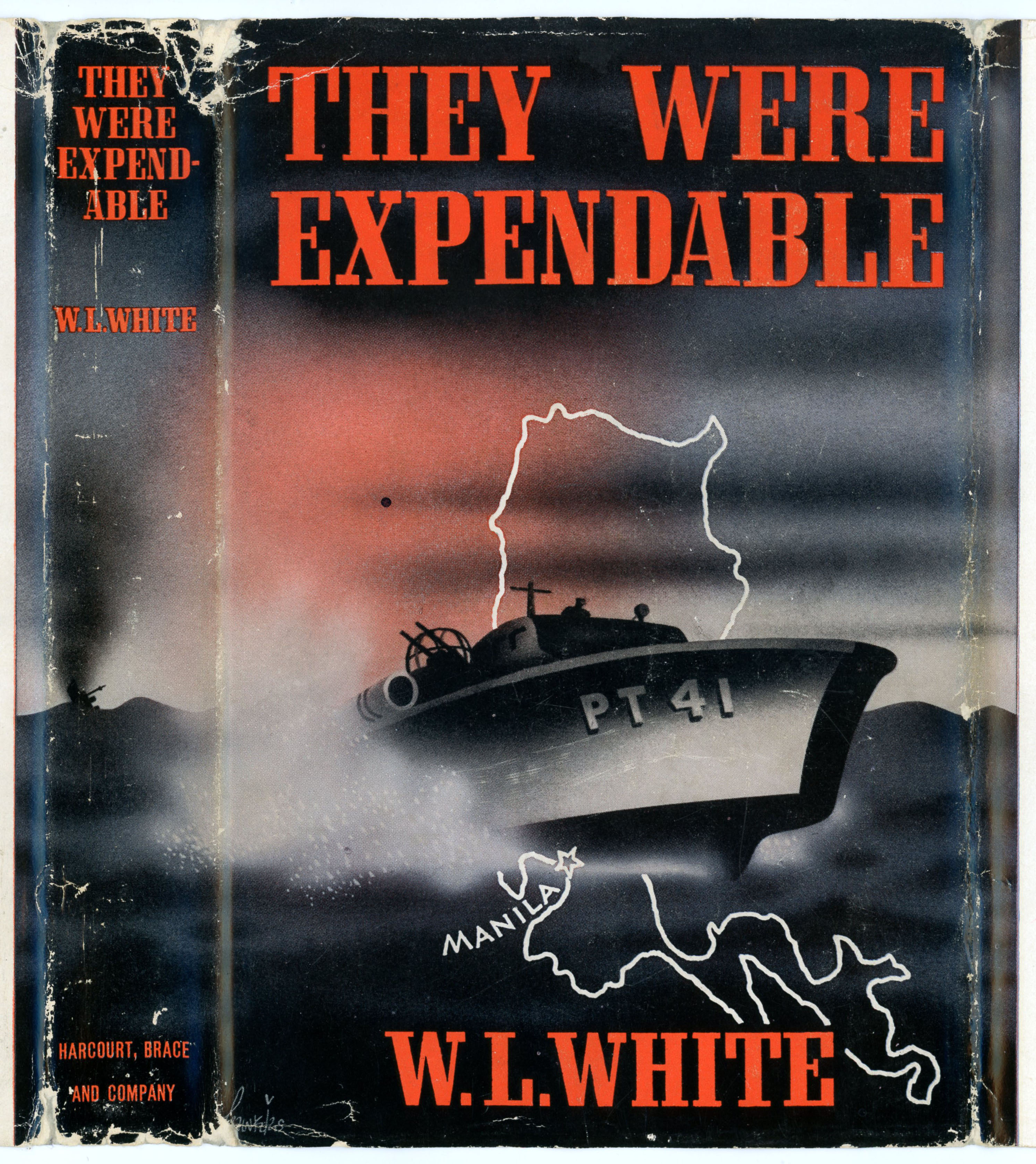

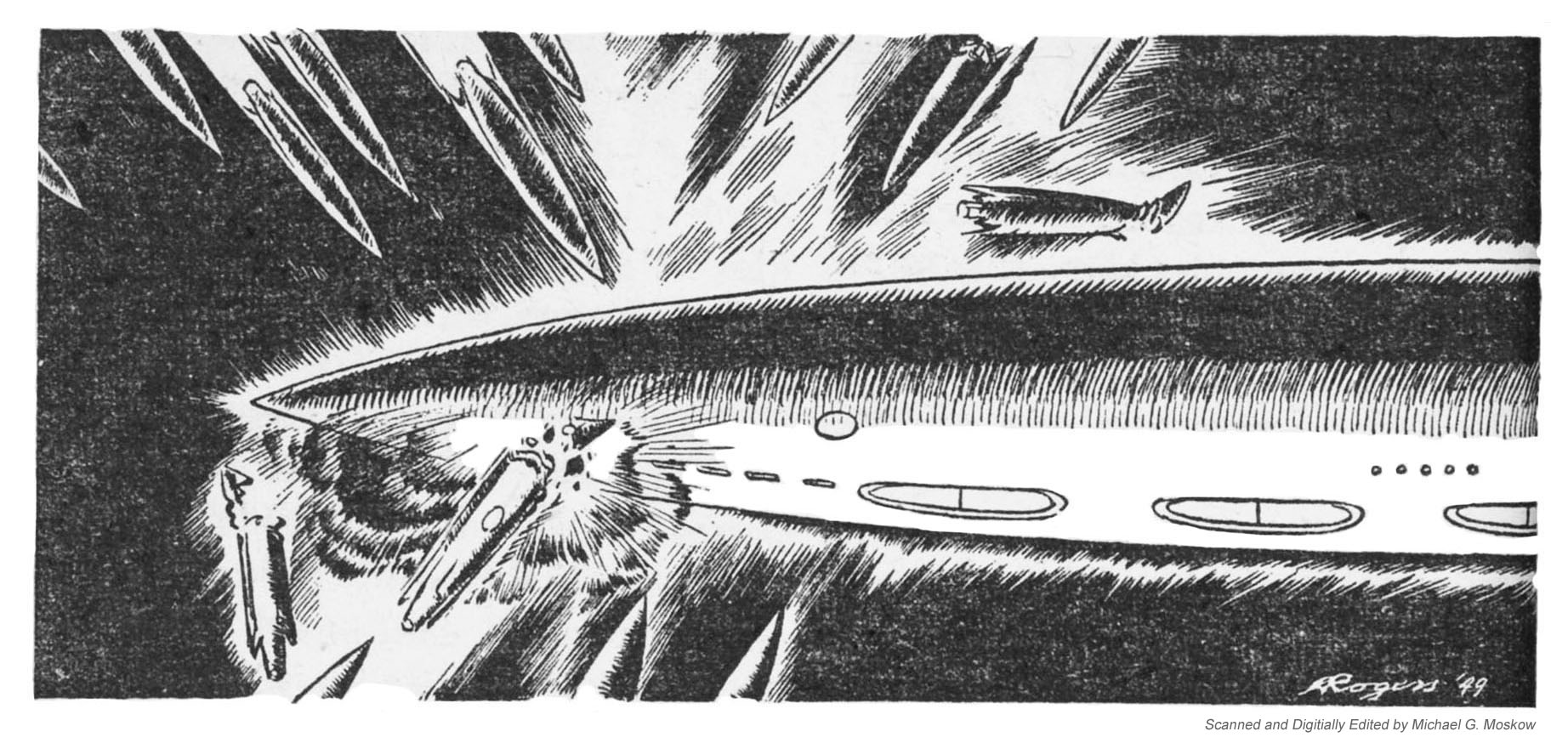

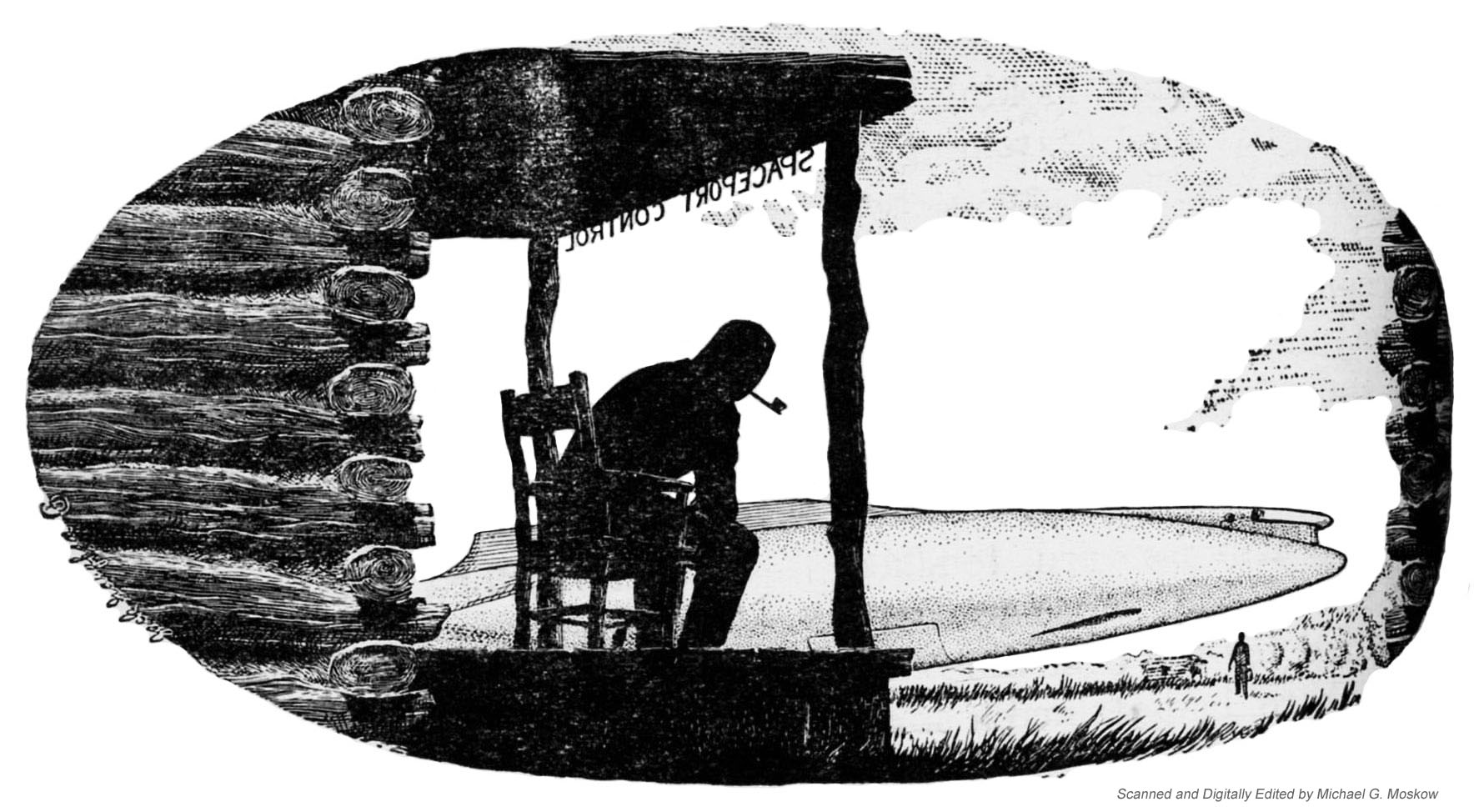

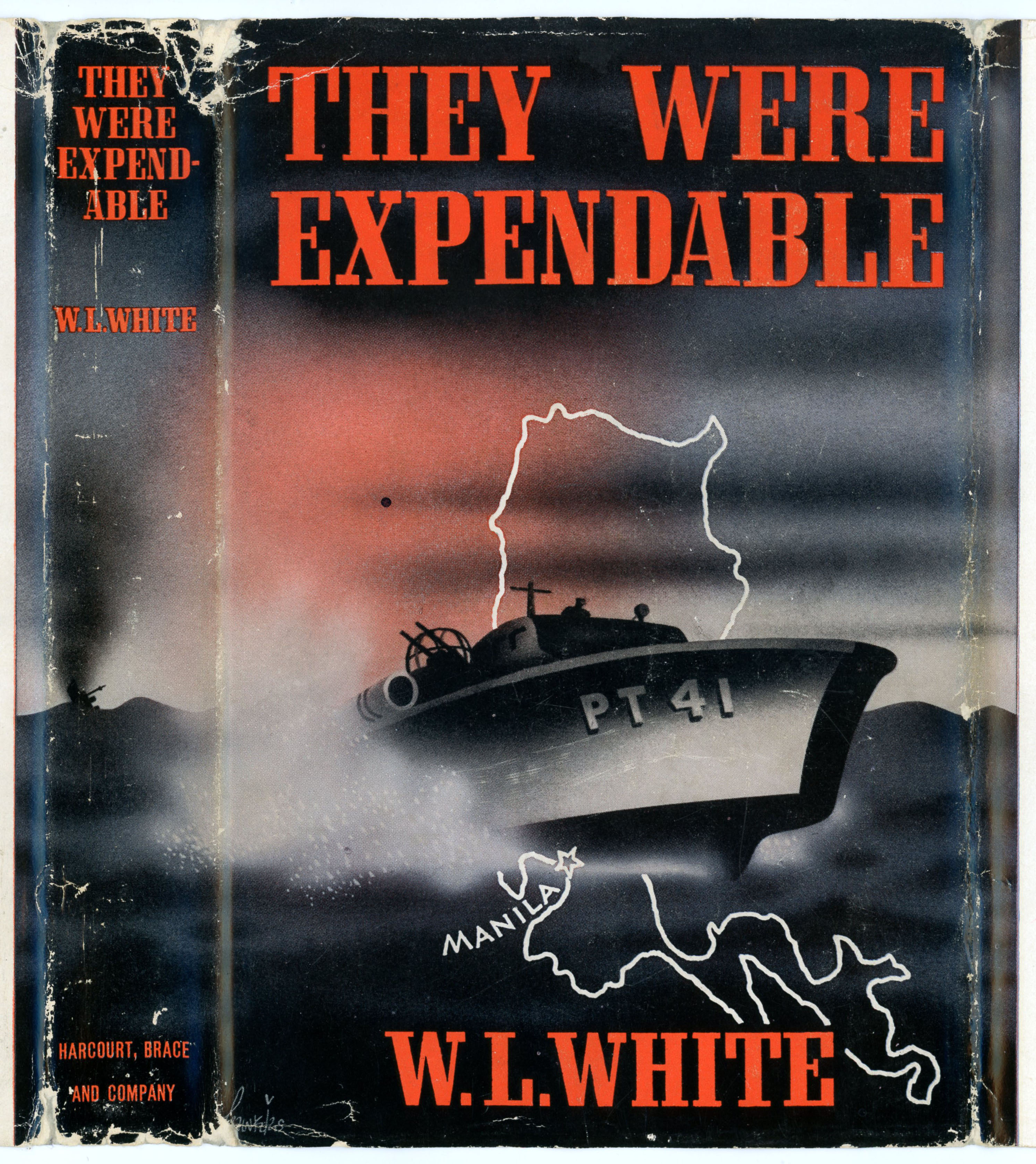

THIS story was told me largely in the officers’ quarters of the Motor Torpedo Boat Station at Melville, Rhode Island, by four young officers of MTB Squadron 3, who were all that was left of the squadron which proudly sailed for the Philippines last summer. A fifth officer, Lieutenant Henry J. Brantingham, has since arrived from Australia.

These men had been singled out from the multitude for return to America because General MacArthur believed that the MTB’s had proved their worth in warfare, and hoped that these officers could bring back to America their actual battle experience, by which trainees could benefit.

Their Squadron Commander, Lieutenant John Bulkeley (now Lieutenant-Commander) of course needs no introduction, as he is already a national hero for his part in bringing MacArthur out of Bataan. But because the navy was then keeping him so busy fulfilling his obligations as a national hero, Bulkeley had to delegate to Lieutenant Robert Boiling Kelly a major part of the task of rounding out the narrative. I think the reader will agree that the choice was wise, for Lieutenant Kelly, in addition to being a brave and competent naval officer, has a sense of narrative and a keen eye for significant detail, two attributes which may never help him in battle but which were of great value to this book. Ensigns Anthony Akers and George E. Cox, Jr., also contributed much vivid detail.

As a result, I found when I had finished that I had not just the adventure story of a single squadron, but in the background the whole tragic panorama of the Philippine campaign – America’s little Dunkirk.

______________________________

We are a democracy, running a war.

If our mistakes are concealed from us, they can never be corrected.

Facts are frequently and properly withheld in a war,

because the enemy would take advantage of our weaknesses if he knew them.

But this story now can safely be told because the sad chapter is ended.

The Japanese know just how inadequate our equipment was,

because they destroyed or captured practically all of it.

I have been wandering in and out of wars since 1939,

and many times before have I seen the sad young men come out of battle –

come with the whistle of flying steel and the rumble of falling walls still in their ears,

come out to the fat, well-fed cities behind the lines,

where the complacent citizens always choose from the newsstands

those papers whose headlines proclaim every skirmish as a magnificent victory.

And through those plump cities the sad young men back from battle wander

as strangers in a strange land,

talking a grim language of realism which the smug citizenry doesn’t understand,

trying to tell of a tragedy which few enjoy hearing.

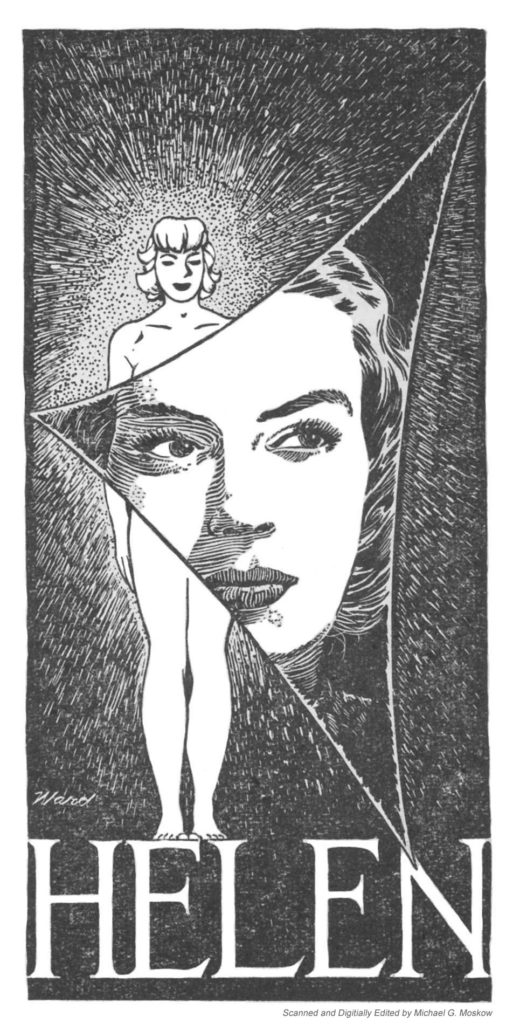

These four sad young men differ from those I have talked to in Europe

only in that they are Americans,

and the tragedy they bear witness to is our own failure,

and the smugness they struggle against is our own complacency.

W.L. WHITE