Originally created in February of 2019 and having appeared at one of my Brother blogs, ThePastPresented, I’ve now updated and modified this post – about the book “Fighter Pilot” – comprised of posthumously published letters written by WW II Army Air Force fighter pilot 1 Lt. Levitt Clinton Beck, Jr. – to appear “here”, at WordsEnvisioned.

Though the book by definition pertains to aviation and military history, by virtue of being a “book” per se (well, that’s what it is!) and bearing two examples of Lt. Beck’s own art, its historical significance and unusual nature merit that its author not be forgotten.

Enjoy!

________________________________________

“On the other hand,

if I don’t make it,

everything I have written will be here for anyone to read,

and I feel it will make a better ending to my life than just to be

“missing in action.”

“When you read all this I shall be right there looking over your shoulder.”

________________________________________

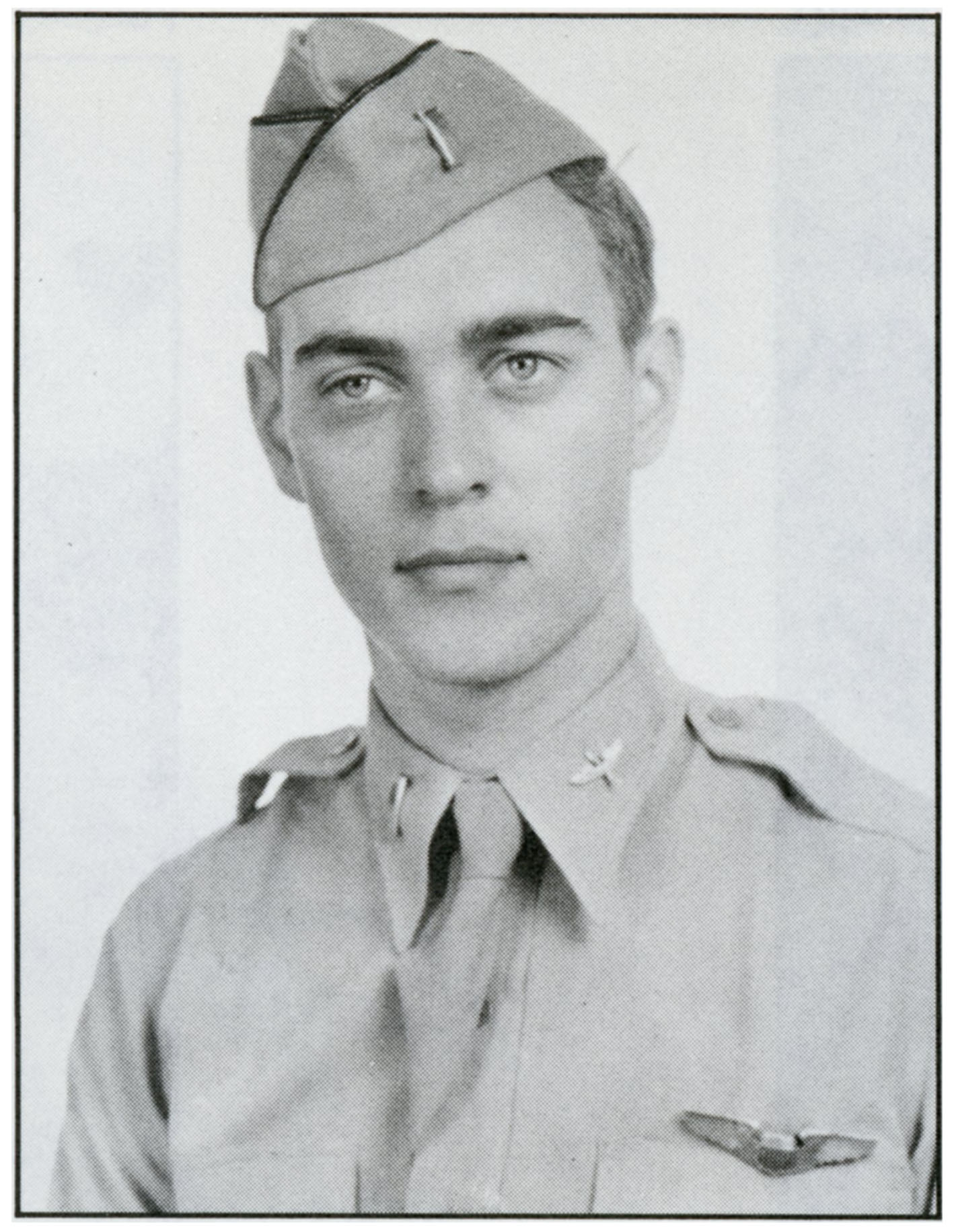

This photographic portrait of Levitt Clinton Beck, Jr. is from the National Archives’ photo collection “Photographic Prints of Air Cadets and Officers, Air Crew, and Notables in the History of Aviation – NARA RG 18-PU”. Though I don’t know the Advanced Flying School from which Lt. Beck graduated and received his commission, the large pin that he’s wearing, bearing the abbreviation “43-B”, indicates that he received his wings in February of 1943.

No words are needed to convey his pride and determination.

________________________________________

Military literature from all eras is replete with autobiographical accounts of the wartime experiences and postwar reminiscences of its participants. Such narratives, whether published during the immediacy of a conflict, or afterwards – years, and not uncommonly decades later – are typically based upon combinations of official documents, letters, diaries, photographs, illustrations, and above all, human memory, however fickle, imperfect, or uncertain the latter may be. The commonality of most such accounts, regardless of the era; regardless of the war; even regardless of the identity of the soldier and the nation for which he fought; is that the participant of the past, would become the chronicler, creator, and literary craftsman within the present, for the future.

Among the vast number of books and monographs presenting the story of a soldier’s wartime experiences, is another kind of literature, bearing its own nature and origin. That is, stories about the lives and military experiences of servicemen who never returned from war, created by family members – typically parents – sometimes by former comrades – as living memorials that exists in words, and grant indirect testimony of and witness for those who can no longer speak.

A striking example of this genre of military literature is the book Fighter Pilot., created and published in 1946 by Levitt Clinton and Verne Ethel (Tryon) Beck, Sr., of Huntington Park, California. The book is a posthumous autobiography of their son, First Lieutenant Levitt Clinton Beck Jr., who served as a fighter pilot in the 514th Fighter Squadron of the 406th Fighter Group, of the 9th Air Force. Centrally based upon the thoughts, musings, retrospectives, and then-undelivered “letters” penned by their son, and including transcripts of correspondence several photographs, Fighter Pilot is historically fascinating, detailed, and from a “human” vantage point, a literary work that is best termed reflective – for the reader, and, by Beck, the writer.

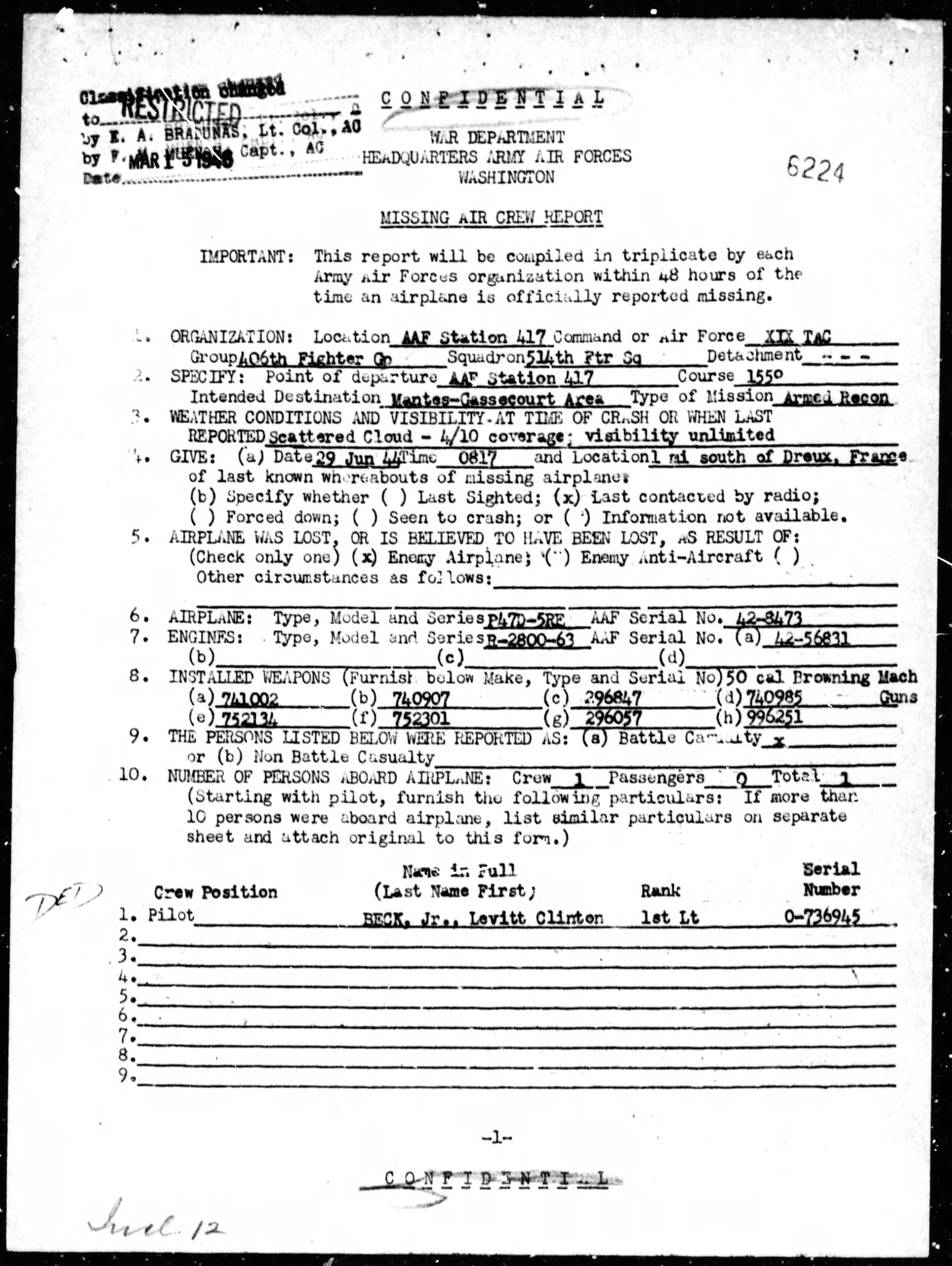

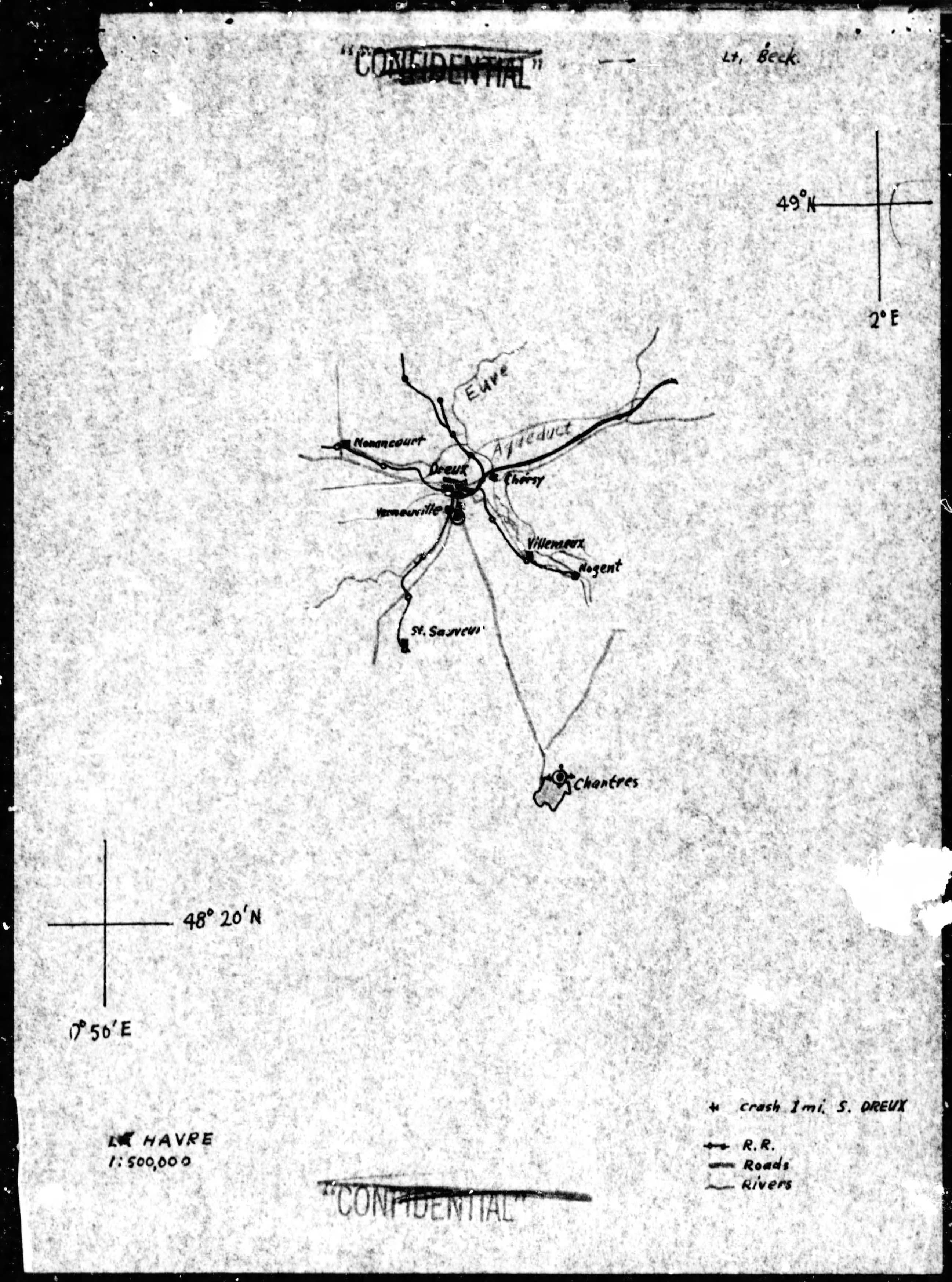

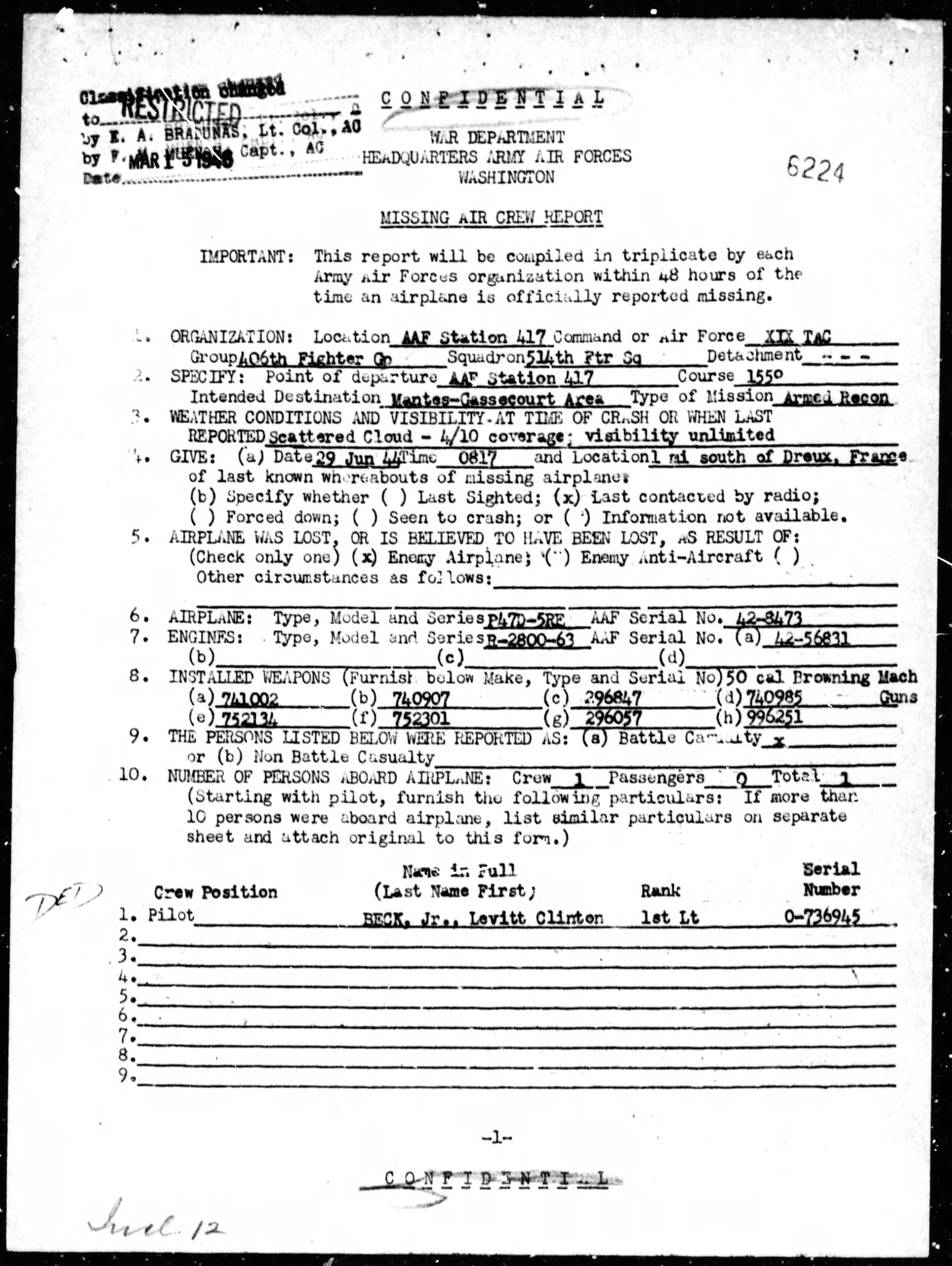

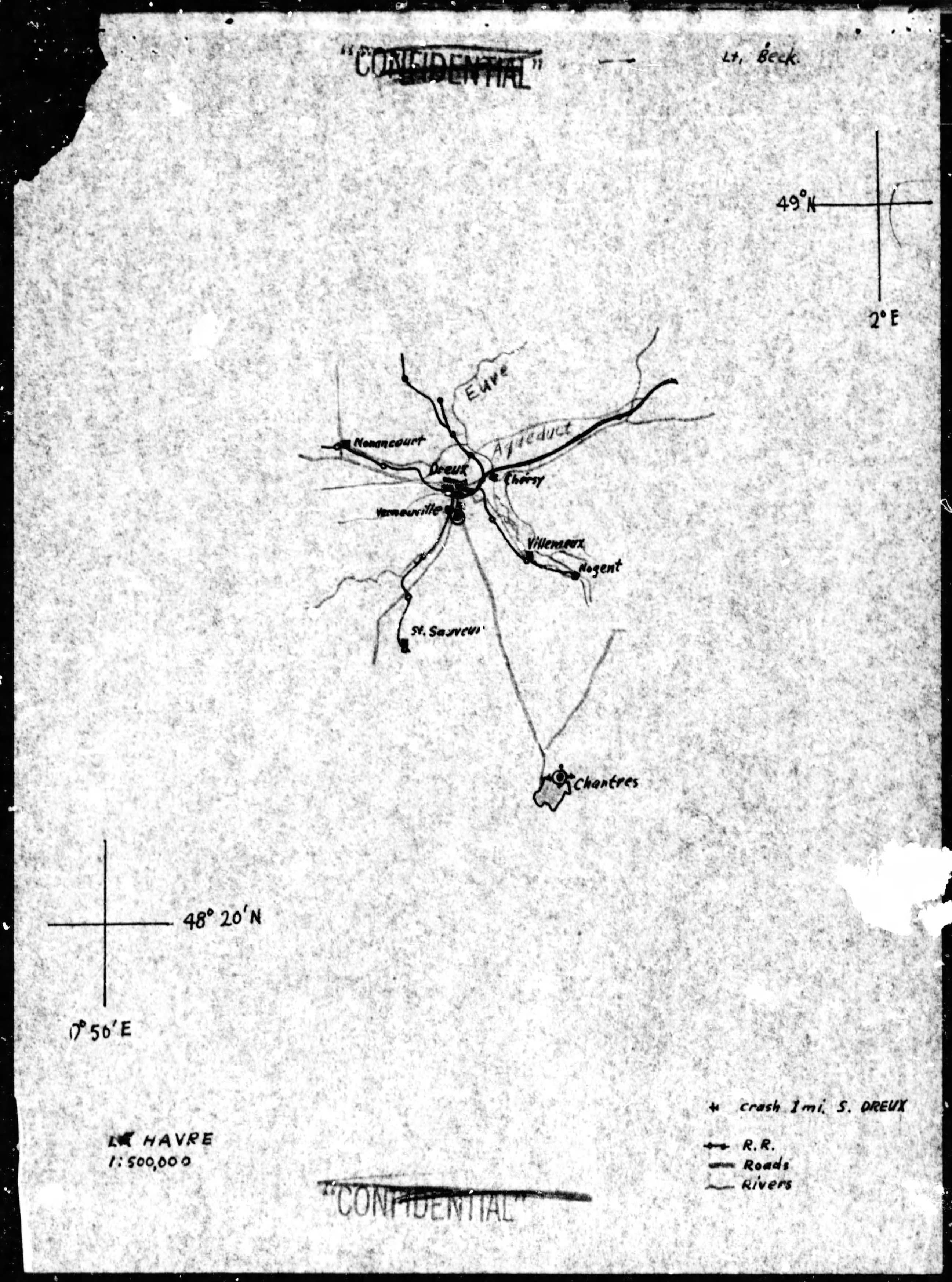

Shot down during a brief encounter with FW-190s of JG 2 or JG 27 on June 29, 1944, Beck crash-landed his damaged Thunderbolt (Bloom’s Tomb; P-47D 42-8473) south of Dreux, France, near Havelu. His loss is covered in MACR 6224.

Taken to Les Branloires by Roland Larson, he was given civilian clothes by a Mr. Pelletier, and then taken to the town of Anet, where he remained for three weeks, hidden by Madame Paulette Mesnard in a room above her restaurant, the Cafe de la Mairie (on Rue Diane de Poitiers). There, while safely hidden (Fighter Pilot reveals that Madam Mesnard insisted that Lt. Beck remain there until Anet’s liberation by Allied troops…) he would compose the writings that would eventually become Fighter Pilot.

Three weeks later, Lt. Beck was taken to the home of Mr. Rene Farcy, in Les Vieilles Ventes.

One week further, Beck was picked up by a certain “Jean-Jacques” and the latter’s female companion, “Madame Orsini”. Ostensibly a member of the Underground, Jean-Jaques was actually Jacques Desoubrie, a double agent who worked for the Gestapo. Desoubrie took Lt. Beck to a hotel in Paris, on Boulevard St. Michel.

The next day, the Lieutenant was arrested by the Gestapo and taken to the prison of Fresnes.

From there, in accordance with German policy (as of the Summer of 1944) towards Allied aviators captured while garbed in civilian clothing and without military identification (dog-tags), and, in association with resistance networks in Belgium, France, and the Netherlands, Beck was one of 168 captured Allied aviators sent to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp.

A very detailed account of the mens’ experiences at Buchenwald can be found at the Wkikipedia biography of RNZAF pilot Squadron Leader Phillip John Lamason, DFC & Bar, who became the senior officer of the group. As quoted, “Upon arrival, Lamason, as ranking officer, demanded an interview with the camp commandant, Hermann Pister, which he was granted. He insisted that the airmen be treated as POWs under the Geneva Conventions and be sent to a POW camp. The commandant agreed that their arrival at Buchenwald was a “mistake” but they remained there anyway. The airmen were given the same poor treatment and beatings as the other inmates. For the first three weeks at Buchenwald, the prisoners were totally shaved, denied shoes and forced to sleep outside without shelter in one of Buchenwald’s sub-camps, known as ‘Little Camp’. Little Camp was a quarantine section of Buchenwald where the prisoners received the least food and harshest treatment.”

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

“As Buchenwald was a forced labor camp, the German authorities had intended to put the 168 airmen to work as slave-labor in the nearby armament factories. Consequently, Lamason was ordered by an SS officer to instruct the airmen to work, or he would be immediately executed by firing squad. Lamason refused to give the order and informed the officer that they were soldiers and could not and would not participate in war production. After a tense stand-off, during which time Lamason thought he would be shot, the SS officer eventually backed down.

“Most airmen doubted they would ever get out of Buchenwald because their documents were stamped with the acronym “DIKAL” (Darf in kein anderes Lager), or “not to be transferred to another camp”. At great risk, Lamason and Burney secretly smuggled a note through a trusted Russian prisoner, who worked at the nearby Nohra airfield, to the German Luftwaffe of their captivity at the camp. The message requested in part, that an officer pass the information to Berlin, and for the Luftwaffe to intercede on behalf of the airmen. Lamason understood that the Luftwaffe would be sympathetic to their predicament, as they would not want their captured men treated in the same way; he also knew that the Luftwaffe had the political connections to get the airmen transferred to a POW camp.”

Eventually, the men were transferred out of Buchenwald, with 156 going to Stalag Luft III (Sagan). Ten others were were transported from the camp over a period of several weeks.

Two of the 168 did not survive: They were Lt. Beck, and, Flying Officer Philip Derek Hemmens (serial 152583), a bomb aimer in No. 49 Squadron, Royal Air Force. Hemmens’ Lancaster Mk III, ND533, EA * M, piloted by F/O Bryan Esmond Bell, was shot down during a mission to Etampes on the night of June 9-10. Ironically, Hemmens was the only crew member to actually escape from the falling plane. His fellow crew members died in the crash of EA * M.

Lt. Beck, weakened from an earlier bout of illness from the conditions in the concentration camp, died from a combination of pneumonia and pleurisy while isolated in the camp’s “hospital”, on the evening of September 29-30, 1944.

He has no grave. His name is commemorated on the Tablets of the Missing at the Luxembourg American Cemetery.

Similarly, the name of F/O Hemmens, who died on October 18, is commemorated at the Runnymede Memorial.

Well, there is at least some justice in this world, even if that justice is not speedy: Jacques Desoubrie, whose infiltratation of two French Resistance groups eventuated in the arrest of at least 150 Resistants, fled to Germany after France’s liberation. He was, “…arrested after being denounced by his ex-mistress, and executed by firing squad as a collaborationist on 20 December 1949 in the fort of Montrouge, in Arcueil (near Paris).”

____________________

For one so young at the time (Beck was 24), the overlapping combination of seriousness, introspection, contemplation, and literary skill (and, some levity) in his writing are immediately apparent.

A central and animating factor in Beck’s words was the realization of the danger of his predicament, and the possibility that – however remote, at the time; for reasons unknown, at the time – he might not return. He was realistic about this. Whether this feeling arose from a premonition, or objective contemplation of the danger of his situation, either or both motivations spurred him to record thoughts and create letters for two eventualities:

His return, and the creation of a permanent record of his experiences, perhaps for the sake of reminiscing; perhaps for eventual publication.

His failure to return, and a document by which he could be remembered by his parents and friends. (He was an only son.)

As he recorded:

“The idea has been growing within me these last few days that I should like to take all these experiences and others I have had, and have my book, “Fighter Pilot,” published after the war is over. There is the thought, too that “Lady Luck” may not be able to ride all the way with me. So, while I have a few days to wait for the French Underground to complete their plans for my escape back to England, I see no reason why I shouldn’t write every day, all that I can, so that just in case my luck has run out, you will know what has happened to your wandering son.”

______________________________

I obtained a copy of Fighter Pilot some decades ago. The book was republished in Honolulu by “Book Vompay LLC” in 2008, with the book’s Worldcat entry stating that, “This edition is a revised and corrected version of the original, which was first published in 1946.” As of this moment – late 2022 – two original copies are available from two eBay sellers, at $20 and $40, while Kissinger Legacy Reprints has republished the book for a selling price of $40 to $50.

Some extracts from the book’s text, as well as some images, are shown below. These will give you a feel for the book’s literary and historical flavor.

______________________________

The book’s dust jacket bears an image of a bubbletop Thunderbolt, almost certainly sketched by Beck himself. Though the canopy frame bears a kill marking denoting a destroyed German plane (see account below), this aerial victory was not confirmed: USAF Credits for the Destruction of Enemy Aircraft, World II, contains no entry for this event.

____________________

____________________

A poem by Beck, composed at the age of twenty.

I SEE IT NOW

(Written in 1940)

By L.C. Beck, Jr.

I WATCHED the day turn into nite,

Creeping shadows reached the sky;

Birds flew to their nests,

Still singing as they went;

All mankind lay quiet at rest,

As though to heaven sent.

Quiet ne’er before was like this –

Even wind hung softly about the trees,

As is afraid of waking birds,

Sleeping in their nests;

‘Twas like another world to me,

And I found myself wishing –

Wishing it were true.

I’ve suffered – and have hated it,

But in my mind a thought was born,

Making a new path for me –

On which I now find my way.

I see it now –

While I suffer here

I must not question of it;

It is the way of life –

Too much happiness would spoil me;

I’d grow too fond of life on earth

And the after life I seek

Would not be so sweet -.

We must have our troubles here;

Our hearts torn by loss,

Our hands made bloody by war,

Our future left unknown.

Once again the time has come

When day and night do meet, –

But all are going in ways apart

And but touch here in their passing;

I’m glad that God mas made it so

For it thrills me to my very soul

To see so bright a luster of the day

Meet the sweet sereneness of the night.

____________________

The book’s simple and unadorned cover.

____________________

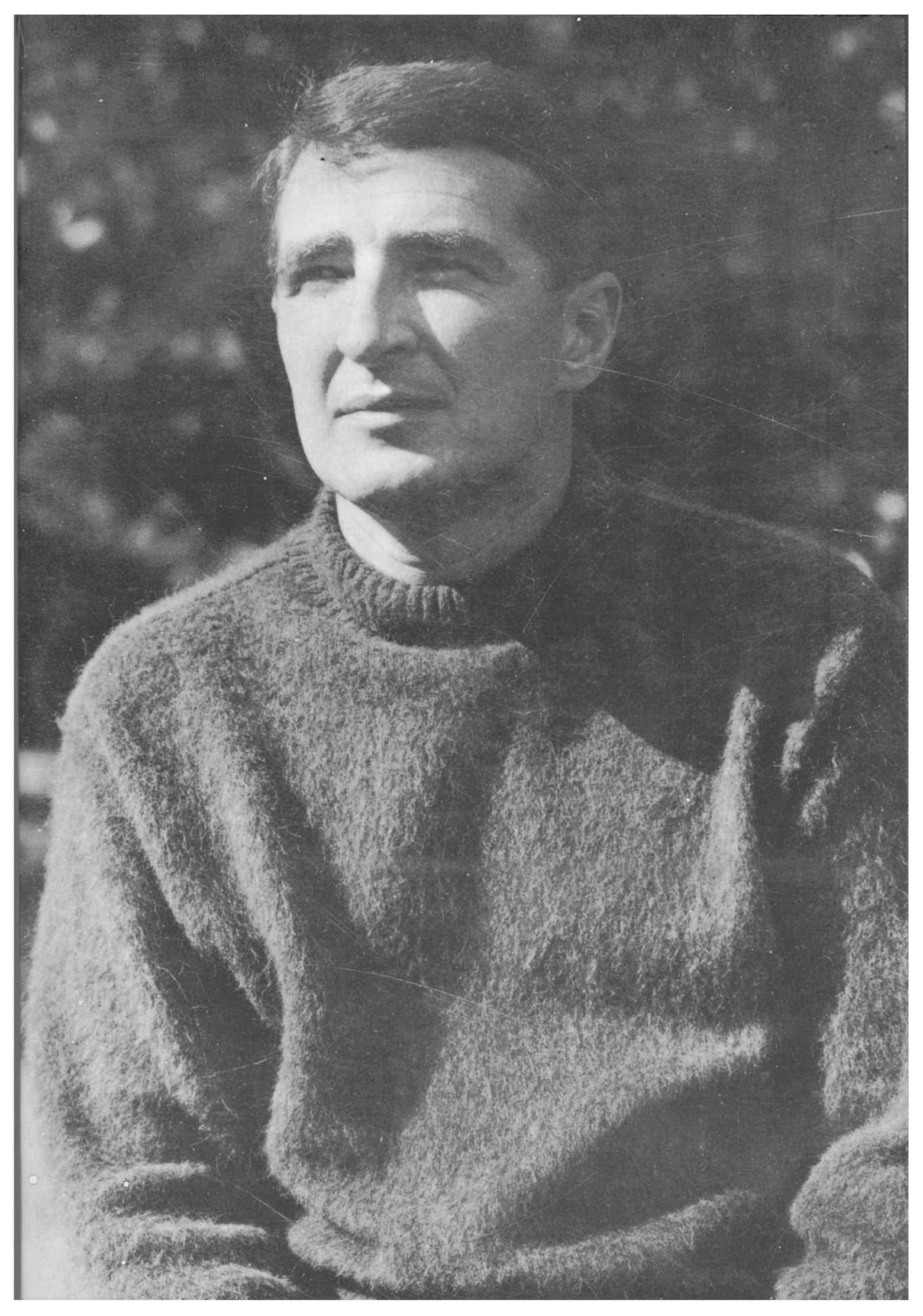

1 Lt. Levitt Clinton Beck, Jr., in an undated image taken in the United States.

____________________

____________________

Pilot, propeller, and power. Given Beck’s rolled-up sleeves and the intense sunlight, this picture was probably taken somewhere in the southeastern United States. Another clue: 406th Fighter Group P-47s did not have white engine cowlings.

____________________

____________________

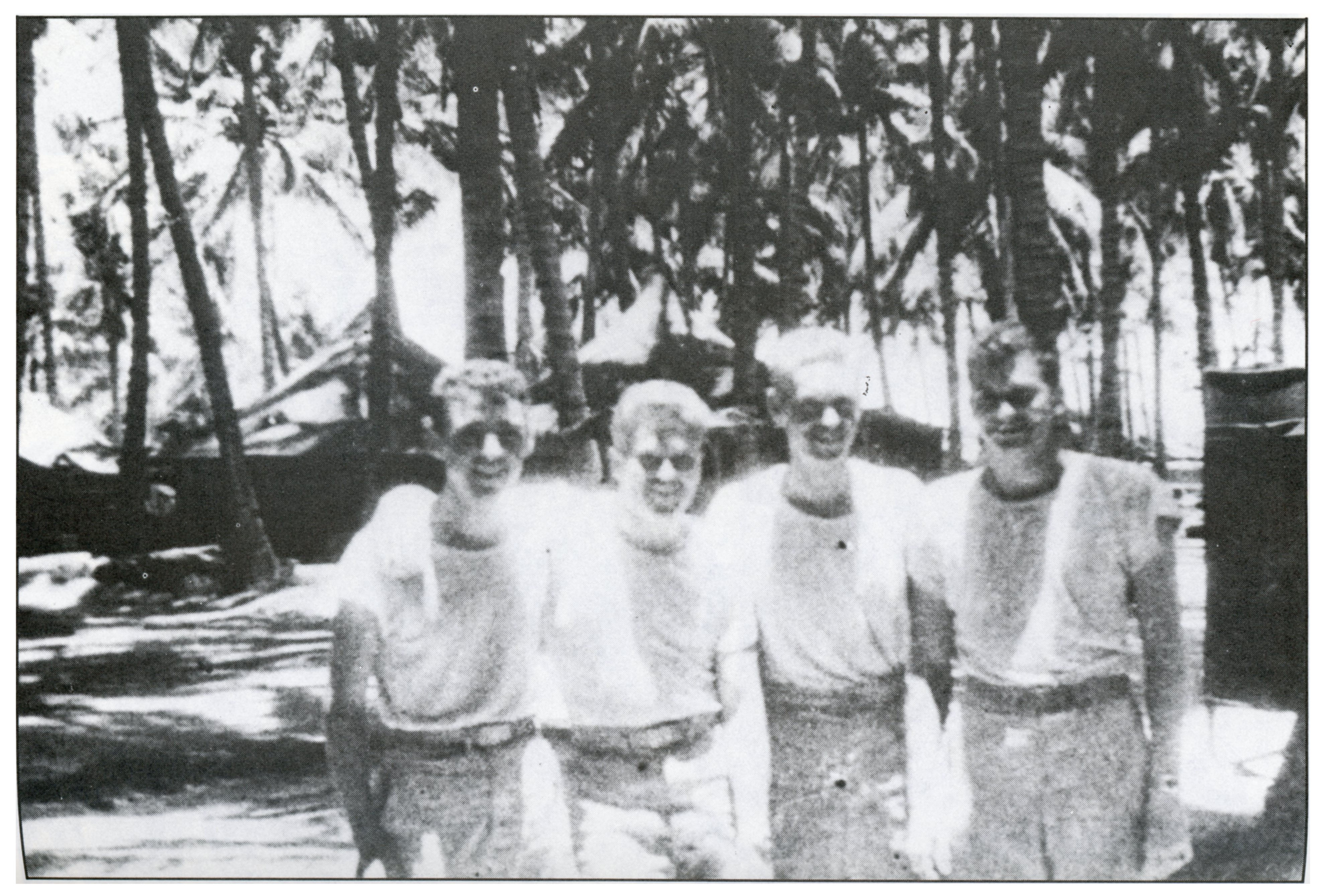

Dated March 8, 1944, this picture is captioned “Officer’s Party, AAF”.

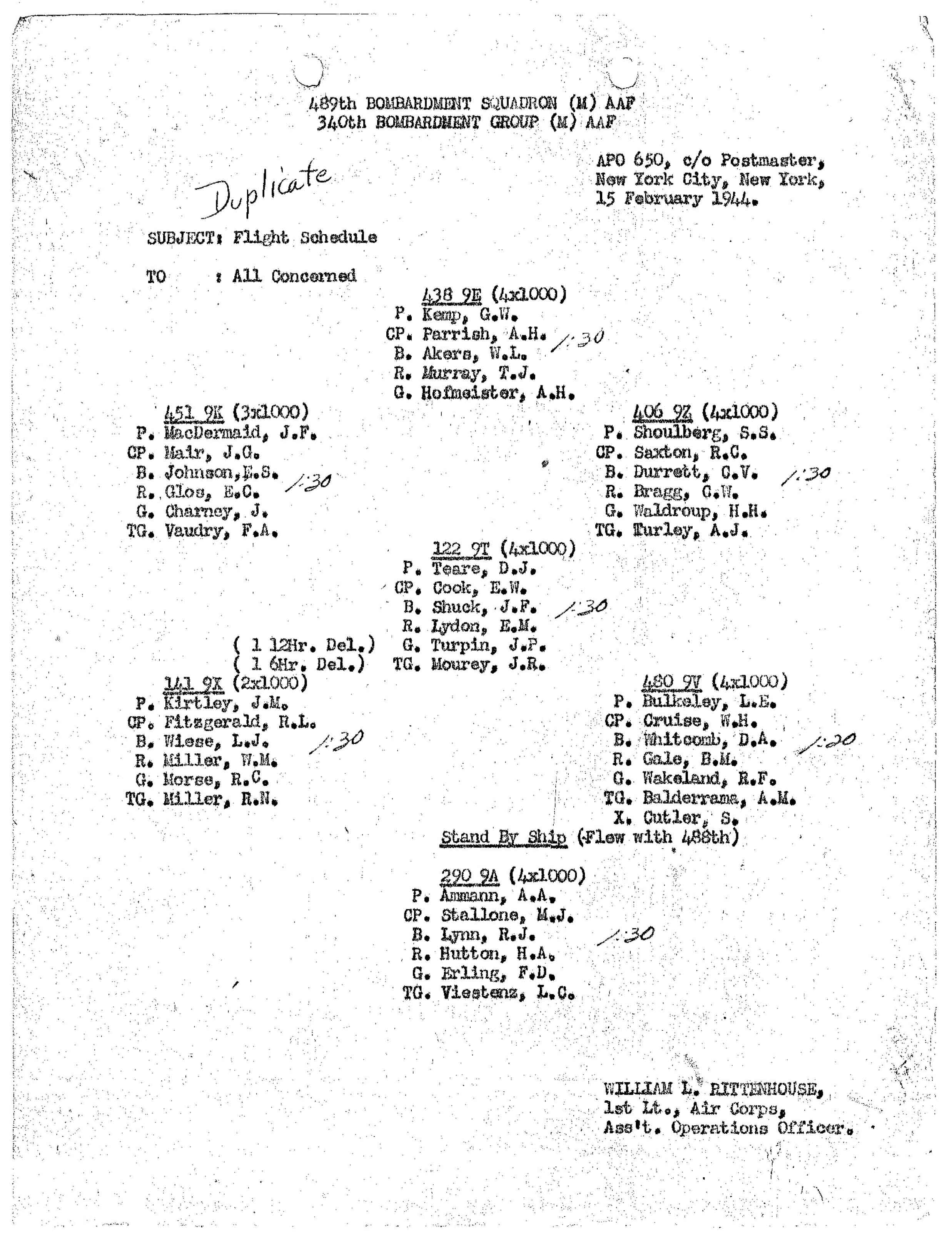

Fighter Pilot lists the names of the men in the photo. They are (left to right):

Front Row

Billington, James Lynn 2 Lt. (0-810463) – Queens County, N.Y.

KIA June 24, 1944, MACR 6346, P-47D 43-25270

Dugan, Bernard F. 2 Lt. (0-811868) – Montgomery County, Pa.

KNB April 15, 1944 (No MACR)

Born 8/16/19

Arlington National Cemetery; Buried 7/19/48

Beck, Levitt Clinton, Jr., Lt.

Middle Row

Long, Bryce E. Lt. (0-811938) – Edmond, Ok. (Survived war)

Van Etten, Chester Lumley Major (0-663442) Los Angeles, Ca. (Survived war)

Gaudet, Edward R. 2 Lt. (0-686738) – Middlesex County, Ma.

KIA June 29, 1944, MACR 6225, P-47D 42-8682

“Atherton”

Benson, Marion Arnold 2 Lt. (0-806035) – Des Moines County, Ia.

KIA June 17, 1944, MACR 6635, P-47D 42-8493

Rear Row

Cramer, Bryant Lewis 1 Lt. ( 0-810479) – Chatham County, Ga.

KIA August 7, 1944, MACR 7405, P-47D 42-75193

Cara Montrief (grand-daughter) According to Fighter Pilot, Cramer’s daughter was born three weeks after her father was shot down.

Dorsey III, Isham “Ike” Jenkins – Opelika, Al. (Survived war)

David “Whitt” Dorsey (brother)

Note that Major Van Etten is wearing RAF or RCAF wings.

____________________

Lieutenant Beck’s loss in combat is covered in Missing Air Crew Report 6224. However, Beck’s own account of his last mission, written while he was in hiding at Anet and providing the “other side” of the Missing Air Crew Report, appears in Fighter Pilot. His final radio call, “Eddie, I think I may have to bail out,” – probably to 2 Lt. Edward R. Gaudet – was heard and reported as “My airplane is hit. I think I’ll have to bail out,” by 1 Lt. Bryant L. Cramer, who himself was shot down and killed less than two months later.

As for Lt. Gaudet, he was shot down and killed during the very same aerial engagement as Lt. Beck, while flying P-47D 42-8682. His loss is covered in MACR 6225.

Images of MACR 6224, and Lt. Beck’s story as recorded in Fighter Pilot, follow below:

CHAPTER TWO

My First “Victory”

WE WERE TO fly the “early one” that morning of June 29th. We dashed down in the murky dawn, that only England can boast about, for breakfast and briefing. Both very satisfying, we took off and headed for our target, just a few miles south-west of Paris, along the Seine river. My flight carried no bombs, as we were to be top cover for the squadron on their bomb run. It was a group (three squadrons) mission.

Just before we reached the first target, a bridge, the flak opened up and we did some evasive action to go around it. None of it came very close to my flight, but we were not giving them very much of a target to shoot at, I guess. The clouds made it rather hard to keep the others down below in sight, so I dropped down to about 12,000 feet. We lost the rest of the squadron for a while and then I spotted them to the west, being shot at. I started over there with my flight and as we neared the others, someone in my flight called:

“Break, Beck, flak. Break left!”

I did, and then, Eddie, I believe, said: “It’s a 190.”

I turned 180 degrees and saw the 190 in the middle of three 47s — Cramer, Eddie and Unger. I gave it full boost and started back after the little devil. He looked very small among the Thunderbolts and I had no trouble recognizing him as a 190. He was breaking up and then I think he saw me coming after him as he turned around and we were then going at each other head on. For a brief second I thought of breaking up into a position where I could drop on his tail, but he was the first Jerry I’d ever seen and I wasn’t going to let him live that long if I could help it.

I knew, however, that his chances of shooting me, at head on, would be just as good but I was a little too eager and mad to give a damn. I squeezed the trigger and I think the first round hit him because I saw strikes on his cowl, wing roots and canopy all the way in. I guess I’d have flown right through him, but he broke up a little to the left and I raked his belly at very close range. I thought to myself:

“Becky, there’s your first victory.”

Just to make sure, though, I turned with him and started down but I didn’t seem to be going very fast. I rammed the throttle with the palm of my hand but was rather astonished to feel it already up against the stop. I flipped on the water switch but that didn’t seem to do any good either. I looked down at my instruments and then it was very clear. My engine had been shot out. I felt a little panicky at first but settled down and started “checking things.”

Nothing I did seemed to have any effect, so I called:

“Eddie, I think I may have to bail out.“

Oil started licking back over the cockpit. Here we go again, I thought. Just like Cherbourg. She is even worse this time, I guess. The damned engine was just turning over and that was about all. I knew I could never make the channel but I was still trying, I guess, because I was messing around with the throttle and everything I could get my hands on … 6000 feet now.

I still had my eye on my “victory”, though. He was going down in a spiral to the left, smoking very badly. Wham! Something hit me in the back and threw me forward. I didn’t need to look to know what it was. I broke to the left pulling streamers off everything and there he was. A sleek little 190 sitting on my tail – gray and shiny, spitting out flames of death up at me. It wasn’t a very pretty sight, I must say — looking down his cannons — I knew then that I was no longer fighting to get the ship running again. I was fighting for my life!!

I was pretty scared for an instant, but it seems that just when I get that feeling inside and almost think I’m a coward, something snaps. It did, and I was once again the mad fighting American I had been, with an engine. I forgot for the time being that my engine was dead, I guess, because I watched him flash past and then jerked my kite around to the right to a point I knew he would be. I hadn’t looked out the front of the canopy for some time and now as I did, all I saw was the reflection in the glass, covered with oil, of my gun-sight. I cursed and pulled the trigger, shooting in the dark, but at least I felt better. I kicked the ship sideways to have a look out of the side and there was Jerry — just a hundred yards up front. I swung the nose around to about the right position, I thought, and fired. I don’t know whether I hit him or not, but he seemed in pretty much of a hurry to get the hell away.

I pressed the “mike” button and said:

“I’m bailing out.” But all I heard was deathly silence. I knew then that my radio had been blown to bits by the Jerry on my tail.

I thought that I’d better jump at about 4000 feet, so I undid my safety belt and just then my ship shuddered and I heard terrific explosions all around me. I looked out of the only clear space left in the canopy, and saw more flak than I’d ever dreamed possible in one small area. I couldn’t see which way to break so I just went to the right, because the ship did, I guess. I knew then that to bail out would mean sure capture and I still had just a wee bit of hope left for my chances of getting away. I decided to stick with the ship and try a trick that “Benny” and I had talked about one night before he was killed.

I opened the canopy a crack so I could see the ground and when I did, I saw the longest clear stretch of land I think I ever saw in France. It was just about the right distance away, I thought, for me to make my dive to the deck and then scoot over there, at tree top level, and belly in.

I remembered that I had taken my safety belt off, so I started trying to put it on and still keep my eye on Jerry at the same time — also fly the ship— without an engine. Some fun, and if you want to try your ability at being versatile, it is a good trick.

I got under Jerry without his seeing me, I guess, and then down among the trees; I had to keep a keen eye out of the cockpit, so I gave up the idea of buckling my belt again, and decided that I would stretch my luck a bit more, by doing the impossible. I really had no choice, but to hell with the belt. Here comes Jerry again. I had about 275 MPH, so I felt pretty “safe”, you might say. I would wait until he got in range, then break and throw off his aim and then belly in. It was very simple, when you happen to be the luckiest guy in the whole air force. I put one hand on the instrument panel and waited until I got slowed down a bit. I eased her down slowly and was just about ready to touch the ground when I realized that I had not put my flaps down and my stalling speed would be much too fast. I pulled up, but just before I did, I felt my prop hit the ground. I pushed the flap handle down and then watched the grass go by on either side. It seemed as though I’d buzzed half way across France by now and I must be running out of field. I kicked the ship sideways and looked. The trees were still quite some distance ahead, so I eased the old girl down and then I was sliding. I put my “stick hand” on the panel, too, and just braced myself and waited. It shook me around quite a bit, but as I had ridden quite a few rough roller coasters without a safety belt, I was doing pretty well without one now at 100 MPH or so in a 7 1/2-ton hunk of metal. Just before the last few feet, the ship turned to the right and threw me crashing into the left side of the cockpit. It was then that I realized that my back and ribs were already sore from the shock I’d received from the 190’s cannon.

Flames were licking up over the cowling of my ship and I had no more than enough time to get out. I knew I wouldn’t have to destroy my ship. I jumped out, parachute and all, and again hit on my left side, on the wing. I was pretty sore around that part of me by now, also quite excited and too mad to care much.

A few yards from the ship I stopped long enough to take off all the equipment strapped to me. I considered taking the escape kit out of my ‘chute pack, but there wasn’t time.

When you are 100 miles inside enemy territory, naturally one has the feeling that every bush hides a German. I was quite inexperienced in ground fighting, so I didn’t look forward to shooting it out with the Germans with my .45 pistol.

Thoughts were running through my mind about just what to do and how, all during those first five or ten seconds. I even thought about hiding my ‘chute as we had been instructed in a lecture, but I looked back at my airplane and almost laughed.

______________________________

At approximately 0815 on 29 June, I was flying the wing of Yellow Flight Leader, Lt. Beck, at 13,500 ft. on a heading of 260o over Dreux. The flight was jumped all too effectively at this time by four FW-190s, who came out of the clouds directly over us. Lt. Beck and I broke left, bit one of the 190s got hits on Beck’s airplane before I could get it off his tail. His engine was smoking rather badly, and as I followed the enemy aircraft down in a dive, attempting to close into effective range, I heard Lt. Beck call on the radio and say, “My airplane is hit. I think I’ll have to bail out.” I can not say for sure whether he made the jump successfully or not, nor am I positive he did jump. It is quite probable, however, that he did jump, and successfully. A pilot from the 513th Squadron, flying below us at the time of the encounter, reported seeing an unidentified, black fighter dive into the ground, and saw a chute open up above it. The Focke-Wulfs were silver.

Missing Air Crew Report 6224…

Here’s NARA’s digital version of the original Luftgaukommando Report (“Meldung über den Abschuss eines US-Amerikanisch Flugzeuges” – Report about the downing of an American airplane) covering the loss of Lt. Beck and his Thunderbolt: J-1582. Note that though Lt. Beck was shot down on June 28, 1944, this document was actually compiled only a little over four months later: November 2, 1944. Lt. Beck had died two months before.

Also from Here’s a list (list number 28, to be specific) of four of the Allied warplanes shot down in France on June 27-28, 1944. Data about losses appears as black typed text, while identification numbers of pertinent Luftgaukommando Reports appears in bright red. The Luftgaukommando Report numbers are KE 9108, KE 9065, J 1582 (Lt. Beck’s plane), and KE 9064. Note that Lt. Beck, name then unknown, is reported as being a “flüchtig”: close translation “fugitive”.

I’ve been unable to correlate KE 9108 to any aircraft, but KE 9064 definitely pertains to Lancaster III JB664 (ZN * N) of No. 106 Squadron RAF, piloted by P/O Norman Wilson Easby, and KE 9065 covers Lancaster I LL974 (ZN * F), piloted by F/Sgt. Ernest Clive Fox. Of the seven men in the crew of each aircraft – both of No. 106 Squadron RAF – there were, sadly, no survivors.

As described in W.R. Chorley’s Bomber Command Losses, Volume 5:

JB664: T/o 2255 Metheringham similarly targeted. [To attack rail facilities at Vitry-le-Francois.] Crashed 2 km E of Bransles (Seine-et-Marne), 16 km SE of Nemours. All [crew] were buried in Bransles Communal Cemetery.

LL974: T/o 2255 Metheringham to attack rail facilities at Vity-le-Francois. Shot down by a night-fighter, crashing at Thibie (Marne), 11 km WSW from the centre of Chalons-sur-Marne. All were buried locally, since when their remains have been brought to Dieppe for interment in the Canadian War Cemetery.

Though KE Report numbers – covering British Commonwealth Aircraft losses – appear in NARA’s master list of Luftgaukommando Reports, I don’t know if (well, I don’t believe) they’re actually held at NARA.

______________________________

Here’s a postcard view of the main street of Rue Diane de Poitiers in Anet. Lt. Beck lived on the third floor of the building on the right, in the room with the window directly below the small “X”.

Below, is a 2018 Oogle Street view of Rue Diane de Poitiers, which (well, to the best degree possible!) replicates the orientation and perspective of the above 1940s postcard image. Akin to the postcard, the view is oriented south-southeast. The window of Lt. Beck’s hiding place is visible directly beneath the leftmost of the two television antennae.

The location of Madame Mesnard’s restaurant was (in 2018) occupied by a branch of the Banque Populaire, while the business to the right (_____ Centrale“) was at the time the Pressing Diane Anet laundary service.

Below is another 2018 Oogle view of 16 – 18 Rue Diane de Poitiers.

Below is another 2018 Oogle view of 16 – 18 Rue Diane de Poitiers.

______________________________

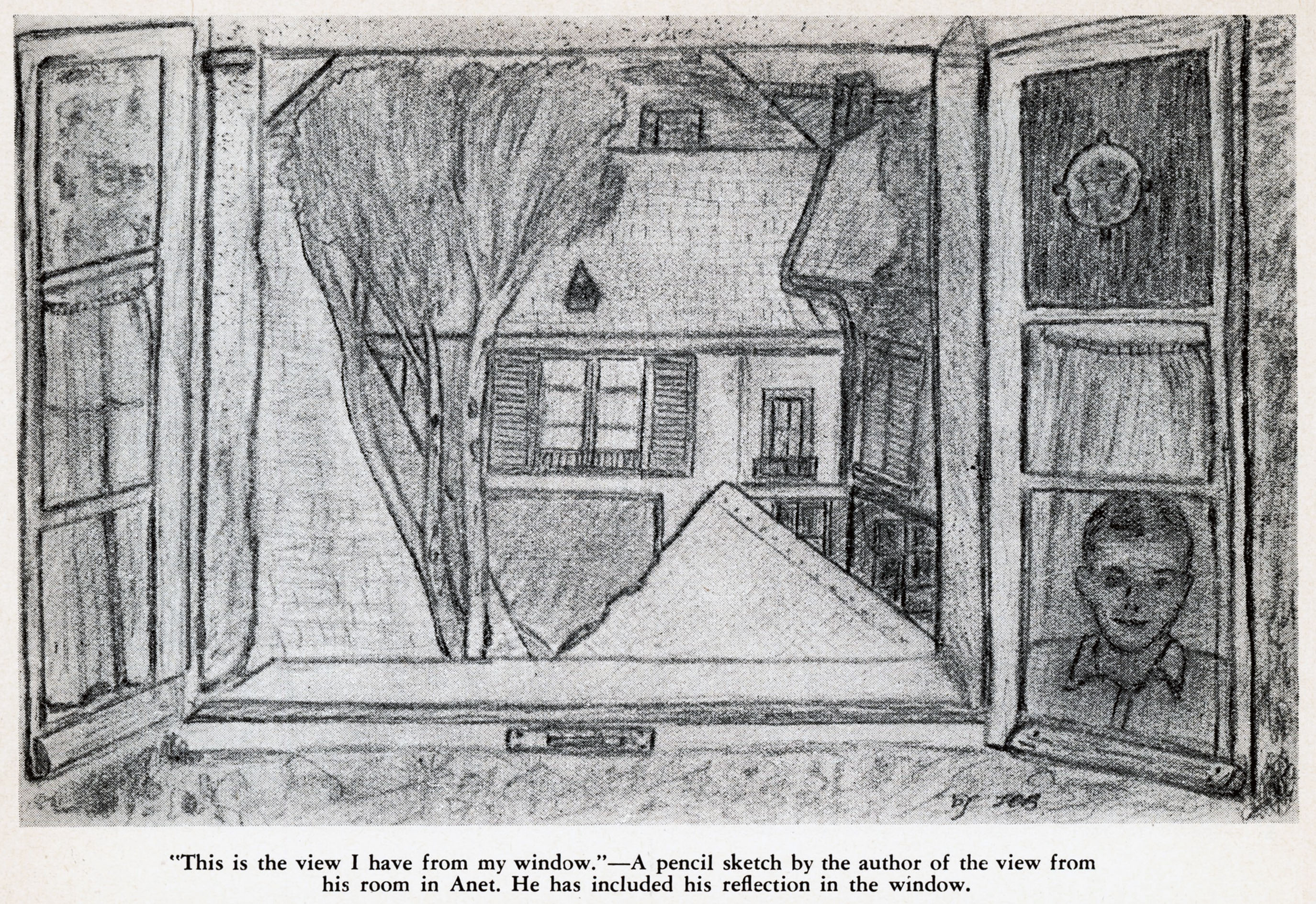

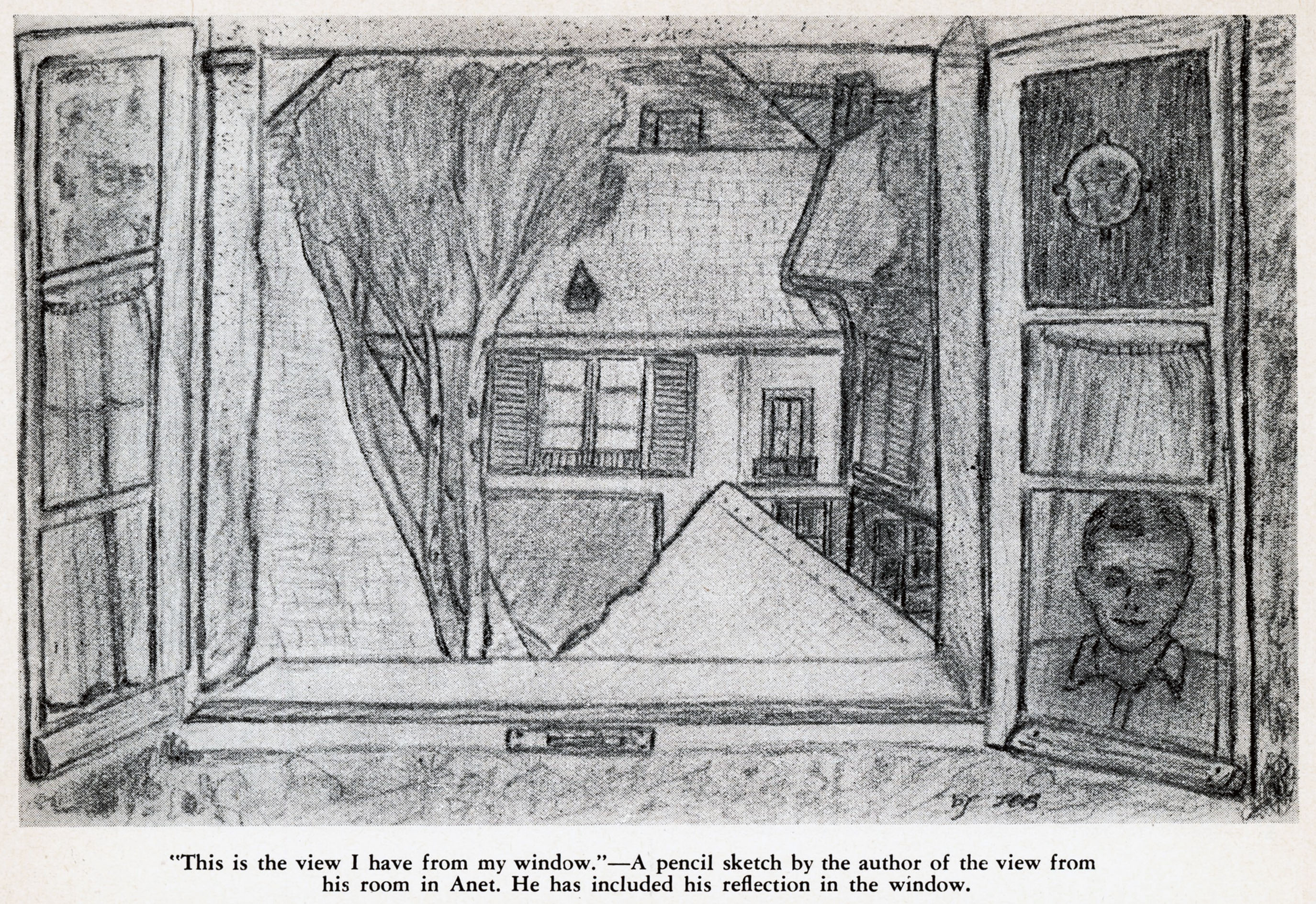

Here’s s a very different view of Rue Diane de Poitiers: The drawing, sketched by Lt. Beck himself, shows buildings directly across the street from the window of his room. His self-portrait appears as a reflection in the lower right windowpane, with his initials – “By LCB” – just below.

Below is a 2018 Oogle street view of the building directly across the street from Lieutenant Beck’s room. In 2019, it was the home of the Boulangerie pâtisserie chocolaterie à Anet (Chocolate Bakery Pastry Shop in Anet).

______________________________

Here are Lt. Beck’s last diary entries and final words to his parents, composed just prior to his departure from Anet, and, his ill-fated attempt to return to Allied forces:

It’s a very beautiful day today, the first nice sunny one in over a week. I shall just have to lie in the sun awhile, even though I won’t get much written. As I said previously, I was to leave at 8:00 o’clock at night. That was wrong, I find, after talking to Paulette about it. It was at 8:00 o’clock in the morning. That means that I don’t have tomorrow to write and so today must wind up my writing from France.

It has been lots of fun writing all this. I guess that I am just halfway glad that I got in on this part of the war. Just a few hours after I set my plane down in France, I thought to myself:

“Boy, what a story this will make.”

Even if I don’t get out of France, ever, this will, by mail, and that is one reason why I have taken it so seriously. Had I felt that it never would be read I should not have written so much.

Writing something like this that will not be mailed right away gives me a chance to say just anything I feel. If I get back to England and finally to America again, I can just tear up anything that was meant to be read if I were killed trying to get back. On the other hand, if I don’t make it, everything I have written will be here for anyone to read, and I feel it will make a better ending to my life than just to be “missing in action.”

No one wants to die like that — just without anyone knowing what happened. I feel then that I have really accomplished a great deal in leaving these passing thoughts behind. Hoping with all my heart that they will be of some comfort to all my friends, and especially to my Mom and Dad.

When you read all this I shall be right there looking over your shoulder. (You may not see me but I am here.) You can feel that I have not gone away, but have, instead, come back to you. (I am so much closer than I was in England and France.)

You should see my tan now. I’m either mighty dirty or very tan, one or the other. At least I like it and feel much more healthy when I’m brown, as I have told you before.

I’ll be darned if Larson didn’t bring me two packages of cigarettes. He must have killed two Jerries to get them. What a guy!!!

How can a guy feel sad and lonely with someone doing everything in the world for you – ?

Mom, if you will, I’d like you to write a letter to Paulette and to Larson. They can get the French lady I spoke of, to translate it for them. You can write two or just one letter — suit yourself. Address it to Larson Roland, Anet, France.

He has lived here all his life and everyone knows him. Also, if you like, you can ask them to write and tell you just what happened. You will want to know I am sure and if there is any way humanly possible, they will find out and write you.

So, as this lovely day draws to an end, so does my writing. Always remember this saying which you put at the bottom of so many of your letters. It is truly a short, sincere, and very simple statement but holds a world of comfort and thought:

“Keep smiling.”

I have kept smiling every day and it has made each day of my life joyously happy. Just remember me as always smiling, Mom. And now it is you and Dad who must, “Keep your chin up” and “Keep smiling”, always.

I shall always be, Your loving son

— L.C.—

______________________________

Earlier in the text appears a letter to an unknown “Helen”:

Helen,

You didn’t think I would forget you, did you?

After knowing a girl as lovely as you, for twelve years, a guy would be absolutely a “dope” if he did!

Thinking of all our wonderful times together is easy but to forget them would take more than a lifetime.

I guess something must have gone wrong with the machine that “puts names on bullets”. We both were quite sure, weren’t we? I really felt that I would live to be a hundred, but I suppose I can say, quite safely, that in my 24 years I have had my share of living.

It’s always nicer, anyway, to end a story at its best climax. My story ends just as I like it. Full of thrills and excitement and with the blood tingling in my veins — Fighting.

I guess there isn’t much else to say. You know how I always was about such things. Perhaps leaving things unsaid at times is better. Just now, anything I say might sound foolish or untrue. Perhaps it would be, but when a person writes a note of this type he doesn’t very often say things he doesn’t mean.

If you can see my point I shall only say this and no more.

I loved you dearly when we were at our best. You must have known. Surely you could tell. As for some of the time, I will admit that I wasn’t sure.

Our love affair was, ’tis true, quite irregular and although it might have been better, I shall always think of it as a very wonderful part of my life.

Perhaps had we been a bit older when we met and I a bit more settled, as well as you, we would have been married.

As it turned out you are much better off as you would be a widow now instead of a beautiful young girl, with a fine future ahead of you.

Well, “Sweet Stuff,” I shall say Byeeeee now, with a kiss for old times.

I want to wish you every happiness that can be yours.

Until we meet again — I shall be waiting.

Love, L. C.

______________________________

Finally, just before his departure from Anet:

If anything happens to me, I hope that you can finish my story. It would be my last wish and I think a very nice way to end a thus far, perfectly swell life. Naturally, I truly hope that I shall be able to finish the story myself, but if not, the ending will be for you to finish. Paulette will have someone write you and tell you just what happened, if the French Underground can find out. This is quite an unhappy little note, isn’t it? I feel much the opposite, however.

______________________________

______________________________

Here are images of four of the pilots mentioned by Beck, or, appearing in the group photograph above.

This is “Dorsey III”, namely, Isham “Ike” Jenkins Dorsey III, of Opelika, Alabama. He survived the war. Contributed by his brother, David “Whitt” Dorsey, this photo appears at Isham Dorsey III’s commemorative page at the Registry of the National WW II Memorial.

______________________________

______________________________

“Unger”, mentioned in the account of Beck’s last mission, is listed in Fighter Pilot as “Lt. Edwin H. Unger, Jr., New York, N.Y.” His image, as an aviation cadet, appears in a composite of photographic portraits of servicemen from Nassau, New York, in the Nassau Daily Review-Star of May 26, 1944, accessed via Thomas N. Tyrniski’s FultonHistory website. (That’s where the “If you are reading this you have too much time on your hands.” is from!) Lt. Unger survived the war.

______________________________

This is Major Chester L. Van Etten of Los Angeles, who’s seen (wearing RCAF or RAF wings) in the center of the above group photo. This image, also at the Registry of the National WW II Memorial, appears in a commemorative page created by Chester L. Van Etten himself.

______________________________

Also appearing at the WW II Memorial Registry is this image of Lt. Bryant L. Cramer, appearing on a commemorative page created by his grand-daughter, Cara Montrief. Given the markings on the P-47s cowl, I assume that this image was taken in the Continental United States.

Here’s Lt. Cramer’s portrait, taken in August of 1943, from the National Archives’ collection “Photographic Prints of Air Cadets and Officers, Air Crew, and Notables in the History of Aviation“.

References

References

Beck, Levitt C., Jr. (Beck, Levitt C., Sr.), Fighter Pilot, Mr. and Mrs. Levitt C. Beck, Sr., Huntington Park, Ca., 1946

Chorley, W.R., Royal Air Force Bomber Command Losses of the Second World War Volume 5 – 1944, Midland Publishing, Hinckley, England, 1997

USAF Credits for the Destruction of Enemy Aircraft, World War II – USAF Historical Study No. 85, Albert F. Simpson Historical Research Center, Air University, 1978

First Lieutenant Levitt Clinton Beck., Jr. – FindAGrave biographical profile

P-47D 42-8473 “Bloom’s Tomb” – at 406th Fighter Group

Lancaster ND533 – at Aerosteles

Lancaster ND533 – at North East War Memorials Project

Lancaster ND533 – at WW2 Talk

Jacques Desoubrie – at Wikipedia

Allied Airmen at Buchenwald – at Wikipedia

Allied Airmen at Buchenwald – at National Museum of the United States Air Force

Squadron Leader Phillip John Lamason, DFC & Bar – at Wikipedia