Just a little humor…!

(Published in The New Yorker some time in November of 1991. Not sure of the artist’s name.)

Images and Thoughts to Inspire Your Intellect and Infuse Your Imagination!

Note!… Originally created in March of 2020, I’ve updated this post to include a comment by Brett Bayne, which follows:

Hello,

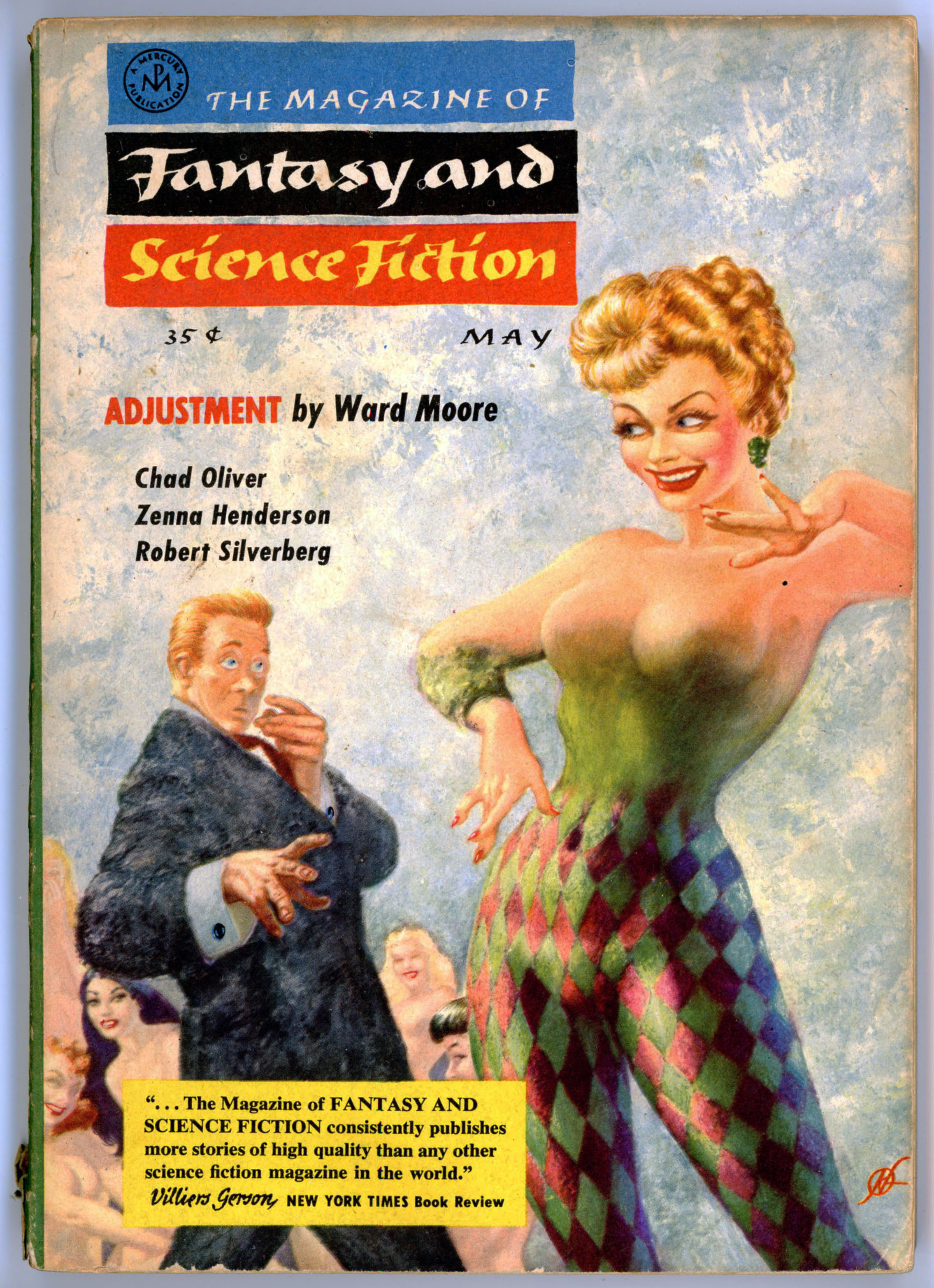

I have just finished reading your fascinating and informative blog post about Ward Moore’s story “Adjustment,” published in the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, and featuring cover art by Frank Kelly Freas. You helpfully included a link to a PDF of the story. Thank you for that. Here’s my question: Is the young woman depicted in the original painting supposed to be Lucille Ball? It sure looks like her!

Let me know your thoughts.

Many thanks,

Brett Bayne in L.A.

I present my thoughts about Mr. Bayne’s question below…!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Like other science fiction artists, Frank Kelly Freas’ works display a certain style that makes them immediately (well, almost immediately!) identifiable.

Though he was more than capable of rendering the human figure in a purely representative and natural form, the distinctive “quality” of Freas’ compositions seems to lie in the very faces of the central or most prominent figures in his compositions. These are often exaggerated in dimension, proportion, or shape, making them symbolically “fit” the mood of the story, and, the character’s specific role within it.

Case in point, the cover of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction for May of 1957, illustrating a scene from Ward Moore’s tale “Adjustment”. The surprised and utterly abashed fellow on the left is “Mr. Squith” (great choice of surname – though “Mr. Squish” or “Mr. Squid” would do just as well!), who, if not a hero in a classical sense – well, he’s no hero, in any sense! – is most assuredly the protagonist, albeit a protagonist of a passive and – to the reader – utterly exasperating sort.

Well. “Adjustment” might have been just a little risque in its day, but in the brittle and tired world of 2020, the tale has an air of quaintness, charm, and even innocence of a sort. Mr. Squith, it turns out, is rather oblivious to the nature of human social interactions, and the cues and signals – spoken and especially unspoken – that pass between people, in effect becoming the tale’s straight man and object of humor.

As for Freas’ art itself?

Well, here’s the cover as published…

…and, below is the cover – from Heritage Fine Auctions – as originally painted. (The painting was sold as part of an auction held on June 27- 28, 2012.)

…and, below is the cover – from Heritage Fine Auctions – as originally painted. (The painting was sold as part of an auction held on June 27- 28, 2012.)

Though I’m not certain of the details, it seems that the editors of Fantasy and Science Fiction had second thoughts about Freas’ cover as originally created, with Freas adjusting the art for “Adjustment” accordingly. Likewise, the promotional blurb about the magazine itself – which typically appeared on the rear cover, if at all – was strategically located to the front.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

And now for something sort of different. Well, uh, divertingly different… Well. You know.

Yes, even when I created this post four years ago (now being 2024), I was immediately struck by the similarities (exaggerated similarities, but similarities nonetheless) between the “face” (not * ahem * physiognomy) of the woman on Freas’ cover – most immediately attracting the attention and astonishment of our preternaturally naive and (alas) erotically oblivious protagonist, Mr. Squith – and that of Lucille Ball. I didn’t write as much at the time, but this is especially so in light of the pleasing but very generic faces of the bemused ladies at lower left. Mr. Squith’s lady is very much an individual. A recognizable individual. An identifiable individual.

By way of comparison, three pictures of Lucille Ball are shown below.

The verdict? No coincidence.

In other words, “Here’s Lucy!”

“I Love Lucy” 1958 promo image.

New York Post, August 4, 2021: “Rare tapes revealed: Lucille Ball has SiriusXM podcast decades after death”

New York Post, August 4, 2021: “Rare tapes revealed: Lucille Ball has SiriusXM podcast decades after death”

Cast of I Love Lucy with William Frawley, Desi Arnaz, and Vivian Vance – Undated photo. “The Lucy-Desi Comedy Hour aired on CBS from 1962 to 1967. … The photo has only a “date use” stamp for 27 April 1989, which is the day after Lucille Ball’s death. The photo was apparently kept in the newspaper’s photo files after it was received and not published in that respective newspaper until after Ball’s death.”

Cast of I Love Lucy with William Frawley, Desi Arnaz, and Vivian Vance – Undated photo. “The Lucy-Desi Comedy Hour aired on CBS from 1962 to 1967. … The photo has only a “date use” stamp for 27 April 1989, which is the day after Lucille Ball’s death. The photo was apparently kept in the newspaper’s photo files after it was received and not published in that respective newspaper until after Ball’s death.”

You can read Mr. Squith’s adventure here, and about Lucy Ball at Wikipedia.

Alas, poor, naive Mr. Squith…

March 12, 2020 – 320

This cartoon, by The New Yorker cartoonist George Price, is hilarious, for it takes a commonplace idea – a literary idea – and carries it to an (il)logical conclusion. More than the merely weird idea of assembling all the authors of a anthology’s collected works for a single book signing, the appearance, facial expression, and attire of every individual is unique, exaggeratingly embodying the life experience of every author. It’s this, combined with the hilarity of a collective book signing, makes the cartoon work so well.

____________________

____________________

Price’s cartoon reminds me of the cover of the October, 1952 issue of Galaxy Science Fiction, which featured depictions of twenty contributors (excluding “Bug-Eye”) who were making the by then two-year-old magazine a success. A very clever idea. The magazine leads with a report to its readers touching upon its successes, challenges, and plans for the future, and mentions upcoming works by Isaac Asimov and Clifford Simak, and, includes a key – reproduced below – identifying the authors and contributors shown on the cover.

____________________

Annual Report to our Readers

The twelvemonth between our first annual report and this, which marks the beginning of our third year, was rammed full of activity for GALAXY. It all boils down to this one astonishing fact, however:

GALAXY has acquired the second largest circulation in science- fiction and is pushing hard toward first place.

For a magazine to achieve this record in so short a time is a tribute to its unyielding policy of presenting the highest quality obtainable; to its readers for their loyalty and appreciation; to its authors for helping it maintain those standards and even advance them.

During the turbulent first year of GALAXY’s existence, other publishers thought the idea of offering mature science fiction in attractive, adult format was downright funny. They knew what sold – shapely female endomorphs with bronze bras, embattled male mesomorphs clad in muscle, and frightful alien monsters in search of a human meal.

Even our former publisher [World Editions, Inc., 105 West 40th St., New York, N.Y. – not this contemporary World Editions!] became infected with that attitude, and the resulting internal conflicts were no joke at all. But now:

• We have the biggest promotion campaign mapped out that any science fiction magazine has ever had.

• We are working out the broadest circulation possible. Note that we reach the stands regularly on the second Friday of each month. (Subscribers, however, get their copies at least five to ten days before.)

• Better printing, paper and reproduction of art lie ahead.

• These new art techniques I mentioned in the past are on their way. They were stubborn things to conquer, but you’ll be seeing them soon.

• If you want to find WILLY LEY in a science fiction magazine henceforth, you’ll have to buy GALAXY. As our science editor, he will work exclusively for us in this field.

• Last and by far the most important, the literary quality of GALAXY will continue to be a rising curve – as steeply rising as we can manage.

Coming up, for example:

• November: THE MARTIAN WAY by Isaac Asimov, a novella, that introduces problems and situations in space travel that I have never seen before,.

• December: RING AROUND THE SUN by Clifford D. Simak is a powerful new serial with a startling theme and one surprising development after another.

• March: After the conclusion of the Simak serial, we have THE OLD DIE RICH by a chap named Gold. Naturally, the story was read by impartial critics – no writer can judge his own work – and they report it’s GALAXY quality. I hope you’ll agree with them.

Yes, it’s been a fine year. Next year looks even better.

– H.L. GOLD

____________________

1 – Fritz Leiber (“Gonna’ Roll the Bones”)

2 – Evelyn Paige

3 – Robert A. Heinlein

4 – Katherine MacLean (Dragons and such)

5 – Chesley Bonestell

6 – Theodore Sturgeon

7 – Damon Knight (“To Serve Man”)

8 – H.L. (Horace L.) Gold

9 – Robert Guinn

10 – Joan De Mario

11 – Charles J. Robot

12 – Cyril Kornbluth

13 – E.A. (Edmund A.) Emshwiller

14 – Willy Ley

15 – F.L. Wallace

16 – Isaac Asimov

17 – Jerry Edelberg

18 – Groff Conklin (anthologist)

19 – John Anderson

20 – Ray Bradbury (“The Fireman” (“Fahrenheit 451”))

21 – Bug Eye

____________________

____________________

But, where did Horace Gold get the very idea to acknowledge people instrumental to Galaxy’s success, in such a clever way?

I don’t know.

But, while perusing the contents of other, lesser known magazines at the Luminist Archive, I came across the November, 1951 issue of Marvel Science Fiction, which features cover art by Hannes Bok, in his own immediately recognizable style…

____________________

…and this two-page cartoon of the members of the by then four-year-old “Hydra Club”, an organization of professionals in the field of science fiction. Though far more “busy” than the scene depicted on the cover of Galaxy, the design is remarkably similar, right down to the number key at the bottom of the cartoon, and, the accompanying diagram of “who’s who” at lower right, the names of “who” are all listed below.

Was this the inspiration for Horace Gold, or, art director W.I. Van Der Poel? Given the timing, could be!

THE HYDRA CLUB

Text by Judith Merril

(Illustration by Harry Harrison)

An organization of Professional Science Fiction Writers, Artists and Editors.

Article One: The name of this organization shall be the Hydra Club.

Article Two: The purpose of this organization shall be…

PUZZLED silence greeted the reader as he lay down the proposed draft of a constitution, and looked hopefully at the eight other people in the room.

“The rest of it was easy,” he explained, “but we spent a whole evening trying to think of something for that.”

“Strike out the paragraph,” someone said. “We just haven’t got a purpose.”

And so we did. The Hydra Club was, officially, and with no malice in the forethought, formed as an organization with no function at all. It was to meet twice a month; it hoped to acquire a regular meeting place and a library of science fiction; its membership was to be selected on no other basis than the liking and approval of the charter members, who organized themselves into a Permanent Membership Committee for the new club.

That was in September, 1947. In four years of existence, the club has increased sevenfold. Its roster now lists more than sixty members, and the number is that low only because of the strict stipulation that admission to membership is by invitation only. There is no way for a would-be member to apply for admission; and invitations are issued only after the holding a complex secret-ballot blackball vote.

Of the nine charter members of the club, five are still active on the Permanent Membership Committee. Lester del Rey, who had been absent from the science fiction field entirely for several years, when the club was started, is now once again a leading name in the field. Dave Kyle and Marty Greenberg, who first met each other in the organizational days of the club, have since become partners in a publishing firm, Prime Press. Fred Pohl, who was then still writing an occasional story under the pen-name of James MacCreigh, has developed the then still-struggling Dirk Wylie agency into the foremost literary agency in the science fiction field. And yr. humble correspondent, who had just a few months earlier written her first science fiction story, has since become, among other things, Mrs. Frederik Pohl.

There are half a hundred other names on the rolls, many of which would be completely unfamiliar to science fiction fandom. The Club has never attempted to limit its membership to professionals working in the field. It has endeavored only to gather together as many congenial persons as possible. In the four years of its existence there have been many changes in character, constitution, solvency, and situation. A considerable library has been acquired by gift and donation, but no permanent meeting place or library space has ever been found. Meetings are now held only once a month, sometimes in the studio apartment of the Pratts’, or that of Basil Davenport, more often in a rented hall. From time to time, under the impetus of an unwonted ambition, the club has even initiated major endeavors, and less frequently has actually carried them through.

The single exception to this renewed enthusiasm for purposelessness is the annual Christmas party … perhaps because we have found it possible for all concerned to have a remarkably good time at these affairs in return for an equally remarkably small output of work. The success of the annual parties has rested largely on the willingness of member talent to be entertaining (and the dependable willingness of the guests to amuse themselves at the bar). At such times, there is little holding back. Why watch television, after all, or empty your pockets for a Broadway show, if you can have Willy and Olga Ley explain with words and gestures the structure of the Martian language – or watch your best friends cavort through a stefantic satire devised in the more mysterious byways of Fred Brown’s Other Mind – or listen yearly to a new and even funnier monologue delivered by Philip-William (Child’s Play) Klass-Tenn?

Between this yearly Big Events, club meetings very considerably in character. A member may arrive, on any given meeting date, to find a scant dozen seriously debating the date of publication of the second issue of Hugo Gernsback’s third magazine – or to find seventy-off slightly soused guests and members engaged in the most frantic of socializing, to the apparent exclusion of science fiction as a topic of interest. At these larger meetings, it takes a knowing eye to detect the quiet conversation in the corner where a new line of science fiction books has just been launched, or to understand that the clinking of glasses up front center indicates the formation of a new collaborating team.

Perhaps one of the most unlikely and most pleasant things about the Hydra Club is the way it manages to contain in amity a membership not only of writers and artists, but also of editors and publishers. We like to think that it is due to the “by invitation only” policy, and to the profound wisdom of our P.M.C., that the lions and the lambs have been induced to lie down so meekly all over the place. Even rival anthologists and agents are seen smiling at each other from time to time, and the senior editor of a large publishing house is always willing to pass on advice to newcomer specialist publishers. There are thirty-odd magazine writers in the crowd, and ten or more magazine editors – and still not a fistfight in a barload!

Hydra members are selected for interest, individuality, intelligence, and an inquiring mind, a combination unique among science-fiction organizations in my knowledge, we have now achieved four years of existence without a single major internal feud. What difficulties have arisen in relation to the club, from the outside, appear to be entirely due to the fact that, without trying, Hydra has become an increasingly important group in the professional field. But the business that takes place in and around the Hydra Club remains incidental.

When bigger and better purposes for clubs are found, the Hydra Club will still point happily to its nonexistent Article Two.

____________________

1 – Lois Miles Gillespie

2 – H. Beam Piper

3 – David A. Kyle

4 – Judith Merril Pohl

5 – Frederik Pohl

6 – Philip Klass

7 – Richard Wilson

8 – Isaac Asimov, Ph.D.

9 – James A. Williams

10 – Martin Greenberg (anthologist)

11 – Sam Merwin, Jr.

12 – Walter I. Bradbury

13 – Bruce Elliott

14 – J. Jerome Stanton

15 – Jerome Bixby (Twilight Zone!)

16 – Basil Davenport

17 – Robert W. Lowndes

18 – Olga Ley (Willy’s wife)

19 – Oswald Train

20 – Charles Dye

21 – Frank Belknap Long

22 – Damon Knight

23 – Thomas S. Gardner, Ph.D.

24 – Harry Harrison

25 – Sam Browne

26 – Groff Conklin

27 – Larry T. Shaw

28 – Lester del Rey

29 – Frederic Brown

30 – Margaret Bertrand

31 – Evelyn Harrison

32 – L. Sprague de Camo

33 – Theodore Sturgeon

34 – George C. Smith

35 – Has Stefan Santessen

36 – Fletcher Pratt

37 – Willy Ley (Olga’s husband)

38 – Katherine MacLean Dye

39 – Daniel Keyes

40 – H.L. (Horace L.) Gold

41 – Walter Kublius

____________________

____________________

For your amusement…

Here’s the book where I found George Price’s cartoon…

Price, George (Introduced by Alistair Cooke), The World of George Price – A 55-Year Retrospective, Harper & Row, New York, N.Y., 1989

George Price, at…

… Art.com

Hydra Club, at…

… That’s My Skull (Judith Merril’s article, and, accompanying illustration)

“…writing is different because you do not have to learn or practise…”

____________________

“Kissing your hand may make you feel very good but a diamond bracelet lasts forever.”

____________________

Bergey, Bergey, Bergey!…

Earle K. Bergey, cover illustrator of mainstream publications, pulp magazines, and paperbacks – all in a variety of genres – produced a body of work that while more conventional in terms of subject matter than that of artists like Frank Kelly Freas or Edmund Emshwiller, is eye-catchingly distinctive, and is truly emblematic of mid-twentieth-century illustration.

His science-fiction art commenced in the late 1930s and continued until his untimely death in 1952 … see examples here, here, and here. As described at Wikipedia, his, “…science fiction covers, sometimes described as “Bim, BEM, Bum,” usually featured a woman being menaced by a Bug-Eyed Monster, alien, or robot, with an heroic male astronaut coming to her assistance. The bikini-tops he painted often resembled coppery metal, giving rise to the phrase “the girl in the brass bra,” used in reference to this sort of art. Visionaries in TV and film have been influenced by Bergey’s work. Gene Roddenberry, for example, provided his production designer for Star Trek with examples of Bergey’s futuristic pulp covers. The artist’s illustrations of scantily-clad women surviving in outer space served as an inspiration for Princess Leia‘s slave-girl outfit in Return of the Jedi, and Madonna’s conical brass brassiere.”

An example? The Spring, 1944, issue of Thrilling Wonder Stories.

Commencing in 1948, Bergey became heavily involved in creating cover art for paperbacks. This began with Popular Library’s 1948 edition of Anita Loos’ Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, which was first published in 1925. Though the book is a light-hearted work of conventional fiction (perhaps lightly semi-autobiographical; perhaps loosely inspired by fact), Bergey’s cover is a sort-of…, kind-of…, maybe…, perhaps…, well…, variation on a theme of “Good Girl Art” characteristic of American fiction of the mid-twentieth-century, and likewise is a stylistic segue from Bergey’s science fiction pulp cover art. Sans shining copper brassiere, however.

Here is it…

From Bergey’s biographical profile at Wikipedia, here’s an image of the book’s original cover art. The only information about the painting (does it still exist?) is that it’s “oil on board”.

A notable aspect of this painting, aside from the extraordinarily and deliberately idealized depiction … exaggeration?! … of Miss Lorelei Lee (looks like she’s being illuminated by a klieg light, doesn’t it?) is the appearance of the men around her, each of whom is each vastly more caricature than character. Well, exaggeration can work in two directions.

____________________

She was a

GIVE AND TAKE GIRL

Lorelei Lee was a cute number with lots of sex

appeal and the ability to make it pay off.

With her curious girl friend, Dorothy,

she embarked on a tour of England and the

Continent. And none of the men who crossed

their path was ever the same again.

When one of Lorelei’s admirers sent her a

diary she decided to write about her

adventures. They began with Gus Eisman, the

Button King, who wanted to improve her “mind”

and reached a climax in her society debut

party – a three-day circus that rocked

Broadway to its foundations.

A hilarious field study of the American

chorus girl in action set down in her

own inimitable style!

____________________

Lorelei Lee’s appearance in Ralph Barton’s cartoons in the 1925 edition of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes is – wellll, granting that they’re just cartoons; thirty-three appear in the book – vastly less exaggerated than her depiction on Bergey’s cover. Three of his cartoons are shown below…

____________________

It would be strange if I turn out to be an authoress.

I mean at my home near Little Rock, Arkansas,

my family all wanted me to do something about my music.

Because all of my friends said I had talent and they all kept after me and kept after me about practising.

But some way I never seemed to care so much about practising.

I mean I simply could not sit for hours at a time practising just for the sake of a career.

So one day I got quite tempermental and threw the old mandolin clear across the room

and I have never really touched it since.

But writing is different because you do not have to learn or practise

and it is more tempermental because practising seems to take all the temperment out of me.

So now I really almost have to smile because I have just noticed

that I have written clear across two pages onto March 18th, so this will do for today and tomorrow.

And it just shows how tempermental I am when I get started. (Illustration p. 13)

____________________

“Kissing your hand may make you feel very good but a diamond bracelet lasts forever.” (Illustration p. 101)

____________________

“Dr. Froyd seemed to think that I was quite a famous case.” (Illustration p. 157)

____________________

What would be the book without the movie? Here’s Howard Hawks’ 1953 production of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, at Network Film’s YouTube channel.

A qualifier: Despite being a movie aficionado and voracious reader, I’ve not actually viewed this movie, for … despite being able to appreciate and enjoy most any genre of film … I’ve absolutely never been a fan of musicals. (Ick.)

What would Gentlemen Prefer Blondes be without “Diamond’s Are a Girl’s Best Friend”? (Starts at 59:00 in the film.) The idea of a rotating chandelier formed of women strikes me as really bizarre, if not disturbing… Oh, well.

____________________

____________________

Some Other Things…

Anita Loos…

…at Wikipedia

…at Brittanica.com

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes…

…at Archive.org (“Gentlemen prefer blondes” : the illuminating diary of a professional lady, Boni & Liveright, New York, N.Y., 1925)

…at Wikipedia

Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend…

…at Wikipedia

…at Genius.com (lyrics)

Earle K. Bergey…

…at Wikipedia

Dating from March of 2018, I’ve now updated this post to display the cover of a much better copy of Rembrandt’s Hat, than which originally appeared here. The “original” cover image can be viewed at the “bottom” of the post.

I’ve also – gadzooks, at last! – discovered the identity of the book’s previously-unknown-to-me-illustrator, whose initials, “A.M.” appear on the book’s cover. He’s Alan Magee, about whom you can read more here.

And, a chronological compilation of Bernard Malamud’s short stories can be found here.

Contents

The Silver Crown, from Playboy (December, 1972)

Man in the Drawer, from The Atlantic (April, 1968)

The Letter, from Esquire (August, 1972)

In Retirement, from The Atlantic (March, 1973)

Rembrandt’s Hat, from New Yorker (March 17, 1973)

Notes From a Lady At a Dinner Party, from Harper’s Magazine (February, 1973)

My Son the Murderer, from Esquire (November, 1968)

Talking Horse, from The Atlantic (August, 1972)

______________________________

Half a year later, on his thirty-sixth birthday,

Arkin, thinking of his lost cowboy hat

and heaving heard from the Fine Arts secretary that Rubin was home

sitting shiva for his recently deceased mother,

was drawn to the sculptor’s studio –

a jungle of stone and iron figures –

to search for the hat.

He found a discarded welder’s helmet but nothing he could call a cowboy hat.

Arkin spent hours in the large sky-lighted studio,

minutely inspecting the sculptor’s work in welded triangular iron pieces,

set amid broken stone sanctuary he had been collecting for years –

decorative garden figures placed charmingly among iron flowers seeking daylight.

Flowers were what Rubin was mostly into now,

on long stalk with small corollas,

on short stalks with petaled blooms.

Some of the flowers were mosaics of triangles.

Now both of them evaded the other;

but after a period of rarely meeting,

they began, ironically, Arkin thought, to encounter one another everywhere –

even in the streets of various neighborhoods,

especially near galleries on Madison, or Fifty-seventh, or in Soho;

or on entering or leaving movie houses,

and on occasion about to go into stores near the art school;

each of them hastily crossed the street to skirt the other;

twice ending up standing close by on the sidewalk.

In the art school both refused to serve together on committees.

One, if he entered the lavatory and saw the other,

stepped outside and remained a distance away till he had left.

Each hurried to be first into the basement cafeteria at lunch time

because when one followed the other in

and observed him standing on line at the counter,

or already eating at a table, alone or in the company of colleagues,

invariably he left and had his meal elsewhere.

Once, when they came together they hurriedly departed together.

After often losing out to Rabin,

who could get to the cafeteria easily from his studio,

Arkin began to eat sandwiches in his office.

Each had become a greater burden to the other, Arkin felt,

than he would have been if only one were doing the shunning.

Each was in the other’s mind to a degree and extent that bored him.

When they met unexpectedly in the building after turning a corner or opening a door,

or had come face-to-face on the stairs, one glanced at the other’s head to see what, if anything,

adorned it; then they hurried by, or away in opposite directions.

Arkin as a rule wore no hat unless he had a cold,

then he usually wore a black woolen knit hat all day;

and Rubin lately affected a railroad engineer’s cap.

The art historian felt a growth of repugnance for the other.

He hated Rubin for hating him and beheld hatred in Rubin’s eyes.

“It’s your doing,” he heard himself mutter to himself to the other.

“You brought me to this, it’s on your head.”

After hatred came coldness.

Each froze the other out of his life; or froze him in. (pp. 130-131)

March 25, 2018 255

While the cover art of the Washington Square Press edition of Famous Chinese Short Stories is, well, nice, it’s nothing so dramatic in visual impact as to “make me write home about”. (Or * ahem * specifically blog about.) Rather, I’m presenting this book by virtue of its content, which is excellent, if not fascinating, if not enchanting.

Notably, Lin Yutang is listed as neither the compiler nor the editor of the twenty tales comprising this collection. Rather, he is dubbed is a reteller: The stories herein have not simply been collected-and-there-you-have-them-and-no-more, a la science fiction anthologies by Asimov & Greenberg, Knight, Conklin, Bleiler & Dikty, or, Wollheim. Likewise, they are probably not direct translations from original manuscripts or sources, regardless of wherever and whenever those documents may have originated. Rather, Lin Yutang has modified the stories – to an indeterminate degree – to make them more accessible and appealing to a non-Chinese readership, in terms of plot, characters, and literary style.

In this, he has succeeded. While I have no idea if these stories actually are genuinely significant in terms of Chinese literature and culture, I immensely enjoyed this volume. The tales flow rapidly, and from them one immediately gains a sense of the sheer universality of human experience, in terms of emotion, eroticism, relationships, love, fate and justice, and – yes – the supernatural, regardless of differences in history and language.

Contents

Adventure and Mystery

Curly-Beard, by Tu Kwang-t’ing

The White Monkey, by anonymous

The Stranger’s Note, by “Ch’ingp’ingshan T’ang”

Love

The Jade Goddess, by “Chingpen T’ungshu”

Chastity, a popular anecdote

Passion, by Yuan Chen

Chienniang, by Chen Hsuanyu

Madame D., by Lien Pu

Ghosts

Jealousy, by “Chingpen T’ungshu”

Jojo, by P’u Sung-ling

Juvenile

Cinderella, by Tuan Ch’eng-shih

The Cricket Boy, by P’u Sung-ling

Satire

The Poet’s Club, by Wang Chu

The Bookworm, by P’u Sung-ling

The Wolf of Chungshan (otherwise “The Wolf of Zhongshan“), by Hsieh Liang

Tales of Fancy and Humor

A Lodging for the Night, by Li Fu-yen

The Man Who Became a Fish, by Li Fu-yen

The Tiger, by Li Fu-yen

Matrimony Inn, by Li Fu-yen

The Drunkard’s Dream, by Li Kung-tso

A Reference or Two. Or three. (Perhaps four?) ((Even five?))

Famous Chinese Short Stories (this book itself!), at…

Lin Yutang, at…

… Wayback Machine (List of Lin Yutang’s Works)

Sometimes, you buy a magazine because of the content. Sometimes, you buy a magazine because of the cover. And a few times, you buy it for both. (But mostly, just for the cover…)

Case in point, The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction for March of 1980, which featured cover art by Gahan Wilson.

I’d already been somewhat familiar with his cartoons from The New Yorker, but seeing his unique and immediately identifiable work – in color, as a magazine cover – added an entirely new dimension (well, for me) to his oeuvre.

What stands out within this composition? The deliberately dingy atmosphere depicted by dint of darkly shaded green and gray; the goggle-eyed guy gazing in ghastly terror at his own reflection – from the chromed side of the Brave Little Toaster itself; the retinue of raggedy rats reflecting (ruefully?) on the scene revealed before them.

As indicated at the Visual Index of Science Fiction Cover Art, Wilson completed four covers for The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction. Aside from the issue below, the other three were featured in March and August of 1968, and, January of 1969. Among all four, I think that the composition shown in “this” post is easily the best.

Well, though I previously knew of the name “Thomas M. Disch”, by 1980, I’d not read any of his stories prior to that time. But (I thought his tale would be on the humorous side from the humor of Wilson’s cover…) I really enjoyed his story. A pure fantasy – not at all science fiction – it’s an upbeat adventure, and surprisingly substantive as well.

Happily, others realized the depth, fun, and merit of Disch’s story, and in 1987, his work was released as an animated film, directed by Jerry Rees. It’s a great adaptation; a little lighter in tone, perhaps, than the written version, but still true to Disch’s original idea. Simply put, the film is delightful, and in visual terms – viewed from the perspective of 2021 – refreshing and relaxing by virtue of having been completed well before (whew!) the advent of sophisticated CGI.

In his film review, Stephen Holden was entirely correct in writing, “Visually the movie has a smooth-flowing momentum and a lush storybook opulence that is miles away from the flat, jerky look of Saturday-morning cartoons. The fable of bored, squabbling playmates who become closer as they voyage into the unknown is unmarred by sentimentality and preachiness. At the same time, it exudes a sweetness and wit that should tickle anyone, regardless of age.”

Here’s Holden’s review, as it appeared in print, in The New York Times on May 31, 1989…

…and, a transcript of the review:

The Odyssey of a Band of Lonely Gadgets

By STEPHEN HOLDEN

It’s wake-up time in an empty mountain cabin, and the first appliance in the house to rouse itself is a jazzy-looking bedside radio that blares out an Al Jolson-style song. The noise quickly wakens the other appliances. The doggy-faced desk lamp flashes on, Kirby, the cranky, growling vacuum cleaner is ready for action, and Blankey, the meek, frightened electric blanket peeps awake. The most optimistic gadget is a toaster with a perky voice, big round eyes and a cute bowed smile. On this particular morning, the toaster tries to organize everyone into doing their usual chores. But without their master to use them, their existence seems lonely and purposeless.

Jerry Rees’s charming animated feature, “The Brave Little Toaster,” tells what happens when the appliances finally band together with a battered old desk chair using an old car battery for power, and embark on a journey to the city to find their master. If the film’s world of talking appliances with distinctive personalities has much in common with Pee-wee Herman’s Playhouse, its tone is more lyrical and dreamy than Mr. Herman’s squeaky, crowded Saturday-morning habitat. Their odyssey from the mountains to the city takes them through a redwood forest, into quicksand and over a waterfall. During the course of their journey, each traveler does something generous and brave, and the bonds between them strengthen.

Once they reach the city and are directed by a friendly traffic light to their master’s apartment, the appliances are dismayed to find themselves superseded by newer, more sophisticated technology. Ruling the apartment is a slick and snooty digital television set. Before their master comes home to find them, they are unceremoniously thrown out the window into a passing garbage truck. Only an act of heroism by the toaster prevents them all from being crushed for scrap in a junkyard.

“The Brave Little Toaster,” which opened a two-week engagement today at the Film Forum, brings one back nostalgically to the age when everyday household objects seemed to have faces and personalities. The screenplay by Mr. Dees and Joe Ranft, based on a novella by Thomas M. Disch, maintains a delightfully informal tone. The appliances are like any pack of kids. In moments of pique along their journey, they snap epithets like “chrome-dome,” “dialface,” and “slot-head” at one another.

Visually the movie has a smooth-flowing momentum and a lush storybook opulence that is miles away from the flat, jerky look of Saturday-morning cartoons. The fable of bored, squabbling playmates who become closer as they voyage into the unknown is unmarred by sentimentality and preachiness. At the same time, it exudes a sweetness and wit that should tickle anyone, regardless of age.

Several Appliances In Search of an Owner

THE BRAVE LITTLE TOASTER, directed by Jerry Rees; written by Mr. Rees and Joe Ranft, based on a novella by Thomas M. Disch; music by David Newman; produced by Donald Kushner and Thomas L. Wilhite; distributed by Hyperion Entertainment Inc. At Film Forum 1, 57 Watts Street. Running time: 90 minutes. This film has no rating.

Voices by: Jon Lovitz, Tim Stack, Timothy Day and Thurl Ravenscroft

Fortunately, the entire film can be viewed at YouTube. (Thus far.) Here it is:

References

Thomas Michael Disch

…at Wikipedia

…at Internet Speculative Fiction Database

Gahan A. Wilson

…at Wikipedia

…at GahanWilson.net

Stephen Holden

…at New York Times

Jerry Rees

Deanna Oliver (“Toaster”)

John Lovitz (“Radio”)

Timothy Stack (“Lampy” / “Zeke”)

Timothy E. Day (“Blanky” / “Young Rob”)

Thurl Ravenscroft (“Kirby”)

Phil Hartman (“Air Conditioner” / “Hanging Lamp”)

Unlike the cover art of Astounding Science Fiction, and most (but certainly not all!) of the cover art featured by its leading competitors, among them The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, if – Worlds of Science Fiction, and Amazing Science Fiction Stories, the cover illustrations of Galaxy Science Fiction, particularly from about 1955 through the early 1960s, was characterized by a sense of humor and whimsy, in the form of (obviously wordless!) visual social commentary.

Of this, the illustration below, by “Emsh” (Edmund A. Emshwiller) – entitled “Milady’s Boudoir”, is an excellent example, needing little elaboration. (-* Ahem.*-) Like other humorous Galaxy covers, the cover art is a “stand alone” image, entirely unrelated to the magazine’s literary content.

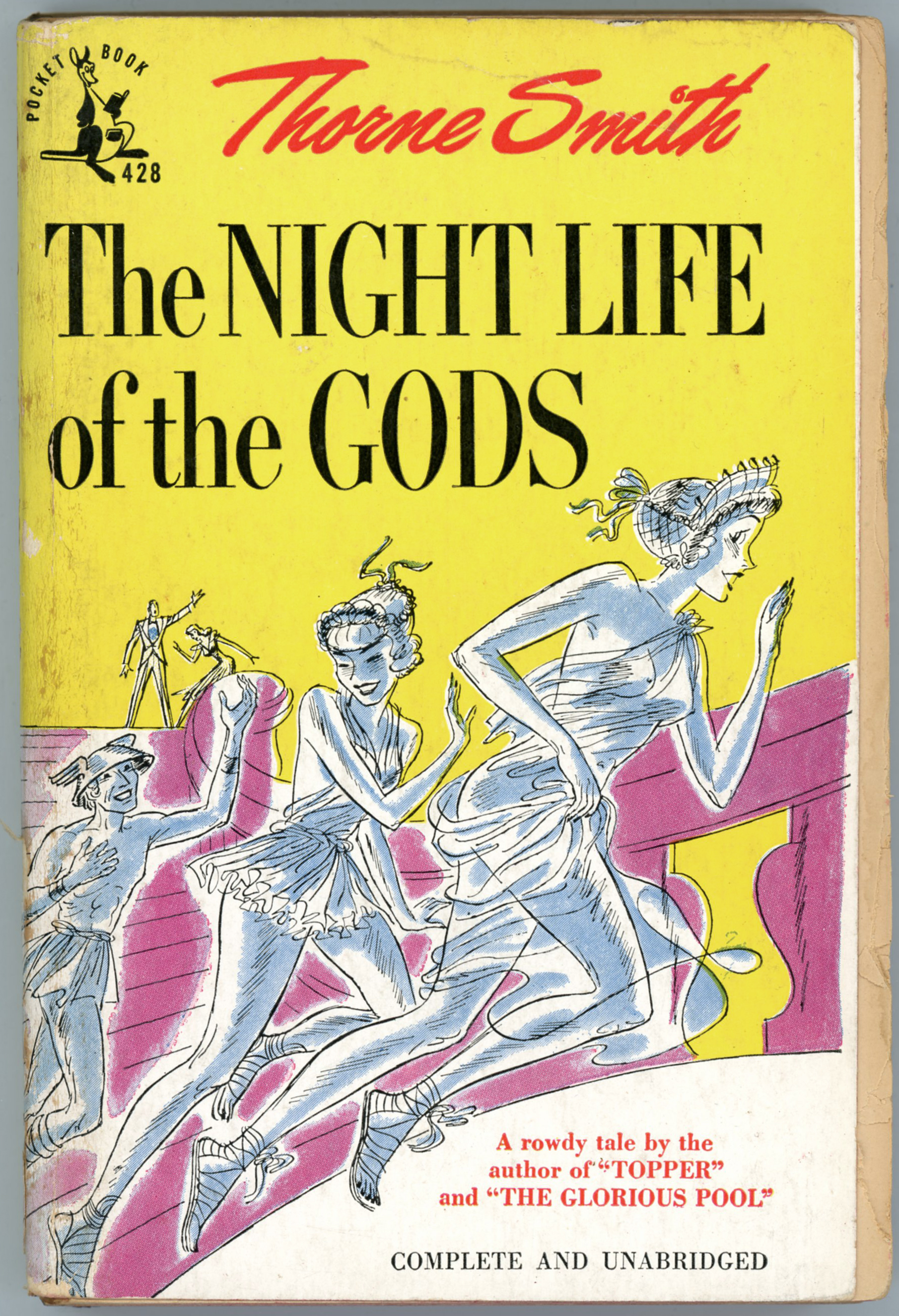

By the time Megara had initiated Mr. Hawk so well into her magic for turning statues into people

By the time Megara had initiated Mr. Hawk so well into her magic for turning statues into people

and back again that he would remember the simple ritual even when not quite sober,

no one was quite sober,

not even Megara herself.

As she had previously told him,

it was really a bang-up trick

and not so difficult to master if taken without applejack.

With his own discovery and Meg’s magic literally at the tips of his fingers,

Hunter Hawk,

with an emotion of exultation not entirely unbeholden to applejack,

felt himself well-equipped to face a new and eventful life. (64)