Almost a year and a half after the Collins Harvill publication of Life and Fate, Harper & Row released a paperback version of the novel with a striking cover illustration by Christopher Zacharow. The image depicts German and Soviet military helmets conjoined at their bases to form a symbolic guard tower – with the diminutive silhouette of a guard within – overlooking the electric fence of a concentration camp or anonymous camp in the gulag.

Zacharow’s composition is a simple and bold representation of the ideological parallels shared by totalitarian political and social systems, even as those systems are at war with one another.

But even with that, a nearly-glowing patch of light – in an otherwise darkened bluish-grayish-greenish sky – appears above the distant horizon of Zacharow’s painting.

Sunset or sunrise?

I would like to think the latter.

(Especially in this summer of the year 2020.)

Ronald Hingley’s extensive New York Times review of Life and Fate covers the novel and its author in terms of history, biography (Grossman’s biography, that is), the book’s social and cultural genesis as a work of literature – in both the Soviet Union and the “West” – in terms of its quality as literature, and (as noted by H.T. Willetts in his 1985 review). Hingley also notes the centrality of the Jewish identity of some of the protagonists, particularly that of Viktor Shturm, in terms of the book’s plot and message. (Or, messages, for they are several: overlapping, complementing, and reinforcing one another.) His review concludes with a brief excerpt from the book; I’ve included extracts of two other passages to enhance this post.

Given the novel’s significance and fame, I’d long wondered if it was ever serialized as a radio program or television mini-series. The answer – which I discovered upon creating this post – is emphatically “yes” (yes!) on both counts.

In 1981, BBC Radio 4 serialized Life and Fate as a 13-part series, produced and directed by Alison Hindell. Apparently still available at the BBC and last broadcast in September of 2011, the episodes are entitled:

Abarchuk

Journey

Novikov’s Story

Anna’s Letter

Fortress Stalingrad

Lieutenant Peter Bach

Krymov in Moscow

Viktor and Lyuda

Vera and Her Pilot

Viktor and the Academy

Krymov and Zhena – Lovers Once

A Hero of the Soviet Union

Building 6/1 – Those Who Were Still Alive

The cast – based on episode titles – included Sara Kestelman, Janet Suzman, Kenneth Branagh, and David Tennant.

In October of 2012, a 12-episode television mini-series of Life and Fate was produced in the Russian Federation, by Sergey Ursulyak. Available through Amazon Prime Video (19 5-star reviews), the episodes, ranging in length between 36 and 49 minutes and available with English-language subtitles, comprise:

On the Front

A Sea of Red Tape

Time for Love

Breakthrough Looms

Inside House Number 6

Fading Hopes

All Seems Lost

Fallout

In Moscow

Persecution

Suspicion and Influence

Requiem for Stalingrad

You can view and read a review of the series at the YouTube Stalingrad Battle Data channel, which includes this notable comment:

“The film raises fundamental questions behind each individual story, but almost always it comes down to this one: how to remain humane in inhumane conditions, oppressed from all sides, with enemies in front as well as behind you.

This is simply one of the very best cast, acted and directed series on WWII and the Soviet era in general. Excellently played and directed, it’s not only a very good war film, it’s a very good film in absolute. It’s also an exploration of human nature, most characters having a deep personality and expressing it just fine.”

(Well, now that I’ve finished the latest season of The Expanse, I have something new to look forward to…)

________________________________________

Stalingrad and Stalin’s Terror

LIFE AND FATE

By Vasily Grossman

Translated by Robert Chandler

880 pp New York Harper & Row $22.50

By Ronald Hingley

The New York Times Book Review

March 9, 1986

Cover illustration of Harper & Row edition by Christopher Zacharow (Marian C. Zacharow). You can view a full view of the painting – it’s quite striking – at Fine Art America, the version above having been cropped to conform to the proportions of the book’s cover.

Cover illustration of Harper & Row edition by Christopher Zacharow (Marian C. Zacharow). You can view a full view of the painting – it’s quite striking – at Fine Art America, the version above having been cropped to conform to the proportions of the book’s cover.

________________________________________

(Vasiliy Grossman, in a wartime portrait on the book jacket of The Years of War.)

(Vasiliy Grossman, in a wartime portrait on the book jacket of The Years of War.)

________________________________________

AN important novel written in the Soviet Union will almost certainly prove unpublishable there, but it will usually find its way to the West sooner or later. In the case of Vasily Grossman’s “Life and Fate” this has happened much later rather than sooner. Grossman’s novel was completed in I960. In other words it was written at about the same time as Boris Pasternak’s “Doctor Zhivago,” the work with which the practice of smuggling out illicit writings began 30 years ago.

“Life and Fate” hinges on the closing phase of the Battle of Stalingrad in the bleak winter of 1942-43, when the Soviet Army held and then routed the German invader on the Volga. But the action is by no means confined to that river. It also ranges through Soviet and German-occupied Eastern Europe, giving detailed vistas of front and rear, depicting mass atrocities and penal procedures on both sides. The text is nearly 900 pages and the named characters are legion.

Grossman’s faults are the usual faults Socialist Realists as exemplified in hundreds of run-of-the-mill Soviet works of fiction published over the last half century. The extraordinary thing is to find this puddingy and conformist technique employed by an author who has so triumphantly rejected the political conformism that is supposed to go with the technique. And the novel indeed does triumph in the end, defects and all, stodge or no stodge. It triumphs through the high seriousness of Grossman’s grand theme and through his compelling historical, moral and political preoccupations.

Notable among these is his faith in erratic, spontaneous, unscripted human kindness, as preached from inside a German death camp by a certain Ikonnikov, one of those saintly, philosophizing half-wits so beloved of Russian fiction writers. Such (as it were) extracurricular kindness is seen as an ineradicable human characteristic. It is presented as the sole guarantee that victory need not go in the end to the world’s great cruel ideologies, among which Ikonnikov does not hesitate to include Christianity alongside Marxism and Nazism. The thesis may sound trite, but Grossman illustrates it poignantly.

The prehistory of the book goes back to 1943, when Grossman began work on an earlier, widely forgotten novel entitled “For a Just Cause.” That book hinges on the opening phase of the Battle of Stalingrad, it was published in Moscow in 1952, and Grossman conceived it as the first part of a double-decker work of which “Life and Fate” was to form the second. As things worked out, it was not until 1980 that “Life and Fate” first achieved full publication in Russian, in Lausanne, Switzerland. And only now do we at last haw it in English translation.

What of the relations between these two linked novels? Subplots and major characters straddle them, though not to the extent of making the sequel impenetrably obscure to those ignorant of the predecessor. Closely linked-in this way, the two works yet offer a sharp contrast in political attitude. It is a contrast between the conformism of the earlier volume and the militant nonconformism of the later.

“For a Just Cause” was only another sample of Socialist Realist (that is, caponized) fiction, and it was even described as a potential Stalin Prize winner. True, the first published version came under attack and had to be rewritten. But that happened even to the most orthodox of Stalinist authors. And Grossman’s revised text was soon appearing in the Soviet Union. Its author never became what is now known as a dissident. Nor did he ever stray far from favor with authority. He served on the presidium of the Soviet Writers’ Union for 10 years until his death in 1964. He also won an official decoration, the Banner of Labor, for his writings.

THUS, the news that he was working on a sequel to “For a Just Cause” in the late 1950s would have been unlikely to create a stir in the Soviet Union or anywhere else. All that could be expected was another gelded fictional brontosaurus like its predecessor, the umpteenth such carcass to litter the landscape of officially approved Soviet literature. Who was to suspect that there was another, a secret, Grossman, a Grossman painfully aware that his own Government was responsible for a large share of the appalling sufferings that assailed Europe during his middle life? Here, it turns out, was a loather of totalitarianism in both its guises, the Stalinist no less than the Hitlerite. “Life and Fate” is a passionate onslaught against state-sponsored political terror.

Having finished the novel, Grossman even dared to offer it for Soviet publication, only to have it piously rejected as anti-Soviet by the journal to which it had been submitted. Then two K.G.B. officers burst into the author’s home and removed every shred of paper and other material – including used typewriter ribbons – with any conceivable bearing on “Life and Fate.” Brooding on his loss and disinclined to re-create half a million words from memory, the author implored the party leadership to order the return of his typescript. His answer came from the ideological satrap Mikhail Suslov: there could be no question of publishing the novel for another 200 years. That is a telling tribute to its credentials, both as a work of art and as a politically heretical text.

When Grossman died a year or two later, he could have no reason to suppose that his most inflammatory product would ever see the light of day. Yet a microfilm of his text somehow survived – these things do happen in Russia – and was eventually spirited abroad.

In portraying Hitlerite and Stalinist totalitarianism as closely resembling each other, the novel is not unique among Soviet-banned works. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn has made a similar point, just as he has also tended to agree with Grossman in suggesting that Lenin rather than Stalin was the true founder of Soviet-style totalitarianism. But Grossman deploys these important arguments with a force and slant all his own.

His book is also remarkable for the attention given, by an author himself Jewish, to the Jewish situation. The hero is a Soviet Jewish nuclear physicist. Soviet persecution of Jews is a major theme – a shade anachronistical, for attitudes more characteristic of the Soviet Union in the late 40s are here attributed to the war period. But all that is nothing, of course, compared with the pages on the sufferings of Jews caught up in Hitler’s “final solution.” For example, the reader of “Life and Fate” enters a gas chamber and breathes in an asphyxiant, the notorious gas Zyklon B. You need a steady nerve to read parts of this novel.

________________________________________

The fate of many of them seemed so poignantly sad

that to speak of them in even the most tender, quiet, kind words

would have been like touching a heart torn open

with a rough and insensitive hand.

It was really quite impossible to speak of them at all..

________________________________________

Grossman also pictures the horrors of the Soviet death camps and takes the reader inside the unspeakable Lubyanka Pitson in Moscow. His account of Soviet life – penal, military and civilian – is encyclopedic and unblinkered. On the military side it embraces adventures in an encircled strongpoint in Stalingrad – artillery bombardments, air raids, hand-to-hand fighting, the relations between commanders and military commissars and life in the army on the move and in the rear areas. Then there are the experiences of civilians – in the provinces, in evacuation to the temporary wartime capital, Kuibyshev, and in Moscow itself. Love affairs, divorces, the problems of acquiring a ration card or a residence permit – they are all here, the tragic and the trivial side by side.

In is all enormously impressive too, but the level is decidedly uneven. And there is so very, very much of everything. One wonders, not for the first time, why Russian authors are so relentlessly committed to fictional gigantism. One cynical explanation is that they are perverted for life because they are paid by the page and not on the basis of sales. A less cynical explanation puts it all down to their wish to emulate Tolstoy’s “War and Peace.” But when Robert Chandler, the workmanlike translator of “Life and Fate,” calls it, in his preface, “the true ‘War and Peace’ of this century,” I incline to cavil, though I can see why he thinks so. For example, Grossman does vie with Tolstoy in embracing so many events and personages of historical importance: Stalin, Hitler, Eichmann and not a few real-life Soviet generals are among his minor characters. But his chronological range is far more restricted than Tolstoy’s. Then again, Tolstoy’s great novel has itself been criticized as loosely shaped. But it does at least have a shape of sorts – more so, anyway, than Grossman’s sprawling work. This book has little in the way of compelling plot line, while samples of narrative skill are all too sparse. A little suspense here, the occasional surprise there, the odd humorous or sarcastic touch: it doesn’t add up to much in the way of vibrancy.

Above all Grossman lacks Tolstoy’s flair for characterization, as do so many other modern Russian fiction writers. Whether we think of the endless minor figures in the novel, introduced so lavishly as to put even “War and Peace” in the shade, or of the handful of major male heroes, or of the comparably featureless Lyudmilas, Yevgenias and Alexandra Vladimirovnas – everywhere we find the inability to breathe full conviction into the printed word. The man can make residence permits, army rations, booze-ups in dugouts, gas chambers and mass graves credible. What a pity, then, that he can’t do the same for human beings. Yes, yes, he does hand out various physical characteristics, a ginger-colored mustache here, a twitching right eye there. But his brain children largely tend to be stillborn.

________________________________________

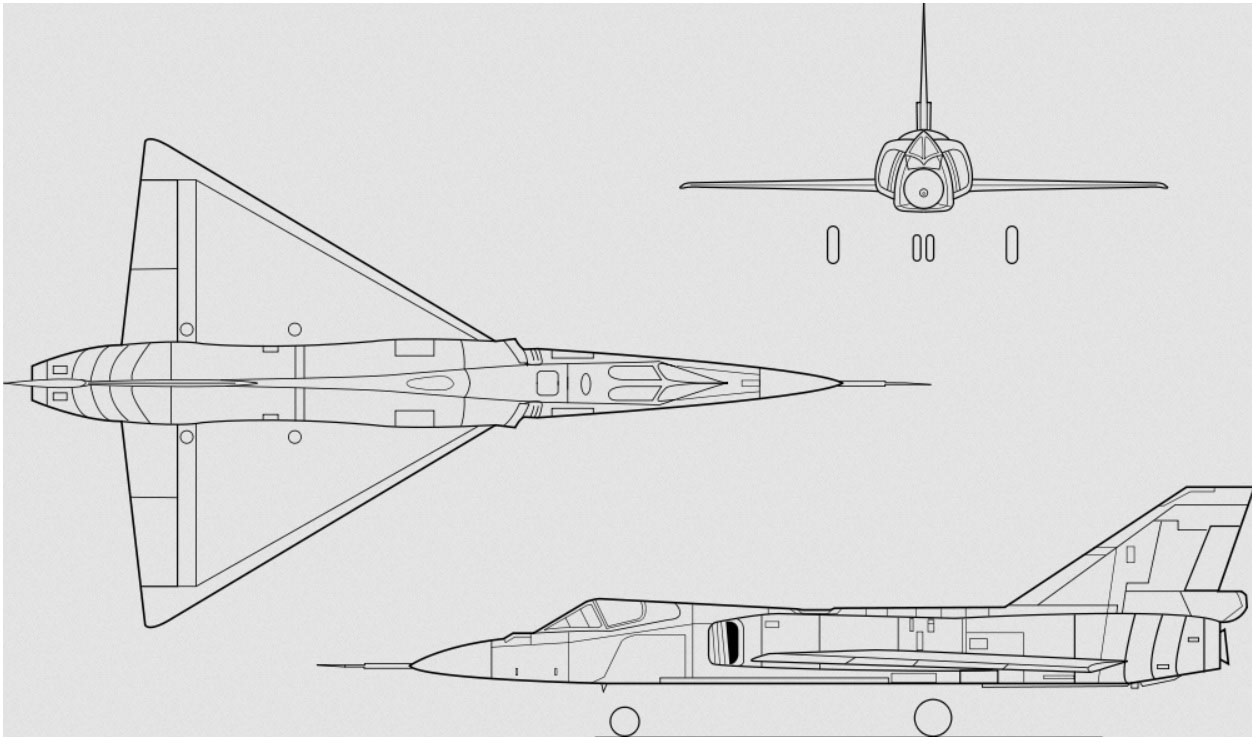

Disposition of Soviet and German forces during Battle of Stalingrad, as an explanatory map in Harper & Row 1987 paperback edition of Life and Fate.

Disposition of Soviet and German forces during Battle of Stalingrad, as an explanatory map in Harper & Row 1987 paperback edition of Life and Fate.

________________________________________

This is true even of the novel’s main character, the nuclear physicist Viktor Shtrum. Here is a politically ambivalent figure given to dropping indiscreet remarks. His star seems ascendant when he makes a crucial discovery in theoretical physics, but he soon becomes the target for an anti-Semitic witch hunt at his institute. Only at the last moment, when he seems firmly marked as concentration camp fodder, is he unexpectedly rescued by one of Stalin’s famous deus ex machina telephone calls. This redeems Shtrum’s position. But it also – more significantly – effects his ideological seduction from the status of political waverer to that of enthusiastic pillar of the scientific establishment. Perhaps Grossman is here apologizing, through his hero, for his own many accommodations with the literary establishment, which so richly rewarded him. In the light of such speculations Shtrum’s dilemmas become considerably more fascinating than Shtrum himself.

________________________________________

But an invisible force was crushing him.

He could feel its weight, its hypnotic power;

it was forcing him to think as it wanted, to write as it dictated.

This force was inside him;

it could dissolve his will and cause his heart to stop beating;

it came between him and his family;

it insinuated itself into his past, into his childhood memories.

He began to feel that he really was untalented and boring,

someone who wore out the people around him with dull chatter.

Even his work seemed to have grown dull,

to be covered with a layer of dust;

the thought of it no longer filled him with light and joy.

Only people who have never felt such a force themselves

can be surprised that others submit to it.

Those who have felt it, on the other hand,

feel astonished that a man can rebel against it even for a moment

– with one sudden word of anger,

one timid gesture of protest.

________________________________________

THANKS are due to Robert Chandler for providing a clear account of the novel’s history. Too often illicit Soviet writings are dumped in front of the Western reader with the bare title, author’s name and translator’s name, and the customary blurb comparing the contents to Tolstoy, Chekhov, Shakespeare or whomever – that is all. But about material emanating from such a fuzzy context we badly need hard information, and we get that kind of information here.

Mr. Chandler’s long labors have made available a work that substantially justifies his own description of it as “the most complete portrait of Stalinist Russia we have or are ever likely to have.” It is, at very least, a significant addition to the great library of smuggled Russian works by Pasternak and his many successors, works written in the Soviet Union but destined almost exclusively for the un-Kremlinized reader.

Everyone Remembered 1937

Scientific research in the country had been discussed by the Central Committee. When Shcherbakov had proposed a reduction in the Academy’s budget, Stalin had shaken his head and said: “No, we’re not talking about making soap. We are not going to economize on the Academy.” Everyone expected a considerable improvement in the position of scientists… A few days later an important botanist was arrested, Chetyerikov the geneticist. There were various rumours about the reason for his arrest… Since the beginning of the war there had been relatively little talk of political arrests. Many people, Viktor among them, thought that they were a thing of the past. Now everyone remembered 1937: the daily roll-call of people arrested during the night, people phoning each other up with the news….

Viktor remembered the names of dozens of people who had left and never returned: Academician Vavilov, Vize, Osip Mandelstam, Babel, Boris Pilnyak, Meyerhold, the bacteriologists Korshunov and Zlatogorov, Professor Pletnyov, Doctor Levin.

Was all this going to begin again? Would one’s heart sink, even after the war, when one heard footsteps or a car horn during the night?

How difficult it was to reconcile such things with the war for freedom!

From “Life and Fate”

Ronald Hingley’s most recent books are “Pasternak,” a biography, and “Nightingale Fever,” a study of four 20th-century Russian poets.

Suggested Readings

Aciman, Alexander, Book Review: Vasily Grossman, the Great Forgotten Soviet Jewish Literary Genius of Exile and Betrayal, Lives Inside Us All, Tablet, October 23, 2017

Capshaw, Ron, The Scroll: The Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee Was Created to Document the Crimes of Nazism Before They Were Murdered by Communists – For the crime of acknowledging Jewish identity, the committee’s members were killed in a Stalinist pogrom, Tablet, November 29, 2018

Epstein, Joseph, The Achievement of Vasily Grossman – Was he the greatest writer of the past century?, Commentary, May, 2019

Eskin, Blake, Book Review: Eyewitness – A collection of Vasily Grossman’s shorter work offers a chance to reassess the Soviet master’s life and legacy. A conversation with Grossman translator Robert Chandler, Tablet, December 8, 2010

Kirsch, Adam, Book Review: No Exit: Life and Fate, Vasily Grossman’s indispensable account of the horrors of Stalinism and the Holocaust, puts Jewishness at the heart of the 20th century, Tablet, November 30, 2011

Taubman, William, Book Review: Life and Fate: A biography of Vasiliy Grossman, the Soviet writer whose masterpiece compared Stalin’s regime to Hitler’s, The New York Times Book Review, p. 16, July 14, 2019

Vapnyar, Lara, Book Review: Dispatches – How World War II turned a Soviet loyalist into a dissident novelist. Plus: An audio interview with the editor of A Writer at War, Tablet, January 30, 2006

Grossman’s Life and Fate to be Serialised by the BBC, at Russian Books

Grossman’s War: Life and Fate, at BBC

Life and Fate: vivid, heartbreaking, illuminating and utterly brilliant, at The Guardian

Life And Fate: probably the best Stalingrad movie so far, at Stalingrad Battle Date

Life and Fate, at Internet Movie Database

The composition shows green-skinned humanoids in seeming battle against huge, levitating, tentacled, purplish organic entities, all of which share an identical body plan. What are these things?

The composition shows green-skinned humanoids in seeming battle against huge, levitating, tentacled, purplish organic entities, all of which share an identical body plan. What are these things?