My parents had a bookcase which held a few hardcovers

My parents had a bookcase which held a few hardcovers

and a library of Pocket Books,

whose flimsy, browning pages would crack if you bent down the corners.

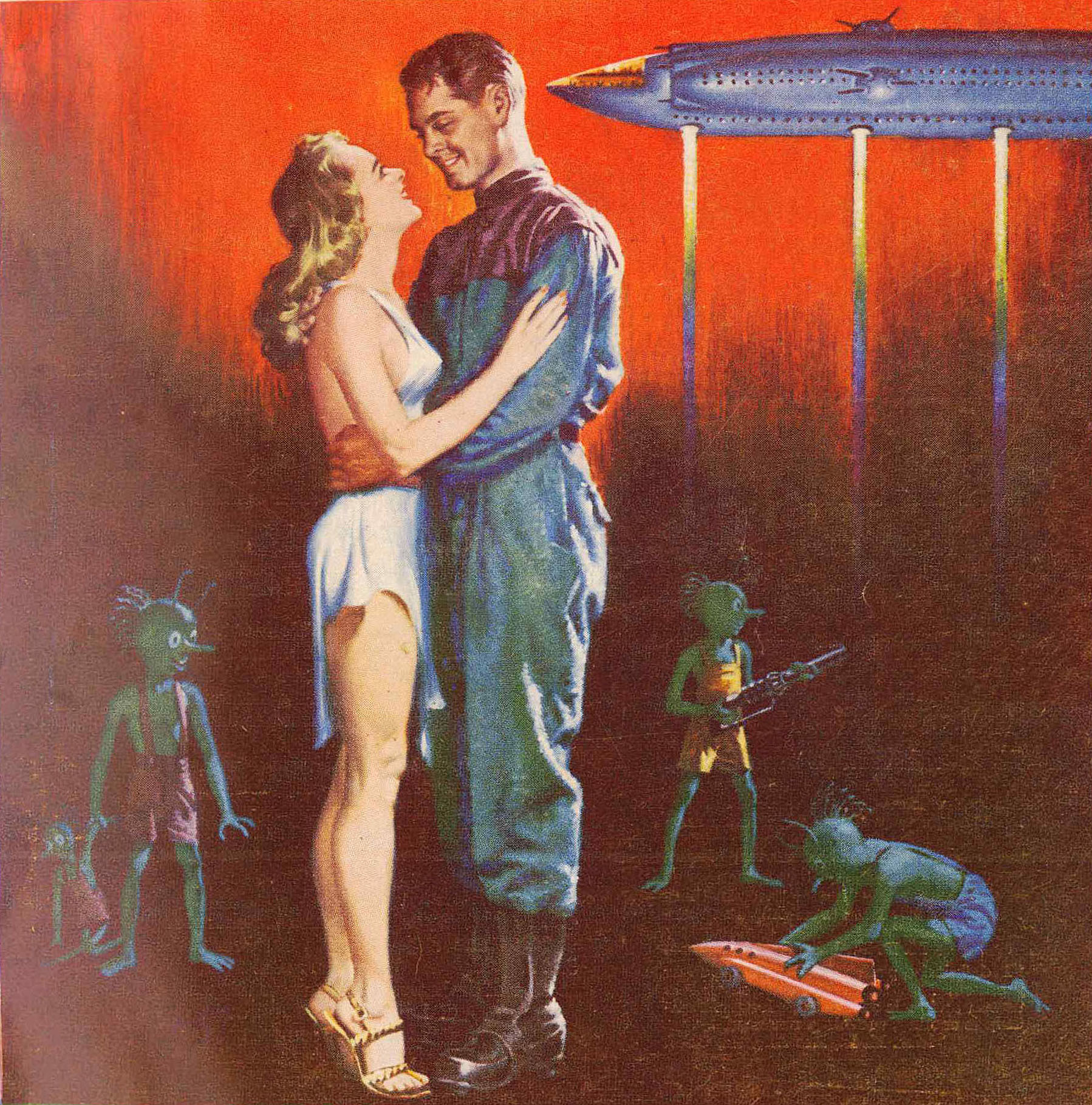

I can still picture those cellophane-peeling covers with their kangaroo logo,

their illustrations of busty, available-looking women

or hard-bodied men

or solemn, sensitive-looking Negroes with titles like

Intruder in the Dust,

Appointment in Samara,

Tobacco Road,

Studs Lonigan,

Strange Fruit,

Good Night, Sweet Prince,

The Great Gatsby,

The Sound and the Fury.

Father brought home all the books, it was his responsibility;

though Mother chafed at everything else in the marriage,

she still permitted him at the same time to be her intellectual mentor.

I have often wondered on what basis he made his selections:

he’d had only one term of night college

(dropping out because he fell asleep in class after a day in the factory),

and I never saw him read book reviews.

He seemed all the same, to have a nose for decent literature.

He was one of those autodidacts of the Depression generation,

for whose guidance the inexpensive editions

of Everyman, Modern Library, and Pocket Books seemed intentionally designed,

out of some bygone assumption that the workingman should

– must

– be educated to the best in human knowledge.

(by Phillip Lopate, from “Samson and Delilah and the Kids”)

______________________________

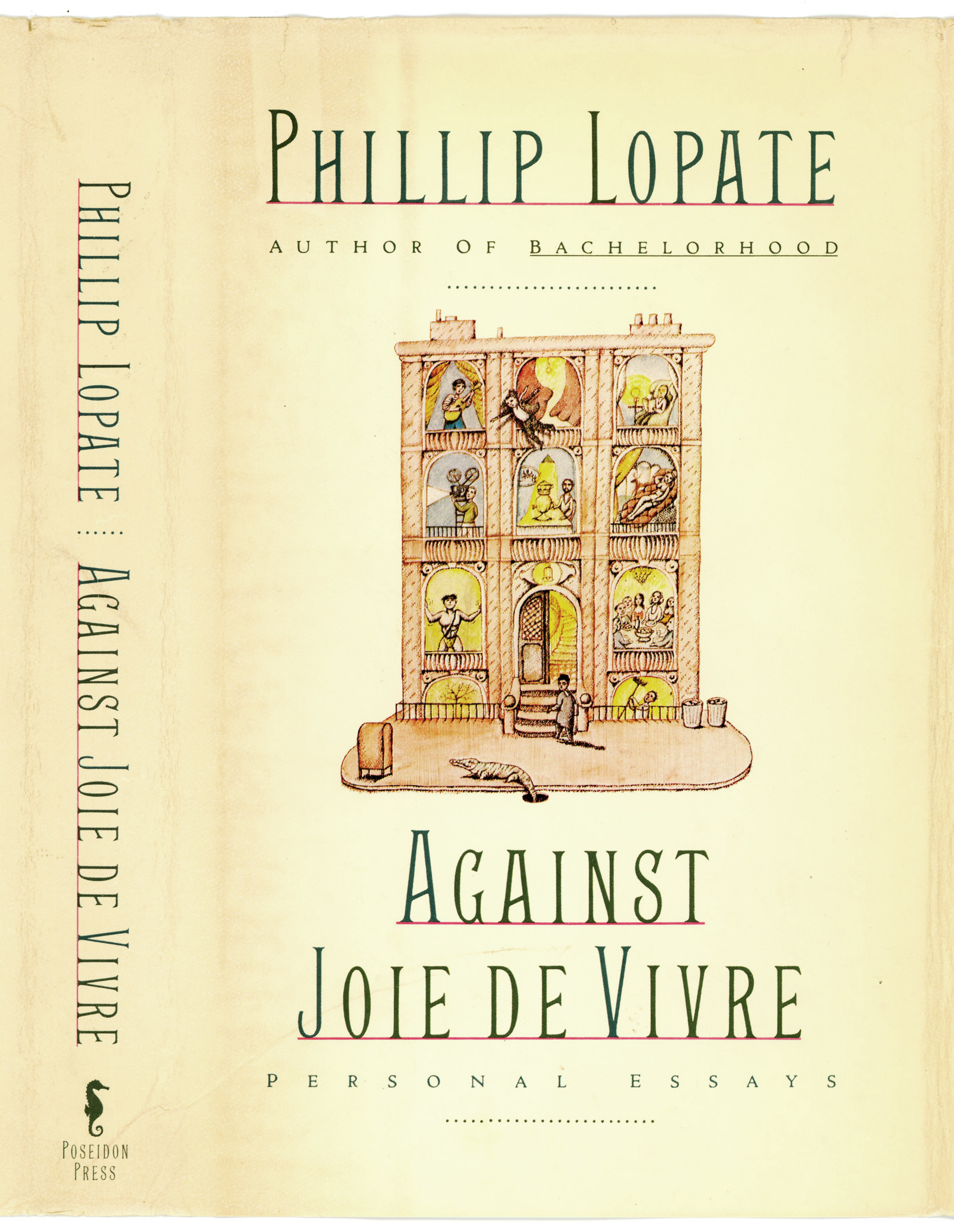

Cover illustration by Peter Sis. The nine (or is it eleven?) vignettes symbolize the central themes of book’s nineteen essays, the titles of which are listed below…

Samson and Delilah and the Kids

Against Joie de Vivre

Art of the Creep

A Nonsmoker with a Smoker

What Happened to the Personal Essay?

II

Never Live Above Your Landlord

Revisionist Nuptials

Anticipation of La Notte: The “Heroic” Age of Moviegoing

Modern Friendships

A Passion for Waiting

III

Chekhov for Children

On Shaving a Beard

Only Make Believe: Some Observations on Architectural Language

Houston Hide-and-Seek

Carlos: Evening in the City of Friends

IV

Upstairs Neighbors

Waiting for the Book to Come Out

Reflections on Subletting

Suicide of a Schoolteacher

______________________________