There are many ways to “illustrate” a story, without literally illustrating the story.

For example, you can depict characters, events, and settings, either literally or symbolically. You can portray physical objects or places; moods and expressions, or, reactions and emotions.

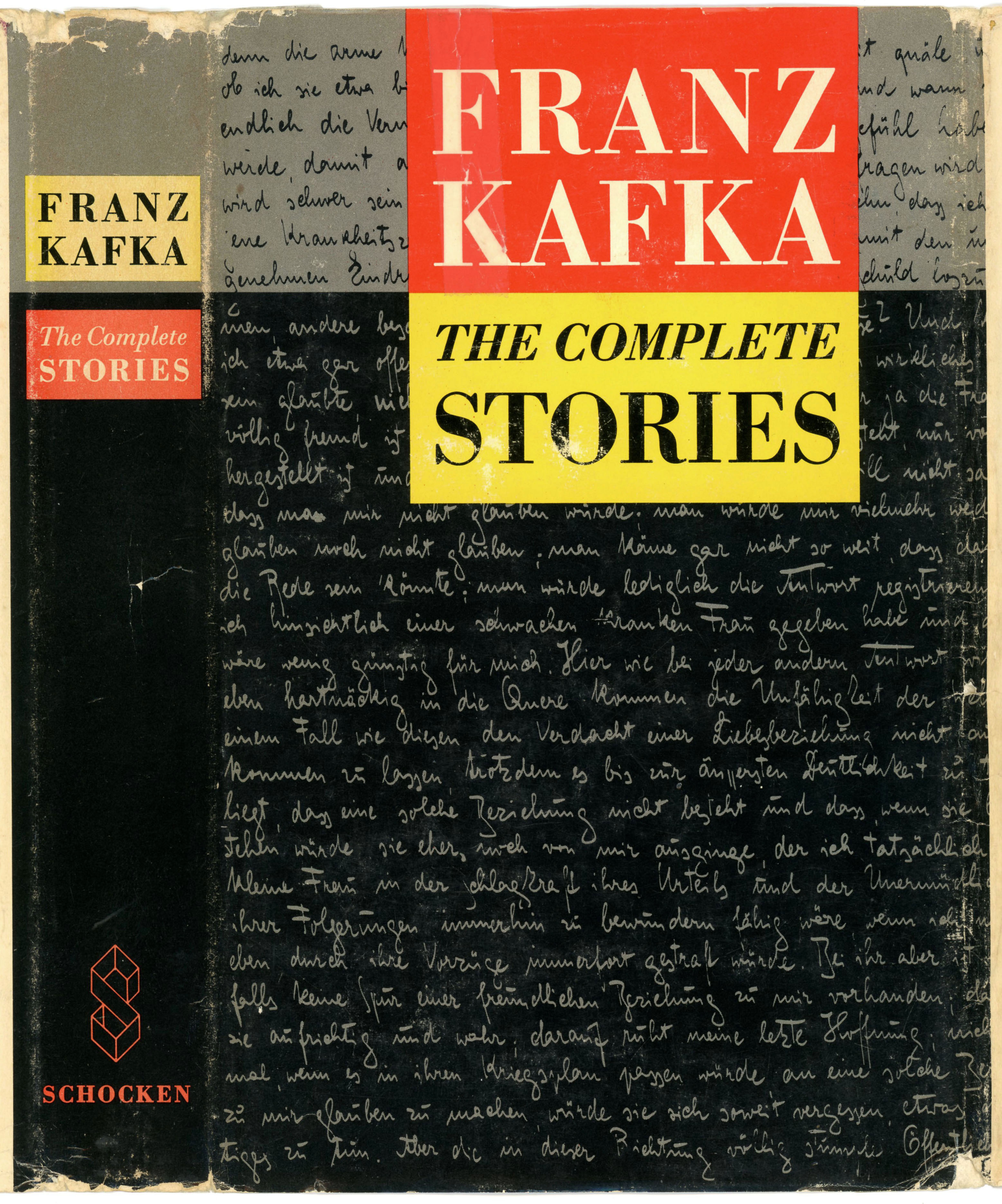

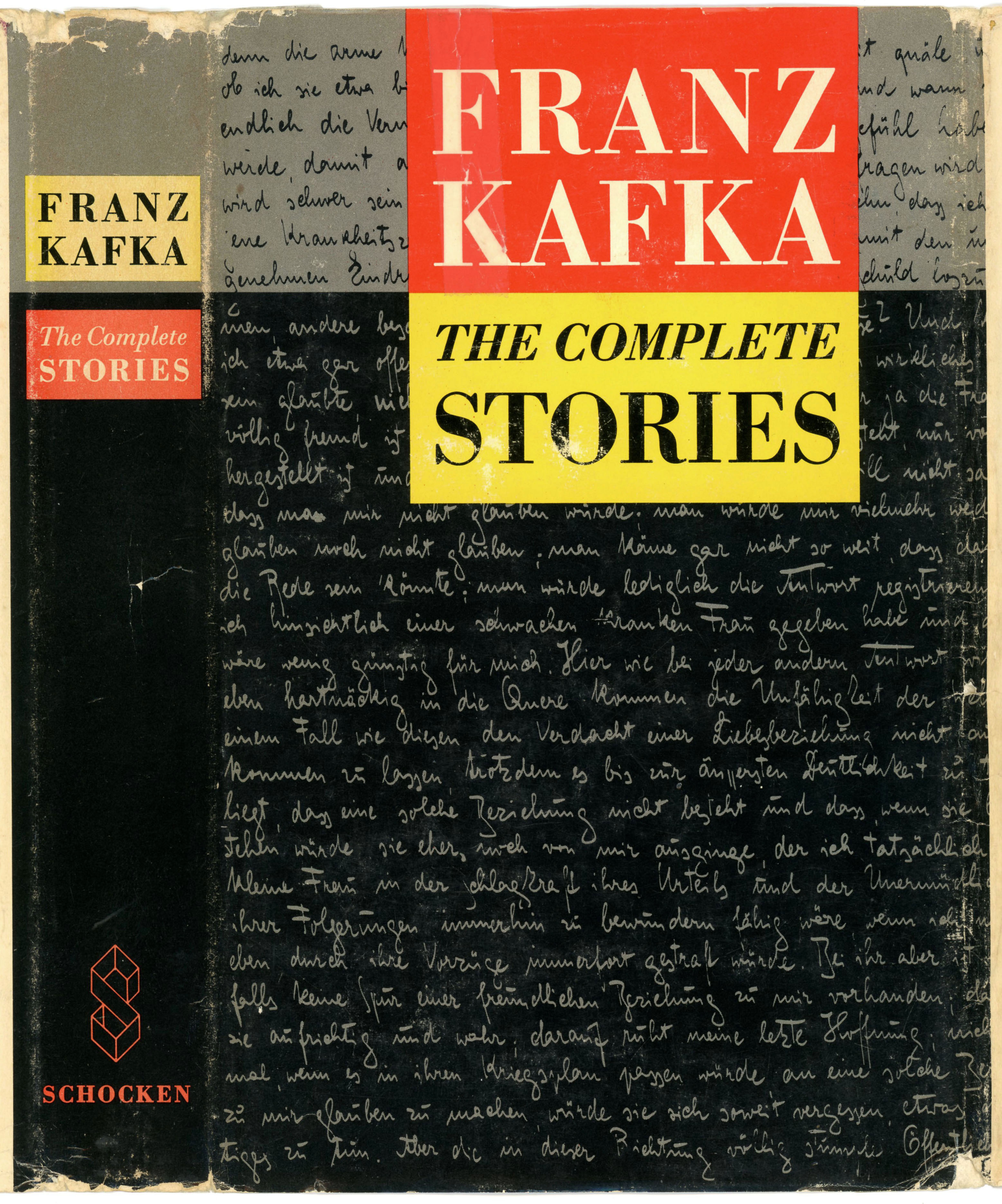

Another way to present an image of a story is by displaying the very text of the story. A nice example of this appeared as the cover of Shocken Books’ 1971 edition of Franz Kafka – The Complete Stories, which was originally published in 1946. The 1971 edition of the book shows a page of the handwritten text of one of Kafka’s stories, though (!) I don’t know the particular story – or perhaps novel – to which the text pertains, and neither the cover flaps nor title page reveal this information. But, for a book cover of a collection of a writer’s writings, Klaus Gemmings’ cover “works”.

As stated on the cover flap, “FOR THE FIRST TIME, all the stories of Franz Kafka – one of the great writers of the twentieth century – are collected here in one comprehensive volume. With the exception of the three novels, the whole of his narrative work is included. The remarkable depth and breadth of his shorter fiction, the full scope of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when the stories are seen as a whole.

As stated on the cover flap, “FOR THE FIRST TIME, all the stories of Franz Kafka – one of the great writers of the twentieth century – are collected here in one comprehensive volume. With the exception of the three novels, the whole of his narrative work is included. The remarkable depth and breadth of his shorter fiction, the full scope of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when the stories are seen as a whole.

The collection offers an astonishing range of insights into the writer’s world: his war of observing and describing reality, the dreamlike events, his symbolism and irony, and his concern with the human condition. The simplicity, precision, and clarity of Kafka’s style are deceptive, and the attentive reader will be aware of the existential abyss opening beneath the seemingly spare surface of a tale.

An irresistible inner force drove Kafka to write: “The tremendous world have in my head. But how free myself and free it without being torn to pieces. And a thousand times rather be torn to pieces than retain it in me or bury it!” For him, writing was both an agonizing and a liberating process: “God does not want me to write, but I – I must write!” Kafka’s work was born from this tragic tension.”

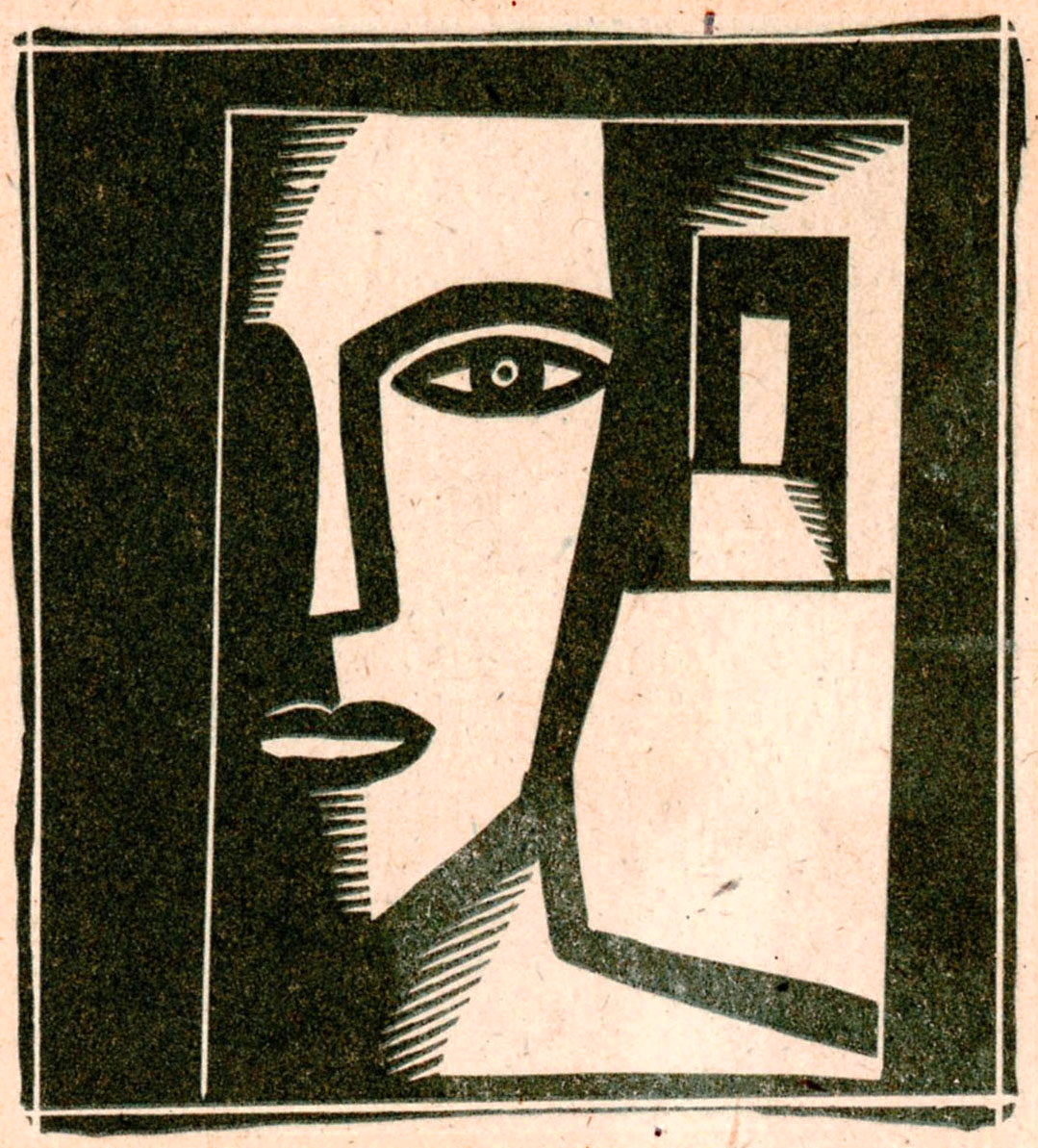

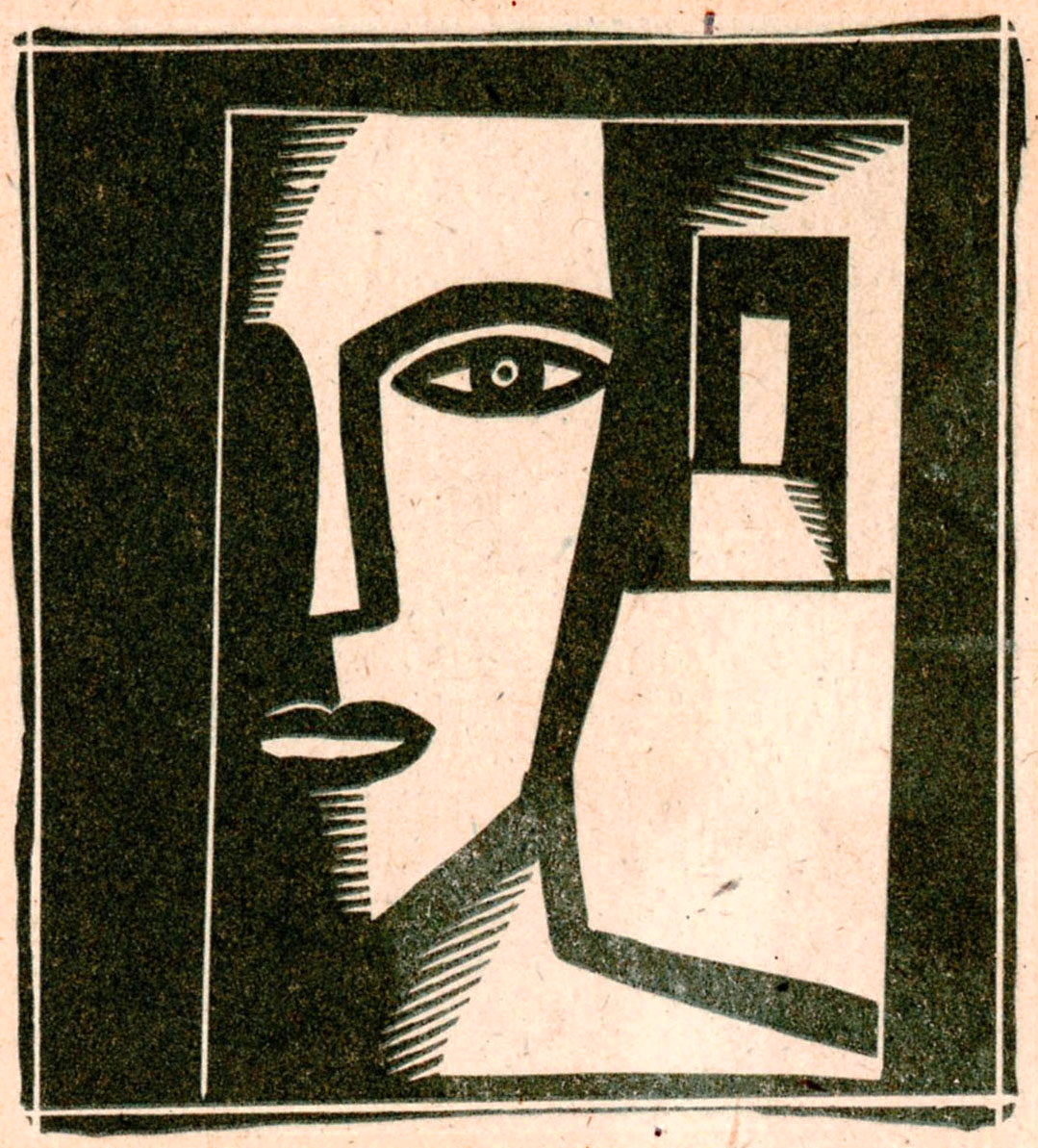

The book’s 1983 softcover edition (with a foreword by John Updike) takes a different approach: Like other compilations of Kafka’s works published by Shocken in the 1980s, the cover displays a small, square-format, untitled, symbolic illustration by Anthony Russo. Perhaps the interpretation of the image is meant to be enigmatic; perhaps left to the reader. If so (I think so), I think the composition of an anonymous man staring through a window – or door? – yes, a door – with two open doors behind him, represents “Before The Law”, the full text of which is given below…

Before The Law

Before The Law

Before the Law stands a doorkeeper.

To this doorkeeper there comes a man from the country and prays for admittance to the Law.

But the doorkeeper says that he cannot grant admittance at the moment.

The man thinks it over and then asks if he will be allowed in later.

“It is possible,” says the doorkeeper, “but not at the moment.”

Since the gate stands open, as usual, and the doorkeeper steps to one side,

the man stoops to peer through the gateway into the interior.

Observing that, the doorkeeper laughs and says:

“If you are so drawn to it, just try to go in despite of my veto.

But take note: I am powerful.

And I am only the least of the doorkeepers.

From hall to hall there is one doorkeeper after another, each more powerful than the last.

The third doorkeeper is already so terrible that even I cannot bear to look at him.”

These are difficulties the man from the country has not expected;

the Law, he thinks, should surely be accessible at all times and to everyone,

but as he now takes a closer look at the doorkeeper in the far corner,

with his big sharp nose and long, thin, black Tartar beard,

he decides that it is better to wait until he gains permission to enter.

The doorkeeper gives him a stool and lets him sit down at one side of the door.

There he sits for days and years.

He makes many attempts to be admitted, and wearies the doorkeeper by his importunity.

He doorkeeper frequently has little interviews with him,

asking him questions about his home and many other things,

but the questions are put indifferently,

as great lords put them, and always finish with the statement that he cannot be let in yet.

The man, who has furnished himself with many things for his journey,

sacrifices all he has, however valuable, to bribe the doorkeeper.

The doorkeeper accepts everything, but always with the remark:

“I am only taking it to keep you from thinking you have omitted anything.”

During these many years the man fixes his attention almost continuously on the doorkeeper.

He forgets the other doorkeepers,

and this first one seems to him the sole obstacle preventing access to the Law.

He curses his bad luck;

in his early years boldly and loudly;

later, as he grows old, he only grumbles to himself.

He becomes childish,

and since in his yearlong contemplation of the doorkeeper

he has come to know even the fleas in his fur collar,

he begs the fleas as well to help him and to change to doorkeeper’s mind.

At length his eyesight begins to fail,

and he does not know whether the world is really darker or whether his eyes are only deceiving him.

Yet in his darkness he is now aware of a radiance

that streams inextinguishably from the gateway of the Law.

Now he has not very long to live.

Before he dies, all his experiences in these long years gather themselves in his head to one point,

a question he has not yet asked the doorkeeper.

He waves him nearer, since he can no longer raise his stiffening body.

The doorkeeper has to bend low toward him,

for the difference in height between them has altered much to the man’s disadvantage.

“What do you want to know now?” asks the doorkeeper; “you are insatiable.”

“Everyone strives to reach the Law,” says the man,

“so how does it happen that for all these many years no one buy myself has ever begged for admittance?”

The doorkeeper recognizes that the man has reached his end,

and, to let his failing senses catch the words, roars in his ear:

“No one else could ever be admitted here, since this gate was made only for you.

I am now going to shut it.”

(Translated by Willa and Edwin Muir)

(Translated by Willa and Edwin Muir)

________________________________________

Here are four other stories by Kafka, the page number of each denoting the softcover edition. In terms of depth (upon depth, upon depth, upon…) each tale is stunning in its own way.

____________________

The Next Village (404)

My grandfather used to say, “Life is astoundingly short.

To me, looking back over it, life seems so foreshortened that I can scarcely understand,

for instance,

how a young man can decide to ride over to the next village without being afraid that –

not to mention accidents –

even the span of a normal happy life may fall far short of the time needed for such a journey.”

(Translated by Willa and Edwin Muir)

Prometheus (432)

There are four legends concerning Prometheus.

According to the first

he was clamped to a rock in the Caucasus for betraying the secrets of the gods to men,

and the gods sent eagles to feed on his liver, which was perpetually renewed.

According to the second

Prometheus, goaded by the pain of the tearing beaks,

pressed himself deeper and deeper into the rock until he became one with it.

According to the third

his treachery was forgotten in the course of thousands of years,

forgotten by the gods, the eagles, forgotten by himself.

According to the fourth

everyone grew weary of the meaningless affair.

The gods grew weary, the eagles grew weary, the wound closed wearily.

There remained the inexplicable mass of rock.

The legend tried to explain the inexplicable.

As it came out of the substratum of truth it had in turn to end in the inexplicable.

(Translated by Willa and Edwin Muir)

A Little Fable (445)

“Alas,” said the mouse, “the world is growing smaller every day.

At the beginning it was so big that I was afraid, I kept running and running,

and I was glad when at last I saw walls far away to the right and left,

but these long walls have narrowed so quickly that I am in the last chamber already,

and there in the corner stands the trap that I must run into.”

“You only need to change your direction,” said the cat,

and ate it up.

(Translated by Willa and Edwin Muir)

The Departure (449)

I ordered my horse to be brought from the stables.

The servant did not understand my orders.

So I went to the stables myself, saddled my horse, and mounted.

In the distance I heard the sound of a trumpet, and I asked the servant what it meant.

He knew nothing and had heard nothing.

At the gate he stopped me and asked, “Where is the master going?”

“I don’t know,” I said, “just out of here, just out of here.

Out of here, nothing else, it’s the only way I can reach my goal.”

“So you know your goal?” he asked.

“Yes,” I replied, “I’ve just told you.

Out of here – that’s my goal.”

(Translated by Tania and James Stern)

______________________________

______________________________