In early 1988, a little over a year after his interview with Primo Levi (published in The New York Times Book Review as “A Man Saved by His Skills” in October of 1986 Philip Roth had an analogous encounter with Aharon Appelfeld at the latter’s Jerusalem home. Illustrated with two images by photographer Micha Bar-Am, Roth’s interview – or was it more accurately deemed a penetrating conversation? – touches upon a multiplicity of topics. These include Appelfeld’s home life in Israel; his literary and sociological perspective of Jewish writers such as Franz Kafka and Bruno Schulz; the relationship of his body of work to the historical experience of the Jewish people – particularly those most assimilated and acculturated to the currents of European society from the late 1800s through the years before the Shoah (epitomized in Badenheim 1939 and Tzili, The Story of A Life); Appelfeld’s life in Israel subsequent to his arrival in the country as a youth after WW II; the “Jewish” perception of both Gentiles and Jews (from vantage points literary, religious, social, and symbolic) in light of the historical experience of the Jewish people before and after the Holocaust. The interview closes with ambivalently positive musings about the “place” of survivors of Shoah in contemporary (well, contemporary in the late 1980s!) Israel.

____________________ ____________________ ____________________

It took me years to draw close to the Jew within me.

I had to get rid of many prejudices within me

and to meet many Jews in order to find myself in them.

Anti-Semitism directed at oneself was an original Jewish creation.

I don’t know of any other nation so flooded with self-criticism.

Even after the Holocaust Jews did not seem blameless in their own eyes.

On the contrary, harsh comments were made by prominent Jews against the victims,

for not protecting themselves and fighting back.

The Jewish ability to internalize any critical and condemnatory remark

and castigate themselves is one of the marvels of human nature.

What has preoccupied me,

and continues to perturb me,

is this anti-Semitism directed at oneself,

an ancient Jewish ailment which,

in modern times,

has taken on various guises.

____________________ ____________________ ____________________

Walking the Way of the Survivor

A Talk With Aharon Appelfeld

By Philip Roth

The New York Times Book Review

February 28, 1988

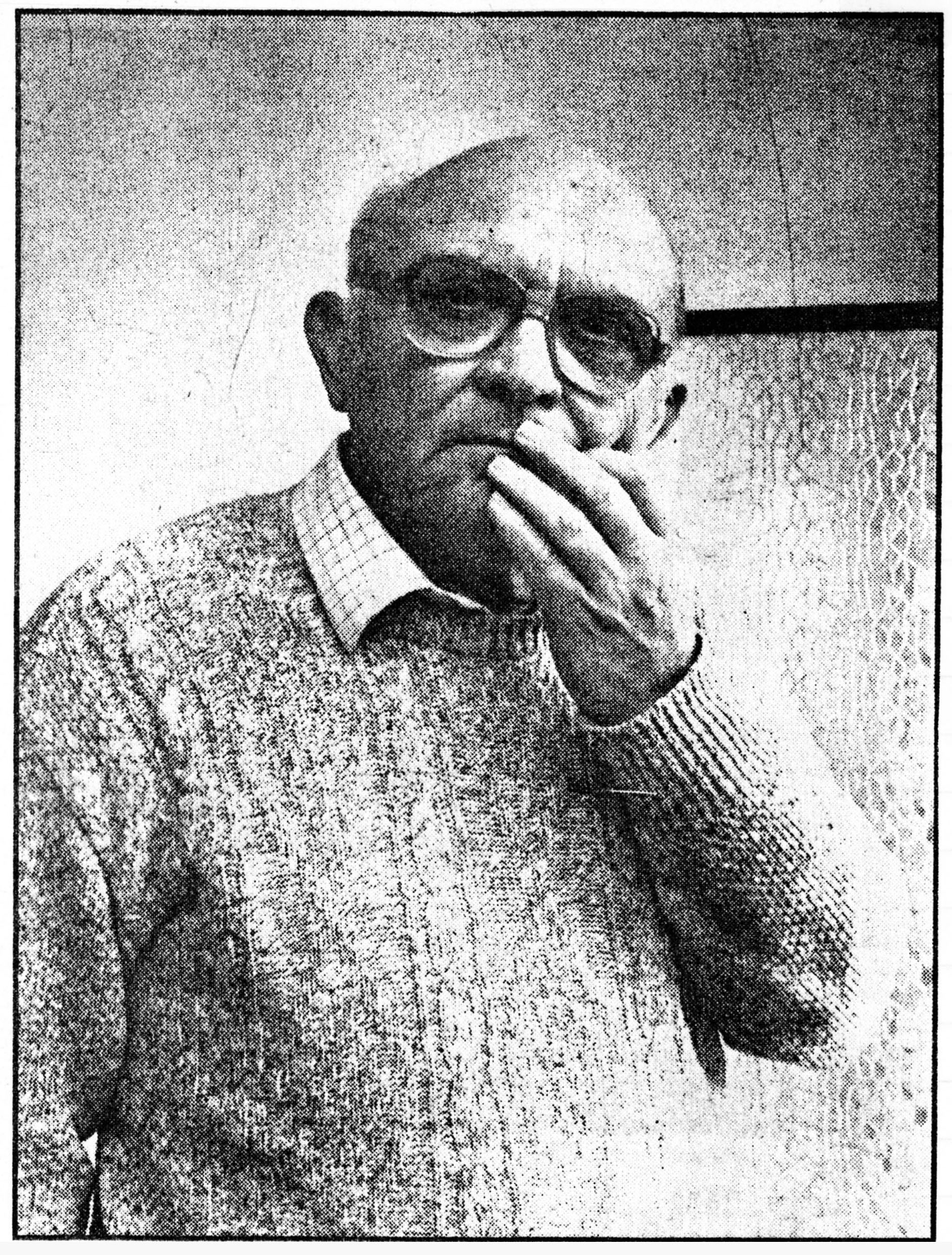

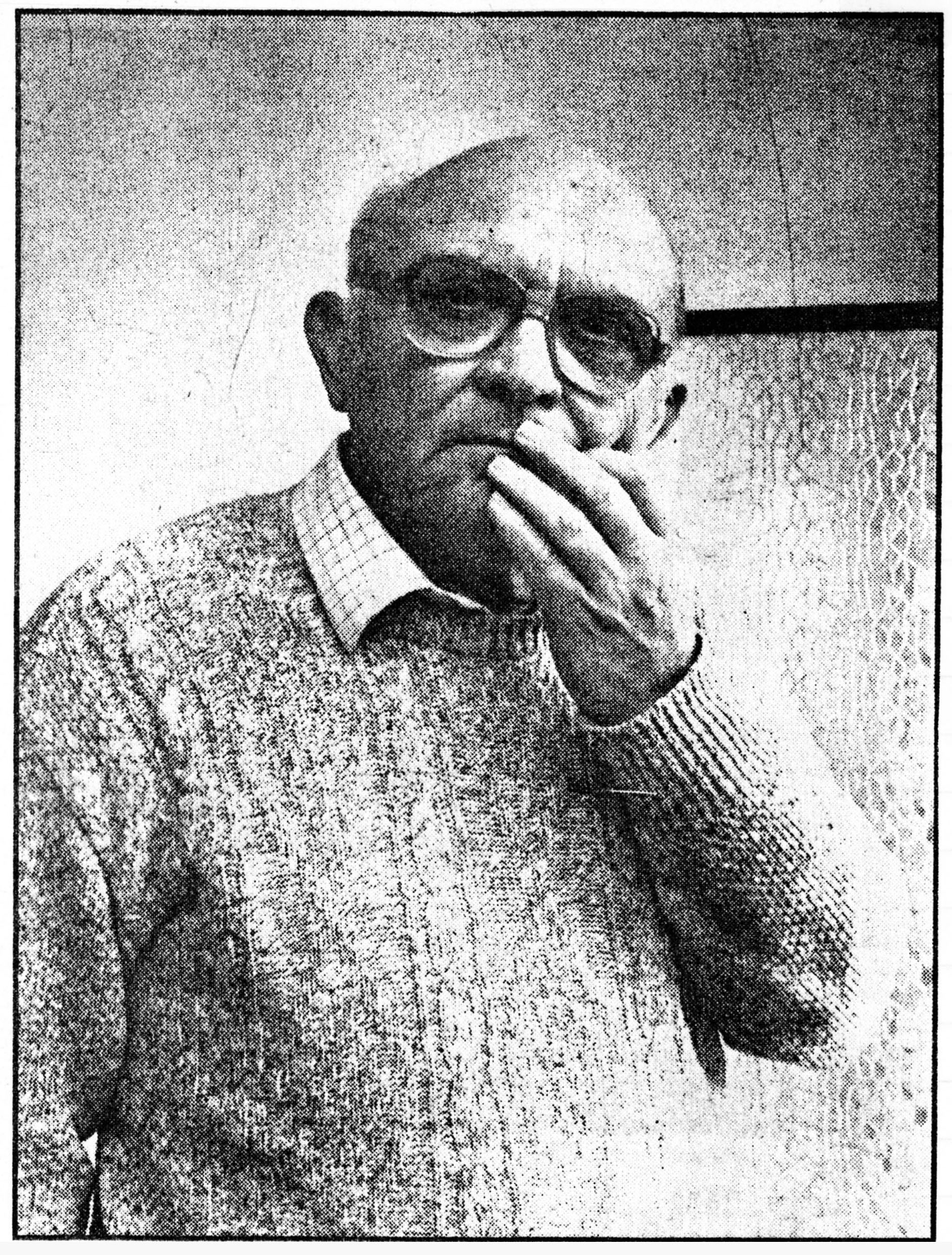

Photograph by Micha Bar-Am

Photograph by Micha Bar-Am

AHARON APPELFELD lives a few miles west of Jerusalem in a mazelike conglomeration of attractive stone dwellings directly next to an “absorption center,” where immigrants are temporarily housed, schooled and prepared for life in their new society. The arduous journey that landed Appelfeld on the beaches of Tel Aviv in 1946, at the age of 14, seems to have fostered an unappeasable fascination with all uprooted souls, and at the local grocery where he and the absorption center residents do their shopping, he will often initiate an impromptu conversation with an Ethiopian, or a Russian, or a Rumanian Jew still dressed for the climate of a country to which he or she will never return.

Photograph by Micha Bar-Am

Photograph by Micha Bar-Am

The living room of the two-story apartment is simply furnished: some comfortable chairs, books in three languages on the shelves, and on the walls impressive adolescent drawings by the Appelfelds’ son Meir, who is now 21 and, since finishing his military duty, has been studying art in London. Yitzak, 18, recently completed high school and is in the first of his three years of compulsory army service. Still at home is 12-year-old Batya, a clever girl with the dark hair and blue eyes of her Argentinian Jewish mother, Appelfeld’s youthful, good-natured wife, Judith. The Appelfelds appear to have created as calm and harmonious a household as any child could hope to grow up in. During the four years that Aharon and I have been friends, I don’t think I’ve ever visited him at home in Mevasseret Zion without remembering that his own childhood – as an escapee from a Nazi work camp, on his own in the primitive wilds of the Ukraine – provides the grimmest possible antithesis to this domestic ideal.

A PORTRAIT photograph that I’ve seen of Aharon Appelfeld, an antique-looking picture taken in Chernovtsy, Bukovina, in 1938, when Aharon was 6, and brought to Palestine by surviving relatives, shows a delicately refined bourgeois child seated alertly on a hobbyhorse and wearing a beautiful sailor suit. You simply cannot imagine this child, only 24 months on, confronting the exigencies of surviving for years as a hunted and parentless little boy in the woods. The keen intelligence is certainly there, but where is the robust cunning, the animalish instinct, the biological tenacity that it took to endure that terrifying adventure?

As much is secreted away in that child as in the writer he’s become. At 55 Aharon is a small, bespectacled, compact man-with a perfectly round face and a perfectly bald head and the playfully thoughtful air of a benign wizard. He’d have no trouble passing for a magician who entertains children at birthday parties by pulling doves out of a hat – it’s easier to associate his gently affable and kindly appearance with that job than with the responsibility by which he seems inescapably propelled: responding, in a string of elusively portentous stories, to the disappearance from Europe – while he was outwitting peasants and foraging in the forests – of just about all the continent’s Jews, his parents among them.

His literary subject is not the Holocaust, however, or even Jewish .persecution. Nor, to my mind, is what he writes simply Jewish fiction or, for that matter, Israeli fiction. Nor, since he is a Jewish citizen of a Jewish state composed largely of immigrants, is his an exile’s fiction. And, despite the European locale of many of his novels and the echoes of Kafka, these books written in the Hebrew language certainly aren’t European fiction. Indeed, all that Appelfeld is not adds up to what he is, and that is a dislocated writer, a deported writer, a dispossessed and uprooted writer. Appelfeld is a displaced writer of displaced fiction, who has made of displacement and disorientation a subject uniquely his own. His sensibility – marked almost at birth by the solitary Wanderings of a little bourgeois boy through an ominous nowhere – appears to have spontaneously generated a style of sparing specificity, of out-of-time progression and thwarted narrative drives, that is an uncanny prose realization of the displaced mentality. As unique as the subject is a voice that originates in a wounded consciousness pitched somewhere between amnesia and memory; and that situates the fiction it narrates midway between parable and history.

Since we met in 1984, Aharon and I have talked together at great length, usually while walking through the streets of London, New York and Jerusalem. I’ve known him over these years as an oracular anecdotalist and a folkloristic enchanter, as a wittily laconic kibitzer and an obsessive dissector of Jewish states of mind – of Jewish aversions, delusions, remembrances and manias. However, as is often the case in friendships between writers, during these peripatetic conversations we had never really touched on each other’s work – that is, hot until last month, when I traveled to Jerusalem to discuss with him the 6 of his 15 published books that are now in English translation.

After our first afternoon together we disencumbered ourselves of an interloping tape recorder and, though I took some notes along the way, mostly we talked as we’ve become accustomed to talking – wandering down city streets or sitting in coffee shops where we’d stop to rest. When finally there seemed to be little left to say, we sat down together and tried to synthesize on paper – I in English, Aharon in Hebrew – the heart of the discussion. Aharon’s answers to my questions have been translated by Jeffrey M. Green.

ROTH: I find echoes in your fiction of two Middle European writers of a previous generation: Bruno Schulz, the Polish Jew who wrote in Polish and was shot and killed at 50 by the Nazis in Drogobych, the heavily Jewish Galician city where he taught high school and lived at home with his family, and Kafka, the Prague Jew who wrote in German and also lived, according to Max Brod, “spellbound in the family circle” for most of his 41 years. Tell me, how pertinent to your imagination do you consider Kafka and Schulz to be?

APPELFELD: I discovered Kafka here in Israel during the 1950s, and as a writer he was close to me from my first contact. He spoke to me in my mother tongue, German, not the German of the Germans but the German of the Hapsburg Empire, of Vienna, Prague and Chernovtsy, with its special tone, which, by the way, the Jews worked hard to create.

To my surprise he spoke to me not only in my mother tongue but also in another language which I knew intimately, the language of the absurd. I knew what he was talking about. It wasn’t a secret language for me and I didn’t need any explications. I had come from the camps and the forests, from a world that embodied the absurd, and nothing in that world was foreign to me. What was surprising was this: how could a man who had never been there know so much, in precise detail, about that world?

Other surprising discoveries followed. Behind the mask of placelessness and homelessness in his work, stood a Jewish man, like me, from a half-assimilated family, whose Jewish values had lost their content, and whose inner space was barren and haunted. The marvelous thing is that the barrenness brought him not to self-denial or self-hatred but rather to a kind of tense curiosity about every Jewish phenomenon, especially the Jews of Eastern Europe, the Yiddish language, the Yiddish theater, Hasidism, Zionism and even the idea of moving to Mandate Palestine. This is the Kafka of his journals, which are no less gripping than his works.

Kafka emerges from an inner world and tries to get some grip on reality, and I came from a world of detailed, empirical reality, the camps and the forests. My real world was far beyond the power of imagination, and my task as an artist was not to develop my imagination but to restrain it, and even then it seemed impossible to me, because everything was so unbelievable that one seemed oneself to be fictional

At first I tried to run away from myself and from my memories, to live a life that was not my own and to write about a life that was not my own. But a hidden feeling told me that I was not allowed to flee from myself, and that if I denied the experience of my childhood in the Holocaust, I would be spiritually deformed. Only when I reached the age of 30 did I feel the freedom to deal as an artist with those experiences.

To my regret, I came to Bruno Schulz’s work years too late, after my literary approach was rather well formed. I felt and still feel a great affinity with his writing, but not the same affinity I feel with Kafka.

ROTH: In your books, there’s no news from the public realm that might serve as a warning to an Appelfeld victim, nor is the victim’s impending doom presented as part of a European catastrophe. The historical focus is supplied by the reader, who understands, as the victims cannot, the magnitude of the enveloping evil. Your reticence as a historian, when combined with the historical perspective of a knowing reader, accounts for the peculiar impact your work has – for the power that emanates from stories that are told through such very modest means. Also, dehistoricizing the events and blurring the background, you probably approximate the disorientation felt by people who were unaware that they were on the brink of a cataclysm.

It’s occurred to me that the perspective of the adults in your fiction resembles in its limitations the viewpoint of a child, who, of course, has no historical calendar in which to place unfolding events and no intellectual means of penetrating their meaning. I wonder if your own consciousness as a child at the edge of the Holocaust isn’t mirrored in the simplicity with which the imminent horror is perceived in your novels.

APPELFELD: You’re right. In “Badenheim 1939” I completely ignored the historical explanation. I assumed that the historical facts were known to readers and that they would fill in what was missing. You’re also correct, it seems to me, in assuming that my description of the Second World War has something in it of a child’s vision. Historical explanations, however, have been alien to me ever since I became aware of myself as an artist. And the Jewish experience in the Second World War was not “historical.” We came in contact with archaic mythical forces, a kind of dark subconscious the meaning of which we did not know, nor do we know it to this day. This world appears to be rational (with trains, departure times, stations and engineers), but in fact these were journeys of the imagination, lies and ruses, which only deep, irrational drives could have invented. I didn’t understand, nor do I yet understand, the motives of the murderers.

I was a victim, and I try to understand the victim. That is a broad, complicated expanse of life that I’ve been trying to deal with for 30 years now. I haven’t idealized the victims. I don’t think that in “Badenheim 1939” there’s any idealization either. By the way, Badenheim is a rather real place, and spas like that were scattered all over Europe, shockingly petit bourgeois and idiotic in their formalities. Even as a child I saw how ridiculous they were.

It is generally agreed, to this day, that Jews are deft, cunning and sophisticated creatures, with the wisdom of the world stored up in them. But isn’t it fascinating to see how easy it was to fool the Jews? With the simplest, almost childish tricks they were gathered up in ghettos, starved for months, encouraged with false hopes and finally sent to their death by train. That ingenuousness stood before my eyes while I was writing “Badenheim.” In that ingenuousness I found a kind of distillation of humanity. Their blindness and deafness, their obsessive preoccupation with themselves is an integral part of their ingenuousness. The murderers were practical, and they knew just what they wanted. The ingenuous person is always a shlimazl, a clownish victim of misfortune, never hearing the danger signals in time, getting mixed up, tangled up and finally falling in the trap. Those weaknesses charmed me. I fell in love with them. The myth that the Jews run the world with their machinations turned out to be somewhat exaggerated.

ROTH: Of all your translated books, “Tzili” depicts the harshest reality and the most extreme form of suffering Tzili, the simplest child of a poor Jewish family, is left alone when her family flees the Nazi invasion. The novel recounts her horrendous adventures in surviving and her excruciating loneliness among the brutal peasants for whom she works. The book strikes me as a counterpart to Jerzy Kosinski’s “Painted Bird.” Though less grotesque, “Tzili” portrays a fearful child in a world even bleaker and more barren than Kosinski’s, a child moving in isolation through a landscape as uncongenial to human life as any in Beckett’s “Molloy.”

As a boy you wandered alone like Tzili after your escape, at age 8, from the camp. I’ve been wondering why, when you came to transform your own life in an unknown place, hiding out among the hostile peasants, you decided to imagine a girl as the survivor of this ordeal. And did it occur to you ever not to fictionalize this material but to present your experiences as you remember them, to write a survivor’s tale as direct, say, as Primo Levi’s depiction of his Auschwitz incarceration?

APPELFELD: I have never written about things as they happened. All my works are indeed chapters from my most personal experience, but nevertheless they are not “the story of my life.” The things that happened to me in my life have already happened, they are already formed, and time has kneaded them and given them shape. To write things as they happened means to enslave oneself to memory, which is only a minor element in the creative process. To my mind, to create means to order, sort out and choose the words and the pace that fit the work. The materials are indeed materials from one’s life, but, ultimately, the creation is an independent creature.

I tried several times to write “the story of my life” in the woods after I ran away from the camp. But all my efforts were in vain. I wanted to be faithful to reality and to what really happened. But the chronicle that emerged proved to be a weak scaffolding. The result was rather meager, an unconvincing imaginary tale. The things that are most true are easily falsified.

Reality, as you know, is always stronger than the human imagination. Not only that, reality can permit itself to be unbelievable, inexplicable, out of all proportion. The created work, to my regret, cannot permit itself all that.

The reality of the Holocaust surpassed any imagination. If I remained true to the facts, no one would believe me. But the moment I chose a girl, a little older than I was at that time, I removed “the story of my life” from the mighty grip of memory and gave it over to the creative laboratory. There memory is not the only proprietor. There one needs a causal explanation, a thread to tie things together. The exceptional is permissible only if it is part of an overall structure and contributes to its understanding. I had to remove those parts which were unbelievable from “the story of my life” and present a more credible version.

When I wrote “Tzili” I was about 40 years old. At that time I was interested in the possibilities of naiveness in art. Can there be a naive modern art? It seemed to me that without the naivete still found among children and old people and, to some extent, in ourselves, the work of art would be flawed. I tried to correct that flaw. God knows how successful I was.

ROTH: “Badenheim 1939” has been called fablelike, dreamlike, nightmarish and so on. None of these descriptions makes the book less vexing to me. The reader is asked, pointedly I think, to understand the transformation of a pleasant Austrian resort for Jews into a grim staging area for Jewish “relocation” to Poland as being somehow analogous to events preceding Hitler’s Holocaust. At the same time your vision of Badenheim and its Jewish inhabitants is almost impulsively antic and indifferent to matters of causality. It isn’t that a menacing situation develops, as it frequently does in life, without warning or logic, but that about these events you are laconic, I think, to a point of unrewarding inscrutability. Do you mind addressing my difficulties with this highly praised novel, which is perhaps your most famous book in America? What is the relation between the fictional world of “Badenheim” and historical reality?

APPELFELD: Rather clear childhood memories underlie “Badenheim 1939.” Every summer we, like all the other petit bourgeois families, would set out for a resort. Every summer we tried to find a restful place, where people didn’t gossip in the corridors, didn’t confess to one another in corners, didn’t interfere with you, and, of course, didn’t speak Yiddish. But every summer, as though we were being spited, we were once again surrounded by Jews, and that left a bad taste in my parents’ mouths, and no small amount of anger.

Many years after the Holocaust, when I came to retrace my childhood from before the Holocaust, I saw that these resorts occupied a particular place in my memories. Many faces and bodily twitches came back to life. It turned out that the grotesque was etched in no less than the tragic. Walks in the woods and the elaborate meals brought people together in Badenheim – to speak to one another and to confess to one another. People permitted themselves not only to dress extravagantly but also to speak freely, sometimes picturesquely. Husbands occasionally lost their lovely wives, and from time to time a shot would ring out in the evening, a sharp sign of disappointed love. Of course I could arrange these precious scraps of life to stand on their own artistically. But what was I to do? Every time I tried to reconstruct those forgotten resorts, I had visions of the trains and the camps, and my most hidden childhood memories were spotted with the soot from the trains.

Fate was already hidden within those people like a mortal illness. Assimilated Jews built a structure of humanistic values and looked out on the world from it. They were certain they were no longer Jews, and that what applied to “the Jews” did not apply to them. That strange assurance made them into blind or half-blind creatures. I have always loved assimilated Jews, because that was where the Jewish character, and also, perhaps, Jewish fate, was concentrated with greatest force.

ROTH: Living in this society you are bombarded by news and political disputation. Yet, as a novelist you have by and large pushed aside the Israeli daily turbulence to contemplate markedly different, Jewish predicaments. What does this turbulence mean to a novelist like yourself? How does being a citizen of this self-revealing, self-asserting, self-challenging, self-legendizing society affect your writing life? Does the news-producing reality ever tempt your imagination?

APPELFELD: Your question touches on a matter which is very important to me. True, Israel is full of drama from morning to night, and there are people who are overcome by that drama to the point of inebriation. This frenetic activity isn’t only the result of pressure from the outside. Jewish restlessness contributes its part. Everything is buzzing here, and dense; there’s a lot of talk, the controversies rage. The Jewish shtetl has not disappeared.

At one time there was a strong anti-Diaspora tendency here, a recoiling from anything Jewish. Today things have changed a bit, though this country is restless and tangled up in itself, living with ups and downs. Today we have redemption, tomorrow darkness. Writers are also immersed in this tangle. The occupied territories, for example, are not only a political issue but also a literary matter.

I came here in 1946, still a boy, but burdened with life and suffering. In the daytime I worked on kibbutz farms, and at night I studied Hebrew. For many years I wandered about this feverish country, lost and lacking any orientation. I was looking for myself and for the faces of my parents, who had been lost in the Holocaust. During the 1940s one had a feeling that one was being reborn here as a Jew, and one would therefore turn out to be quite a wonder. Every Utopian view produces that kind of atmosphere. Let’s not forget that this was after the Holocaust. To be strong was not merely a matter of ideology. “Never again like sheep to the slaughter” thundered from loudspeakers at every corner. I very much wished to fit into that great activity and take part in the adventure of the birth of a new nation. Naively I believed that action would silence my memories, and I would flourish like the natives, free of the Jewish nightmare, but what could I do? The need, you might say the necessity, to be faithful to my self and to my childhood memories made me a distant, contemplative person. My contemplation brought me back to the region where I was born and where my parents’ home stood. That is my spiritual history, and it is from there that I spin the threads.

Artistically speaking, settling back there has given me an anchorage and a perspective. I’m not obligated to rush out to meet current events and interpret them immediately. Daily events do indeed knock on every door, but they know that I don’t let such agitated guests into my house.

ROTH: In “To the Land of the Cattails,” a Jewish woman and her grown son, the offspring of a gentile father, are journeying back to the remote Ruthenian countryside where she was born. It’s the summer of 1938. The closer they get to her home the more menacing is the threat of gentile violence. The mother says to her son, “They are many, and we are few.” Then you write: “The word goy rose up from within her. She smiled as if hearing a distant memory. Her father would sometimes, though only occasionally, use that word to indicate hopeless obtuseness.”

The gentile with whom the Jews of your books seem to share their world is usually the embodiment of hopeless obtuseness and of menacing, primitive social behavior – the goy as drunkard, wife-beater, as the coarse, brutal semi-savage who is “not in control of himself.” Though obviously there’s more to be said about the non-Jewish world in those provinces where your books are set – and also about the capacity of Jews, in their own world, to be obtuse and primitive, too – even a non-Jewish European would have to recognize that the power of this image over the Jewish imagination is rooted in real experience. Alternatively the goy is pictured as an “earthy soul … overflowing with health.” Enviable health. As the mother in “Cattails” says of her half-gentile son, “He’s not nervous like me. Other, quiet blood flows in his veins.”

I’d say that it’s impossible to know anything really about the Jewish imagination without investigating the place that the goy has occupied in the folk mythology that’s been exploited, in America, at one level by comedians like Lenny Bruce and Jackie Mason and, at quite another level, by Jewish novelists. American fiction’s most single-minded portrait of the goy is in “The Assistant” by Bernard Malamud. The goy is Frank Alpine, the down-and-out thief who robs the failing grocery store of the Jew, Bober, later attempts to rape Bober’s studious daughter, and eventually, in a conversion to Bober’s brand of suffering Judaism, symbolically renounces goyish savagery. The New York Jewish hero of Saul Bellow’s second novel, “The Victim,” is plagued by an alcoholic gentile misfit named Allbee, who is no less of a bum and a drifter than Alpine, even if his assault on Leventhal’s hard-won composure is intellectually more urbane. The most imposing gentile in all of Bellow’s work, however, is Henderson – the self-exploring rain king who, to restore his psychic health, takes his blunted instincts off to Africa. For Bellow no less than for Appelfeld, the truly “earthy soul” is not the Jew, nor is the search to retrieve primitive energies portrayed as the-quest of a Jew. For Bellow no less than for Appelfeld, and, astonishingly, for Mailer no less than for Appelfeld – we all know that in Mailer when a man is a sadistic sexual aggressor his name is Sergius O’Shaugnessy, when he is a wife-killer his name is Stephen Rojack, and when he is a menacing murderer he isn’t Lepke Buchalter or Gurrah Shapiro, he’s Gary Gilmore.

APPELFELD: The place of the non-Jew in Jewish imagination is a complex affair growing out of generations of Jewish fear. Which of us dares to take up the burden of explanation? I will hazard only a few words, something from my personal experience.

I said fear, but the fear wasn’t uniform, and it wasn’t of all Gentiles. In fact, there was a sort of envy of the non-Jew hidden in the heart of the modern Jew. The non-Jew was frequently viewed in the Jewish imagination as a liberated creature without ancient beliefs or social obligations who lived a natural life on his own soil. The Holocaust, of course, altered somewhat the course of the Jewish imagination. In place of envy came suspicion. Those feelings which had walked in the open descended to the underground.

Is there some stereotype of the non-Jew in the Jewish soul? It exists, and it is frequently embodied in the word goy, but that is an undeveloped stereotype. The Jews have had imposed on them too many moral and religious strictures to express such feelings utterly without restraint. Among the Jews there was never the confidence to express verbally the depths of hostility they may well have felt. They were, for good or bad, too rational. What hostility they permitted themselves to feel was, paradoxically, directed at themselves.

What has preoccupied me, and continues to perturb me, is this anti-Semitism directed at oneself, an ancient Jewish ailment which, in modern times, has taken on various guises. I grew up in an assimilated Jewish home where German was treasured. German was considered not only a language but also a culture, and the attitude toward German culture was virtually religious. All around us lived masses of Jews who spoke Yiddish, but in our house Yiddish was absolutely forbidden. I grew up with the feeling that anything Jewish was blemished. From my earliest childhood my gaze was directed at the beauty of the non-Jews. They were blond and tall and behaved naturally. They were cultured, and when they didn’t behave in a cultured fashion, at least they behaved naturally.

Our housemaid illustrated that theory well. She was pretty and buxom, and I was attached to her. She was in my eyes, the eyes of a child, nature itself, and when she ran off with my mother’s jewelry, I saw that as no more than a forgivable mistake.

From my earliest youth I was drawn to non-Jews. They fascinated me with their strangeness, their height, their aloofness. Yet the Jews seemed strange to me too. It took years to understand how much my parents had internalized ail the evil they attributed to the Jew, and, through them, I did so too. A hard kernel of revulsion was planted within each of us.

The change took place in me when we were uprooted from our house and driven into the ghettos. Then I noticed that all the doors and windows of our non-Jewish neighbors were suddenly shut, and we walked alone in the empty streets. None of our many neighbors, with whom we had connections, was at the window when we dragged along our suitcases. I said “the change,” and that isn’t the entire truth. I was 8 years old then, and the whole world seemed like a nightmare to me. Afterward too, when I was separated from my parents, I didn’t know why. All during the war I wandered among the Ukrainian villages, keeping my hidden secret my Jewishness. Fortunately for me I was blond and didn’t arouse suspicion.

It took me years to draw close to the Jew within me. I had to get rid of many prejudices within me and to meet many Jews in order to find myself in them. Anti-Semitism directed at oneself was an original Jewish creation. I don’t know of any other nation so flooded with self-criticism. Even after the Holocaust Jews did not seem blameless in their own eyes. On the contrary, harsh comments were made by prominent Jews against the victims, for not protecting themselves and fighting back. The Jewish ability to internalize any critical and condemnatory remark and castigate themselves is one of the marvels of human nature.

The feeling of guilt has settled and taken refuge among all the Jews who want to reform the world, the various kinds of socialists, anarchists, but mainly among Jewish artists. Day and night the flame of that feeling produces dread, sensitivity, self-criticism and sometimes self-destruction. In short, it isn’t a particularly glorious feeling. Only one thing may be said in its favor: it harms no one except those afflicted with it.

ROTH: In “The Immortal Bartfuss,” your newly translated novel, Bartfuss asks “irreverently” of his dying mistress’s ex-husband, “What have we Holocaust survivors done? Has our great experience changed us at all?” This is the question with which the novel somehow engages itself on virtually every page. We sense in Bartfuss’s lonely longing and regret, in his baffled effort to overcome his own remoteness, in his avidity for human contact, in his mute wanderings along the Israeli coast and ha enigmatic encounters in dirty cares, the agony that life can become in the wake of a great disaster. Of the Jewish survivors who wind up smuggling and black-marketeering in Italy directly after the war, you write, “No one knew what to do with the lives that had been saved.”

My last question, growing out of your preoccupation in “The Immortal Bartfuss,” is, perhaps, preposterously comprehensive, but think about it please, and reply as you choose. From what you observed as a homeless youngster wandering in Europe after the war, and from what you’ve learned during four decades in Israel, do you discern distinguishing patterns in the experience of those whose lives were saved? What have the Holocaust survivors done and in what ways were they ineluctably changed?

APPELFELD: True, that is the painful point of my latest book indirectly I tried to answer your question there. Now I’ll try to expand somewhat The Holocaust belongs to the type of enormous experience which reduces one to silence. Any utterance, any statement any “answer” is tiny, meaningless and occasionally ridiculous. Even the greatest of answers seems petty.

With your permission, two examples. The first is Zionism, Without doubt life in Israel gives the survivors not only a place of refuge but also a feeling that the entire world is not evil. Though the tree has been chopped down, the root has not withered despite everything we continue living. Yet that satisfaction cannot take away the survivor’s feeling that he or she must do something with this life that was saved. The survivors have undergone experiences that no one else has undergone, and others expect some message from them, some key to understanding the human world – a human example. But they, of course, cannot begin to fulfill the great tasks imposed upon them, so theirs are clandestine lives of flight and hiding. The trouble is that no more hiding places are available. One has a feeling of guilt that grows from year to year and becomes, as in Kafka, an accusation. The wound is too deep and bandages won’t help. Not even a bandage such as the Jewish state.

The second example is the religious stance. Paradoxically, as a gesture toward their murdered parents, not a few survivors have adopted religious faith. I know what inner struggles that paradoxical stance entails, and I respect it. But that stance is born of despair. I won’t deny the truth of despair. But it’s a suffocating position, a kind of Jewish monasticism and indirect self-punishment.

My book offers its survivor neither Zionist nor religious consolation. The survivor, Bartfuss, has swallowed the Holocaust whole, and he walks about with it in all his limbs. He drinks the “black milk” of the poet Paul Celan, morning, noon and night. He has no advantage over anyone else, but he still hasn’t lost his human face. That isn’t a great deal, but it’s something?

Philip Roth’s autobiographical work, “The Facts,” will be published in September.

Some References

Aharon Appelfeld, at Wikipedia

Philip M. Roth, at Wikipedia

The Philip Roth Society

Philip Roth, at Open Library

Guide to the Jerome Perzigian Collection of Philip Roth 1958-1987, at The University of Chicago Library

Micha Bar-Am, at Wikipedia