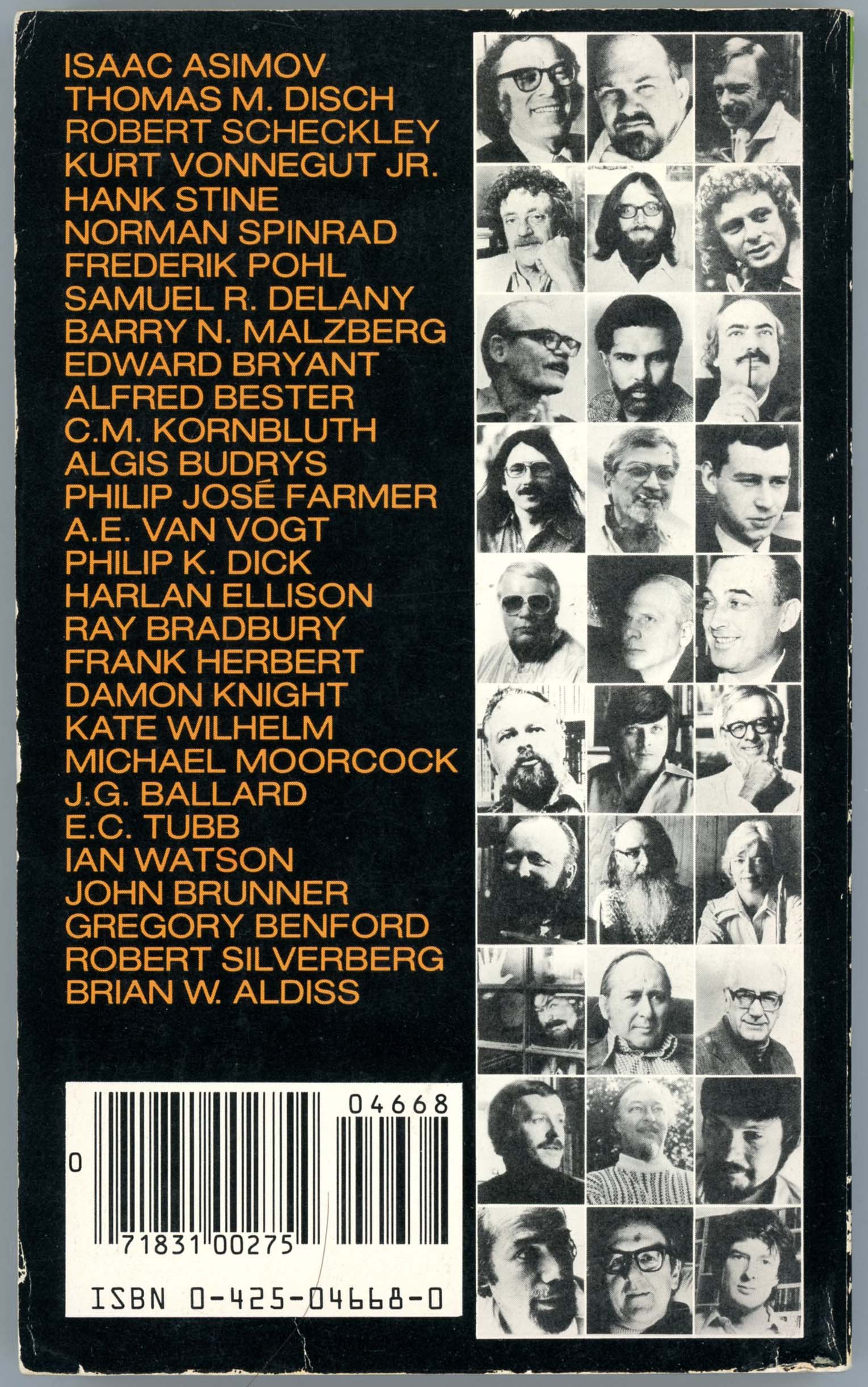

My prior post, regarding Ray Bradbury’s The Fireman (later Fahrenheit 451), presented musings about his novel viewed in the context of the events of the year 2020, and, in terms of the effect of “information technology” in the contemporary world, which seem to have been anticipated in his novel. This serves as an introduction to images of the magazine and book cover art associated with Fahrenheit 451’s first appearance:in Galaxy Magazine (under the title The Fireman), and next, as Ballantine Books’ publication of the novel under that much-more-familiarly-known title. In turn, the post includes excerpts from some of the novel’s passages that are the most powerful, descriptive, and relevant to the world we now live in.

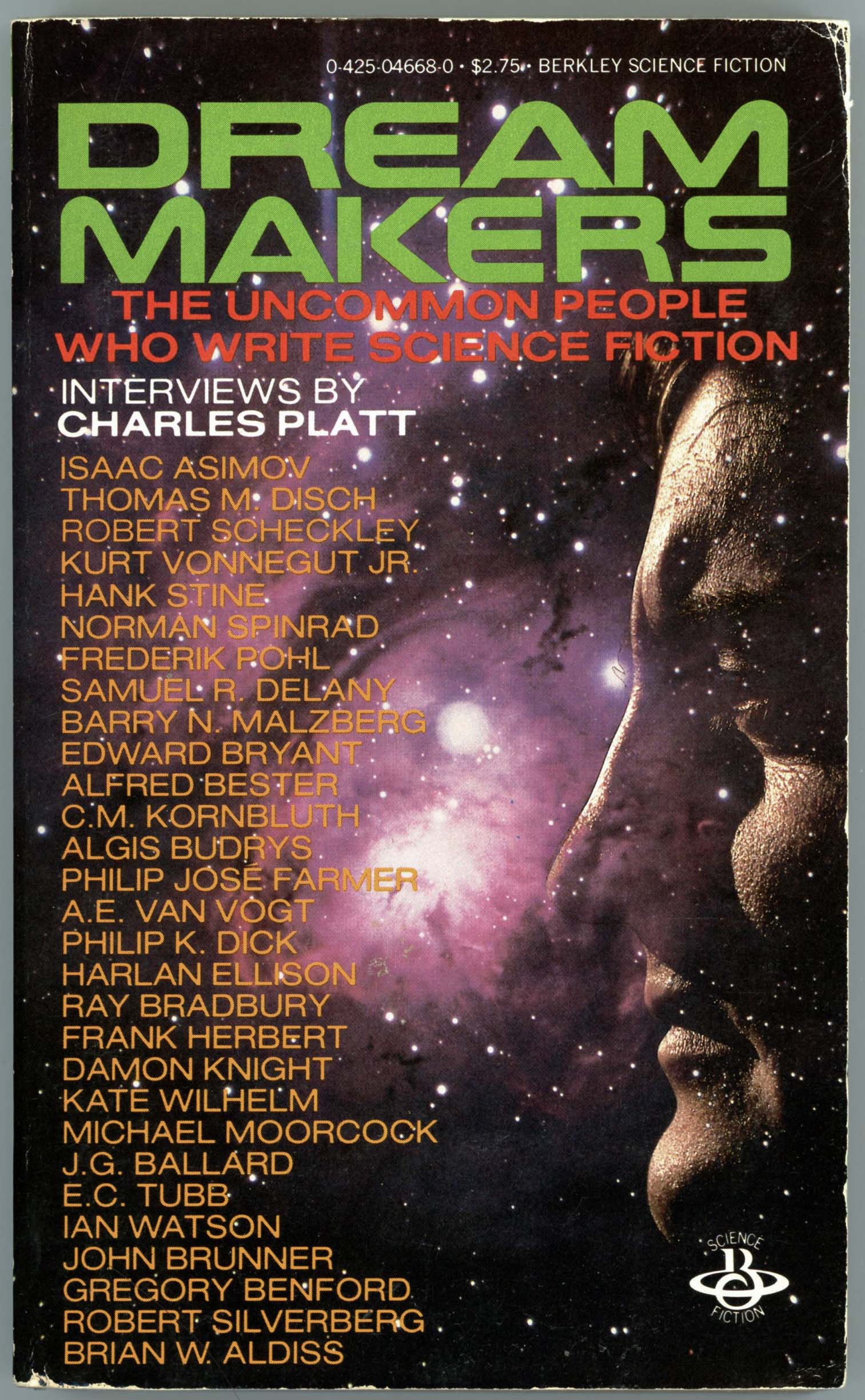

This post is quite different in nature: It’s the text of an interview with Ray Bradbury that appeared in Charles Platt’s Dream Makers – The Uncommon People Who Write Science Fiction, published in November of 1980 by Berkley Books. The author’s conversation with his Ray Bradbury occurred in Los Angeles in May of 1979.

Platt’s book is excellent, for the reader gains an appreciation through exchanges with 29 authors of not only their relationship with the world of writing, but simply about their personal histories (sometimes their families, too) and lives, as “people”. Albeit, the profile of Cyril Kornbluth is by definition and nature not an interview as such, Kornbluth having died in 1958! Thus, Kornbluth’s brief biographical profile is based on Charles Platt’s taped interview with Kornbluth’s widow Mary, which occurred in November of 1973.

(Alas, I so wish that something had been included about Cordwainer Smith or Catherine L. Moore!)

Profiled in the book are:

Brian W. Aldiss

Isaac Asimov

J.G. Ballard

Gregory Benford

Alfred Bester

Ray D. Bradbury

John Brunner

Edward Bryant

Algis Budrys

Samuel R. Delaney

Philip K. Dick

Thomas M. Disch

Harlan Ellison

Philip Jose Farmer

Frank Herbert

C.M. (Cyril M.) Kornbluth

Damon Knight

Barry N. Malzberg

Michael Moorcock

Frederik Pohl

Robert Scheckley

Robert Silverberg

Norman Spinrad

Hank Stine

E.C. Tubb

A.E. (Alfred Elton) van Vogt (…see more at the Kenneth Spencer Research Library, at the University of Kansas…)

Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.

Ian Watson

Kate Wilhelm

So, here’s Charles Platt’s interview with Ray Bradbury. If I emerged from reading Fahrenheit 451 with an appreciation of Bradbury’s literary skill, I emerged from reading Platt’s interview with a solid appreciation of Bradbury as “a person”. A person, most impressive, at that.

________________________________________

Ray Bradbury

Ray Bradbury’s stories speak with a unique voice. They can never be confused with the work of any other writer. And Bradbury himself is just as unmistakable: a charismatic individualist with a forceful, effusive manner and a kind of wide-screen, epic dedication to the powers of Creativity, Life, and Art.

He has no patience with commercial writing which is produced soullessly for the mass market:

“It’s all crap, it’s all crap, and I’m not being virtuous about it; I react in terms of my emotional, needful self, in that if you turn away from what you are, you’ll get sick some day. If you go for the market, some day you’ll wake up and regret it. I know a lot of screenwriters; they’re always doing things for other people, for money, because it’s a job. Instead of saying, ‘Hey, I really shouldn’t be doing this,’ they take it, because it’s immediate, and because it’s a credit. But no one remembers that credit. If you went anywhere in Los Angeles among established writers and said, ‘Who wrote the screenplay for Gone With the Wind?” they couldn’t tell you. Or the screenplay for North by Northwest. Or the screenplay for Psycho – even I couldn’t tell you that, and I’ve seen the film eight times. These people are at the beck and call of the market; they grow old, and lonely, and envious, and they are not loved, because no one remembers. But in novels and short stories, essays and poetry, you’ve got a chance of not having, necessarily, such a huge audience, but having a constant group of lovers, people who show up in your life on occasion and look at you with such a pure light in their faces and their eyes that there’s no denying that love, it’s there, you can’t fake it. When you’re in the street and you see someone you haven’t seen in years – that look! They see you and, that light, it comes out, saying, My God, there you are, Jesus God it’s been five years, let me buy you a drink… And you go into a bar, and – and that beautiful thing, which friendship gives you, that’s what we want, hah? That’s what we want. And all the rest is crap. It is. That’s what we want from life – “ He pounds his fist on the glass top of his large, circular coffee table. “ – We want friends. In a lifetime most people only have one or two decent friends, constant friends. I have five, maybe even six. And a decent marriage, and children, plus the work that you want to do, plus the fans that accumulate around that work – Lord, it’s a complete life, isn’t it – but the screenwriters never have it, and it’s terribly sad. Or the Harold Robbinses of the world – I mean, probably a nice gent. But no one cares, no one cares that he wrote those books, because they’re commercial books, and there’s no moment of truth that speaks to the heart. The grandeur and exhilaration of certain days is missing – those gorgeous days when you walk out and it’s enough just to be alive, the sunlight goes right in your nostrils and out your ears, hah? That’s the stuff. All the rest – the figuring out of the designs, for how to do a bestseller – what a bore that is. Lord, I’d kill myself, I really would, I couldn’t live that way. And I’m not being moralistic. I’m speaking from the secret wellsprings of the nervous system. I can’t do those things, not because it’s morally wrong and unvirtuous, but because the gut system can’t take it, finally, being untrue to the gift of life. If you turn away from natural gifts that God has given you, or the universe has given you, however you want to describe it in your own terms, you’re going to grow old too soon. You’re going to get sour, get cynical, because you yourself are a sublime cynic for having done what you’ve done. You’re going to die before you die. That’s no way to live.”

He speaks in a rich, powerful voice-indeed, a hot-gospel voice – as he delivers this inspirational sermon. He may be adopting a slightly more incisive style than usual, for the purposes of this interview, and he may be using a little overstatement to emphasize his outlook; but there can be no doubt of his sincerity. Those passages of ecstatic prose in his fiction, paying homage to the vibrant images of childhood, the glorious fury of flaming rockets, the exquisite mystery of Mars, the all-around wonder-fullness of the universe in general – he truly seems to experience life in these terms, uninhibitedly, unreservedly.

Intellectual control and cold, hard reason have a place, too; but they must give way to emotion, during the creative process:

“It takes a day to write a short story. At the end of the day, you say, that seems to work, what parts don’t? Well, there’s a scene here that’s not real, now, what’s missing? Okay, the intellect can help you here. Then, the next day, you go back to it, and you explode again, based on what you learned the night before from your intellect. But it’s got to be a total explosion, over in a few hours, in order to be honest.

“Intellectualizing is a great danger. It can get in the way of doing anything. Our intellect is there to protect us from destroying ourselves – from falling off cliffs, or from bad relationships – love affairs where we need the brains not to be involved. That’s what the intellect is for. But it should not be the center of things. If you try to make your intellect the center of your life you’re going to spoil all the fun, hah? You’re going to get out of bed with people before you ever get into bed with them. So if that happens – the whole world would die, we’d never have any children!” He laughs. “You’d never start any relationships, you’d be afraid of all friendships, and become paranoid. The intellect can make you paranoid about everything, including creativity, if you’re not careful. So why not delay thinking till the act is over? It doesn’t hurt anything.”

I feel that Bradbury’s outlook, and his stories, are unashamedly romantic. But when I use this label, he doesn’t seem at all comfortable with it.

“I’m not quite sure I know what it means. If certain things make you laugh or cry, how can you help that? You’re only describing a process. I went down to Cape Canaveral for the first time three years ago. I walked into it, and yes, I thought, this is my home town! Here is where I came from, and it’s all been built in the last twenty years behind my back. I walk into the Vehicle Assembly Building, which is 400 feet high, and I go up in the elevator and look down – and the tears burst from my eyes. They absolutely burst from my eyes! I’m just full of the same awe that I have when I visit Chartres or go into the Notre Dame or St. Peter’s. The size of this cathedral where the rockets take off to go to the moon is so amazing, I don’t know how to describe it. On the way out, in tears, I turn to my driver and I say, ‘How the hell do I write that down? It was like walking around in Shakespeare’s head.’ And as soon as I said it I knew that was the metaphor. That night on the train I got out my typewriter and I wrote a seven-page poem, which is in my last book of poetry, about my experience at Canaveral walking around inside Shakespeare’s head.

“Now, if that’s romantic, I was born with romantic genes. I cry more, I suppose – I’m easy to tears, I’m easy to laughter, I try to go with that and not suppress it. So if that’s romantic, well, then, I guess I’m a romantic, but I really don’t know what that term means. I’ve heard it applied to people like Byron, and in many ways he was terribly foolish, especially to give his life away, the way he did, at the end. I hate that, when I see someone needlessly lost to the world. We should have had him for another five years – or how about twenty? I felt he was foolishly romantic, but I don’t know his life that completely. I’m a mixture; I don’t think George Bernard Shaw was all that much of a romanticist, and yet I’m a huge fan of Shaw’s. He’s influenced me deeply, along with people like Shakespeare, or Melville. I’m mad for Shaw; I carry him with me everywhere. I reread his prefaces all the time.”

Quite apart from what I still feel is a romantic outlook, Bradbury is distinctive as a writer who shows a recurring sense of nostalgia in his work. Many stories look back to bygone times when everything was simpler, and technology had not yet disrupted the basics of small-town life. I ask him if he knows the source of this affection for simplicity.

“I grew up in Waukegan, Illinois, which had a population of around 32,000, and in a town like that you walk everywhere when you’re a child. We didn’t have a car till I was twelve years old. So I didn’t drive in automobiles much until I came west when I was fourteen, to live in Los Angeles. We didn’t have a telephone in our family until I was about fifteen, in high school. A lot of things, we didn’t have; we were a very poor family. So you start with basics, and you respect them. You respect walking, you respect a small town, you respect the library, where you went for your education – which I started doing when I was nine or ten. I’ve always been a great swimmer and a great walker, and a bicyclist. I’ve discovered every time I’m depressed or worried by anything, swimming or walking or bicycling will generally cure it. You get the blood clean and the mind clean, and then you’re ready to go back to work again.”

He goes on to talk about his early ambitions: “My interests were diverse. I always wanted to be a cartoonist, and I wanted to have my own comic strip. And I wanted to make films, and be on the stage, and be an architect – I was madly in love with the architecture of the future that I saw in photographs of various world’s fairs which preceded my birth. And then, reading Edgar Rice Burroughs when I was ten or eleven, I wanted to write Martian stories. So when I began to write, when I was twelve, that was the first thing I did. I wrote a sequel to an Edgar Rice Burroughs book.

“When I was seventeen years old, in Los Angeles, I used to go to science-fantasy meetings, downtown. We’d go to Clifton’s Cafeteria; Forrest Ackerman and his friends would organize the group there every Thursday night, and you could go there and meet Henry Kuttner, and C.L. Moore, and Jack Williamson, and Edmond Hamilton, and Leigh Brackett – my God, how beautiful, I was seventeen years old, I wanted heroes, and they treated me beautifully. They accepted me. I still know practically everyone in the field, at least from the old days. I love them all. Robert Heinlein was my teacher, when I was nineteen… but you can’t stay with that sort of thing, a family has to grow. Just as you let your children out into the world – I have four daughters – you don’t say, ‘Here is the boundary, you can’t go out there.’ So at the age of nineteen I began to grow. By the time I was twenty I was moving into little theater groups and I was beginning to experiment with other fictional forms. I still kept up my contacts with the science-fiction groups, but I mustn’t stay in just that.

“When I was around twenty-four, I was trying to sell stories to Colliers and Harper’s and The Atlantic, and I wanted to be in The Best American Short Stories. But it wasn’t happening. I had a friend who knew a psychiatrist. I said, ‘Can I borrow your psychiatrist for an afternoon?’ One hour cost twenty dollars! That was my salary for the whole week, to go to this guy for an hour. So I went to him and he said, ‘Mr. Bradbury, what’s your problem?’ And I said, ‘Well, hell, nothing’s happening.’ So he said, ‘What do you want to happen?’ And I said, ‘Well, gee, I want to be the greatest writer that ever lived.’ And he said, “That’s going to take a little time, then, isn’t it?’ He said, ‘Do you ever read the encyclopedia? Go down to the library and read the lives of Balzac and Du Maupassant and Dickens and Tolstoy, and see how long it took them to become what they became.’ So I went and read and discovered that they had to wait, too. And a year later I began to sell to the American Mercury, and Collier’s, and I appeared in The Best American Short Stories when I was twenty-six. I still wasn’t making any money, but I was getting the recognition that I wanted, the love that I wanted from people I looked up to. The intellectual elite in America was beginning to say, “Hey, you’re okay, you’re all right, and you’re going to make it.’ And then my girlfriend Maggie told me the same thing. And then it didn’t matter whether the people around me sneered at me. I was willing to wait.”

In fact, Bradbury must have received wider critical recognition, during the late 1950s and into the 1960s, than any other science-fiction author. His work used very little technical jargon, which made it easy for “outsiders” to digest, and he acquired a reputation as a stylist, if only because so few science-fiction authors at that time showed any awareness of style at all.

Within the science-fiction field, however, Bradbury has never received as much acclaim, measured (for example) by Hugo or Nebula awards. Doe this irk him?

“That’s a very dangerous thing to talk about.” He pauses. Up till this moment, he has talked readily, with absolute confidence. Now, he seems ill-at-ease. “I left the family, you see. And that’s a danger… to them. Because, they haven’t got out of the house. It’s like when your older brother leaves home suddenly – how dare he leave me, hah? My hero, that I depended on to protect me. There’s some of that feeling. I don’t know how to describe it. But once you’re out and you look back and they’ve got their noses pressed against the glass, you want to say, ‘Hey, come on, it’s not that hard, come on out.’ But each of us has a different capacity for foolhardiness at a certain time. It takes a certain amount of – it’s not bravery – it’s experimentation. Because I’m really, basically, a coward. I’m afraid of heights, I don’t fly, I don’t drive. So you see I can’t really claim to be a brave person. But the part of me that’s a writer wanted to experiment out in the bigger world, and I couldn’t help myself, I just had to go out there.

“I knew that I had to write a certain way, and take my chances. I sold newspapers on a street comer, for three or four years, from the time I was nineteen till I was twenty-two or twenty-three years old. I made ten dollars a week at it, which was nothing, and meant that I couldn’t take girls out and give them a halfway decent evening. I could give them a ten-cent malted milk and a cheap movie, and then walk them home. We couldn’t take the bus, there was no money left. But, again, this was no virtuous selection on my part. It was pure instinct. I knew exactly how to keep myself well.

“I began to write for Weird Tales in my early twenties, sold my short stories there, got twenty or thirty dollars apiece for them. You know everything that’s in The Martian Chronicles, except two stories, sold for forty, fifty dollars apiece, originally.

“I met Maggie when I was twenty-five. She worked in a bookstore in downtown Los Angeles, and her views were so much like mine – she was interested in books, in language, in literature – and she wasn’t interested in having a rich boyfriend; which was great, because I wasn’t! We got married two years later and in thirty-two years of marriage we have had only one problem with money. One incident, with a play. The rest of the time we have never discussed it. We knew we didn’t have any money in the bank, so why discuss something you don’t have, hah? We lived in Venice, California, our little apartment, thirty dollars a month, for a couple of years, and our first children came along, which terrified us because we had no money, and then God began to provide. As soon as the first child arrived my income went up from fifty dollars a week to ninety dollars a week. By the time I was thirty-three I was making $110 a week. And then John Huston came along, and gave me Moby Dick [the film for which Bradbury wrote the screenplay] and my income went up precipitously in one year – and then went back down the next year, because I chose not to do any more screenplays for three years after that, it was a conscious choice and an intuitive one, to write more books and establish a reputation. Because, as I said earlier, no one remembers who wrote Moby Dick for the screen.

“Los Angeles has been great for me, because it was a collision of Hollywood – motion pictures – and the birthing of certain technologies. I’ve been madly in love with film since I was three years old. I’m not a pure science-fiction writer, I’m a film maniac at heart, and it infests all of my work. Many of my short stories can be shot right off the page. When I first met Sam Peckinpah, eight or nine years ago, and we started a friendship, and he wanted to do Something Wicked This Way Comes, I said, ‘How are you going to do it?’ And he said, ‘I’m going to rip the pages out of your book and stuff them in the camera.’ He was absolutely correct. Since I’m a bastard son of Erich von Stroheim out of Lon Chaney – a child of the cinema – hah! – it’s only natural that almost all of my work is photogenic.”

Is he happy with the way his stories have been made into movies?

“I was happy with Fahrenheit 451: I think it’s a beautiful film, with a gorgeous ending. A great ending by Truffaut. The Illustrated Man I detested; a horrible film. I now have the rights back, and we’ll do it over again, some time, in the next few years. Moby Dick – I’m immensely moved by it. I’m very happy with it. I see things I could do now, twenty-five years later, that I understand better, about Shakespeare and the Bible – who, after all, instructed Melville at his activities. Without the Bible and Shakespeare, Moby Dick would never have been born. Nevertheless, with all the flaws, and with the problem of Gregory Peck not being quite right as Ahab – I wanted someone like Olivier; it would have been fantastic to see Olivier – all that to one side, I’m still very pleased.”

In the past few years Bradbury has turned increasingly toward writing poetry as opposed to short stories. Not all of this poetry has been well-received. I ask him if he suffers from that most irritating criticism – people telling him that his early work was better.

“Oh, yes, and they’re – they’re wrong, of course. Steinbeck had to put up with that. I remember hearing him say this. And it’s nonsense. I’m doing work in my poems, now, that I could never have done thirty years ago. And I’m very proud. Some of the poems that have popped out of my head in the last two years are incredible. I don’t know where in hell they come from, but – good God, they’re good! I have written at least three poems that are going to be around seventy years, a hundred years from now. Just three poems, you say? But the reputation of most of the great poets are based on only one or two poems. I mean, when you think of Yeats, you think of Sailing to Byzantium, and then I defy you, unless you’re a Yeats fiend, to name six other poems.

“To be able to write one poem in a lifetime, that you feel is so good it’s going to be around for a while… and I’ve done that, damn it, I’ve done it – at least three poems – and a lot of short stories. I did a short story a year ago called Gotcha, that is, damn it, boy, that’s good. It’s terrifying! I read it and I say, oh, yes, that’s good. Another thing, called The Burning Man, which I did two years ago … and then some of my new plays, the new Fahrenheit 451, a totally original new play based on what my characters are giving me, at the typewriter. I’m not in control of them. They’re living their lives all over again, twenty-nine years later, and they’re saying good stuff. So long as I can keep the channels open between my subconscious and my outer self, it’s going to stay good.

“I don’t know how I do anything that I do, in poetry. Again, it’s instinctive, from years and years and years of reading Shakespeare, and Pope – I’m a great admirer of Pope – and Dylan Thomas, I don’t know what in hell he’s saying, a lot of times, but God it sounds good, Jesus, it rings, doesn’t it, hah? It’s as clear as crystal. And then you look closely and you say, it’s crystal – but I don’t know how it’s cut. But you don’t care. Again, it’s unconscious, for me. People come up and say. Oh, you did an Alexandrian couplet here. And I say, Oh, did I? I was so dumb, I thought an Alexandrian couplet had to do with Alexander Pope!

“But from reading poetry every day of your life, you pick up rhythms, you pick up beats, you pick up inner rhymes. And then, some day in your forty-fifth year, your subconscious brings you a surprise. You finally do something decent. But it took me thirty, thirty-five years of writing, before I wrote one poem that I liked.”

There is no denying this man’s energy and his enthusiasm. It’s so directly expressed, and so guileless, it makes him a likeable and charming man regardless of whether you identify with his outlook or share his opinions. He projects a mixture of innocence and sincerity; he looks at you directly as he speaks, as if trying to win you over and catalyze you into sharing his enthusiasm. He is a tanned, handsome figure, with white hair and. often, white or light-colored clothing; the first time I ever saw him, at a science-fiction convention, he seemed almost regal, standing in his white suit, surrounded by a mass of scruffy adolescent fans in dowdy T-shirts and jeans. Yet he seemed to empathize with them; despite his healthy ego he is not condescending toward his younger admirers, perhaps because he still feels (and looks) so young at heart himself. In a way he is forever living the fantasies he writes, about the nostalgic moments of childhood. He has a child’s sense of wonder and naive, idealistic spirit, as he goes around marveling at the world. He has not become jaded or disillusioned either about science fiction or about its most central subject matter, travel into space.

“We have had this remarkable thing occurring during the last ten years, when the children of the world began to educate the teachers, and said, ‘Here is science fiction, read it’; and they read it and they said, ‘Hey, it’s not bad,’ and began to teach it. Only in the last seven or eight years has science fiction gotten respectable.

“Orwell’s 1984 came out thirty years ago this summer. Not a mention of space travel in it, as an alternative to Big Brother, a way to get away from him. That proves how myopic the intellectuals of the 1930s and 1940s were about the future. They didn’t want to see something as exciting and as soul-opening and as revelatory as space travel. Because we can escape, we can escape, and escape is very important, very tonic, for the human spirit. We escaped Europe 400 years ago and it was all to the good, and then from what we learned, by escaping, we could come back and say, ‘Hey, we’re going to refresh you, we got our revolution, now maybe we can all revolt together against certain things.’ My point is that intellectual snobbishness permeated everything, including all the novels, except in science fiction. It’s only in the last ten years we can look back and say, ‘Oh, my God, we really were beat up all the time by these people, and it’s a miracle we survived.’“

But, I suggest, a lot of the mythic quality of space travel has been lost, now that NASA has made it an everyday reality.

“I believe that any great activity finally bores a lot of people,” he replies, “and it’s up to us ‘romantics’ – hmm?” (he makes it clear, he still dislikes the term) “to continue the endeavor. Because my enthusiasm remains constant. From the time I saw my first space covers on Science and Invention, or Wonder Stories, when I was eight or nine years old – that stuff is still in me. Carl Sagan, a friend of mine, he’s a ‘romantic,’ he loves Edgar Rice Burroughs – I know, he’s told me. And Bruce Murray, who’s another friend of mine, who’s become president of Jet Propulsion Laboratories – first time I’ve ever known someone who became president of anything! – and he’s a human being, that’s the first thing, and he happens, second, to be the president of a large company that’s sending our rockets out to Jupiter and Mars. I don’t think it’s been demystified. I think a lot of people were not mystified to begin with, and that’s a shame.”

Is Bradbury happy with the growth of science fiction? Does he like modem commercial exploitation of the genre – as in movies like Star Wars?

“Star Wars – idiotic but beautiful, a gorgeously dumb movie. Like being in love with a really stupid woman.” He gives a shout of laughter, delighted by the metaphor. “But you can’t keep your hands off her, that’s what Star Wars is. And then Close Encounters comes along, and it’s got a brain, so you get to go to bed with a beautiful film. And then something like Alien comes along, and it’s a horror film in outer space, and it has a gorgeous look to it, a gorgeous look. So wherever we can get help we take it, but the dream remains the same: survival in space and moving on out, and caring about the whole history of the human race, with all our stupidities, all the dumb things that we are, the idiotic creatures, fragile, broken creatures. I try to accept that; I say, okay, we are also the ghosts of Shakespeare, Plato, Euripedes and Aristotle, Machiavelli and Da Vinci, and a lot of amazing people who cared enough to try and help us. Those are the things that give me hope in the midst of stupidity. So what we are going to try and do is move on out to the moon, get on out to Mars, move on out to Alpha Centauri, and we’ll do it in the next 500 years, which is a very short period of time; maybe even sooner, in 200 years. And then, survive forever, that is the great thing. Oh, God, I would love to come back every 100 years and watch us.

“So there it is, there’s the essence of optimism – that I believe we’ll make it, and we’ll be proud, and we’ll still be stupid and make all the dumb mistakes, and part of the time we’ll hate ourselves; but then the rest of the time we’ll celebrate.”

(Los Angeles, May 1979)

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Ray Bradbury is probably best known for The Martian Chronicles (1950), his enduring collection of stories which use off-the-shelf science-fiction hardware (rocket ships, the planet Mars colonized by man), but explore these ideas in a spirit of fantasy as opposed to predictive reality. Bradbury’s vision of the ‘lost race’ of Martians was powerful enough to eclipse all others and become a tradition, followed in many subsequent science-fiction novels by other writers.

The Illustrated Man (1951) presents fantasy and horror stories linked by the slightly artificial device of embodying key scenes in tattoos on the body of a man who has supposedly journeyed through the various events. Fahrenheit 451 (1953) is a novel depicting a repressive future where all books must be burned, and firemen start the fires rather than put them out. The October Country (1955) is a collection of fantasy and macabre stories. Something Wicked This Way Comes (1962) is a novel depicting a peaceful, innocent small town, visited by a sinister carnival which brings pure evil.

Bradbury’s recent poetry, much of it dealing with science-fiction themes, appears in a couple of recent collections.