“I speak to you now:

A poet and Jew in the crucifix kingdom.”

~~~~~~~~~~

“And now we descend, we come down from the ladder

We fashioned and raised: the spirit of Europe.

A love, universal, even for Jew-haters.

A kingdom of heaven for all human souls.”

My prior post, “The Flight of the Albatross – Uri Zvi Greenberg and “Albatros””, is an overview of the life and work of the Uri Tzvi Greenberg, one of whose most expressive and impassioned works is the poema “In the Crucifix Kingdom” (Yiddish “In malkhus fun tseylem“; alternate titles “By the Kingdom of the Cross” and “In the Kingdom of the Cross”). I first learned about Greenberg via Professor Michael Weingrad’s English-language translation of this work, which appeared (still appears!) at Mosaic Magazine under the title “An Unknown Yiddish Masterpiece That Anticipated the Holocaust – Written in 1923, “In the Crucifix Kingdom” depicts Europe as a Jewish wasteland. Why has no one read it?“.

To say that Professor Weingrad’s translation, let alone my “personal” discovery of other works by Uri Greenberg, was for me quietly amazing … astounding … startling (kudos to the age of science-fiction pulps, for those in the know!) would, perhaps, understate the power of Greenberg’s work. Suffice to say that in 2018 my curiosity led me to review the 1978 Jerusalem reprint of all three issues of Albatros, in order to examine the actual literary venue (well, a reproduction of that venue!) in which this poem first appeared. You can view the “results” of that review here, for this post comprises images of issue three’s cover, and, the text of “In the Crucifix Kingdom” as it was published in the periodical. (Ahem … the reprint.) These images were taken with a 35mm digital SLR (I’m fond of antiques, whether in terms of mechanisms or manuscripts), and, edited for the best possible brightness and contrast. While they don’t have the visual “texture” associated with images of paper (not uncommonly found in digital images of vintage mid-twentieth century pulp fiction magazines which can be viewed at the Pulp Magazine Archive), the clarity is more than sufficient to appreciate and study the world of the Albatros.

As I alluded to in my prior post, Greenberg’s poems (specifically, those from the 1920s) expressed the imperative to reclaim and reconnect Jesus – as a man; as a simple fellow Jew – to the Jewish people, as a fully mortal (and only mortal) human being entirely unencumbered by a millennia-and-longer carapace of accumulated religious and cultural mythology. Such works comprise:

“A World Downward” (Velt barg arop) – 1922

“Mephistopheles” (Mefisto) – 1922

“Before Him” (Lefanav) – 1924

“The Reply” (Ha-ma’aneh) – 1924

“Cut off from all of his brothers, from his blood” (Mehutakh mi-kol ehav, mi-damo) – 1929

“God and His Gentiles” (Elohim ve-goyav)

“The Grave in the Forest” (from “Streets of the River”)

“Proclamation: Leave! (Kruz: tse!)” (from poetry cycle “Earthly Jerusalem”)

“Shortening the Way (Kfitsat ha-derekh)” (final poem in “Earthly Jerusalem”)

“Somewhere in The Fields” (Ergets af felder poem cycle)

The following five lines express this theme succinctly. Though the title of the specific poem is unknown, they’re found on page 68 in Other and Brother – Jesus in the 20th Century Jewish Literary Landscape, edited by Neta Stahl (Oxford, 2013), and are originally from Greenberg, Kol Ketavav (Complete Works), edited Dan Miron (Jerusalem: Mosad Bialik, 1991).

“I accuse His children among the nations of defaming my brothers’ image,

with their beard and earlocks, who look like my brother who was born in Bethlehem;

who spoke my Hebrew tongue and prayed to my God on Mount Moriah;

whom Pilate handed over to the cross and who called out to my God

from the cross in Hebrew, and who died and was buried in my and his Jerusalem.”

This theme reaches its ultimate expression and power – visually as much as textually – in the second issue of Albatros, in the 1922 poem “”Uri Zvi in Front of the Cross INRI (Jesus the Nazarene King of the Jews)”, alternately titled “Uri Zvi Greenberg faren Tslav INRI”, “Uri Zvi Farn Tzelem INRI”, and “Uri Zvi farn tseylem”. You can view this poem in my post about the second issue of Albatros.

I know of two other poets whose works express analogous sentiments. They are the Canadian Irving Layton, one of whose compilations of poetry – For My Brother Jesus – includes eight such-themed poems, and Jacob Glatstein (…see this essay by Dara Horn…) a collection of whose poems, The Selected Poems of Jacob Glatstein (edited by Ruth Whitman) includes two (“Good Night, World”, and “Mozart”). Though their works (at least, as evidenced in these books) do not have the geographic setting, linguistic complexity, and particularly the visual imagery inherent to those of Greenberg, their poems are reminiscent of his in expressing the two millennia of anguish endured by the Jewish people in the sometimes allegorical, sometimes actual ,”worlds” of Edom and Ishmael.

And so, we now embark on our journey through a crucifix kingdom.

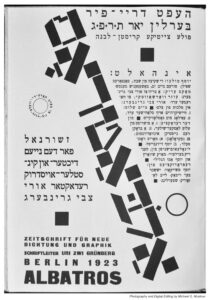

Here’s the first (cover) page of issue three of Albatros. I think the stylized / angled title is a linocut by Henrik Berlevi, Marc Schwartz (most likely), or Yossef Abu HaGlili.

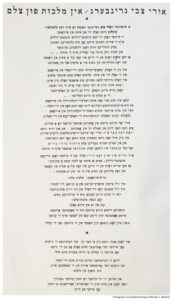

Now, we come to each of the nine pages comprising “In the Crucifix Kingdom”, the poema appearing on pages 15 through 24. I’ve preceded each image with a few stanzas from Professor Weingrad’s translation, these directly corresponding to the “opening” or uppermost stanzas visible at the top of the image. As you can see, all the text is arranged in center-aligned columnar format. The remainder of the translation (not displayed here) can, of course, be found at Mosaic.

Being that the pages are consistent in format, little to no commentary need be added beyond this point.

Begin with page 15…

Page 15

Uri Zvi Greenberg – In malkhus fun tseylem

A forest dense and black has grown upon the plains,

And vales of fear and pain deepen in Europe!

The tree-tops writhe in pain, in wild darkness, wild darkness,

And corpses from the branches hang, their wounds still dripping

blood.

(These heavenly dead all have silver faces,

The moons anoint their brains with golden oil – )

And every cry of pain sounds like a stone in water,

While the prayers of the dead cascade like tears into the deep.

Page 16

I will not plant the trees that bear you fruit,

Only my grieftrees are all set stripped and naked

Near you at the cross’s crown.

From dawn to dusk the bells swing back and forth

Upon your towers.

They drive me mad and tear into my aching flesh

Like mouths of beasts.

Page 17

On a wounded body a shredded tallis – the body

Is good in a Jewish tallis – so good in a tallis:

It keeps the wind from blowing sand into the gaping wounds.

A church-bell rings, the young and old grow feverish –

Cool your fever, Jews! I stand watch over the cemetery

With its open graves.

I bear the Jewish mark, a red gash upon my brow.

Page 18

It’s good for you like this, my frozen father.

Your swollen face in the redness of the setting sun.

You are like a sun.

Yet on the Christian street outside by the well

My mother stands and screams into the water down below:

Give me back my head, you wicked folk, it drowns!

What’s the matter, wicked ones? Is my head so dear to you?

Page 19

Ah, what a curse to live out each day the way we live now:

Any minute a fire will break out under our feet,

From under the houses –

What can we do, this terrorized nation of Jews

With wives and children lamenting: woe for our lives!

And a bloody hue spreads across roof and windowpane.

Page 20

The fifteen million walk silently past you,

Bearing their punishment, eyes like black holes.

For ages they’ve carried a word in their blood

Yet they speak not a word to you now—

I speak to you now:

A poet and Jew in the crucifix kingdom.

With blood from their lungs, so many spit out

The griefword, the curse, and they don’t see the sun

Only moons floating white in the watery blue.

So many, so many, they go on and on

Over dry land and sea, and the wooden post too

That has one of ours bound to it

Crying out: my God, my God! into the void—

Punished, punished, the Jews remain silent

And do not say to you what I have said!

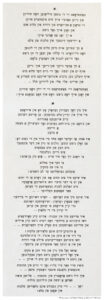

Page 21

Now is the time of the eclipse for you in Europe

It gives me some pleasure that your sun is eclipsed.

For thus does blood still flow in the veins,

The odor of sunset arises from clothes—

O your night will turn red at the crown of the cross!

Your skies that lie over the crosses, I hate them

For they are like brass and they weigh on our grief,

A burden of copper:

No rain for us here.

A curse has been placed upon fields stripped bare—

That you should endure what we have endured!

This page has a small variation on a theme of verticality: The text “From the dawn runs a golden wheel” is arranged in a circle.

Page 22

Birds are flying—such is exile, this marvelous exile:

The great world with its bright and open heart:

At home throughout the world birds fly:

From the dawn runs a golden wheel

The waters of Babylon speak to our feet:

(Evening interrupts. In the air hangs a fog full of tears)

Come to us. You are an orphan. Without a home. That is your pain.

You are weary of travel. The roads go further still.

The shoreline is so vast—lie down and float with the currents

Until we reach the home of every depth and restlessness:

The great and distant sea.

Page 23

Of all black prophecies this is the blackest,

And yet I can feel it in all my bones.

So painful this prophecy, I suffer it always,

Each day in this Christian land of pain.

And now we descend, we come down from the ladder

We fashioned and raised: the spirit of Europe.

A love, universal, even for Jew-haters.

A kingdom of heaven for all human souls.

Page 24

Which red planet should I tell to hover in the sky

When the sun is eclipsed by the void of generations.

When I walk on roads and see my mothers sitting,

How they cradle in their laps their little murdered children

My slaughtered lambs,

My birds,

On the roads of Europe.

East-West-North-South—such fear beneath the crosses!

What then should I do with my good tear-laden arms?

Should I sit also by the roadside under black crosses?

And lull my lambs to sleep,

My birds,

Upon my knees?

Or should I stand and dig a cemetery here in Europe

For my dead lambs,

For my dead birds?

And thus, we come to the end of the “Cruficix Kingdom”. (Double entendre, eh?) Three more flights of the Albatros will follow.

Referentially Speaking…

Uri Zvi Greenberg, at…

… YIVO

Michael Weingrad, at…

Portland State University – Harold Schnitzer Family Program in Judaic Studies

investigations and fantasies on Jews and Fantasy Literature

A Few Academic Reference Works about Uri Zvi Greenberg

Galili, Zeev, Uri Zvi Greenberg – The Poet who Predicted the Holocaust (אורי צבי גרינברג – המשורר שחזה את השואה), at Logic in Madness (Zeev Galili’s online column (היגיון בשיגעון -הטור המקוון של זאב גלילי))

Neuberger, Karin – Between Judaism and the West – The Making of a Modern Jewish Poet in Uri Zvi Greenberg’s “Memoirs (from the Book of Wanderings)”, Polin – Studies in Polish Jewry, Volume Twenty-Four – Jews and Their Neighbours in Eastern Europe since 1750, The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, Portland, Or., 2012, pp. 151-169.

Stahl, Neta, “Uri Zvi Before the Cross”: The Figure of Jesus in the Poetry of Uri Zvi Greenberg”, Religion and Literature, V 40, N 3, Autumn, 2008, pp. 49-80

Weingrad, Michael, An Unknown Yiddish Masterpiece That Anticipated the Holocaust – Written in 1923, “In the Crucifix Kingdom” depicts Europe as a Jewish wasteland. Why has no one read it?, Mosaic.com, April 15, 2015

Otherwise?

Layton, Irving, For My Brother Jesus, McClelland and Stewart Limited, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 1976

Sherman, Kenneth, Irving Layton and His Brother Jesus, Literature & Theology, V 24, N 2, June, 2010, pp. 150-160

Whitman, Ruth, The Selected Poems of Jacob Glatstein, October House Inc., New York, N.Y., 1972