Thus far the only work by Alan Isler that I’ve read, I found the four stories collected within The Bacon Fancier (the title of the book having been derived from the “second” of the four) to be beautifully written, illustrating Mr. Isler’s skill in illustrating commonalities in the historical experience of the Jews transcending time, geography, and the human personality.

Mr. Isler does this through the creation of vividly depicted protagonists whose lives are crafted in the same degree of fullness regardless of the tales’ setting, or, the predicaments or perplexities that fate or personal decision (but are not fate and personal decision sometimes one and the same?) has forced them to contend with.

Similarly, the plot of each of the four tales is constructed with a sensibility that bespeaks of serious historical research, undergirded by an understanding of the complexities and contradictions of human nature. Ultimately, the undercurrent of moral clarity that emerges in his stories could, I think, only have arisen from an author whose own life history or even nominal understanding of life, as a Jew, had included parallel experiences.

And if not parallel experiences, parallel perceptions.

While each of the four stories is excellent as a “stand alone” tale, my favorites are “The Crossing” (as relevant today in 2020, as it was when published in 1997, as imagined by Mr. Isler in the world of the late 1800s), and, “The Bacon Fancier”.

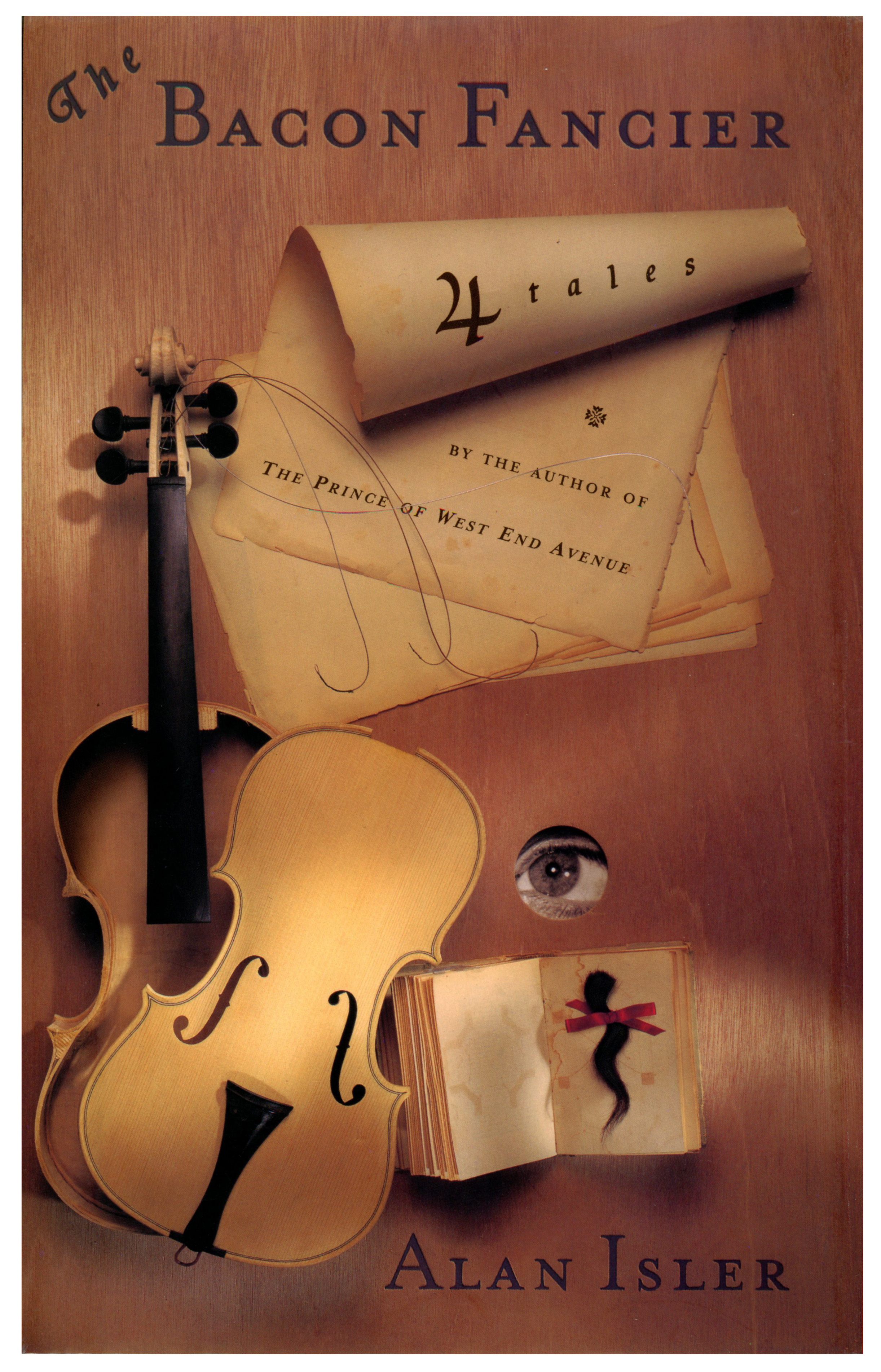

So. Accompanying the image of Mark Tauss’ cover illustration are quotes from those two tales, as well as Michiko Kakutani’s book review of 4 Tales from the New York Times in July of 1997.

____________________

… the hold that time past exerts over time present …

____________________

The New World, so bright and glistening in the pure and frigid air,

so inviting at the birth of the new year,

offered no solace,

no alleviation.

(The Crossing)

Portait of Alan Isler, by Jerry Bauer

Portait of Alan Isler, by Jerry Bauer

________________________________________

I have not lived my life as a Jew, not really, not here in Porlock.

There is a mezuzah on my door, of course,

but I do not observe the holidays,

not even the Days of Awe; all these pass me by.

Candles are alight on my table of a Friday night,

and of a Saturday I do no work.

Still, I eat what I eat, although before Queenie never pork, never shellfish,

never deliberately a mixing of milk and meat;

and since Queenie, well, as I gave said, I found it prudent not to inquire.

Of course, as the year rolls round, I say kaddish for my parents;

that, at least, I have always done.

And I have welcomed the infrequent visits of the occasional Bristol and,

even less frequently, London Jew.

My co-religionists pressed their fingers to my stomach and conveyed them to their lips.

In my home they took only ale or cider or porter, bread, and salted herring.

They talked of the small Jewish communities in this sceptered isle,

in London, in Leeds, in Bristol,

of the importance of marriage, Jew and Jewess,

and of the few others, like me in isolation, the very few, scattered in the south and west,

but married, so far as they knew, every one.

What could have possessed me, they wondered,

a young man, who, apart from a slight physical disability,

enough perhaps to have denied me a priesthood in the ancient Temple –

here, they smiled ironically –

to separate himself from his fellows, to deny himself a helpmeet,

the very heart and hearth of his home?

(Queenie, who cheerfully plied them with that sustenance they would,

at least, hungry, accept,

who soon learned that her puddings and her most accomplished dainties were forbidden,

not to say hateful, to them, they ignored as a nonpresence.)

Why, in short, had I chosen to live alone in Porlock?

Why indeed?

(“The Bacon Fancier”, pp. 52-53)

________________________________________

But Gladstone had had enough.

It was not that he lacked the stomach

to sit through yet another of Miss Courtneidge’s “programs” –

although that much was certainly true,

particularly since she herself had spoken of this evening’s list as “jumbo”.

Nor was it that he longed to return to his stateroom,

where, a little before midnight,

he was to be joined by the lubricious Victoria Gammidge –

although that much too was certainly true.

It was that Gladstone had always felt something alien among his gentile countrymen,

even those of that class among whom he had spent most of his life,

those among whom he moved with seeming ease and freedom.

There was forever something behind their hooded eyes, he felt,

some unspoken thing, that locked him out.

Yet through that he had learned to navigate.

So long as the discreet signposts of social intercourse remained fixed in place,

he negotiated quite successful the world in which fortune had placed him.

But when they began to disappear, as now,

when tongues began to loosen from too much wine,

when eyes began to blear or grew fever bright,

when politesse began to sink into good-fellowship,

then Gladstone began to sense his own vulnerability.

He did not fear a physical attack, of course.

No, what he feared was that the unspoken thing would be given utterance,

that acceptance,

conditional upon a conspiracy of silence,

would be publicly revealed as sham.

Making his excuses to his table companions, he rose and left.

(“The Crossing”, pp. 134-135)

________________________________________

Navigating in a World of Gentiles

By MICHIKO KAKUTANI

THE BACON FANCIER

Four Tales

By Alan Isler

214 pages. Viking. $21.95.

The New York Times

July 22, 1997

Alan Isler’s new book, “The Bacon Fancier,” reads uncannily like a distillation of his work to date. His previously demonstrated weaknesses (most notably a tendency to italicize the significance of his stories) are on display in these pages, as are his previously demonstrated strengths: a gift for authoritative storytelling and an ability to combine comedy and tragedy in a unique, idiomatic voice. What’s more, the volume’s four loosely linked stories recapitulate the central themes of his earlier fiction, the award-winning “Prince of West End Avenue” (1994) and “Kraven Images” (1996): namely, the hold that time past exerts over time present, the role that religion plays in shaping an individual’s identity, and the relationship between art and real life.

Spanning several centuries and two continents, the stories in “The Bacon Fancier” all deal loosely with what it means to be a Jew in a gentile world. The first tale, “The Monster,” is a kind of improvisation on “The Merchant of Venice,” featuring a narrator who bears more than a passing resemblance to Shylock. This narrator gives us his version of the notorious “pound of flesh” trial (he claims that Antonio tricked him into the agreement, as “a merry jest”), then goes on to recount another story that illustrates the anti-Semitism routinely directed against Jews in 16th-century Venice. This second tale concerns a huge but harmless idiot named Mostrino who is beloved by the ghetto children. To get rid of an annoying English tourist who’s intent on trying to win converts to Christianity, the narrator tells him that Mostrino is “the Defender of the Ghetto,” a golem with the power to destroy unbelievers. It is a lie that will have tragic consequences when it collides with the city’s prejudice against the Jews.

In Mr. Isler’s other stories, the effects of anti-Semitism are both less violent and more personal. In the title story, the narrator – a one-eyed violin maker who left the overtly anti-Semitic world of 18th-century Venice for the more covertly anti-Semitic world of London – contemplates leaving his gentile mistress,

Queenie, for a Jewish girl he can marry. Though he loves Queenie and Queenie loves him, he knows that they can never enjoy a respectable life together. Indeed Queenie will always be known as the “Jooey Zoor,” the “Jew’s Whore.”

Things are little better, Mr. Isler suggests, in the New World. In “The Crossing,” a Jewish orphan named David, who has been adopted by the wealthy Gladstone family, boards a ship bound for America. Though David’s adoptive parents own a financial interest in the ship, though David is traveling first class, he soon becomes aware of the prejudice directed against him. He is mocked at dinner (“Gladstone?” says another dinner guest, “I’d’ve thought Disraeli”), put down by the father of a young woman he would like to court, and openly scorned by the ship’s captain, when he questions the actions of a drunken American bully.

Gladstone “had always felt somewhat alien among his gentile countrymen,” writes Mr. Isler, adding: “There was forever something behind their hooded eyes, he felt, some unspoken thing, that locked him out. Yet through that he had learned to navigate. So long as the discreet signposts of social intercourse remained fixed in place, he negotiated quite successfully the world in which fortune had placed him. But when they began to disappear, as now, when tongues began to loosen from too much wine, when eyes began to blear or grow fever bright, when politesse began to sink into good-fellowship, then Gladstone began to sense his own vulnerability. He did not fear a physical attack, of course. No, what he feared was that the unspoken thing would be given utterance, that acceptance, conditional upon a conspiracy of silence, would be publicly revealed as sham.”

By the time we reach the last story, set in contemporary New York, anti-Semitism is less a conscious prejudice than a casual byproduct of callousness and greed. In this case, the hero – an extra in a small Greenwich Village opera company – is offered the chance to star in a musical about the Dreyfus affair. While he finds the show shallow and offensive, he – like many others – will profit from its success.

While Mr. Isler’s efforts to link these four stories feel highly perfunctory and his efforts to lend them resonance through a series of literary allusions can feel strained, his sheer abilities as a storyteller force the reader to shrug such misgivings aside. There is an assurance to his writing that enables him to fold digressions and speculative asides effortlessly into his tales, coupled with a wry affection for his characters that makes their stories poignant and funny and sad. Mr. Isler did not begin writing until late middle age – his first novel, “The Prince of West End Avenue” was published when he was 60 – but these stories make it clear that he’s a natural.