The war was over – I had survived.

I was home, safe in the land of my birth.

Only my innocence had died, and with it my youth.

Fair or not fair, right or wrong, whether I wanted it or not, whether anyone liked it or not

– I had a life to live.

I was twenty-one.

In a number of previous posts, I presented cover art for books authored by veterans of the Second World War who’d served as combat fliers in the United States Army Air Force, and, Royal Air Force. Regardless of the different personalities of these authors; regardless of the differences in military duties of these men and the theaters of war in which they served; regardless of their styles of literary expression, the central and consistent tone emerging from these books is one of contemplation – deep and profound contemplation – and seriousness.

For all of these men, the constant threat of injury or death, comradeship and the inevitable loss of comrades (which these men directly witnessed), the numbing routine – psychologically and physically – of combat flying, and, the inherent unpredictability of the future, were transformative at a level which the written word can sometimes express quite clearly, and at other times, only indirectly.

(But, you can even learn something from “indirection”!)

In this context, John Sigler Boeman’s memoir Morotai: A Memoir of War, is superb, in terms of military aviation history, and in a larger sense, as a work of literature. Boeman served as a B-24 Liberator pilot in the 371st Bomb Squadron of the 13th Air Force’s 307th (“Long Rangers“) and later as a career Air Force officer, flying C-54s and B-52s, serving in both the Korean and Vietnam Wars. He passed away at the relative young (these days) age of 74 in 1998, seventeen years after the first publication of Morotai.

Morotai is vividly descriptive, whether in “capturing” the personalities of Boeman’s crew members (the men are presented honestly and not as caricatures, as occurred – in a different vein – in the ridiculously overrated television series M*A*S*H, the animating ideology of which was always apparent…), living conditions at Morotai (an island in eastern Indonesia’s Halmahera Group), or the psychological and physical challenges and complexities of combat flying. An unusual aspect of the book is that an underlying theme of uncertainty – about the technical skill and ability of the author and his crew; about the nature of the military effort their Squadron and Group were tasked with; about the “future” immediate and the “future” distant – hovers throughout its pages.

The literary tone of the book probably emerged from what seems to have been Mr. Boeman’s inherently contemplative, introspective disposition. But, it also arises from the book’s final two chapters, in which the author recounts – with utter and remarkable candor – the take-off crash of his bomber on May 29, 1945, an accident which claimed the lives of four of his crew members, and eventuated in the disbandment of his crew as a unified group of aviators. By retelling his story chronologically and placing the jarring account of the take-off crash in the book’s final pages, one gets the impression that structuring the memoir in this manner may have been a kind of literary catharsis for Mr. Boeman: A catharsis entirely understandable, and deserving of respect.

The book ends with Boeman’s departure from the 371st Bomb Squadron and return to his home in Illinois. There he would be, during Japan’s surrender several weeks later.

So… the dust jacket of Morotai (Doubleday first edition) appears below. Strangely, the illustration depicts a B-24D Liberator in desert-pink camouflage, rather than the later-model natural metal finish Liberators actually piloted by Boeman: Ooops… Somebody in Doubleday’s art department should have paid more attention!

______________________________

______________________________

Here’s a review of Morotai by Captain Carl H. Fritsche that appeared in Aerospace Historian in Fall of 1981.

“John Boeman, a farm youth from Illinois, enlisted in the Army Air Corps and he was inducted into the military service in March 1943. Morotai is a book of his experiences in the WW II cadet program and of his 20 combat missions as a B-24 pilot in the Southwest Pacific Area. The book is an in-depth analysis of the author’s thoughts, hopes, frustrations, successes, and failures during the global conflict.

John Boeman is an excellent writer. There were no 1,000-plane raids staged from the small island of Morotai, so the author takes you with him on each of his small squadron’s flights to bomb a single bridge, ship, or gun emplacement. As Boeman gains confidence in his ability as a combat B-24 commander, his career is shattered by his own “pilot error” takeoff crash in which several of his crew members are killed. The psychological impact of the plane crash was devastating and Boeman was sent home. WW II ends as Boeman returns to his home town and Boeman completes the book with an excellent analysis of his success and failure in the conflict.

Morotai is a good book about one man’s life and his one failure as a plane commander. The publisher’s note in the back of the book is important as John Boeman did not allow his own failure as a pilot to defeat him. He returned to the military service and served many years as a B-52 plane commander as well as many other very important assignments before retiring from the Air Force in 1972.

______________________________

Morotai, first published by Doubleday in 1981, was republished in an illustrated edition by Sunflower University Press in 1989. This second edition included several photographs from John Boeman’s personal collection, some of which are shown below:

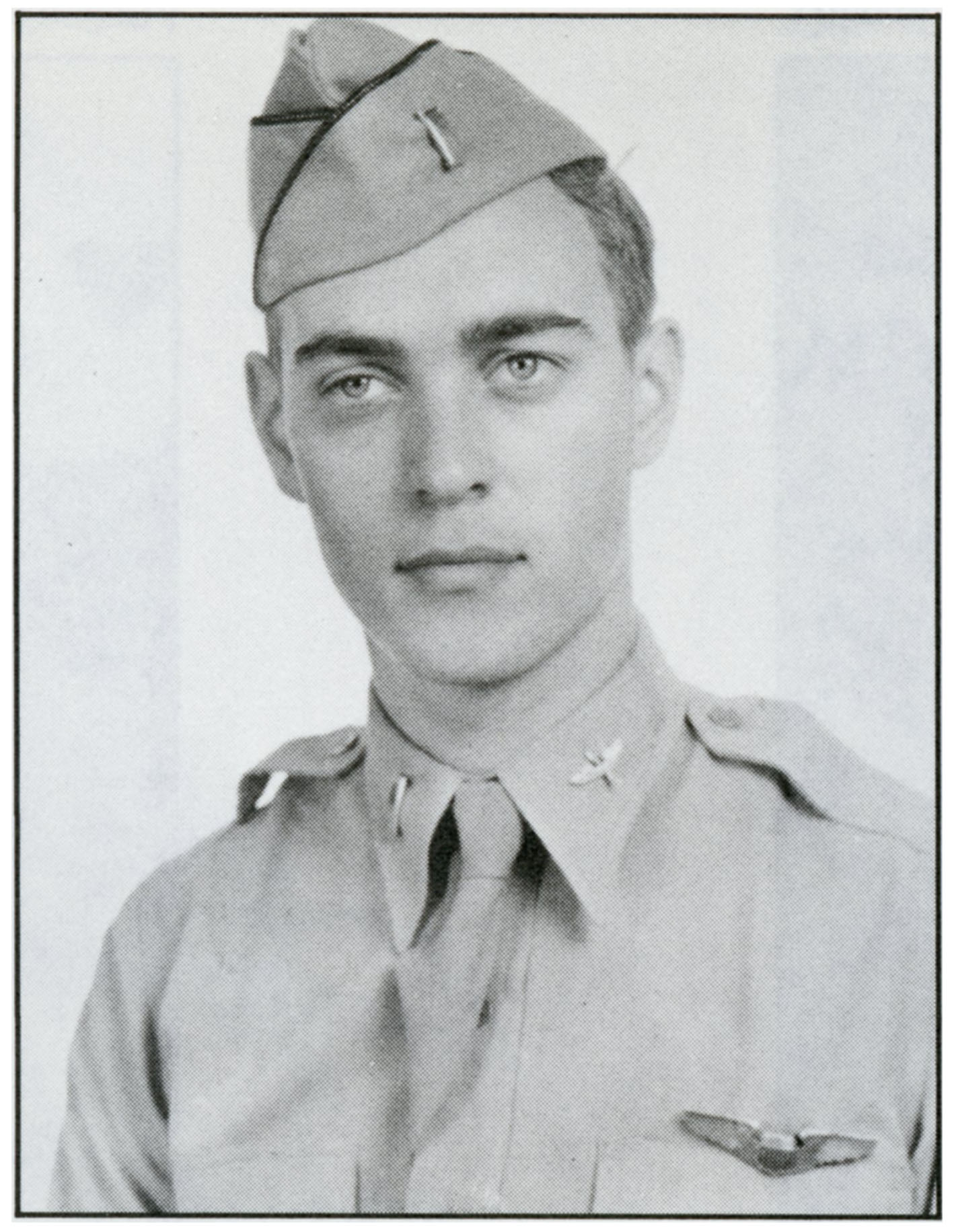

Lieutenant John Sigler Boeman

______________________________

______________________________

Lieutenant Boeman’s crew, posed on the wing of B-24J 44-40946, an aircraft of the 372nd Bomb Squadron.

Standing (back row), left to right

1 Lt. John S. Boeman, Il. – Pilot

2 Lt. Joseph C. Miller, N.J. – Co-Pilot

F/O Alton Charles Dressler, Hershey, Pa. – Navigator, T-132887 (Killed in crash)

WW II Honoree Page by Mrs. Jean Dressler Heatwole (sister)

F/O Joseph Pasternak, St. Louis, Mo. – Bombardier

Seated (front row), left to right

S/Sgt. Arnold Jerome Shore, Philadelphia, Pa. – Waist Gunner, 33777766 (Killed in crash)

S/Sgt. William J. Harrington, Minneapolis, Mn. – Radio Operator

S/Sgt. William P. Brown, Poulsbo, Wa. – Ball Turret Gunner

S/Sgt. Leonard I. Sikorski, Milwaukee, Wi. – Flight Engineer

S/Sgt. David G. Swecker, Clarksburg, W.V. – Tail Gunner

S/Sgt. Ernest James Smieja, Minneapolis, Mn. – Nose Gunner, 37569058 (Killed in crash)

Not in photo

S/Sgt. Eppa Hunton Johnson, Alexandria, Va. – Photographer, 33540167 (Died of injuries June 1, 1945)

______________________________

This is F/O Alton Dressler’s tombstone, via FindAGrave contributor Glen Koons

And, the tombstone of S/Sgt. Arnold J. Shore.

And, the tombstone of S/Sgt. Arnold J. Shore.

______________________________

______________________________

Another view of B-24J 44-40946

______________________________

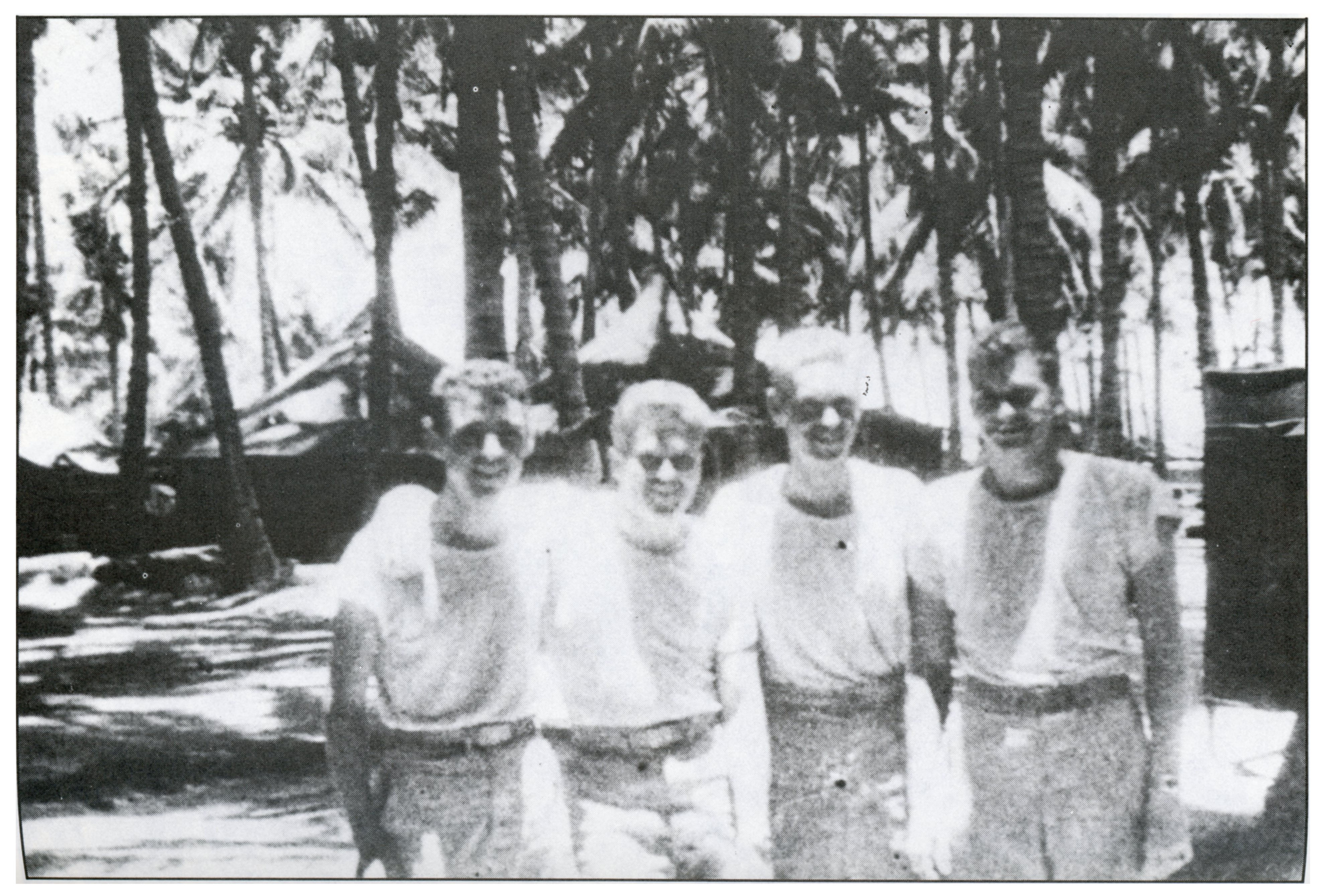

John Boeman and his fellow Officers

Left to right

Left to right

F/O Joseph Pasternak (Bombardier)

2 Lt. Joseph C. Miller (Co-Pilot)

1 Lt. John S. Boeman

F/O Alton C. Dressler (Navigator)

______________________________

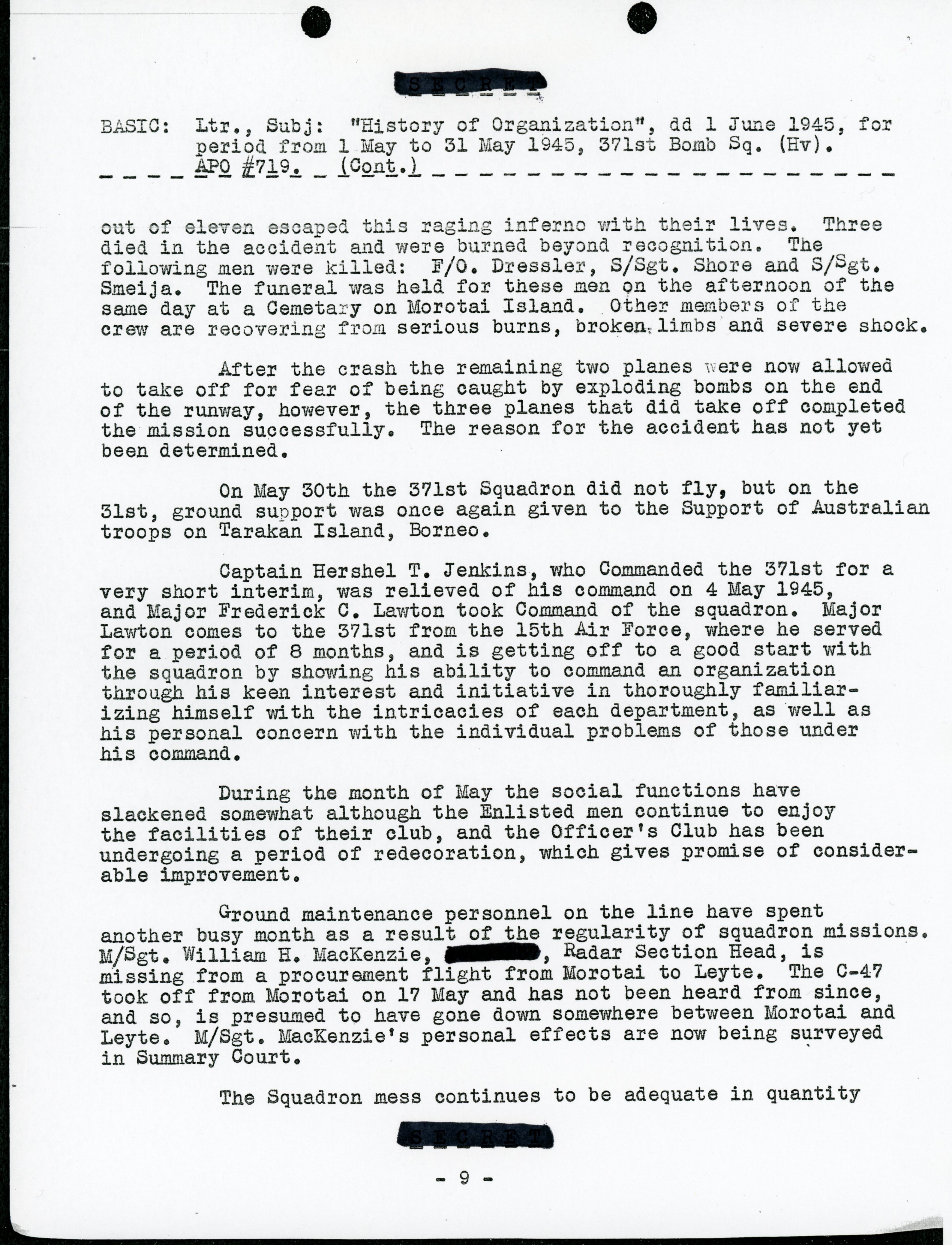

Some years ago, I contacted the Air Force Historical Records Center at Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama, to learn more about the tragic accident that figures so prominently in John Boeman’s book. It turns out that no Accident Report exists for this incident, that document having been lost since the Second World War, or (more likely!) never having been filed in the first place. However, the events of May 29, 1945, are well covered in the Squadron History for that month, the pages of which are shown below.

On May 29th, tragedy struck at the 371st when six planes were lined up for an early dawn take-off. Three planes were already airborne when Lt. Boeman in A/C #548 crashed at the end of the runway. Within a matter of minutes, his plane burned and two of the 6 1000# GP bombs exploded and four were blown clear and did not explode. By some unexplainable miracle of fate eight crew members out of eleven escaped this raging inferno with their lives. Three died in the accident and were burned beyond recognition. The following men were killed: F/O Dressler, S/Sgt. Shore and S/Sgt. Smeija. The funeral was held for these men on the afternoon of the same day at a Cemetery on Morotai Island. Other members of the crew are recovering from serious burns, broken limbs and severe shock.

On May 29th, tragedy struck at the 371st when six planes were lined up for an early dawn take-off. Three planes were already airborne when Lt. Boeman in A/C #548 crashed at the end of the runway. Within a matter of minutes, his plane burned and two of the 6 1000# GP bombs exploded and four were blown clear and did not explode. By some unexplainable miracle of fate eight crew members out of eleven escaped this raging inferno with their lives. Three died in the accident and were burned beyond recognition. The following men were killed: F/O Dressler, S/Sgt. Shore and S/Sgt. Smeija. The funeral was held for these men on the afternoon of the same day at a Cemetery on Morotai Island. Other members of the crew are recovering from serious burns, broken limbs and severe shock.

______________________________

B-24L Liberator 44-41548, “Polly”, which would eventually be so central to John Boeman’s journeys, both life and literary. (Images from B-24 Best Web)

______________________________

At Morotai, the funeral of Flight Officer Alton C. Dressler, from 307th Bomb Group, at Fold3.com

______________________________

______________________________

Some passages from Morotai…

After dinner, Dad drove, with Mom in the seat beside him as always.

I sat in the back seat and watched city lights fade away to country darkness.

Near midnight, turning into our farm lane,

the car’s headlights flashed across the big white house where I was brought into the world.

Dad stopped under the big maple tree near the front porch.

I got out into the still, dark, warm night air among the summer cornfields.

The urge was strong to block the past three years from my mind,

to forget it all,

as I went into the house with my parents.

“I gave Lowell your bedroom when he came to stay with us,” my mother said.

“You can sleep in the big bedroom, where your brother used to sleep.

Is that all right?”

“Oh. Okay, sure, that’s fine,” I said, and carried my B-4 bag up the stairs.

Bogey had missed by one day.

On my first full day at home,

President Truman announced Japanese acceptance of the Potsdam surrender terms.

My mother asked me to attend special prayers with them at church.

I agreed.

I remembered that big white church on the north side of town.

Long ago, the lady who taught Sunday school,

when she was not pumping and playing the organ,

had told me how God knew everything.

“He knows all about each of us,”

she had said as we little boys and girls listened from straight-backed chairs.

“He knows how many hairs we have on our head.

He knows every time we are good and every time we are bad.

He takes care of good little boys and girls …”

Now I listened to the pastor in that same church.

His words, it seemed to me,

thanked God for taking care of those who were good –

by ending the war.

I sensed, perhaps unfairly, smug satisfaction that victory had confirmed goodness.

The pastors’ pious recitation of God’s hand,

in vindication, seemed to ignore those who, I knew,

deserved more than I to be home with loved ones.

Did God end the war? I asked myself.

If He did, did He start it?

Can we blame our enemies for the beginning and thank God for the ending?

No.

War, from the beginning to the end,

must be an affair of men,

in which God plays no favorites.

How dare we be so arrogant as to believe that God would help us,

just because we prayed for it,

to kill and defeat those whom we select as enemies?

Had there not been those among our enemies who asked God’s help, too, in their way?

Would an omnipotent God sell his favors for a few prayers?

Were my crewmates, who fell victim to my shortcomings,

less deserving of God’s help than I?

As we left the church, I had not the words to describe my feelings,

to articulate my thoughts.

To avoid burdening my parents with my reaction to the service, I said nothing.

On our way home, passing the village main street, I saw people gathered.

Home, I borrowed the car and returned to town.

On the one-block main street of the village I had known as my hometown all my life,

they had built a bonfire.

While some in our town thanked God for ending the war,

others chose to vent emotions in a ritual that closing the village taverns could not inhibit.

Parked around the corner,

I got out and approached a scene that struck me as one from an old movie,

in which barbaric tribesmen were whipping themselves to frenzy.

They had sacrificed their young men to appease the demon and ward off dark evils.

Now, celebrating their success, they were giving their thanks to the Great God War for sparing them.

Flames shot up from the fire.

Amid shouts and yells, a pair of teenaged boys,

obviously drunk,

approached in an automobile.

One waved a whiskey bottle out the window while the other drove through the edge of the fire.

The crowd cheered, what, their bravery?

What are they cheering? I asked myself.

What are they celebrating?

“Hello, Johnny.” A voice I remembered.

One of the few girls who had called me Johnny, instead of John, in school.

Once I had thought her the most beautiful creature on earth,

but had never told her so.

I had never kissed her, never asked.

There had always been another boy, regarded by our peers as her “steady.”

Conforming to the code of our time and place,

maybe from shyness,

I had tried to keep from exposing my true feelings about her.

“I heard you were coming home,” she said.

“Come on and join the snake dance.”

She held out her hand.

The cool pressure of her fingers in mine excited old emotions.

We joined the crowd forming in a line, holding hands,

to dance and run through the street and around the fire.

I knew she had married a “steady” since I left.

He was overseas.

Was the invitation a friendly overture for old time’s sake,

or was it the approach of a lonely married woman yielding to temptation in the excitement?

By the end of the dance, I was afraid to know the answer.

Whichever, it could lead to complications I did not want to face.

I disentangled myself and moved to the sidewalk beyond the crowd.

What are they celebrating?

I asked myself the question again.

Among them I recognized some I had known well when the decisive battles were still to be fought. They had not seen those as their battles.

They had not sworn to obey any orders.

They had taken no oath.

They had pledged not their lives, their fortunes, nor their Sacred Honor.

Yet they accepted the victory as theirs,

as if by Divine Right, attained, by them,

simply by waiting for it.

Now they celebrated peace, their peace.

The street scene filled me with consternation equal to that I had felt in the church.

I had known these people.

I could put names to all their faces.

But now they were strangers to me, living in a world apart from mine.

I wanted their silly celebrations no more than their pious prayers.

I wanted to run away.

I wanted to run away, but to where?

Turn my back because they prayed, or celebrated?

Should I condemn them for not seeing a world I saw?

I had been raised among them, with them, as one of them.

By what right could I now say I was not one of them?

If not one of them, who could I be?

My commitment to win the war had been total,

but if not on their behalf, then on whose?

I could not answer.

The war was over – I had survived.

I was home, safe in the land of my birth.

Only my innocence had died, and with it my youth.

Fair or not fair, right or wrong, whether I wanted it or not, whether anyone liked it or not

– I had a life to live.

I was twenty-one.

I would find new dreams, new commitments.

I locked the consternating questions within myself, without answers,

and stepped off the sidewalk into the crowd.

I joined the survivors.

______________________________

References

Boeman, John S., Morotai – A Memoir of War, Doubleday & Company, Inc., Garden City, N.Y., 1981 (1st Edition)

Boeman, John S., Morotai – A Memoir of War, Sunflower University Press, Manhattan, Ks., 1989 (2nd Edition; Illustrated)

Fritsche, Carl H. (Book Review), Morotai – A Memoir of War by John Boeman, Aerospace Historian, V 28, N 3, Fall, 1981, p. 212

307th Bomb Group Aircraft Inventory and Air Crew Losses, at 307th BG

B-24J 44-40946 (no nickname), at B-24 Best Web

B-24L 44-41548 (Polly) – 5 images, at B-24 Best Web