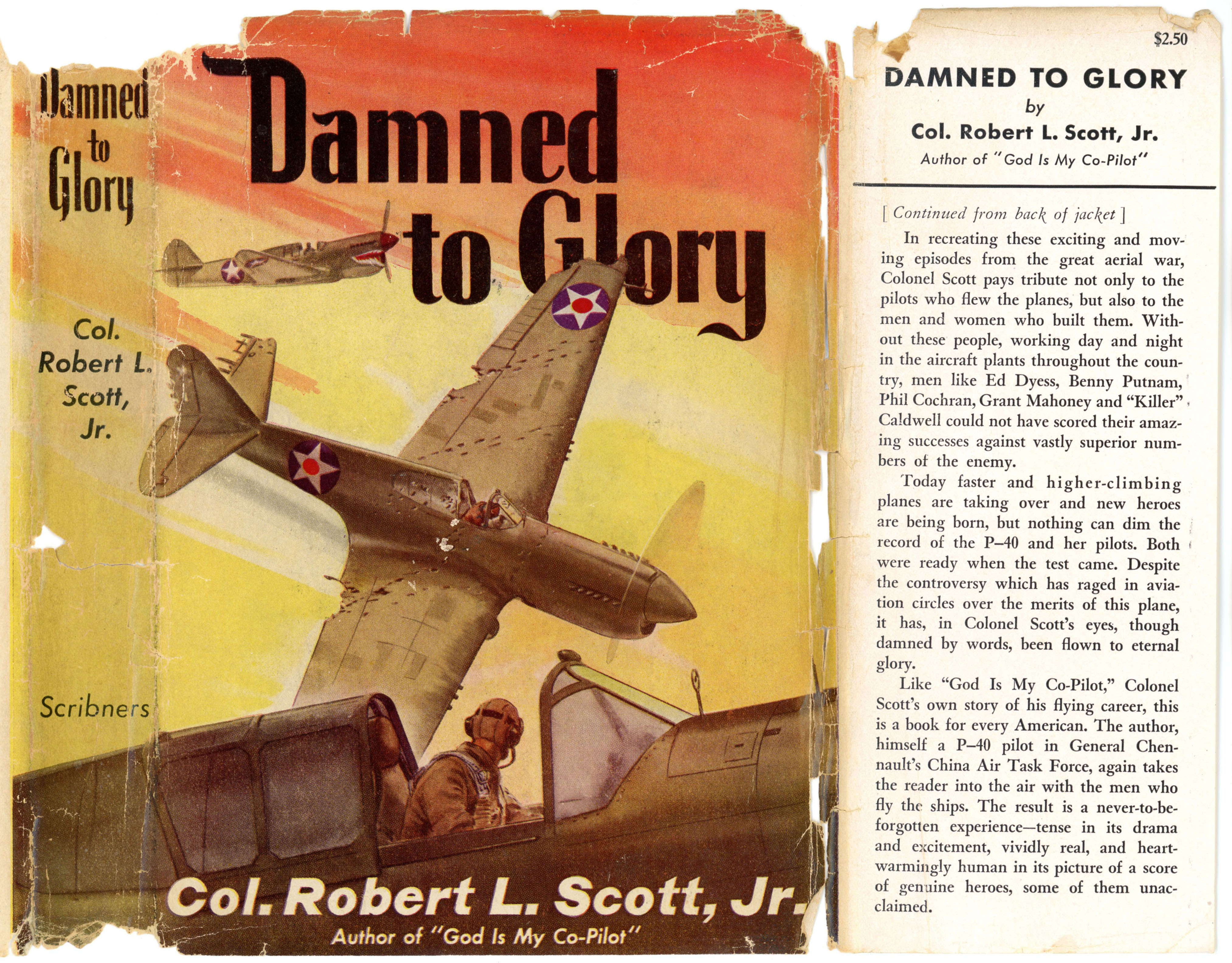

This is the third post presenting an excerpt from Colonel Robert L. Scott’s 1944 Damned to Glory, which covers the service and use of the Curtiss P-40 fighter plane in the air forces of the United States and Allied nations during the Second World War.

While my two prior posts about Damned to Glory pertained to the use of the P-40 in the United States Army Air Force (51st Fighter Group, in Assam Dragon) and South African Air Force (during the “Cape Bon Massacre” of April 22, 1943, in Desert Rats), “this” post moves to Europe: It presents Colonel Scott’s chapter about the use of the P-40 in the Soviet Air Force (“Военно-воздушные силы”, or Voyenno-Vozdushnye Sily (a.k.a. VVS)) in a chapter entitled “Wool of the Russian Ram”. Scott relates accounts of the experiences of Soviet pilots (Aleksey Stepanovich Khlobistov, Petr Andreevich Pilootov, and Stepan Grigorevich Ridniy), and also mentions Pyotr Afanasyevich Pokryshev, all of whom piloted the Curtis P-40 in battle against the Luftwaffe.

The chapter’s very title is a double entendre, for it’s illustrated by Lloyd Howe’s depiction of a Soviet pilot committing a “taran” – a controlled aerial ramming – against a German Me-109 fighter. The illustration is based on an account Aleksey Khlobistov’s destruction of an Me-109 on May 14, 1942, while defending the city of Murmansk.

“Wool of the Russian Ram” follows below…

I have flown beside the Russian

I have flown beside the Russian

At the siege of Stalingrad,

It was there I met the Prussian,

Heard the Hun cry “Kamerad!”

Impotence and rage might rankle

When my guns would freeze and stall,

Till I learned to ram the Heinkel,

Slashed his tail—and watched him fall.

WOOL OF THE RUSSIAN RAM

THERE’S a story that’s just about as wild as the winds of the frozen steppes of Siberia, a story vouched for by Johnny Alison and Herbert Zempke [Hubert Zemke]. Incidentally, these two and the same Phil Cochran of the Red Scarf Guerrillas once lived together as bachelors at Langley Field, around 1936. How in heaven’s name this came about no one will ever know; the only good that could have come from this consolidation of talent was that one telephone-number could reach the three most eligible bachelors on the post. Even then they branched out as the individuals and leaders they really were, and the house must have been as distinctly Alison, Zempke and Cochranish as were their respective techniques in flying.

From the 8th Pursuit Squadron at Langley, which was the first real P-40 squadron in the Army Air Forces, Alison went with Harry Hopkins to Russia. Zempke joined him at Archangel in September, 1941, while poor Phil sweated the war out as he trained fighter pilots in the States.

P-40’s arrived at Archangel aboard transports, and Alison and Zempke helped put them together under a hard-fighting Russian officer, Col. Boris Schmirnoff. Boris had fought the Japs in Mongolia, the Germans and Italians in the Spanish Civil War, and had operated against the Finns. In his black Russian boots, which were always shined like a mirror, he was an inspiration of aggressive nature even to such stalwarts as these two Americans.

Here at Archangel, Alison and Zempke checked out 120 Russian pilots in ten days. They were amazed, back there in 1941, at the ability of the Russian pilots to absorb instruction, and at their keen interest to get to combat and kill the Hun. As a pilot’s joke, though, Johnny said the Red pilots knew only two positions for a throttle – “closed” and “full open.”

These Russian flyers were destined for great things. From the check-out school, the Russian P-40 pilots were sent to Rostov-on-Don, where they lived in railroad cars when they were not in the air against the Germans. One of these pilots was Senior Lieutenant Stepan Grigorievich Ridny, aged twenty-three. Ridny’s squadron was equipped entirely with P-40’s, and it fought on the Moscow front. There, in the first week, his squadron shot down nineteen Huns and lost three men and three ships.

In that early period of the war Ridny was one of the best-known pilots in Russia; he had been in the Soviet Air Force since becoming seventeen years of age, and he had been decorated with the Order of Lenin and had been created “A Hero of the Soviet Union.” Short and strongly built, as he sat in the cockpit of the Kittyhawk, with his light brown hair blowing over his face, he looked the part of a great Russian pilot. Born near Kharkov, he had met a few Americans and liked them.

From Rostov, Ridny was transferred with his squadron to Moscow, for the defense of that city. There in P-40’s they shot down 29 German planes in two weeks.

On the Leningrad front, Major Peter Adrievich Piliutov took a lone P-40 aloft for a check flight and was attacked by six Heinkels. He shot down two of them and damaged a third. At the start of the new year of 1942, Piliutov’s squadron of Tomahawks supported the Russian ground troops and helped them to recapture three hundred square miles of territory from the invaders. During the five-day drive over the frozen wastes of this northern section near Finland, the Tomahawks functioned perfectly. Four of them shot down eight Messerschmitts and routed others at low altitude under the clouds. On missions of a certain type the P-40 was successfully used there on skis.

But the prize air exploit took place on the Murmansk front, above the jagged ice of the frozen sea, where the P-40 squadrons were used to keep the Nazi dive bombers from attacking munition and food convoys. It was near there that one of the Soviet pilots, Alexei Khobistoff, showed himself a man of stern determination, and proved too that his ship could “take it.”

The first time he “rammed” an enemy ship, Khobistoff declared it was an accident. He had been trailing a Heinkel bomber for about fifty miles as it darted in and out of the low clouds of the north country. When finally he pressed his trigger for the kill, nothing happened – the guns were either frozen or jammed. He drew away and made another attempt, with the same negative result. In the meantime, the German gunners fired at him, and his ship was hit repeatedly.

Undaunted, Khobistoff approached the Heinkel through one of its few blind areas and tried once more to make his guns fire. As he took his eyes from the larger ship to turn the hydraulic charging instruments again, he struck the Nazi plane with the wing and prop of his P-40. There was a noise like the end of the world, sparks flew from the friction of the steel propeller cutting into the Heinkel’s wing – and then the Tomahawk skipped on over, and into the low clouds. By the time Khobistoff had regained control of the fighter, the Heinkel had crashed. The Russian flew home to his base, where the American fighter was patched up and again flown into combat.

Later this same Russian in a P-40 again found himself in a desperate position directly astern of a German bomber. He drew closer and closer to the tail of the enemy ship, and by expert flying passed his prop into the fabric rudder of the Hun. Once again the German crashed, and again Khobistoff returned to his base, where mechanics repaired the plane.

About a week later, as he flew top-cover out over the harbor to protect a convoy arriving from America, his squadron engaged many Messerschmitts. In the hotly contested battle, Khobistoff shot down two Huns, but was in turn wounded, and his Tomahawk was set on fire. I imagine that right about there any other man would have opened the hatch and jumped. But not this Russian. He turned the burning fighter and dove straight down on the tail of an Me-109. As the whirling propeller of the P-40 made contact, the tail of the Hun flew into pieces – Khobistoff had rammed to destruction his third enemy aircraft. Then he jumped clear of the burning Tomahawk. As his ‘chute opened, he saw the Messerschmitt strike the muddy beach of the harbor, and his flaming P-40 streaking like an avenging devil right after it.

Alexei Khobistoff was in the hospital a few weeks, but here’s hoping somebody sent him another P-40 when he was released.

To substantiate these three collisions, two of which were intentional, there are official Soviet records. Moreover, the Russian Air Force has published for its pilots a directive on “Ramming Procedure.” In several instances during the siege of Stalingrad, there were other pilots who rammed German planes and not only escaped with their lives, but in some cases flew their damaged planes back to the home base. One of these was Russia’s outstanding Ace, Major Alexandrevich Pokryshev (Pyotr Afanasyevich Pokryshev), who has fifty-nine German planes to his credit.

______________________________

Comments…

Herbert Zempke is almost certainly – well is certainly! – “Hubert Zemke”. (Veritably: “Oops.”)

Stepan Grigorievich Ridny is Hero of the Soviet Union Stepan Grigorevich Ridniy (Степан Григорьевич Ридный). Born in 1917, he was killed in action on February 17, 1942, while serving in the 126th Fighter Aviation Regiment.

Peter Adrievich Piliutov is Hero of the Soviet Union Petr Andreevich Pilootov (Петр Андреевич Пилютов). Born in 1906, he died in 1960.

Alexei Khobistoff is – as alluded to above – Hero of the Soviet Union Aleksey Stepanovich Khlobistov (Алексей Степанович Хлобыстов). Born in 1918, he was killed in action as a Guards Captain on December 13, 1943, while serving in the 20th Guards Fighter Aviation Regiment (1st Composite Aviation Division, 7th Air Army).

Major Alexandrevich Pokryshev is twice Hero of the Soviet Union Pyotr Afanasyevich Pokryshev (Пётр Афана́сьевич Покры́шев). Born in 1914, he attained 30 or 31 aerial victories, eventually commanding the 159th Fighter Aviation Regiment (275th Fighter Division, 13th Air Army). He died in 1967.

The painting below is a depiction of Major Pokryshev flying his P-40E (“white 50”, bearing stars indicating 15 aerial victories) during an attack against a pair of Heinkel He-111 bombers, during his service in the 154th Fighter Aviation Regiment. The painting, entitled “Curtiss P-40 – One of many Lend-Lease P-40 used by the Soviets in WWII, claims a He 111 over the Eastern front“, is by aviation artist Darryl Legg.

An abundance of information exists about the tactic of aerial ramming as practiced by the Soviet Air Force in the Second World War. Notable sites include Aeroram.Narod.RU, AirAces.Narod.RU, and TopWar.RU. Valeriy Romanenko covers Soviet use of the P-40 in “The P-40 Fighter in Soviet Aviation” (“Истребители Р-40 в советской авиации”) in a very detailed 5-part series, commencing at AirPages.RU/US/P-40.

An abundance of information exists about the tactic of aerial ramming as practiced by the Soviet Air Force in the Second World War. Notable sites include Aeroram.Narod.RU, AirAces.Narod.RU, and TopWar.RU. Valeriy Romanenko covers Soviet use of the P-40 in “The P-40 Fighter in Soviet Aviation” (“Истребители Р-40 в советской авиации”) in a very detailed 5-part series, commencing at AirPages.RU/US/P-40.