The cover art of the 1980 edition of Alfred Price’s The Hardest Day – covering the events of the Battle of Britain on August 18, 1940 – depicts an aerial battle from a vantage point highly unusual for aviation art: Rather than viewing aircraft engaging one another in combat from a far vantage point, Phillip Emms shows an air battle from inside of an aircraft. In this case, the battle is seen from the viewpoint of the bombardier of a Heinkel III bomber. He’s firing a nose-mounted 7.9mm machine gun at attacking Hawker Hurricanes of Number 32 Squadron, with the English coastline in the distance.

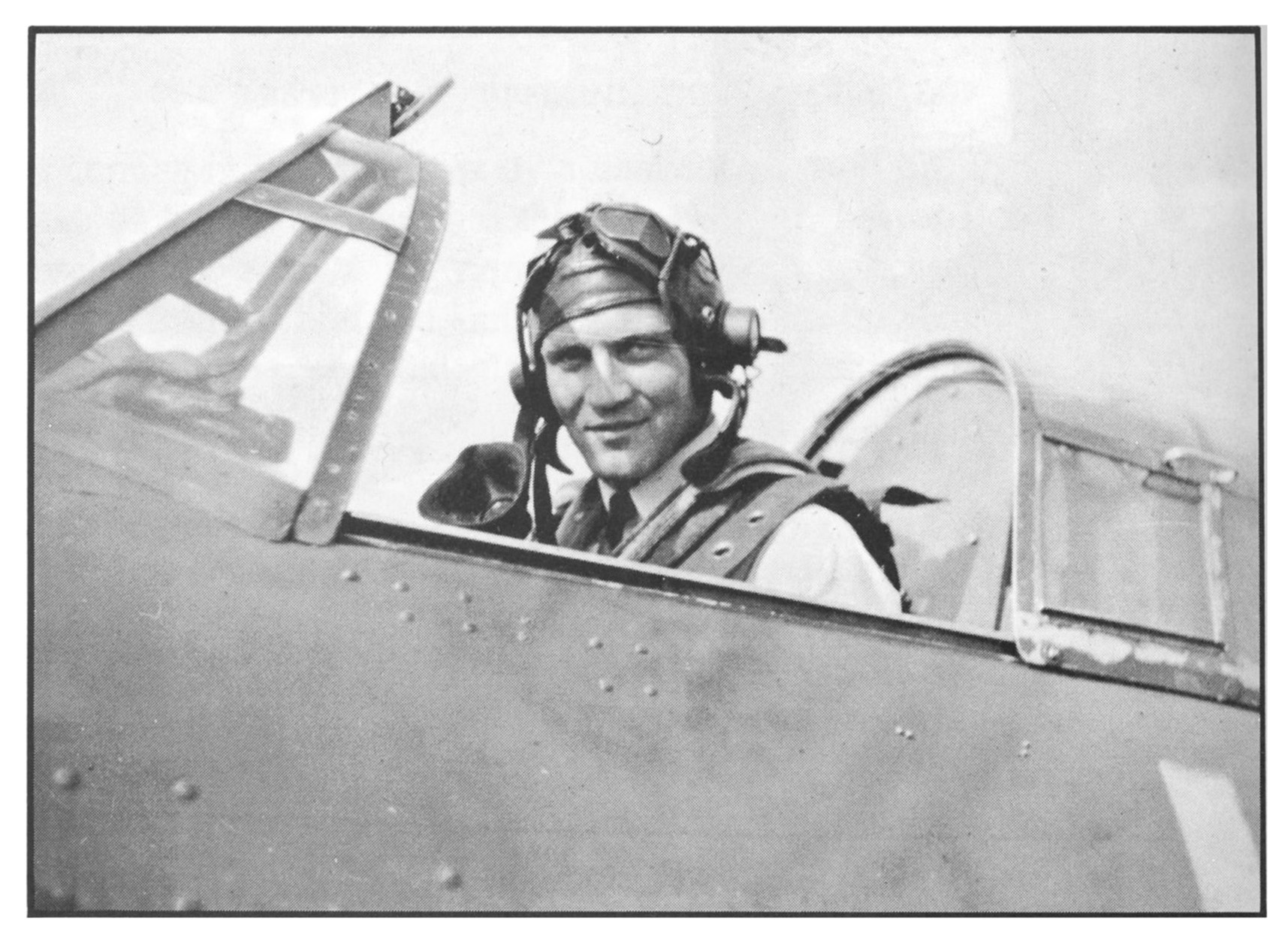

To present the reality of the day’s air battles, below, you can read about the experiences (and the unhappy fate, of one) of four RAF pilots mentioned in Price’s book, accompanied by their photographs. The images of Hugo, Russell, and Wahl are from The Hardest Day, while Solomon’s portrait is from Winston G. Ramsey’s The Battle of Britain: Then and Now.

________________________________________

________________________________________

Author Alfred Price’s biography, from the book jacket: “As an air crew officer in the Royal Air Force for fifteen years, Alfred Price logged more than 4,000 flying hours in 40 different aircraft. He specialized in electronic warfare, aircraft weapons, and air-fighting tactics. He has written more than 14 books on aviation, including Instruments of Darkness, The Bomber in World War II, and Spitfire: A Documentary History, published by Scribners.”

________________________________________

F/O Petrus Hendrik “Dutch” Hugo (Survived)

F/O Petrus Hendrik “Dutch” Hugo (Survived)

Hurricane I R4221

When Pilot Officer ‘Dutch’ Hugo of No 615 Squadron first glimpsed the Messerschmitt 109, it was already too late to do much about it. With ‘A’ Flight he had been orbiting at 25,000 feet, nearly five miles, above Kenley waiting for the enemy to come to him. The Germans did, with breathtaking suddenness, from out of the sun. Seemingly appearing from nowhere the Messerschmitt curved in behind Sergeant Walley on the starboard side of the formation, there was a flash of tracer and his Hurricane went down in flames. Hugo swung his aircraft round to engage the attacker but another Messerschmitt hit him first: ‘There was a blinding flash and a deafening explosion in the left side of the cockpit somewhere behind the instrument panel, my left leg received a numbing, sickening, blow and a sheet of high octane petrol shot back into the cockpit from the main tank. My stricken Hurricane flicked over into a spin and must have been hit half a dozen times while doing so, as the sledgehammer cracks of cannon and machine-gun strikes went on for what seemed ages.’

Without conscious effort Hugo turned off the fuel and opened his throttle, to empty the carburettor and so decrease the risk of fire. The cockpit was awash with petrol and his clothes were saturated with it: the slightest spark would have turned him into a human torch. Finally the engine coughed and spluttered to a stop, the propeller slowed until it was just flicking over in the slipstream, he switched off the ignition and the immediate danger of fire was over. Hugo pushed the stick forwards and eased on rudder to pull out of the spin. He was just straightening out when there was a colossal bang behind him and the now-familiar sound of cannon strikes. ‘I had the biggest fright of my life – I knew I was completely incapable of movement as a particularly vicious-looking Me 109 with a yellow nose snarled about twenty feet past my starboard wing, the venomous crackle of his Daimler Benz engine clearly audible. Round he came for another attack, and although I did everything I could think of, gliding without power has its limitations and the next moment earth and sky seemed to explode into crimson flame as I received a most almighty blow on the side of the head.’

Hugo came to, feeling sick and shaken, to find his aircraft spinning down again. Through a red haze he saw that he was now at 10,000 feet, so he had time to take stock of the situation. His head was aching savagely and the right side of his face felt numb. When he touched it, he found a jagged gash from the comer of his right jaw to his chin. His microphone and oxygen mask had been torn off his helmet and were now draped over his right forearm; the microphone had a bullet hole through it. The cockpit seemed to be filled with a fine red spray; it took Hugo some time to realise that the cause was blood running down his chest being whipped up by the wind whistling through the holes in the sides of his cabin. He slid back the canopy and gasped his lungs full of clean air.

The next thing Hugo knew was that the Messerschmitt was curving round for yet another attack. Enough was enough, he decided to bale out. Hugo rolled the Hurricane on to its back and pulled out the harness locking pin but, instead of falling clear, to his consternation he fell only about twelve inches – sufficient to project his head, arms and shoulders into the blast of the slipstream, which promptly slammed him back against the rear of the cockpit. Before the astonished pilot could decide what to do next the Hurricane solved the problem for him by pulling through a half loop. With a thump Hugo fell back into the cockpit, puzzled but at least able to reach the controls again.

Then he discovered why he had developed such a firm attachment to his aircraft: during the rush to strap in for the scramble take-off, sitting on his parachute in the seat, he had inadvertently taken one of his leg straps round the lever which raised and lowered his seat. Now his own fate was tightly bound up with that of his Hurricane. The next minutes saw Hugo, as he later described, ‘as busy as a one armed one-man bandsman with a flea in his pants’, trying to avoid the attentions of his persistent foe, finding and doing up his seat straps in readiness for the inevitable crash landing, and seeking out a suitable field. Finally he put down his battered Hurricane in a meadow near Orpington, and was picked up and rushed to hospital.

________________________________________

F/Lt. Humphrey a’Beckett Russell – (Survived)

F/Lt. Humphrey a’Beckett Russell – (Survived)

Hurricane I V7363

Nearly four miles above the exploding bombs Oberleutnant Ruediger Proske, piloting a Messerschmitt 110 of Destroyer Geschwader 26, dived down to head off a re-attack on the bombers by No 32 Squadron’s Hurricanes.

Squadron Leader Don MacDonell, leading the eight Spitfires of No 64 Squadron, had heard his controller, Anthony Norman, call ‘Bandits overhead!’ (as the low-flying Dorniers of the 9th Staffel swept over Kenley). To MacDonell, orbiting at 20,000 feet, the call seemed a little strange: ‘Instinctively I looked up, but there was only the clear blue sky above me. I thought “My God! Where are they?”‘ Then he looked down and saw a commotion below, too far away from him to work out exactly what was happening. ‘I gave a quick call: “Freema Squadron, Bandits below. Tally Ho!” Then down we went in a wide spiral at high speed, keeping a wary eye open for the inevitable German fighters.’

While MacDonell’s Spitfires were speeding down, the Messerschmitt 110s of the close escort had succeeded in getting between No 32 Squadron and the Dorniers. So Flight Lieutenant ‘Humph’ Russell, 26, shifted his sight on to one of the twin-engined fighters wheeling in front of him. He loosed off a 6-second burst and watched his incendiary rounds ‘walking’ along the fuselage of the enemy aircraft. Several of the German rear gunners replied with accurate bursts, however, and the Hurricane was hit wounding Russell in the left arm and right leg. Smoke began to fill the cockpit so he opened the hood, released his straps and leapt out. Russell’s parachute opened normally but when he looked down he noticed that his leg was bleeding profusely. In his right hand he still clenched the ripcord of the parachute and now he tried to use it as an improvised tourniquet. It was useless: each time he knotted it, the stainless-steel wire simply unravelled itself.

In an air action events follow each other with great rapidity: almost everything described in this narrative, from the time the 9th Staffel had begun its attack on Kenley until now, had taken place within just five minutes: between 1.22 and 1.27 pm on that fateful Sunday afternoon. The only events to continue outside this time span were the longer parachute drops: a man on a parachute falls at about 1,000 feet per minute and Russell, Gaunce, Lautersack and Beck had all baled out from above 10,000 feet.

After his unsuccessful attempt to improvise a tourniquet for his bleeding leg with his ripcord, while hanging from his parachute, ‘Humph’ Russell came to earth beside the railway track just outside Edenbridge. A railwayman working on the line was the first to reach him and, as luck would have it, the man had just completed a course in first aid. Delighted to have a chance to exercise his new-found skill, the man tore strips from the parachute and expertly bound up the wound, Russell was then rushed to the local hospital where he was treated by ‘an excellent doctor who saved my leg, and kept me supplied with Sherry all the time I was in hospital!’

________________________________________

P/O Neville David Solomon (Killed in Action)

P/O Neville David Solomon (Killed in Action)

Hurricane I L1921

As the German aircraft reached the coast near Dover other British squadrons made contact. Here the haze patches were quite thick in places and fighters of both sides blundered about seeking out the enemy. Flight Lieutenant Harry Hillcoat of No 1 Squadron led two other Hurricanes in, to finish off a straggling Dornier of Bomber Geschwader 76; it plunged into the sea off Dungeness. Then one of Hillcoat’s pilots, Pilot Officer George Goodman, spotted a Messerschmitt 110 flying low over the sea, streaming smoke from its left motor; probably it was a fugitive from No 56 Squadron’s snap attack a couple of minutes earlier. Goodman went down after the German fighter, which jinked to avoid his fire but without success. After Goodman’s first burst the left engine caught fire, after his second the right engine followed suit. Then his Hurricane was hit, as a Messerschmitt 109 came round to attack from behind and forced the British pilot to look to his own survival. Goodman hauled his fighter round in a steep turn to the right, and as he did so he caught a glance of the Messerschmitt 110 he had hit striking lie sea. ‘In the turn I made half a mile on the Me 109 and tried to climb in order to bale out, but saw the Me 109 gaining rapidly on me so I pulled the plug and made for home with the enemy aircraft gaining I lightly,’ he later reported. As Goodman pulled up over the coast at Rye the German pilot, probably running short of fuel, broke off the chase.

For 28-year-old Sergeant John Etherington, flying a Hurricane of No 17 Squadron, the business of blocking the German withdrawal seemed rather like standing in the path of a cattle stampede. Enemy aircraft of all types began streaming past, suddenly emerging out of the haze and then disappearing back into it. At first it was not too frightening. ‘As we moved out over the Channel four Messerschmitt 109s passed a little way under us going south. We were there looking for bombers and left them alone; they took no notice of us,’ Etherington recalled. Then Green Section, at the rear of the squadron formation, came under at-link from enemy fighters, followed by Blue Section; Yellow Section broke away to give the others support. That left just Red Section continuing in search of enemy bombers: Squadron Leader Cedric Williams the squadron commander, Etherington, and Pilot Officer Neville Solomon weaving from side to side in the rear guarding their tails. Solomon suddenly disappeared. I never saw what happened to him, nor heard a peep from him. It was his first operational mission and we never saw him again,’ Etherington remembered, ‘so I began weaving from side to side to cover the CO’s tail. There were just two of us, and what seemed like hundreds of enemy aircraft. I thought “How can we possibly get out of this?” And then, suddenly, the CO wasn’t their either.’

Cedric Williams had stumbled upon three Dorniers emerging out of the haze and went in to attack one of them, opening fire at 400 yards and closing in to 250 yards. The Dornier’s left engine caught lire and he saw the bomber dive steeply away. Then, as he was breaking away, Williams saw that he was being attacked by a Messerschmitt 109. He pulled his Hurricane hard round to avoid the enemy fire, and three more Messerschmitts joined in. After a hectic series of diving turns, which took him almost to sea level, Williams succeeded in throwing off the pursuit. The Dornier he had attacked belonged to Bomber Geschwader 76 and one of those on board, war correspondent Hans Theyer, described how the aircraft had been attacked soon after leaving the coast of England: ‘We fired every gun that could be brought to bear, losing off magazine after magazine. Then the “gangster” came in behind our fin, carefully, so that we could not fire at him. He fired some bursts, then turned away.’ With the Dornier’s left motor badly damaged the German pilot, Unteroffizier Windschild, took the bomber down in h steep spiral turn and crash-landed near Calais.

After a frightening few minutes, both Williams and Etherington succeeded in joining up with some of the rest of the Squadron near Dover.

________________________________________

Sgt. Basil E.P. Whall – (Survived)

Sgt. Basil E.P. Whall – (Survived)

Spitfire I L1019 “G”

Dunlop Urie had got the twelve Spitfires of No 602 Squadron off from Westhampnett after the impromptu scramble. Now, in position over Tangmere at 2,000 feet, he suddenly caught sight of a succession of Stukas swooping down on Ford airfield, five miles to the east. Urie pave a quick call ‘Villa Squadron, Tally Ho!’ and led his squadron round to engage the bombers as they pulled out of their dives and passed low over the streets of Middleton-on-Sea and Bognor. Urie himself fired bursts at five of the Stukas before he ran out of ammunition. Sergeant Basil Whall, 21, singled out one of the dive-bombers, made four deliberate attacks on it and saw his tracers striking home. The Stuka curved round towards the coast and Whall watched it go down and make a gentle landing on open ground behind Rustington, not far from the Poling radar station.

Away on the eastern side of the engagement Basil Whall had seen ‘his’ Stuka set down gently beside the radar station at Poling. Then he opened his throttle and swung his Spitfire round to chase after the fleeing dive-bombers, like a hound after hares. He rapidly overhauled Helmut Bode’s Gruppe moving away from Poling and, picking out one of the Stukas, closed in to 50 yards through accurate return fire and put a burst into it. The dive-bomber burst into flames and crashed into the sea. Whall’s Spitfire was also hit, however, and started to trail smoke. Losing height, he hauled the wounded fighter round towards the shore.

From his vantage point at a searchlight on the coast to the east of Middleton-on-Sea, 23-year-old Lance Bombardier John Smith had watched the dramatic fight overhead and the German withdrawal. Then he caught sight of a single aircraft about a mile out to sea, flying west. It turned towards the coast, descending the whole time, then turned again and flew eastwards along the shore line. By now Smith could see that it was a Spitfire, its propeller blades almost stopped and smoke trailing from the engine; the flaps were lowered but the undercarriage was up. Obviously the pilot was bent on setting it down in shallow water. With a splash the aircraft alighted, then the starboard wing struck a submerged groyne. The aircraft leapt back into the air, spun horizontally through a semi-circle, and flopped into the sea going backwards. Smith sprinted down the beach and waded out to the Spitfire, which had come to rest about 20 yards out in waist-deep water. He scrambled on to the wing, to see the dazed pilot still in his cockpit: ‘I could not release the canopy from the outside but in no time at all the pilot opened up, unstrapped himself and with very little assistance from me (in fact I was in his way, if anything) climbed out.’ Sergeant Basil Whall of No 602 Squadron, having accounted for two Stukas and had his Spitfire shot up in the process, was safely down.

References

Franks, Norman L., Royal Air Force Fighter Command Losses of the Second World War – Volume I – Operational Losses: Aircraft and Crews 1939-1941, Midland Publishing, Leicester, England, 2000

Price, Alfred, Battle of Britain: The Hardest Day – 18 August 1940, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, N.Y., 1980

Ramsey, Winston G., The Battle of Britain: Then and Now, After the Battle Magazine, London, England, 1980