[This is one of my earlier – earliest? – posts, having been created in November of 2017. (Tempus fugit, eh?) It’s now updated with additional information and photos.]

________________________________________

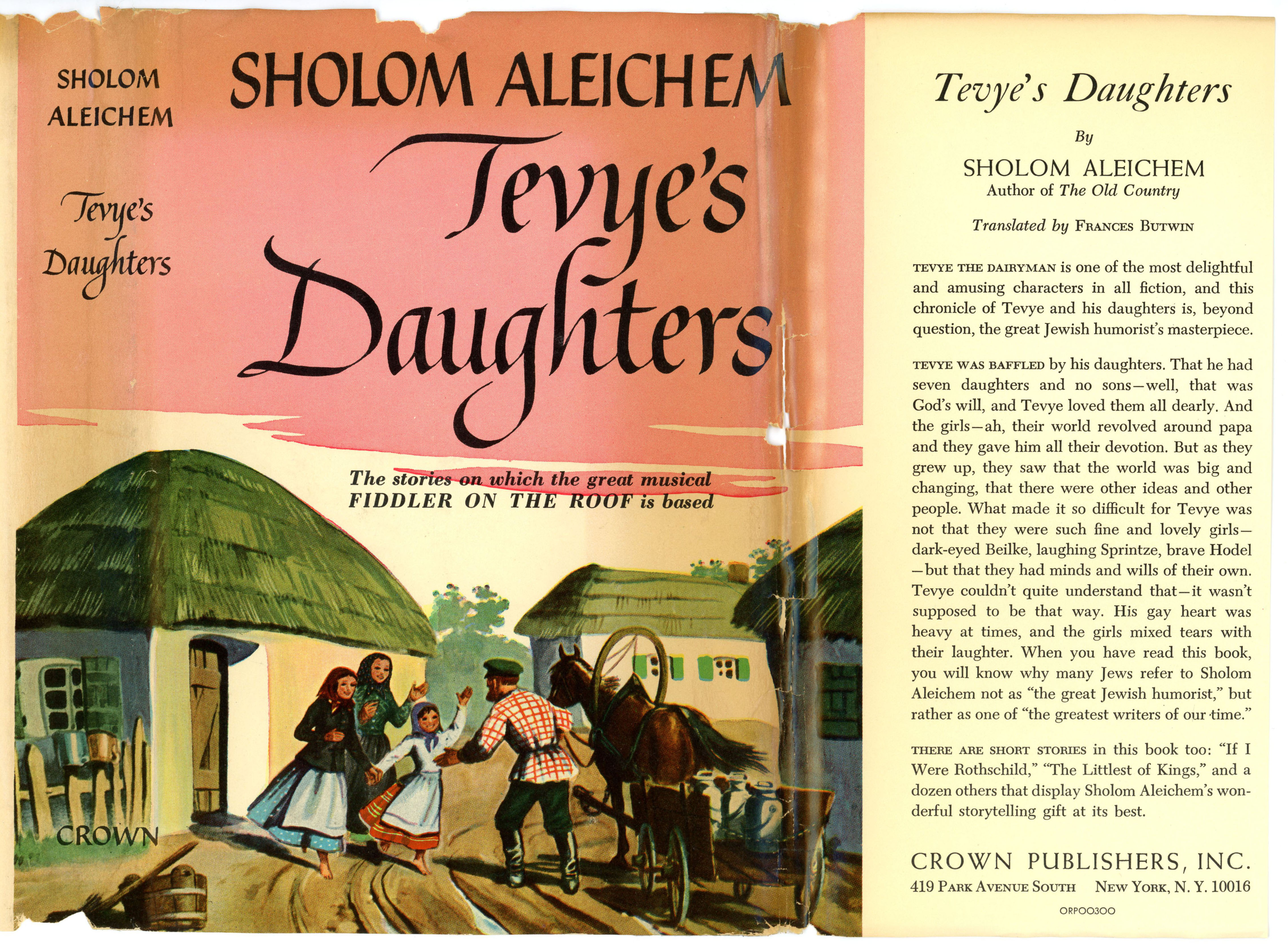

While the artist who created the cover painting for Crown Hill’s 1949 collection of Sholom Aleichem’s tales – published under the title Tevye’s Daughters – is unknown, the translator of the stories is known, her name clearly displayed: She was Frances Butwin.

However, when I first created this post, her name was simply that, “a name”, for I was then unfamiliar with the story of her life as a bibliophile, bookseller, and especially translator of Yiddish. She pursued this latter activity in collaboration with her husband Julius, continuing this work after his sudden death in 1945.

However, when I first created this post, her name was simply that, “a name”, for I was then unfamiliar with the story of her life as a bibliophile, bookseller, and especially translator of Yiddish. She pursued this latter activity in collaboration with her husband Julius, continuing this work after his sudden death in 1945.

Move “forward” (double entendre there…) a few years to June of 2019, I was happily startled to see this image on display at a Facebook post by Washington University’s Stroum Center for Jewish Studies. There, I at long last learned who Frances Butwin was. Or, in the words of the Stroum Center:

“Have you ever read Sholom Aleichem’s stories in English? Chances are, you’ve read the work of translators Frances and Julius Butwin – Professor Joe Butwin’s parents.

A Polish refugee of the Nazis and a child of Russian Jewish émigrés, Frances and Julius met through the pages of The Forward, through an essay contest titled “I am a Jew and an American.”

After 4,000 pages of correspondence, the couple married, and became some of the very first translators of Sholom Aleichem’s work into English – before Julius’ tragic early death at age 41.

Professor Joe Butwin of UW English Department shares his parents’ remarkable story, and discusses his own career as an advocate for Yiddish and Jewish literature at the UW, in a profile by Denise Grollmus.”

You can learn much more about the lives of Frances and Julius Butwin in Denise Grollman’s article “Professor Joe Butwin reflects on how his academic career always led him back to his family roots“, which includes two images of the couple (shown below), as well as images of Professor Butwin, Aharon Appelfeld, and Abraham Lincoln Brigade veteran Ed Lending.

“Julius and Frances Butwin in Wisconsin Dells, Wi., shortly after their marriage in 1933.”

“Julius and Frances Butwin in Wisconsin Dells, Wi., shortly after their marriage in 1933.”

____________________

“Frances Butwin at a book signing for her and Julius’s translation of Sholom Aleichem’s “The Old Country,” alongside author John Bennet, 1946.”

“Frances Butwin at a book signing for her and Julius’s translation of Sholom Aleichem’s “The Old Country,” alongside author John Bennet, 1946.”

You can learn more about the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies here, and, follow the Center on Facebook, here.

________________________________________

Reading about the lives of the Butwins and their literary endeavors sparked my curiosity (not a hard thing to spark, I suppose). To that end, the three following book reviews – one from The Philadelphia Inquirer by Mortimer J. Cohen, and two from The New York Times (by Orville Prescott and Thomas Lask) – present views of the Butwin’s work from the perspective of mainstream American literary culture during the late 1940s. A fourth item – Sheldon Harnack’s 1972 essay in the (New York) Daily News – delves into Jerry Bock, Joe Stein, and Harnack’s use of the stories in Frances Butwin’s translation of Tevye’s Daughters as the basis for a certain musical known as “Fiddler On The Roof”.

Harnack’s comment about his difficulty is locating a copy of Butwin’s book (in New York City, of all places) is as ironic as it is charming: “Incredibly, this classic was out of print and it was very difficult to locate two extra copies. We did manage to find one copy, unexpectedly, in a bookstore whose specialty was religious literature – mostly Catholic, at that – an irony I’m sure Sholom Aleichem would have relished.”

Well, I discovered my own copy (cover displayed above) at a used Bookstore in Atlanta, Georgia. So, there you go!

As for Lask’s review? Like many reviews in the Book Review section of the Sunday Times, it’s accompanied by an illustration: in this case, an imagined view of our hero Tevye. Very (very!) close inspection of the drawing reveals that the artist’s name is “B. Gumener Nutkiewicz”, who I’m certain is Betty Gumener Nutkiewicz, a 1947 graduate of the Wayne State University Art Education Department and wife of N. Nutkiewicz, one of the editors of the Detroit edition of the Forward, as described in The Jewish News (Detroit) on June 23, 1950.

________________________________________

Books of the Times

By ORVILLE PRESCOTT

The New York Times

June 24, 1946

THE OLD COUNTRY. By Sholem Aleichem. Translated by Julius and Frances Butwin. 434 pages. Crown. $3.

SHOLEM ALEICHEM, who was born in Pereyeslav in the Ukraine in 1859, died in Brooklyn in 1916. Although he is unknown to most of the world, he is generally considered to have been one of the greatest of all Yiddish writers. More than a million copies of his books have been sold. His collected works comprise twenty-eight volumes. It is told of him that when he first came to New York Mark Twain went to call upon him. “I wanted to meet you,” he said, “because I understand that I am the American Sholem Aleichem.” Of his grand total of 300 short stories twenty-seven may now be found in “The Old Country,” translated into English for the first time by Julius and Frances Butwin.

Yiddish literature is unknown territory to most of us. Little of it has been translated, and some of that little has proved of limited appeal. Today Sholem Asch’s great religious novels about Christ and St Paul, “The Nazarene” and “The Apostle,” are the only Yiddish works known to most readers even by name. Much more representative, I presume, was Sholem Aleichem, who, wrote of his own people as he had known them in the Jewish villages of imperial Russia. The stories he tells of them are very similar to another notable Yiddish work which was published here last September, “Song of the Dnieper,” by Zalman Shneour. It is quite possible that Mr. Shneour was influenced by the elder writer. But he was also obviously influenced by the literary and political atmosphere of a later generation. There is far more violence, misery, corruption and ignorance in “Song of the Dnieper” than in “The Old Country.”

Stories Are Simple and Colloquial

Sholem Aleichem would be called a regional writer if we could transplant that word to a foreign literature. His stories sometimes are intricately plotted, and some of them present well-individualized characters; but the first concern of them all seems to be atmosphere, the habits of thought and turns of speech, the customs and superstitions of a special way of life. With humor and affection and zest Aleichem wrote of the villagers of Kasrilevka and Zolodievka, their poverty, their religion, their loquacity and their unconquerable delight in wit and learning. The Jews of Old Russia, as Aleichem saw them, were devout and honorable, simple in a tunelessly provincial fashion and at the same time emotionally sophisticated.

Nobody could be more humbly fatalistic than the man who contemplated his poverty and the riches of others and sighed, “If it should have been different it would have been.” Slightly more cynical was a subsequent thought, “to some people butter rolls, and to others the plague.” But fleshly comforts are not to be scorned either. “God is God, but whisky is something you can drink.”

These stories are written in a simple, colloquial style as if their author were one of the villagers spinning a tale about his neighbors. The matter, too, as well as the manner, contributes to the general folk air. Holy days and festivals, marriages and deaths, drunkenness and barter, the hazards of various occupations, these are Aleichem’s themes. They are more important than the characters themselves. This is the way it was in the old country, he seems to be saying. This is the way the people lived and died. And, most important of all, this is the way they talked. “The Old Country” is filled with marvelous talk that has survived the perils of translation surprisingly. The special rhythms of Yiddish speech, the dependence on quotation and allusion, the sly wit, are all wonderfully well conveyed. Those who know Aleichem’s work in the original may have other ideas, but this book is not intended for them.

One Hero Is Dogged by Bad Luck

Much the most interesting character in “The Old Country” is Tevye, the hero of several stories which he tells in the first person. Tevye was a shlimazl, a man dogged by bad luck. Tevye’s idea of a cheerful greeting to strangers was “What is it you want? If you want to buy something, all I have is a gnawing stomach, a heart full of pain, a head full of worries, and all the misery and wretchedness in the world.” Tevye was usually down, but never out. He was colossally ignorant, but he prided himself on his learning. He tried to seem fierce, but he had the kindest heart in the village. He loved to talk and to misquote and merely to live, although he knew few enough of the pleasures of life. Tevye is a humorous triumph.

But his presence makes many of the other stories in “The Old Country” seem somewhat insipid in comparison. No matter how authentic it may be, local-color writing soon palls. No matter how adroit and understanding, fiction on the folk level soon becomes tedious. After a few stories in “The Old Country” one is inclined to think, “how delightful!” After a good many one is likely to be bored and fretful. Charm and atmosphere aren’t enough. Something more substantial into which he, the reader, can set his teeth is needed, some ideas, some deeper penetration into character, some more adult storytelling. “The Old Country,” by ignoring Russia and the Russians, doesn’t even have anything to say about that other aspect of life in the old country, the aspect which sent so many Jews fleeing to other countries.

There can be no question that Sholem Aleichem was an accomplished writer. Whether he wrote the kind of fiction that will appeal widely to non-Yiddish readers is another matter.

________________________________________

Humor That Is Poignant

TEVYEH’S DAUGHTERS. By Sholom Aleiehem. Translated by Frances Butwin. 302 pp. New York: Crown Publishers. $3.

By THOMAS LASK

The New York Times

January 23, 1949

SO appealing, so warm and quick with life are the writings of Sholom Aleichem that he has stimulated translators all over the world. His work has appeared in such various tongues as Lettish, Esperanto and Japanese. Although an early translation in English came out in 1912, only six volumes have appeared altogether, and these of uneven merit. Today, though he remains a major literary figure, the number of those who can read him in the Yiddish original has become steadily fewer. Thus, Mrs. Butwin, who with her husband brought out a previous book of stories, “The Old Country,” in telling the story of Tevyeh and his daughters, has performed a major service. Tevyeh is company too good to be barred from us by foreign syllables.

But even to so expert a workman as Mrs. Butwin there must be a large element of frustration in this enterprise, for she surely knows better than others how difficult it is to get that picturesque, flavor-some, idiomatic folk tongue into equivalent English speech. Yet it is precisely his handling of this folk language that sets off his greatness. Sholom Aleichem could fashion an effective short story as well as the next one; but in his use of the common Yiddish speech he stands alone. It is both the substance and the medium, and he has wedded it to characters who raised dialect to the stature of art. These were the Jews of the Russian pale who flourished before the holocaust and who were so poor that the spoken word was their only permanent possession. Their poverty was a function of their lives, and “they raised it to “an art, a calling, a career.” But through their speech they squared themselves with their condition, their assorted misfortunes, even with the Almighty Himself. As Maurice Samuel has remarked, life got the better of them, but they got the better of the argument.

But if Mrs. Butwin’s stories are not the equal of the originals (and she would be the last to claim that they are), there is still a great deal that is amusing and delightful. Her versions are always mellifluous, and at least two of the stories can be recommended without qualifications. In “Another Page From the Song of Songs,” she has caught the tender wistfulness of a spring day; and in “Schprintze” she has retained the melancholy that was a quality of the original.

Moreover, Mrs. Butwin has had the intelligence to concentrate on one of the most popular and effective of Sholom Aleichem’s portraits, Tevyeh the Dairyman. Tevyeh had two major afflictions: his livelihood (or lack of one) and his seven marriageable daughters. No matter how he contrived or plotted to arrange suitable marriages, the girls had minds of their own and insisted on making their own destiny – with lamentable results. One spurns a rich man and marries a poor tailor who dies and bequeaths her a roomful of children. Another insists on marrying a revolutionary and sharing his exile. A third marries a Christian, and Tevyeh cuts the apostate from his life if not his heart. One, finally, does marry a rich magnate from Yehupetz, but this is the worst marriage of all – for money has been substituted for love and pride. In spite of his outward show, Tevyeh admires their independence. Throughout it all he struggles with his poverty, fences and argues with his wife, curses and communes with his nag and hides his sorrow.

ALL this may not seem the raw material for comedy, yet Tevyeh is one of the great humorous figures in literature. He has become so from his wit, from the play of his mind on the events, from his intellectual sprightliness. He is irrepressible. For every situation he has the quotation or twist of phrase that redeems it. His humor doesn’t derive from the situation, but from the language that applies to it. It is a bittersweet optimism that is found so frequently in Sholom Aleichem’s writings. It can be seen in the note that Yosrolik writes to his friend after the Kishinev massacre: “Pogrom? Thank God we have nothing to fear. We have already had two of them and a third won’t be worth while.”

ALL this may not seem the raw material for comedy, yet Tevyeh is one of the great humorous figures in literature. He has become so from his wit, from the play of his mind on the events, from his intellectual sprightliness. He is irrepressible. For every situation he has the quotation or twist of phrase that redeems it. His humor doesn’t derive from the situation, but from the language that applies to it. It is a bittersweet optimism that is found so frequently in Sholom Aleichem’s writings. It can be seen in the note that Yosrolik writes to his friend after the Kishinev massacre: “Pogrom? Thank God we have nothing to fear. We have already had two of them and a third won’t be worth while.”

Mrs. Butwin has also included a few stories which depend for their effect on their narrative qualities. “The German,” in which a cheated traveler takes a long and subtle revenge, would fit very well in any contemporary collection; and “Gymnasia,” a passionate parent’s plan for her son’s education, is a study in organized chaos. And there are a number of other tales that reveal indirectly the ramshackle, confined towns and life in the pale – and in the distance the movement and mutter of the outside world that was already stirring, not only to destroy this life, but also the people who lived it.

________________________________________

Eternal Clash of New and Old

TEVYE’S DAUGHTERS, BY Sholom Aleichem, Crown Publishers: New York, 302 pp. $3.

The Philadelphia Inquirer Book Review

February 27, 1949

By Mortimer J. Cohen

TEVYE the Dairyman is the main hero of this volume of short stories by the great Yiddish writer, Sholom Aleichem.

Tevye is the symbol of a world that has passed away, a world that had its physical locale in the Russian-Polish Pale of Settlement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but whose real foundations were in the hearts of a great Jewish community now destroyed by Hitlerism.

Undoubtedly Sholom Aleichem, who has been favorably compared to our American Mark Twain, intended to write a family chronicle in these tales about the seven daughters of Tevye, who circle about him like planets around the sun. Among the planets, of course, moves Golde, Tevye’s beloved wife. Through all the stories runs a single theme: “The never-resolved conflict between the younger and older generations.”

TEVYE, who sells milk, butter and cheese to the folks of the neighboring towns for a living, is a man of simple piety whose deep religious faith enables him to meet the challenge of poverty, trial and sorrow.

Tevye’s “old-fashioned” ideas are strongly challenged by the stormy times in which he lives: the last days of Czarist Russia with its political unrest and the revolutionary struggle of 1905-6.

Within Jewry at the time strong ferments are at work: Zionism and the spread of secular culture through the Haskalah, or Enlightenment.

Tevye’s daughters are infected by these currents and counter-currents, and they in turn rebel against Tevye and Golde and the patriarchal way of life they represent.

But Tevye loves his daughters, whom he considers the most beautiful creatures in the world, and he even finds ways to justify them, blaming their actions upon “an evil fate” which they cannot control.

THROUGH all his experiences, Tevye remains patient, profoundly human, compassionate, understanding and lovable. His humor lights up the dark places he travels through. And to the very end he is sustained by his religious faith.

Not all the stories in this volume deal with Tevye and his daughters. The translator, Frances Butwin, who has done a superb job, has intertwined the chronicles of Tevye the Dairyman with the other stories in such a way that the latter become interesting not only in themselves but as backgrounds.

This is an admirable volume of stories that will bring smiles and tears to the reader.

________________________________________

Book Is the Thing in ‘Fiddler’

Daily News (New York)

June 11, 1972

Around 1940, when I was in my 2nd or 3rd year at Chicago’s Carl Schurz High School, my friends and I stumbled on the work of Bob Benchley. Talk about serendipity!

After devouring everything of his we could lay our hands on, in rapid succession we went on to revel (wallow might be a better word) in the heady concoctions of S.J. Perelman, James Thurber, Stephen Leacock and a few other dispensers of “wonderful nonsense.” Knowing that I was hooked on this type of humorous writing, a friend recommended that I try Sholom Aleichem, the alleged “Yiddish Mark Twain.”

I remembered having seen “The Old Country” Country” among my father’s books. So I read it. (It was in English: I couldn’t read Yiddish then and, regrettably, still can’t.) I didn’t like it; that is, although the stories were not without interest I didn’t find it funny in the way Benchley, Perelman, et al, were funny. I was looking for that particular kind of screwball humor, that verbal dexterity which characterized my favorites. Sholom Aleichem, I decided, wasn’t even in the same league. I never even thought to ask myself whether he had lost something in translation.

Looking for an Idea

Cut to 20 years later. Jerry Bock and I are looking for a suitable subject for a musical. A friend suggests Sholom Aleichem’s “Wandering Star.” I, secure in the wisdom of the conclusion reached when I was 15 or 16 years old, can be heard asserting to Jerry, “Well, let’s not expect too much. I read some stuff of his years ago and it wasn’t so hot.”

So we read the book. Of course, by this time I was no longer in frenzied pursuit of hilarious literary outbursts. We were looking for a story rich in emotion, peopled with the sort of characters who might be legitimately expected to burst into song. “Wandering Star” had all of that in abundance.

Well, Jerry and I were so taken with the novel that we asked Joe Stein to read it. Joe liked it as much as we did but pointed out that there was too great an abundance of just about everything in it. He doubted that it could be pared down and molded into manageable theatrical shape. Joe, who was familiar with other Sholom Aleichem works (and in Yiddish, yet!) suggested that we explore more of his stories. He smiled as he recalled how funny some of them were. I nodded skeptically. I knew better.

Not long after this we discovered “Tevye’s Daughters” (I think Joe may have owned a copy) and knew that we wanted to try to translate it to the stage. Incredibly, this classic was out of print and it was very difficult to locate two extra copies. We did manage to find one copy, unexpectedly, in a bookstore whose specialty was religious literature – mostly Catholic, at that – an irony I’m sure Sholom Aleichem would have relished.

Begin Studying

So, the three of us began to study the various stories that comprise Tevye’s Daughters (in the Frances Butwin translation). As far as I know, these stories were not written to form one continuous novel; each was written as a self-contained entity and they are scattered through several collections of miscellaneous tales. The largest number of them in any single volume is in the book entitled “Tevye’s Daughters,” which also includes “The Little Pot,” an initially amusing but ultimately heartbreaking story narrated by a character named “Yenta.” As I read the- stories over and over, literally immersing myself in them, a startling thing happened. To paraphrase Mark Twain’s celebrated comment concerning his father, it was amazing how much Sholom Aleichem’s writing had improved in 20 years!

Since the narrative style of “Tevye’s Daughters” is simple and straightforward (deceptively so), the beauty and the intensely moving quality of the stories is apparent on a single reading. Repeated

readings began to reveal the subtleties of his writing, as well as the extraordinary depth of his knowledge and understanding of his characters. And the more we understand these characters, how richly human they were, the funnier and sadder they became.

More Than Ethnic

We also began to realize that the humor, the pathos, the humanity, and the meaning of these stories went far beyond any ethnic frame or any tour-de-force of mere verbal dexterity. Sholom Aleichem may have been writing specifically for a Yiddish speaking audience,-but his is an eloquence that far transcends language.

To state, as did Irving Howe in his review of “Fiddler” in “Commentary” that “The action in his stories tends to be slight, for everything rests on language, a kind of rippling monologue in which the full range of nuances is available only to the cultivated Yiddish reader,” is to glorify style at the expense of the universality which we found so profoundly moving. It was this we worked so hard, under Jerome Robbins’ loving and scrupulous supervision, to re-create on the stage.

Because of the immensity of “Fiddler’s” success and the resultant vast amount of publicity the show has received, I find that (speaking for myself) there is a tendency to accept my share of the credit and praise and let Sholom Aleichem’s monumental achievement slide quietly into the background. Oh, yes, we always mention his name in passing but that’s about all. Now that “Fiddler” is about to become the longest running show in Broadway’s history, I feel an obligation to set the record straight. If you put all of us who put “Fiddler” together on one side of a balance, and Sholom Aleichem along with his inspired creation: Tevye and his world, on the other, the balance would quickly tip in Sholom Aleichem Tevye’s direction.

I only wish that everyone who has seen “Fiddler” and enjoyed it would buy, rent, or borrow a copy of “Tevye’s Daughters” (now back in print, one of the nicer spin-offs from the show’s success) and read all the “Tevye” stories. After all, we only used four of them, and have no intention of writing either “Son of Fiddler” or “The Further Adventures of Tevye and his Daughters.” Go, read.