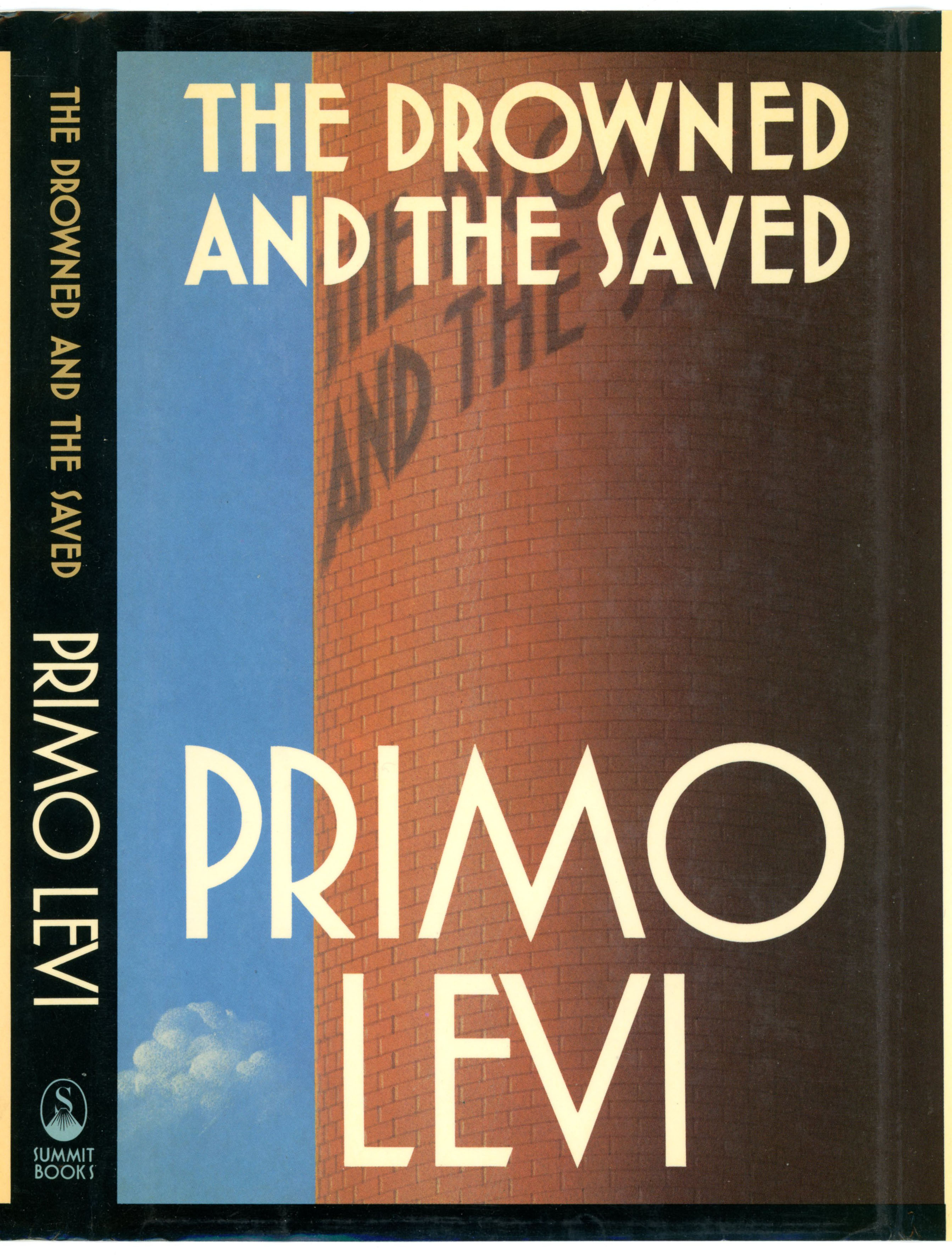

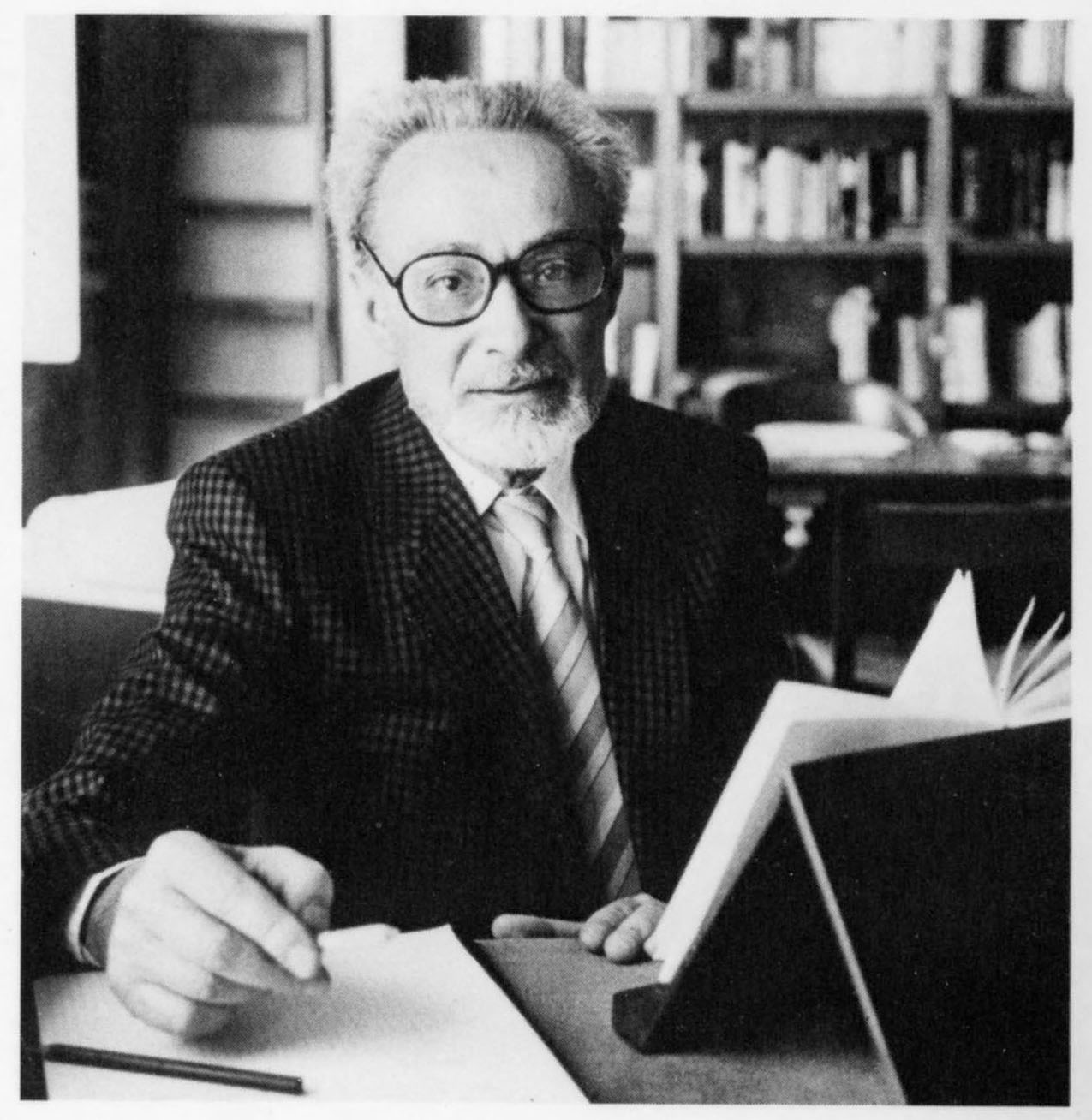

This is one of my earlier posts. It displays Fred Marcellino’s cover art for Summit Books’ 1988 edition of Primo Levi’s The Drowned and The Saved, and includes -paralleling Summit Books’ edition of Primo Levi’s The Monkey’s Wrench – a portrait of author Levi, probably (it looks like…) at his home, in Turin, Italy. Given that Mr. Levi was wearing the same suit and tie in two different portraits, the images were probably taken within a single session by photographer Jerry Bauer.

The post now includes John Gross’ review of The Drowned and The Saved, which appeared in The New York Times – the main paper, not the Book Review – in January of 1988, and includes a less formal portrait of Primo Levi by a photographer from La Stampa, Cesare Bosio.

Though the nature of Marcellino’s cover art isn’t immediately apparent – red bricks and a blue sky? – “stepping back”, it soon becomes clear that he has depicted a chimney, a terrible, and terribly appropriate, symbol of Levi’s subject matter. In this respect, reviewer Gross has admirably presented the central aspects, or more appropriately questions, of the book, which focus on the challenge (or near-impossibility) of communicating that-which-cannot-be-communicated; the fallibility of memory – whether that memory be personal or historical; and particularly, the “gray zone” in which prisoners of the German concentration camp system found themselves enmeshed.

I think it quite fitting that Gross ends his review of The Drowned and The Saved with the very verse (from Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s The Rime of The Ancient Mariner) with which Primo Levi opened the book:

Since then, at an uncertain hour,

That agony returns,

And till my ghastly tale is told

This heart within me burns.

(Photograph of Primo Levi by Jerry Bauer)

(Photograph of Primo Levi by Jerry Bauer)

Books of The Times

By John Gross

THE DROWNED AND THE SAVED. By Primo Levi.

Translated from the Italian by Raymond Rosenthal.

203 pages. Summit Books. $17.95.

The New York Times

January 5, 1988

Photograph by Cesare Bosio (La Stampa)

Photograph by Cesare Bosio (La Stampa)

IF you are a writer, and you have come back from hell, you really only have one subject. It may be important for you to write about other subjects, too, in order to show that hell doesn’t have the last word; and yet in the end there is no shedding your burden. In some of his later books Primo Levi moved away from the agonies of the Holocaust, but it was to the Holocaust that he finally returned.

“The Drowned and the Saved,” which Mr. Levi completed shortly before his death last April, is a series of meditations on some of the more perplexing aspects of “the Lager phenomenon” – the world of the extermination camps. Like all Mr. Levi’s books, it is distinguished by courage, lucidity and intelligence, by a steadfast honesty and a refusal to take refuge in the consolations of rhetoric.

The guards and the prisoners in the camps had at least one thing in common. Both groups knew that by the standards of the outside world, what they were taking part in was incredible. Even if someone lived to tell the tale, who was going to believe him?

An agreeable thought for the tormentors, and a source of despair for their victims. Most survivors, Mr. Levi tells us, can recall a recurrent dream that afflicted them during their nights of imprisonment: “They had returned home and with passion and relief were describing their past sufferings, addressing themselves to a loved one, and were not believed, indeed were not even listened to.”

In the event, the Nazis failed – not for want of trying – to destroy all the evidence and wipe out all the witnesses. Yet as a relatively “privileged” prisoner, spared the worst on account of his usefulness as a scientist, Mr. Levi felt strongly that the full horrors would never be known, since almost all firsthand descriptions of the camps are the work of “those who, like myself, never fathomed them to the bottom.” By contrast, very few “ordinary” prisoners survived, and very few of those who did, paralyzed as they were “by suffering and incomprehension,” were able to offer more than fragmentary testimony.

None of this made it less important, in Mr. Levi’s eyes, to bear witness as best he could. There were the tricks that memory plays that had to be guarded against, for one thing – and the tricks we play on memory. These can be seen at their most glaring in the case of the Nazi killer who “doesn’t remember” what he did: “The rememberer,” as Mr. Levi says, “has decided not to remember and has succeeded.” But among victims, too, though for very different reasons, the past is readily refashioned; indeed, Mr. Levi’s observations in Auschwitz had shown him that “for purposes of defense, reality can be distorted not only in memory but in the very act of taking place.”

Between them, defective memories and defective understanding have given rise to the stereotypes that Mr. Levi was anxious to clear away. The one that he deals with at greatest length, and that raises the most sensitive issues, is the notion that relationships in the camps could be reduced to a simple contrast between oppressors and oppressed, that every prisoner was a victim and nothing but a victim.

Anyone who supposes this has a very inadequate idea of how monstrous the whole system was. For it was an essential aim of the Nazis to destroy their victims morally as well as physically, to implicate them and drag them down. At the most extreme, there were the special squads of prisoners given the job of running the crematories: organizing such squads, in Mr. Levi’s view, was “National Socialism’s most demonic crime.” But there were many other levels of “privilege,” and immense pressures to take advantage of fellow prisoners in order to cling to life or gain a respite from pain.

Mr. Levi gives an eloquent account of “the gray zone” in which prisoners were set against one another, beginning with the blows from “privileged” prisoners that greeted and utterly disoriented new arrivals. He doesn’t perhaps allow enough for the fact that some people are bound to seize on the existence of such a zone as an excuse for indulging in the comfortable game of “blame the victim,” but his own reactions are as nuanced and undogmatic as the situation demands. He never loses sight of where the primary responsibility for Auschwitz lay, and he knows that a gray zone calls for gray judgments.

He is particularly good, too, on the sense of shame that overcame prisoners, and on the “unceasing discomfort that polluted sleep and was nameless.” It would be absurd, he says, to call this last a neurosis; it was more like the “tohu-bohu” of Genesis, the meaninglessness of a universe from which the spirit of man was absent.

Other topics he discusses include the situation of the intellectual prisoner, the reactions of German readers to his books and what “communicating” meant amid a babel of languages, where many prisoners understood little or nothing of the commands they were receiving. (At one camp, a rubber truncheon was called “the interpreter.”) Reflecting on the violence and oppression that still abound in the world, he doesn’t rule out the possibility that something comparable to the Holocaust could happen again – indeed, he reminds us that in Cambodia, it already has.

At the beginning of “The Drowned and the Saved,” Mr. Levi quotes a verse from “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner”:

Since then, at an uncertain hour,

That agony returns,

And till my ghastly tale is told

This heart within me burns.

Extremely powerful in themselves, these lines somehow become even more powerful in the new context he gives them. But it isn’t only a ghastly tale that he offers; in telling it, he also provides a heroic example of humane and civilized understanding.

March 9, 2018