The them of parallel worlds has long been prominent in science-fiction and fantasy, with some works – such as Poul Anderson’s entrancing “Three Hearts and Three Lions” (published as a novella in the September, 1953 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction) combining these themes to marvelous and entertaining effect. As vastly more of a devotee of science-fiction than fantasy, I was truly impressed by Anderson’s story, particularly in terms of world-building, pace of action, the refreshing delineation and individuation of characters, and the subtle undercurrent of pathos that courses through the tale.

An earlier embodiment of this dual-genre – “science-fantasy” – is L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt’s “The Roaring Trumpet”, which appeared in the May, 1940 issue of Unknown. Like the Anderson tale, “Trumpet” has a lengthy entry at Wikipedia. Therein, it’s revealed that the story is the first of the five Harold Shea stories penned by the dual authors, which – albeit Wikipedia’s a little confusing on the point! – comprise the “Incomplete Enchanter” series which, together with the complimentary “Complete Enchanter” series, form the – ahem, wait for it… “Enchanter” series. (I think I got it right!)

And yet…

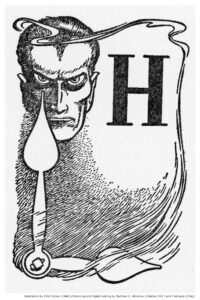

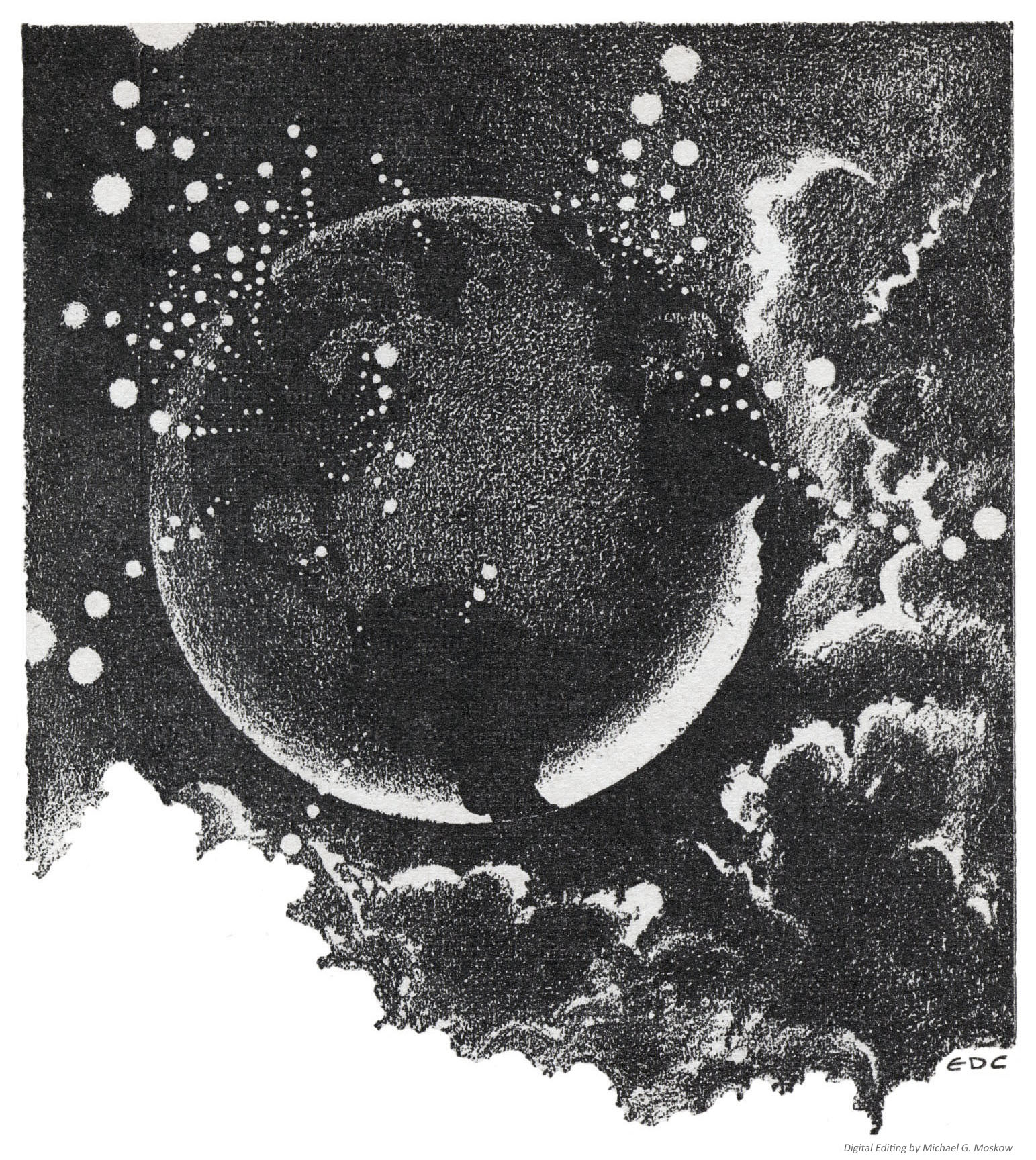

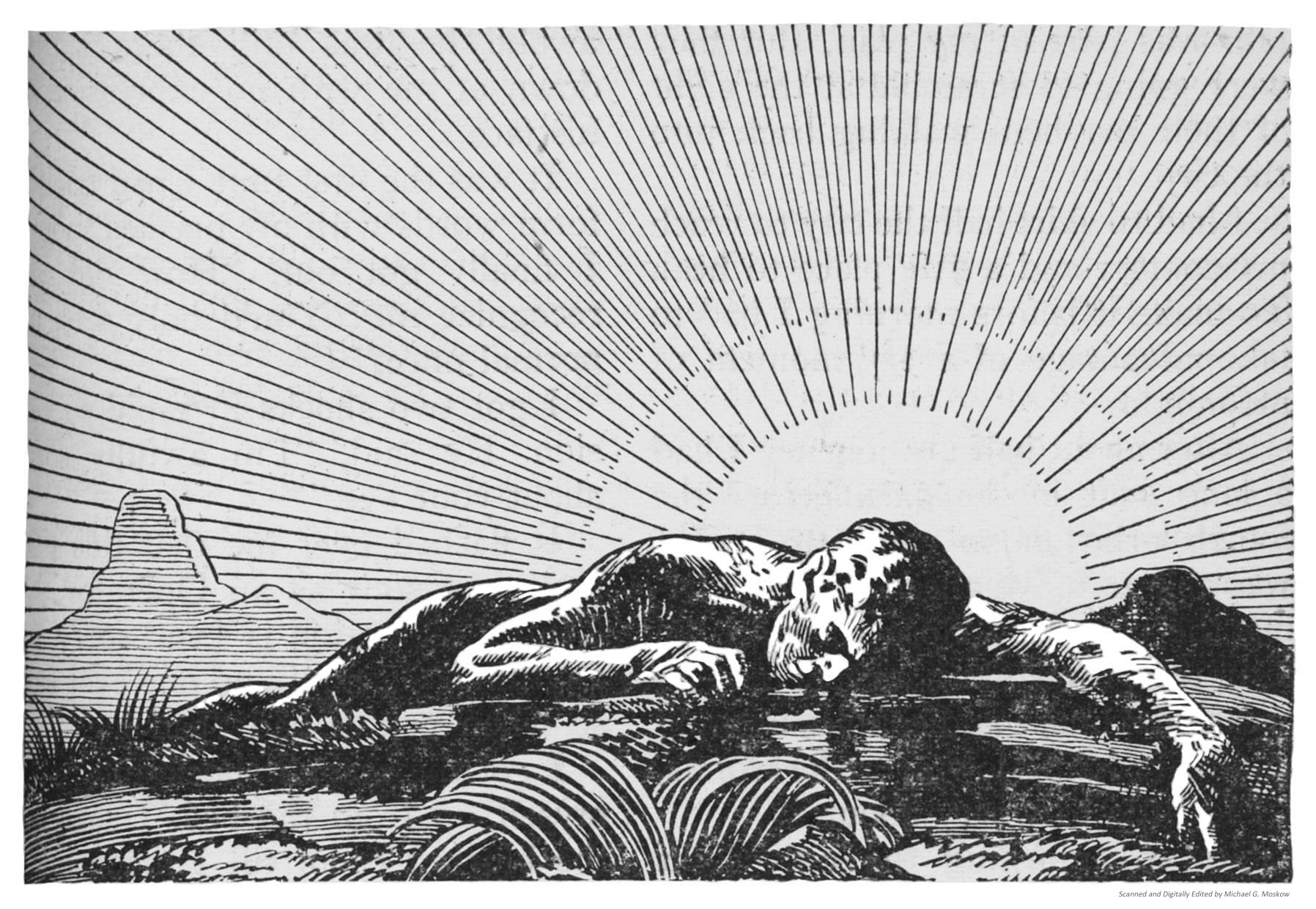

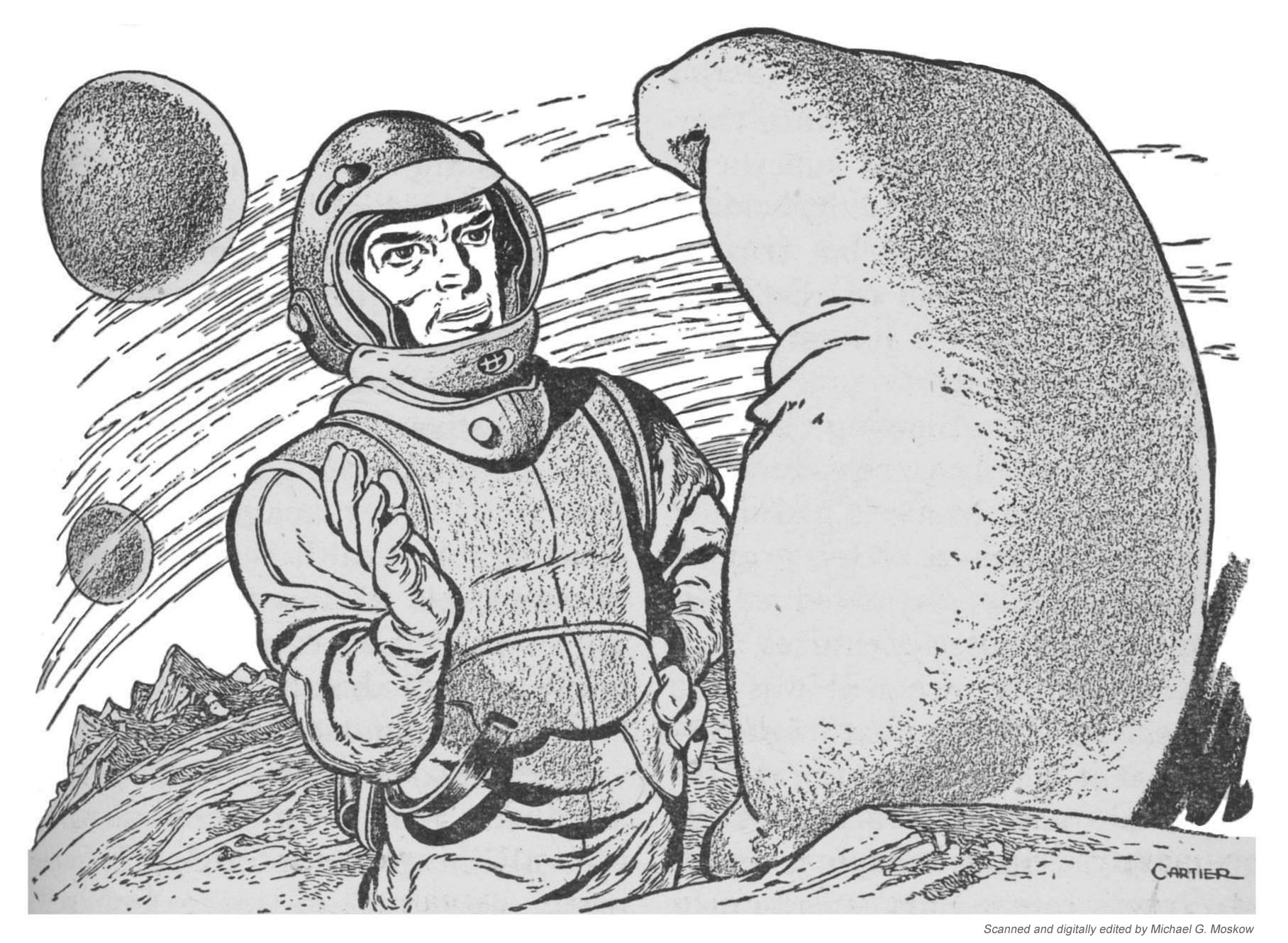

True confession!… I’ve not actually read “The Roaring Trumpet”. Rather, I discovered the story by not-so-randomly perusing Unknown at Archive.org in order to view the illustrations that appeared in the magazine during its late ’30s – early 40s existence. I was (I remain) especially taken by Edd Cartier’s illustration on page 17, which depicts the first (and random, though instrumental to the story!) meeting between the unknowing protagonist Harold Shea and Odinn, who as drawn by Cartier has an incredible Ian McKellen-ish / Gandolf-ish “vibe” about him.

(On first perusal, before I actually read about and skimmed the story, I assumed that Shea had chanced across a wizard or warlock. What, with the long, gaunt and cloaked figure; the lengthy black cloak; the hoary, untrimmed beard; the look of annoyed detachment (with compassion underneath). “Ah-hah,” I imagined, “it’s Gandolf’s ne’er do well half-brother Blandolf, making an appearance in the world of human myth!”)

Here’s how their encounter went down:

“Welcome to Ireland!” Harold Shea murmured to himself, and looked around. The snow was not alone responsible for the grayness. There was also a cold, clinging mist that cut off vision at a hundred yards or so. Ahead of him the track edged leftward around a little mammary of a hill, on whose flank a tree rocked under the melancholy wind. The tree’s arms all reached one direction, as though the wind were habitual; its branches bore a few leaves as gray and discouraged as the landscape itself. The tree was the only object visible in that wilderness of mud, grass and fog. Shea stepped toward it and was dumfounded to observe that the serrated leaves bore the indentations of the Northern scrub oak.

But that grows only in the Arctic Circle, he thought, and was bending closer for another look when he heard the clop-squash of a horse’s hoofs on the muddy track behind him.

He turned. The horse was very small, hardly more than a pony, and shaggy, with a luxuriant tail blowing round its withers. On its back sat a man who might have been tall had he been upright, for his feet nearly touched the ground. But he was hunched before the icy wind driving in behind. From saddle to eyes he was enveloped in a faded blue cloak. A formless slouch hat was polled tight over his face, yet not so tight as to conceal the fact that he was both full-bearded and gray.

Shea took half a dozen quick steps to the roadside and addressed the man with the phrase he had carefully composed in advance for his first human contact in the world of old Ireland:

“The top of the morning to you, my good man, and would it be far to the nearest hostel?” He had meant to say more, but paused a trifle uncertainly as the man on the horse lifted his head to reveal a proud, unsmiling face in which the left eye socket was horribly vacant. Shea smiled weakly, then gathered his courage and plunged on: “It’s a rare bitter December you do he having in Ireland.”

The stranger looked at him. Shea felt; with much of the same clinical detachment he himself would have given to an interesting case of schizophrenia, and spoke in slow, deep tones: “I have no knowledge of hostels, nor of Ireland; but the month is not December. We are in May, and this is the Fimbulwinter.”

A little prickIe of horror filled Harold Shea, though the last word was meaningless to him. Faint and far, his ear caught a sound that might be the howling of a dog – or a wolf. As he sought for words there was a flutter of movement. Two big black birds, like oversize crows, slid down the wind past him and came to rest on the dry grass, looked at him for a second or two with bright, intelligent eyes, then took the air again.

“Well, where am I?”

“At the wings of the world, by Midgard’s border.”

“Where in hell is that?”

The deep voice took on an edge of annoyance. “For all things there is a time, a place, and a person. There is none of the three for ill-judged questions and empty jokes.” He showed Shea a blue-clad shoulder, clucked to his pony and began to move wearily ahead.

“Hey!” cried Shea. He was feeling good and sore. The wind made his fingers and jaw muscles ache. He was lost in this arctic wasteland, and this old goat was about to trot off and leave him stranded. He leaped forward, planting himself squarely in front of the pony. “What kind of a runaround is this, anyway? When I ask someone a civil question-”

The pony had halted, its muzzle almost touching Shea’s coat. The man on the animal’s back straightened suddenly so that Shea could see he was very tall indeed, a perfect giant. But before he had time to note anything more he felt himself caught and held with an almost physical force by that single eye. A stab of intense, burning cold seemed to run through him, inside his head, as though his brain bad been pierced by an icicle. He felt rather than heard a voice which demanded, “Are you trying to stop me, niggeling?”

For his life. Shea could not have moved anything but his lips, “N-no,” he stammered. “That, is, I just wondered if you could tell me how I could get somewhere where it’s warm-”

The single eye held him unblinkingly for a few seconds. Shea felt that it was examining his inmost thoughts. Then the man slumped a trifle so that the brim of his hat shut out the glare and the deep voice was muffled. “I will be tonight at the house of the bonder Sverre, which is the Crossroads of the World. You may follow.” The wind whipped a fold of his blue cloak, and as it did so there came, apparently from within the cloak itself, a little swirl of leaves. One clung for a moment to the front of Shea’s coat. He caught it with numbed fingers, and saw it was an ash leaf, fresh and tender with the bright green of spring – in the midst of this howling wilderness, where only arctic scrub oak grew!

L. Sprague de Camp

“A weird and tingling chill bore into Shea’s mind

as the old man’s single eye glared down at him…”

(page 17)

And otherwise…

“The Roaring Trumpet”, at ...

… Wikipedia (has detailed plot summary)

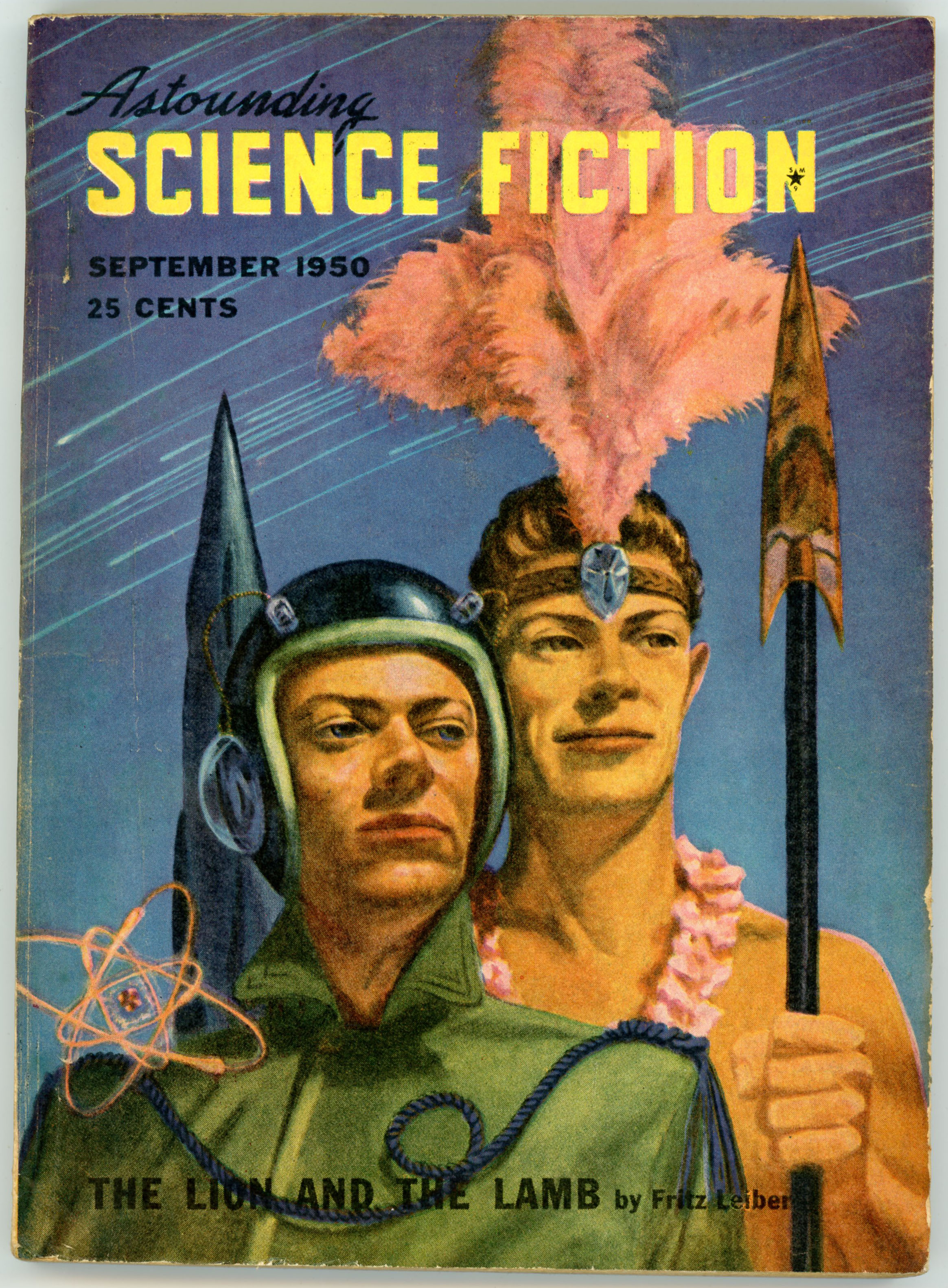

L. Sprague de Camp photo, from …

Gunn, James E., Alternate Worlds – The Illustrated History of Science Fiction, A&W Visual Library, Prentice-Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1975

Gandalf (both Grey and White), at …