Here’s Irving Howe’s 1972 New York Times review of Vasily Grossman’s Forever Flowing, with artist Daniel Maffia’s accompanying illustration.

Maffia’s art juxtaposes a portrait of Grossman with the image of a train, the latter symbolic of the book’s opening pages, which describe the journey of protagonist Ivan Grigoryevich (if he is actually a protagonist, for he seems far more having been acted upon than acting) back to Moscow after his release from decades of imprisonment in the Gulag.

While Grossman’s better known and far lengthier Life and Fate features characters fully “fleshed out” in terms of names and identities (personal history, life experiences, and relationships with family and friends) could the strikingly generic Russian name “Ivan Grigoryevich” – consisting solely of a given name and patronymic, thus lacking any connotation of nationality – have been an effort to create within one character a literary template for universal themes of freedom and justice?

Having read both novels, I find a comparison between them to be strikingly difficult because of dissimilarities in their length, literary structure, scope of action, and the disparity between the depth of character development in Life and Fate, versus the near one-dimensionality of characters in Forever Flowing. In addition, the books differ through Grossman’s focus within Life and Fate on the historical experience of the Jews of Russia (both civilian and military) within the context of the Second World War, against Forever Flowing’s universality, Jewish themes being apparent in only a single, searing, passage.

Yet, withall, I liked Forever Flowing more than Life and Fate, for despite the former’s lack of cohesion (Howe is entirely correct in his appraisal, “…he wrote out of so urgent a passion that he brushed aside the formal niceties of composition, these chapters have to be taken as set-pieces not well integrated with the plot.”) underlying themes are approached with a degree of directness and simplicity that is striking in effect and intensity.

Regardless and even because of their stylistic differences, both books are worthy of reading and contemplation.

________________________________________

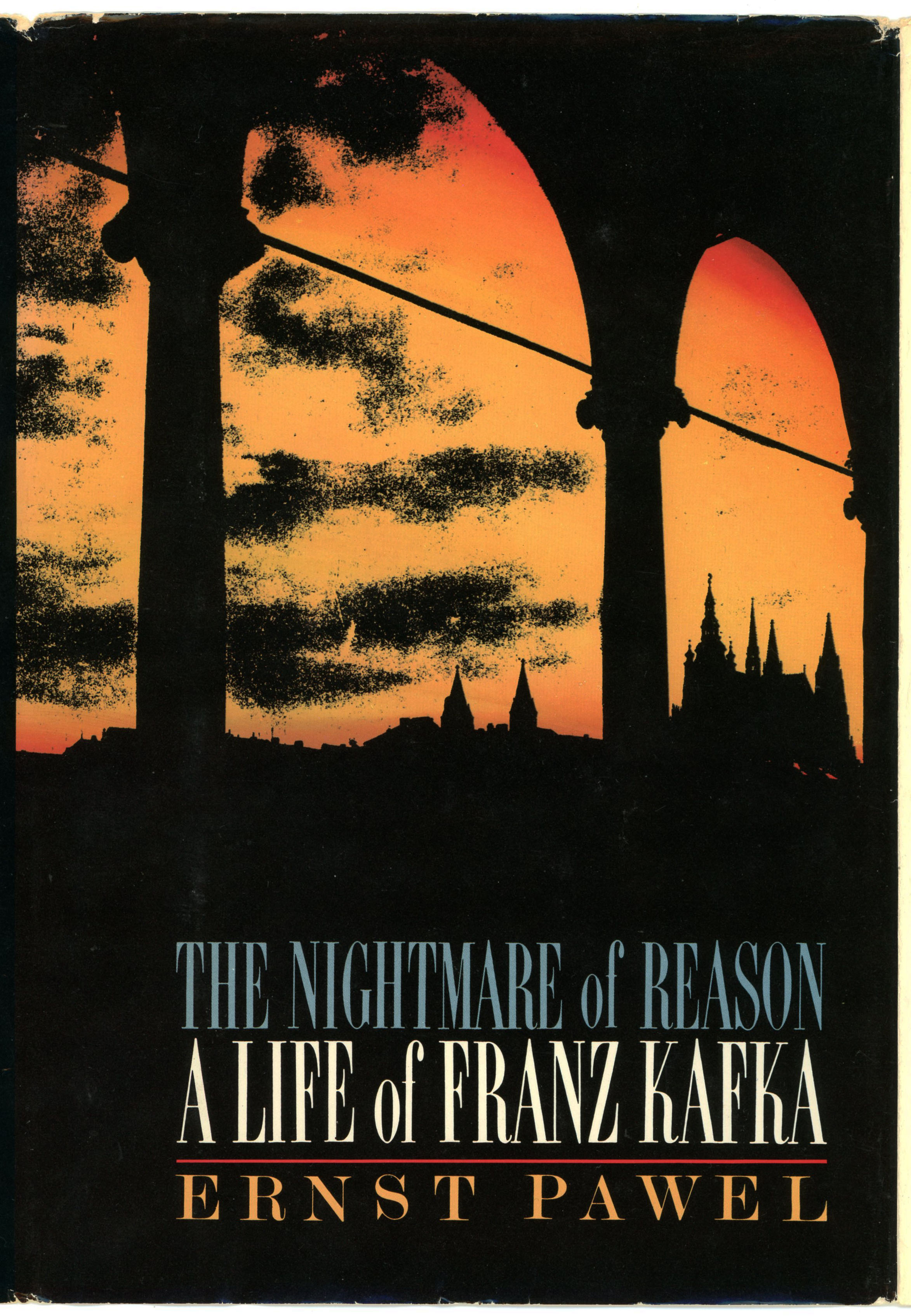

A bold underground novel of the split Russian soul

Forever Flowing

By Vasily Grossman.

Translated from the Russian by Thomas P. Whitney.

247 pp. New York: Harper & Row. $6.95.

By IRVING HOWE

The New York Times Book Review

March 26, 1972

For two centuries now, under czars and commissars, Russia has given us the most brutal autocracy and brilliant literature. During the last 20 years its best writing has come from poets, novelists and essayists who cannot publish in their own country but whose work, in defiance of the bureaucratic fist, finds its way into the West

For two centuries now, under czars and commissars, Russia has given us the most brutal autocracy and brilliant literature. During the last 20 years its best writing has come from poets, novelists and essayists who cannot publish in their own country but whose work, in defiance of the bureaucratic fist, finds its way into the West

Some of these writings, like Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s novel, “The First Circle,” Andrei Sinyavsky’s essay, “On Socialist Realism,” and Nadezhda Mandelstam’s memoir, “Hope Against Hope,” are masterpieces. Their strength comes not merely from a high order of individual talent, but from the unconditional attachment to freedom that is the animating idea of Russian underground literature (samizdat). Indeed, at a time when some Western intellectuals have again yielded themselves to authoritarian dogmas and charismatic dictators, it is these brave writers of the East – not only Russians but also Poles like Leszek Kolakowski and Yugoslavs like Milovan Djilas – who best uphold the values of independence, freedom, dissent.

Vasily Grossman’s “Forever Flowing,” written shortly before his death in 1964, is another of these remarkable books, known only to a few friends (and no doubt the secret police). It is a novel portraying the experiences and reflections of a man who returns to Moscow after 30 years in the Siberian labor camps; it contains pungent discussions of political ideas; and it trembles with the vision of freedom. At least in this book, Grossman is not so good a novelist as Solzhenitsyn or smooth an essayist as Sinyavsky. Yet in one major respect his book seems the boldest to emerge from the suppressed literature of Russia: It is the first, to my knowledge, that comes to grips with the myth of Lenin.

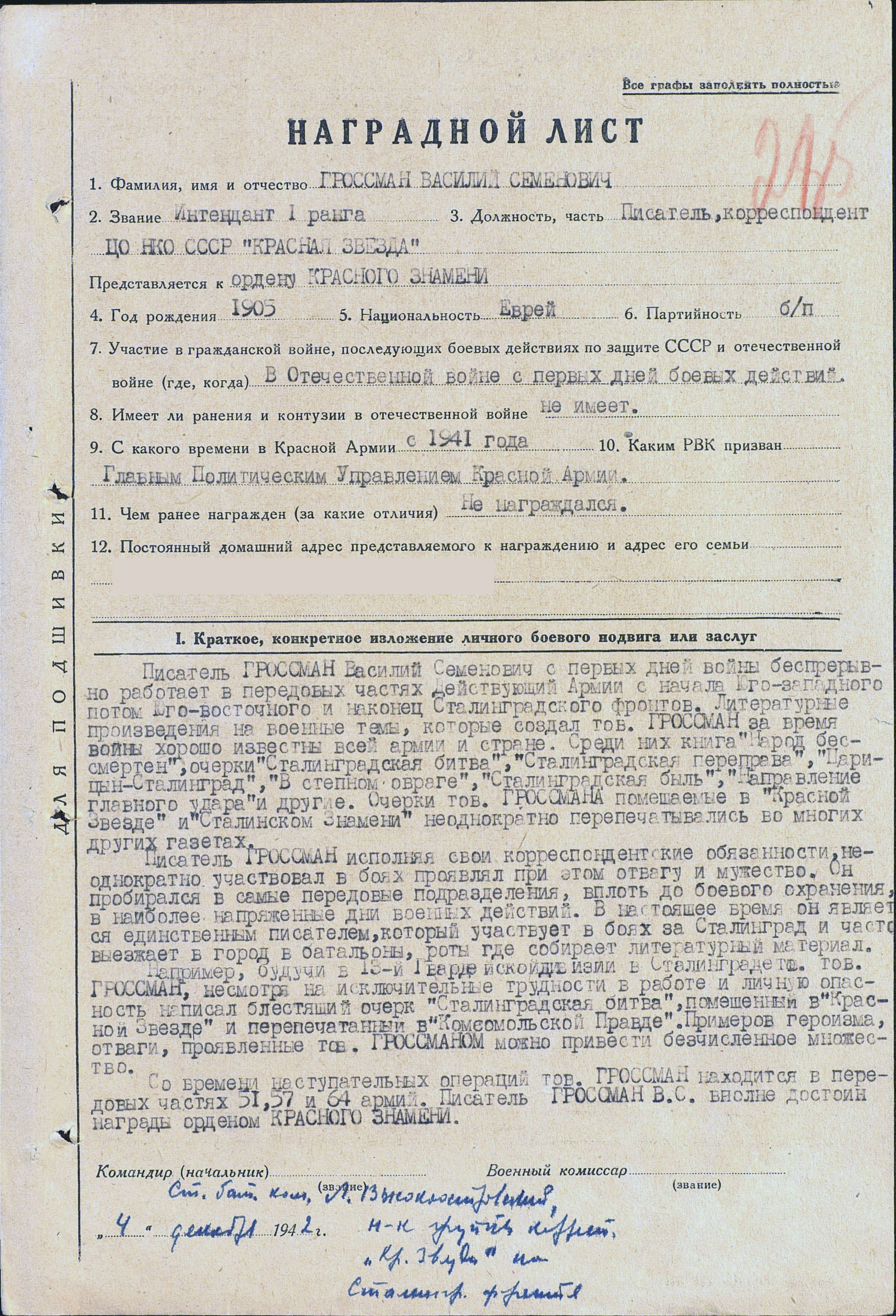

Grossman’s career holds remarkable interest, precisely because for so long a time it was quite ordinary. He began to publish in the 30s, when a novella of his attracted the favor of Maxim Gorky. Other writings established him as a gifted novelist who was especially admired by Russian literary people for his style. Apparently a decent man, he tried to maintain his integrity and nurture his talent during the Stalin years without paying too great a price in shame. Neither heroic nor slavish, he remained silent when he had to, but meanwhile kept his mind alive, storing up explosive ideas and impressions.

In 1946 he published a play, “If You Believe the Pythagoreans,” that was denounced by the party-line critics, and then, during the anti-Semitic campaign against “homeless cosmopolites.” he was attacked again Konstantin Paustovsky, the distinguished Russian writer, privately told a friend in the West that in these years Grossman wrote a novel which he, Paustovsky, considered a masterpiece but that the manuscript was confiscated by the secret police and no copies were allowed to remain. Nevertheless, Grossman kept writing “for the drawer,” completing “Forever Flowing,” not a masterpiece but a notable book, in his final years.

What seems most striking about his career is that, in ways not entirely clear from a distance, a man like Grossman could experience a major intellectual and moral transformation over a period of time – by himself? together with friends? – in which the received ideology of the Communist state was discarded and the scorned, “obsolete” values of liberalism or social democracy became a cherished possession. Reading the pages of “Forever Flowing” with their glow of humane reflectiveness, one wonders: How did people like Grossman hack their way out of the ideological jungle in which circumstances had trapped them? How, in their enforced isolation, did they find a path, and by no means uncritically, to the best of Western thought? Whatever the answers, one is almost tempted after reading this book to accept Grossman’s view – a view not exactly encouraged by recent history – that there is a natural, indestructible striving toward freedom inherent in human nature.”

“Forever Flowing” begins in a familiar manner: a worn old man is on a westward-moving train to Moscow. Mocked by the louts and officials who share his compartment, he keeps his silence. Ivan Grigoryevich is returning from the camps to which, half a life earlier, he had been sent because of an impulsive student speech deviating from Communist orthodoxy. The figure of the returned prisoner is a central one in recent Russian writing: the victim, the survivor, the man who remembers.

Ivan visits his cousin and boyhood chum, Nikolai, a small-talented scientist who has toadied a little over the years and now lives in “a world of parquet floors, glass-enclosed bookcases, paintings and chandeliers.” One man well-fed, smug, and uneasy; the other gaunt, tormented and irritable. Ivan makes no accusations. It is his very silence that provokes Nikolai into self-defense: “I went through trials and tribulations,” though “of course I did not ring out like Herzen’s bell.” It is hopeless, a dialogue of the deaf. What can a man from the camps say to a man with an apartment?

Beyond these acrid, sharply-contoured opening chapters, “Forever Flowing” has little plot. Ivan visits Leningrad, meets Pinegin, a former colleague, now a dignified gentleman with a fine coat. “Don’t worry,” bursts out Ivan in anticipation of a rebuff,”… like you, I, too, have a passport.” Pinegin replies with dignity: “When I run into an old friend, I am not in the habit of making inquiries about his passport” It sounds good, a word of solidarity at last. Later, we learn it was Pinegin who had denounced Ivan.

Ivan moves to a town in southern Russia, works as a laborer, meets a woman also worn out by suffering. She lived through Stalin’s campaign against the kulaks and the forced collectivization. They have a few moments together, not exactly of happiness, but of the peace that comes when people can at last speak with honesty. The woman dies. Ivan is again alone, with his thoughts and questions, “gray, bent and changeless.”

Woven through this simple story are linked segments of incident and passages of reflection. Two scenes are especially strong. One is an imaginary trial, perhaps running through Ivan’s mind, in which the informers who had sent millions to the camps are now arraigned. Each speaks freely, from his own motives, for his own skin. Especially forceful is “the well-educated informer”:

“Why are you determined to expose particularly those like us who are weak? Begin with the state. Try it! After all, our sin is its sin. Pass judgment on it! Fearlessly, out in the open. … And then explain one other thing, if you please. Why have you waited till now? You knew us all in Stalin’s lifetime. You used to greet us cordially then and waited to be received at the doors of our offices.”

The other scene, rich with Dostoevskian echoes, consists of Ivan’s recollections of a critical moment in prison. Next to him lay “the most intelligent of all the men I ran into. But his mind was frightening. Not because it was evil [but because] he refused to accept my faith in freedom.” This fellow-prisoner believed “in the law of the conservation of violence.” The history of life, he insisted, “is the history of violence triumphant. It is eternal and indestructible.” To Ivan the pain of these words seemed greater than the pain of the interrogator’s blows a few hours earlier. “They dragged me off again to interrogation … I felt relieved. I believed again in the inevitability of freedom.”

The chapters of intellectual reflection are meant no doubt to be taken as the thoughts of Ivan. But perhaps because Vasily Grossman could not properly finish his book or perhaps because he wrote out of so urgent a passion that he brushed aside the formal niceties of composition, these chapters have to be taken as set-pieces not well integrated with the plot. No matter; they are striking in their own right.

Grossman is fascinated by the paradox that runs through the whole Russian revolutionary movement How can it be that in the same people there exists a “meekness and readiness to endure suffering … unequaled since the epoch of the first Christians” together with “contempt for and disregard of human suffering, subservience to abstract theories, the determination to annihilate not merely enemies but those comrades who deviated even slightly front complete acceptance of the particular abstraction …”? Grossman finds his answer in the tradition of Russian messianism, a “sectarian determinism, the readiness to suppress today’s living freedom for the sake of an imaginary freedom tomorrow.”

In a powerful sketch of Lenin, he connects the revolutionary leader with this two-sided tradition: the gentle selfless man who loved music and showed tenderness toward friends, and the harsh politician who, in rage against heresies, laid the basis for the party-state dictatorship. This kind of revolutionary Grossman sees as a man who fancies himself a surgeon of history: “His soul is really in his knife.” Grossman’s Stalin reduced Leninism to its political essentials.

But Grossman does not stop there. Through a confrontation with those notions of a unique Russian destiny that course through the work of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky as well as, less assertively, Solzhenitsyn, he performs a first-rate intellectual service. The great Russian writers, both the reactionaries and some revolutionaries, professed to find unique qualities in the Russian soul which they regarded as the last unsullied vessel of Christian purity; they sneered, too often and with disastrous results, at the liberalism of the West. All these prophets “failed to see that the particular qualities of the Russian soul did not derive from freedom, and that the Russian soul had been a slave for a thousand years.” And then a crucial passage:

“In the Russian fascination with Byzantine, ascetic purity, with Christian meekness, lives the unwitting admission of the permanence of Russian slavery. The sources of this Christian meekness, and gentleness, of this Byzantine, ascetic purity, are the same as those of Leninist passion, fanaticism, and intolerance.”

This is the voice of a “Westerner,” the kind of Russian intellectual who, alas, never has had enough influence in his own country. But now, after the ordeal of the past half-century, what Grossman wrote in the privacy of his study, perhaps without expecting that it would ever be published, takes on the strength of a central truth. It is, I think, the one supremely revolutionary idea: that without democratic freedoms no society, whether it calls itself capitalist or socialist, whether it has an industrialized or backward economy, can be tolerable

It is also the one permanently revolutionary idea, for no one can say with assurance that it will survive our century and every thoughtful man knows that it will always have a precarious life, its triumph never assured.

Suggested Readings

Aciman, Alexander, Book Review: Vasily Grossman, the Great Forgotten Soviet Jewish Literary Genius of Exile and Betrayal, Lives Inside Us All, Tablet, October 23, 2017

Capshaw, Ron, The Scroll: The Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee Was Created to Document the Crimes of Nazism Before They Were Murdered by Communists – For the crime of acknowledging Jewish identity, the committee’s members were killed in a Stalinist pogrom, Tablet, November 29, 2018

Epstein, Joseph, The Achievement of Vasily Grossman – Was he the greatest writer of the past century?, Commentary, May, 2019.

Eskin, Blake, Book Review: Eyewitness – A collection of Vasily Grossman’s shorter work offers a chance to reassess the Soviet master’s life and legacy. A conversation with Grossman translator Robert Chandler, Tablet, December 8, 2010

Kirsch, Adam, Book Review: No Exit: Life and Fate, Vasily Grossman’s indispensable account of the horrors of Stalinism and the Holocaust, puts Jewishness at the heart of the 20th century, Tablet, November 30, 2011

Vapnyar, Lara, Book Review: Dispatches – How World War II turned a Soviet loyalist into a dissident novelist. Plus: An audio interview with the editor of A Writer at War, Tablet, January 30, 2006

Taubman, William, Book Review: Life and Fate: A biography of Vasiliy Grossman, the Soviet writer whose masterpiece compared Stalin’s regime to Hitler’s, The New York Times Book Review, p. 16, July 14, 2019

________________________________________

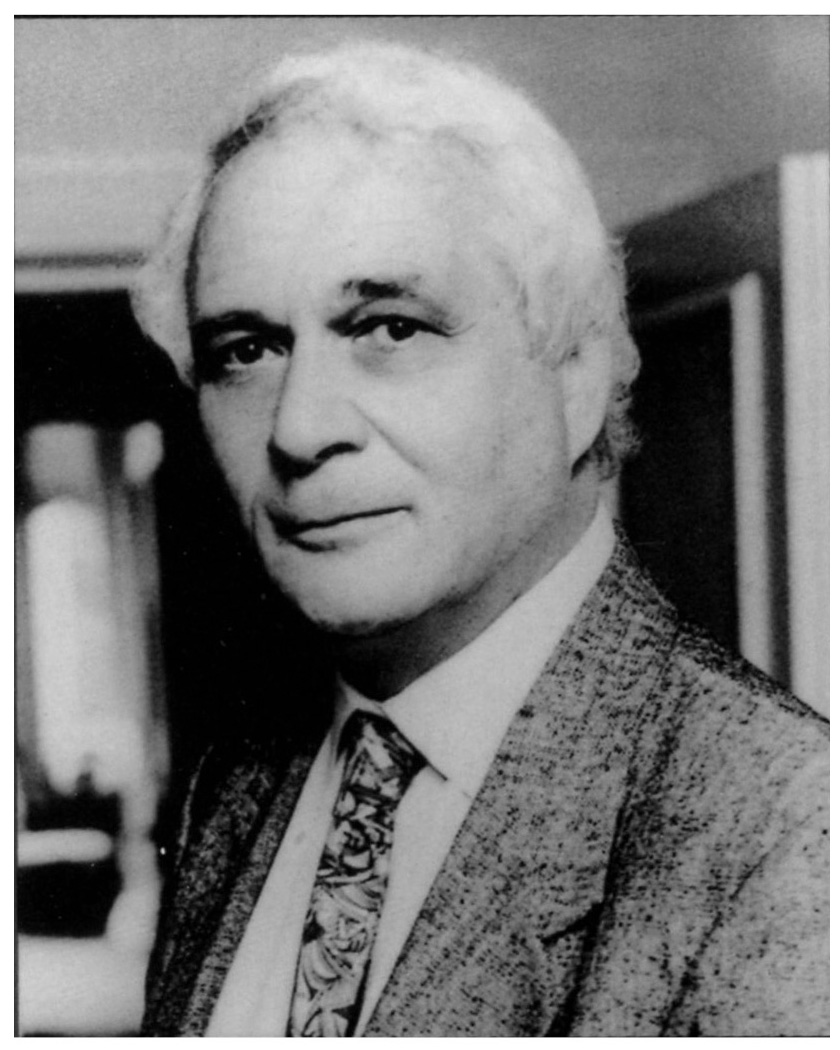

________________________________________ (Photograph accompanying Zelda Gamson’s essay of May 23, 2015 “The Life and Fate of Vasily Grossman“, at Jewish Currents.)

(Photograph accompanying Zelda Gamson’s essay of May 23, 2015 “The Life and Fate of Vasily Grossman“, at Jewish Currents.)