At the core of all literary genres are stories that are emblematic – in terms of theme, plot, characters, and setting. Tales of adventure, drama, fantasy, mystery, romance, tragedy, and more, are represented by particular works, which in the names of their very titles, represent to the reader (or, viewer!) “that” body of literature, without even the briefest need for depiction, description, or explanation.

In the genre of science fiction, one such tale (well, really, a set of tales) continues to remain iconic: Isaac Asimov’s Foundation Trilogy, comprising Foundation, Foundation and Empire, Second Foundation (the trilogy having been expanded with two sequels and two prequels commencing in 1981), which initially appeared as a series of eleven short stories in Astounding Science Fiction from May of 1942, through January of 1950.

As derived from information at the International Science Fiction Database, the Wikipedia entry for the Foundation Series, plus a brief perusal of my own copies of Astounding, the body of stories that comprise the Trilogy are listed below:

May, 1942 – “Foundation” (also known as “The Encyclopedia”)

June, 1942 – “Bridle and Saddle”

August, 1944 – “The Big and The Little” (also known as “The Merchant Princes”)

October, 1944 – “The Wedge” (also known as “The Traders”)

April, 1945 – “Dead Hand”

November, 1945, December, 1945 – “The Mule”

January, 1948 – “Now You See It”

November, 1949, December 1949, January 1950 – “And Now You Don’t” (also known as “Search for The Foundation”)

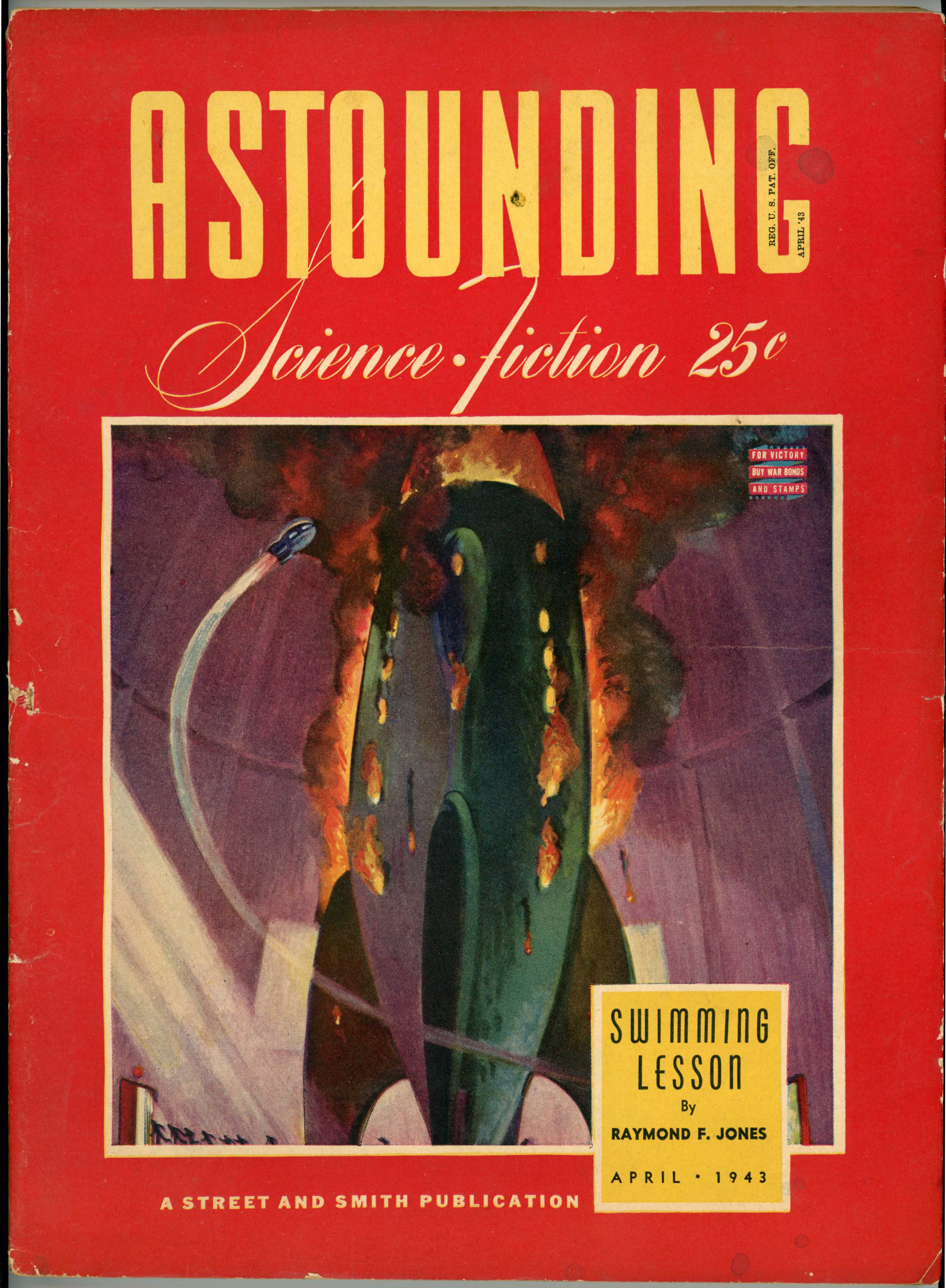

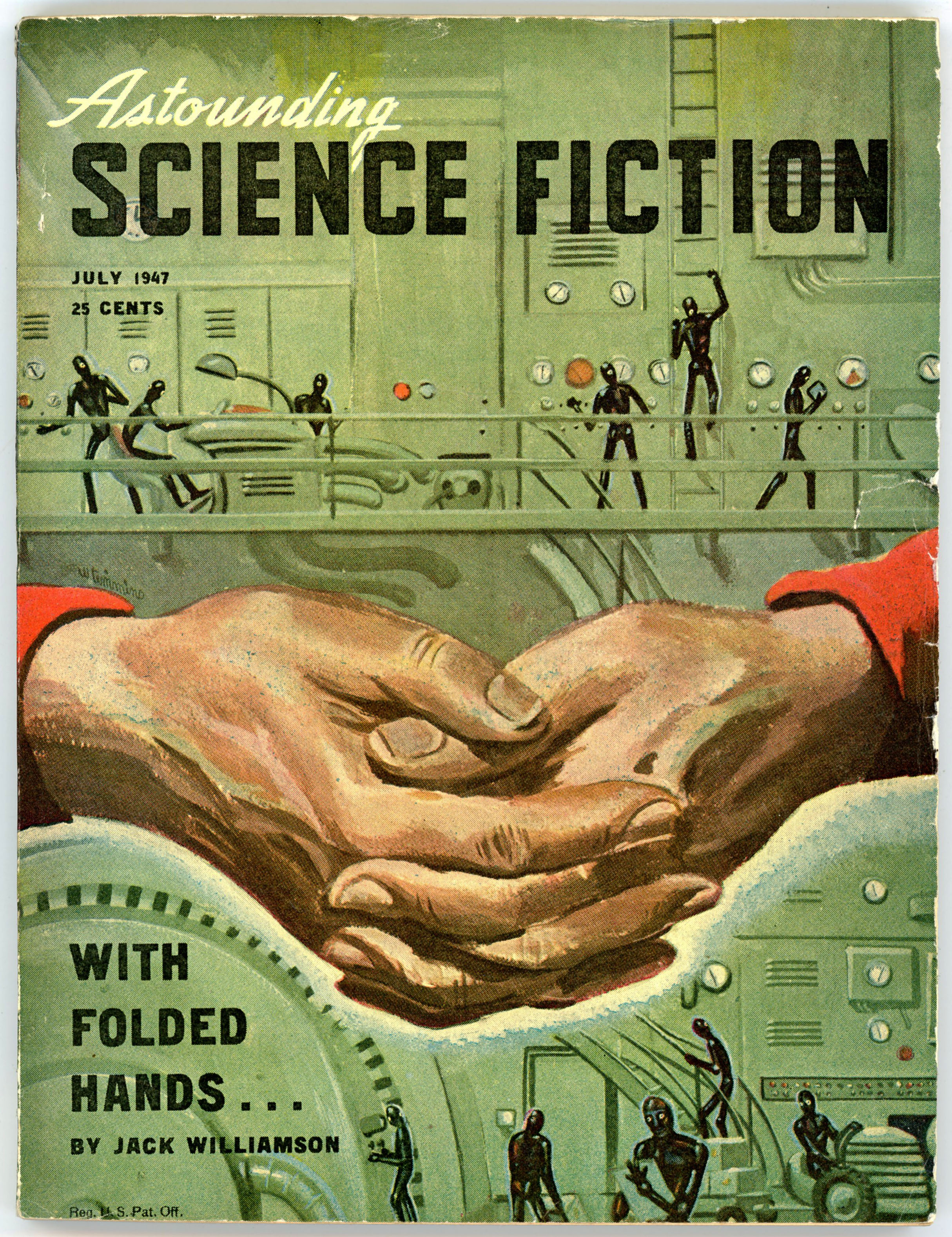

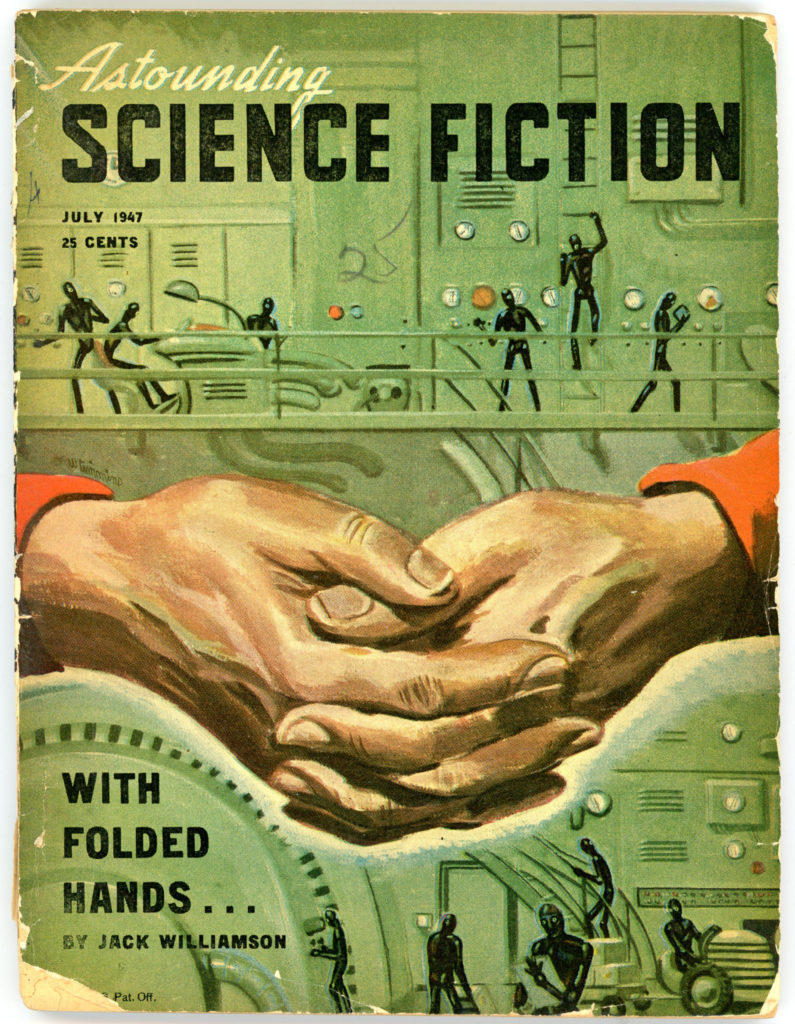

Of the eleven issues of Astounding listed above, six were published with cover art symbolizing or representing the actual Foundation story within the particular issue. But, the cover art for issues of May, 1942; October, 1944; December, 1945; December, 1949, and January, 1950 was unrelated to Asimov’s story.

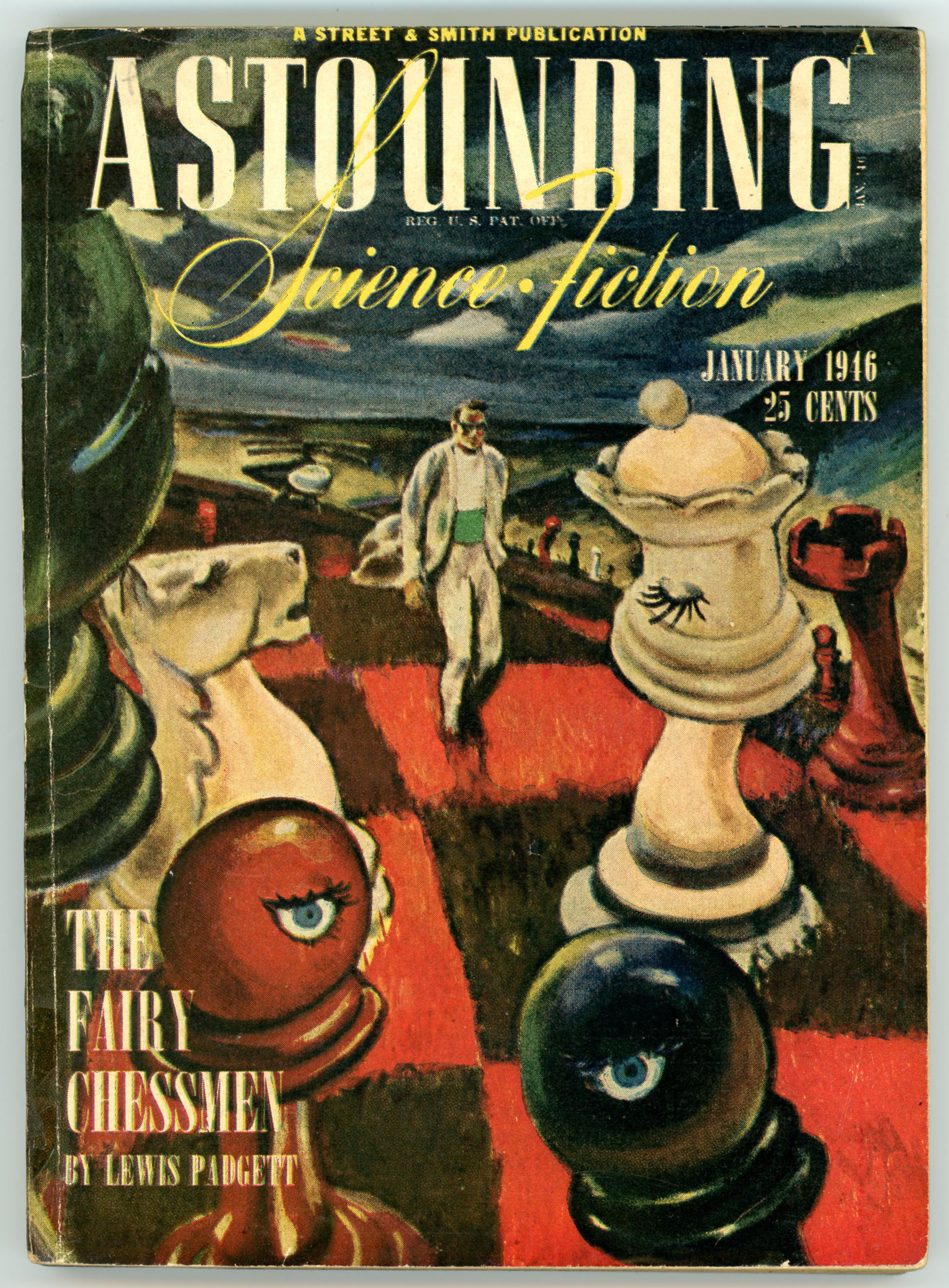

An example appears below. It’s the cover of Astounding for December, 1945, with art by William Timmins for Lewis Padgett’s (Henry Kuttner and Catherine L. Moore’s) “Beggars in Velvet”. While I’ve not yet read the story, the juxtaposition of archers garbed in “Daniel Boonish” attire in the left foreground, with a crowd of seeming civilian hostages to the right – with a futuristic cityscape behind – presents an unusual sight.

Within appears part two of “The Mule”, the text of both parts of which was later incorporated into “Foundation and Empire”.

______________________________

______________________________

The story is illustrated with five drawings by Paul Orban, two of which – the most “science-fictiony” – you can view below.

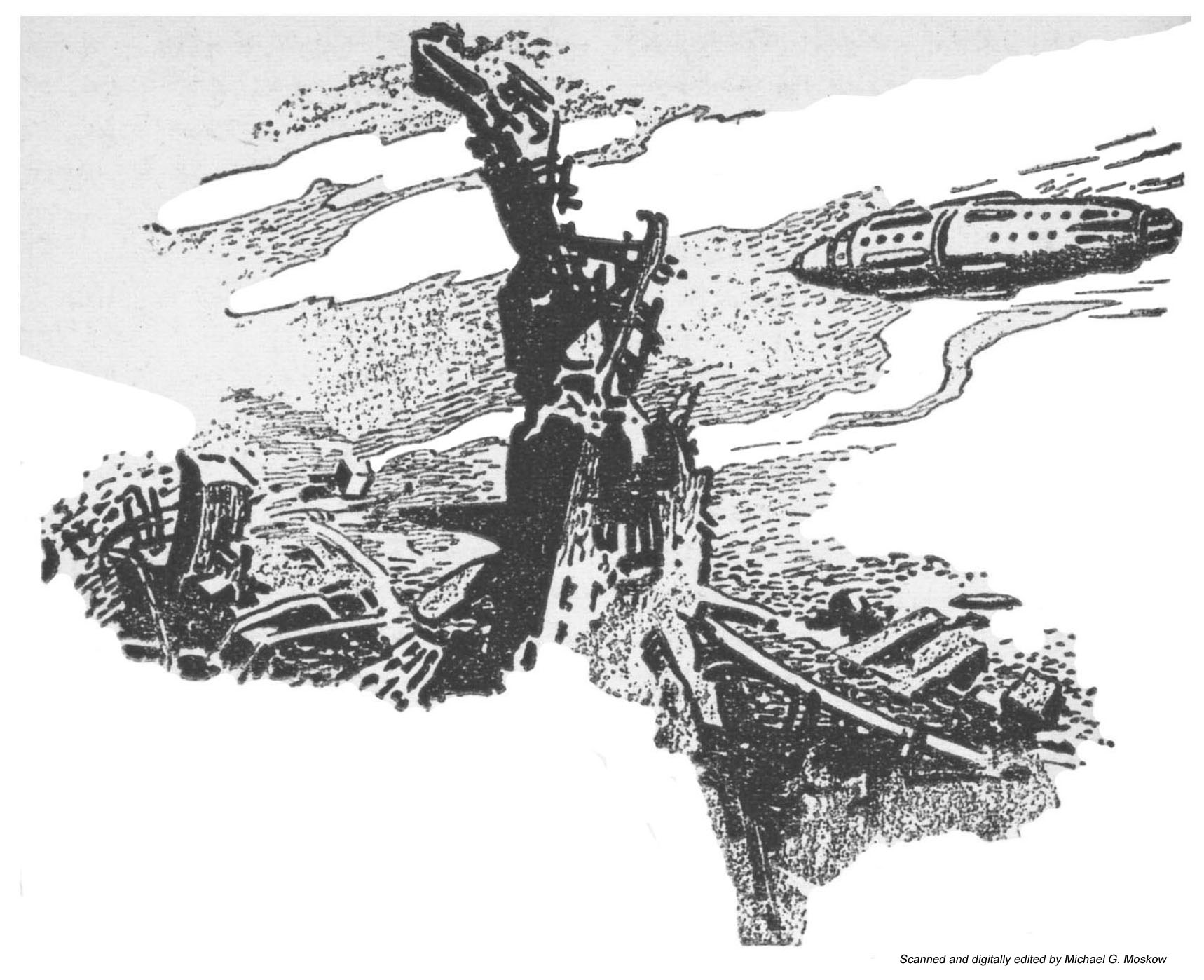

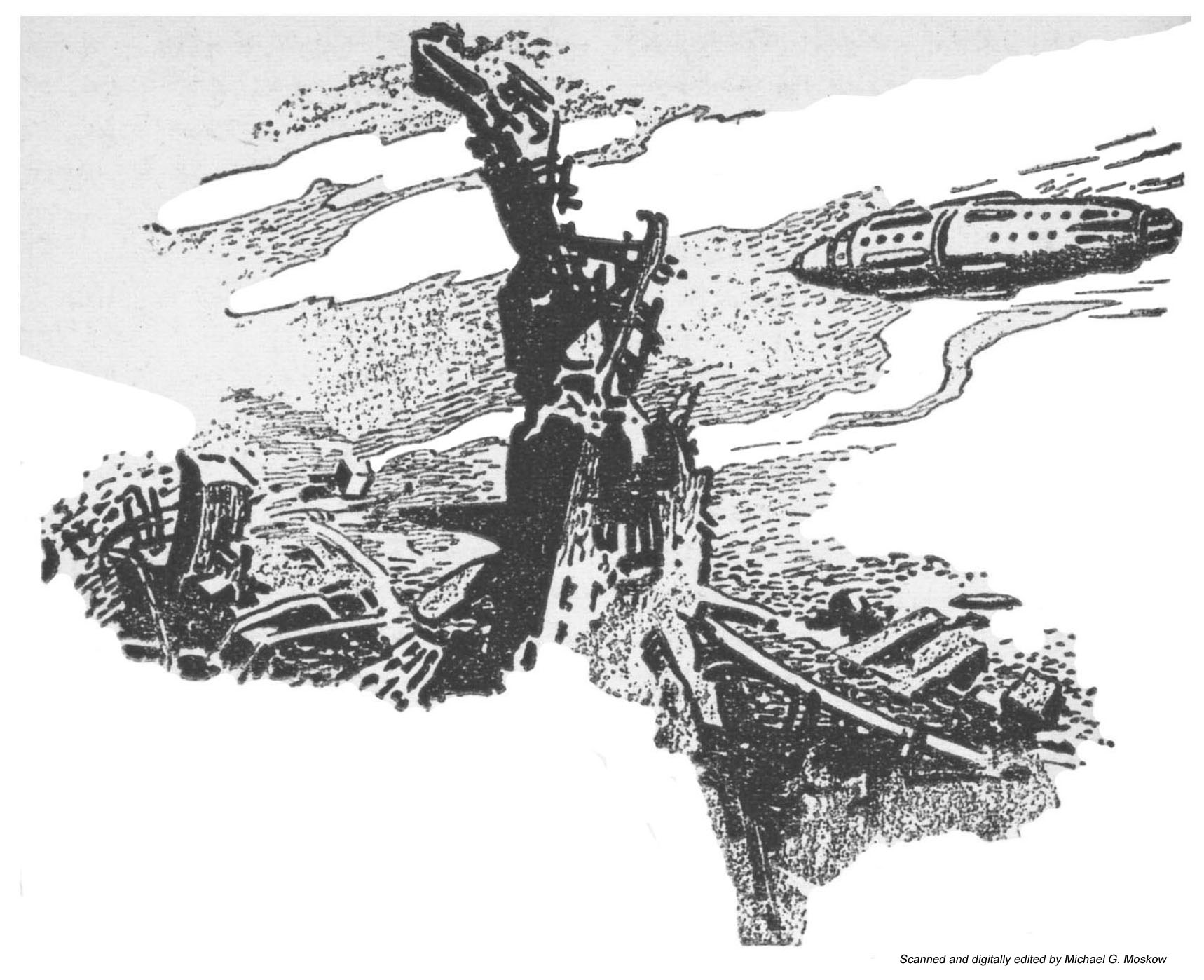

This image – the leading illustration of the story – shows the spacecraft Bayta, crewed by Toran and Bayta Darell, Ebling Mis, and Magnifico (the Mule himself, unbeknownst to the other three) as they search for the Great Library of Trantor. The year: 12,376, by Galactic Era chronology.

(Illustration on page 60)

(Illustration on page 60)

“The location of an objective area the great world of Trantor presents a problem unique in the Galaxy. There are no continents of oceans to locate from a thousand miles distance. There are no rivers, lakes, and islands to catch sight of through the cloud rifts.

The metal-covered world was – had been – one colossal city, and only the old Imperial palace could be identified readily from outer space by a stranger. The Bayta circled the world at almost air-car height in repeated painful search.

From polar regions, where the icy coating of the metal spires were somber evidence of the weather-conditioning machinery, they worked southwards. Occasionally they could experiment with the correlations – (or presumable correlations) – between what they saw and what the inadequate map obtained at Neotrantor showed.

But it was unmistakable when it came. The gap in the metal coat of the planet was fifty miles. The unusual greenery spread over hundreds of square miles, inclosing the mighty grace of the ancient Imperial residences.

The Bayta hovered and slowly oriented itself. There were only the huge super-causeways to guide them. Long straight arrows on the map; smooth, gleaming ribbons there below them.

What the map indicated to be the University area was reached by dead reckoning, and upon the flat area of what once must have been a busy landing-field, the ship lowered itself.

It was only as they submerged into the welter of metal that the smooth beauty apparent from the air dissolved into the broken, twisted near-wreckage that had been left in the wake of the Sack. Spires were truncated, smooth walls gouted and twisted, and just for an instant there was the glimpse of a shaven area of earth – perhaps several hundred acres in extent – dark and plowed.” (pp. 93-94)

______________________________

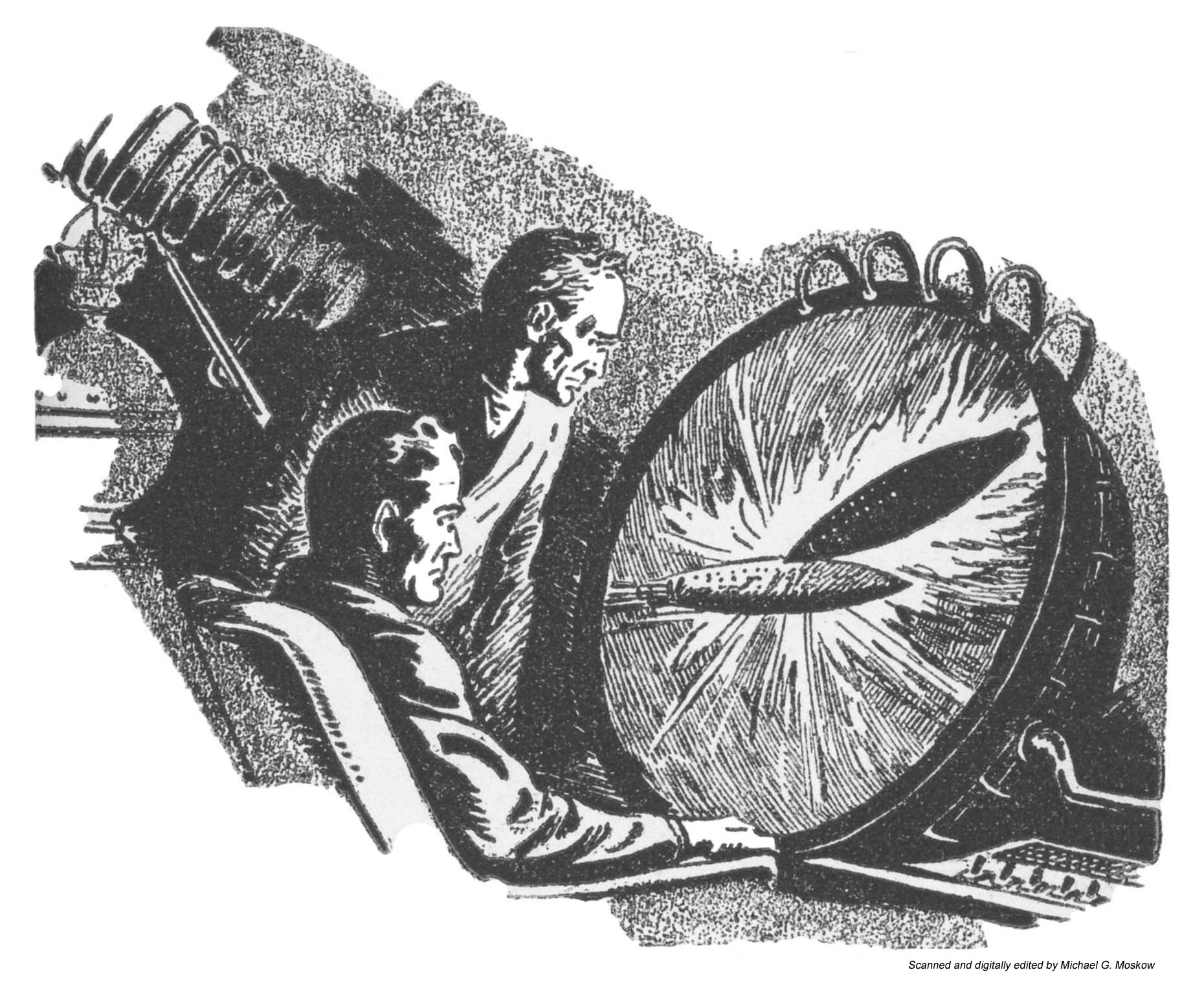

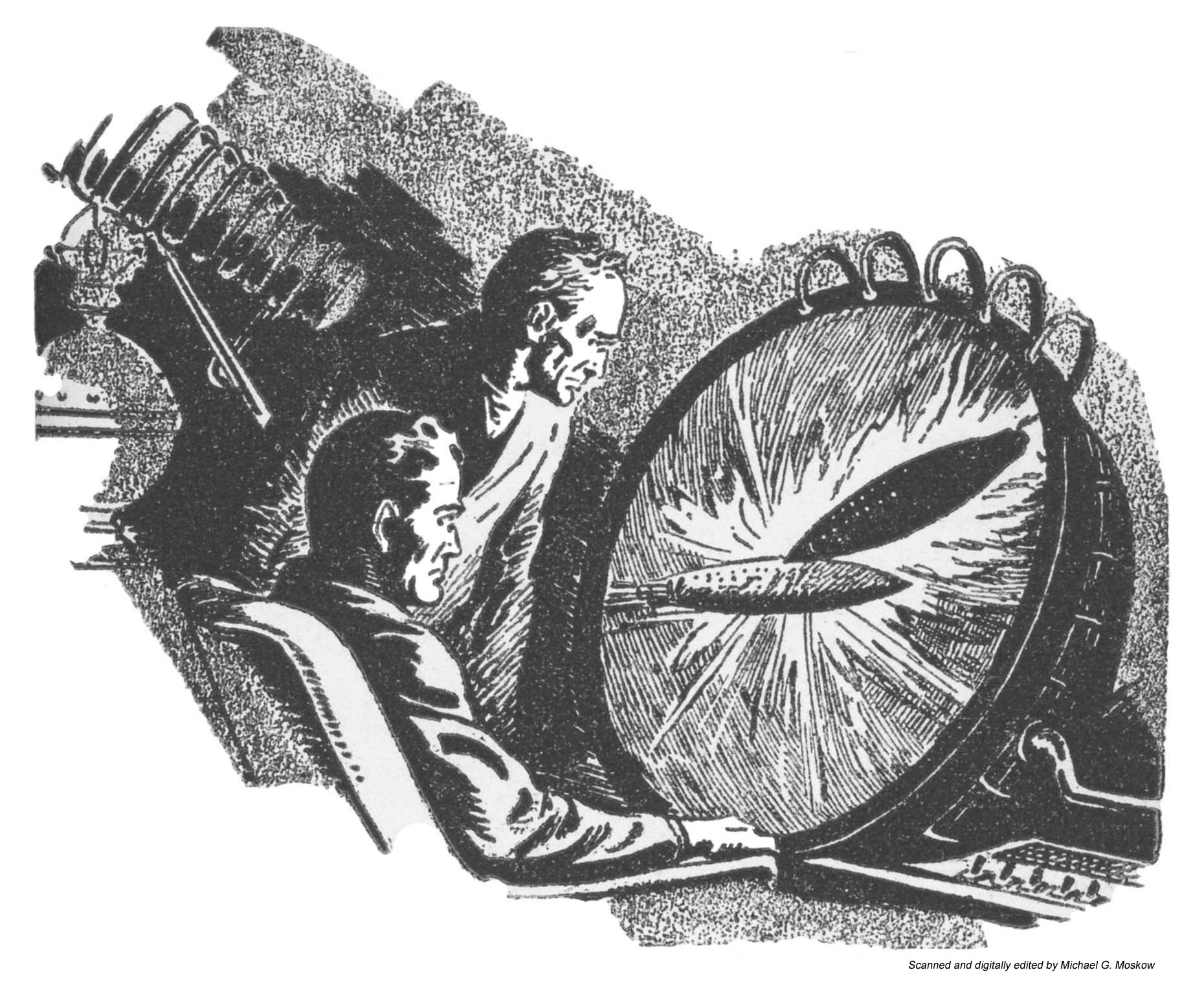

This image shows an Empire spacecraft ramming the Foundation spaceship Cluster, during a battle between space fleets of the Foundation and the Empire. The events are watched live (evidently, the time-lag inherent to speed-of-light communication over intragalactic distances is not an issue – oh, well!) by Toran Darell and Ebling Mis.

(Illustration on page 151)

(Illustration on page 151)

“Toran sat down upon the cot that served as Magnifico’s bed, and waited. The propaganda routine of the Mule’s “special bulletins” were monotonously similar. First the martial music, and then the buttery slickness of the announcer. The minor news items would come, following one another in patient lock step. Then the pause. Then the trumpets and the rising excitement and climax.

Toran endured it. Mis muttered to himself.

The newscaster spilled out, in conventional war-correspondent phraseology, the unctuous words then translated into sound the molten metal and blasted flesh of a battle in space.

“Rapid cruiser squadrons under Lieutenant General Sammin hit back hard at the task force striking out from Iss – ” The carefully expressionless face of the speaker upon the screen faded into the blackness of a space cut through by the quick swaths of ships reeling across the emptiness in deadly battle. The voice continued through the soundless thunder –

“The most striking action of the battle was the subsidiary combat of the heavy cruiser Cluster against three enemy ships of the ‘Nova’ class – ”

The screen’s view veered and closed in. A great ship sparked and one of the frantic attackers glowed angrily, twisted out of focus, swung back and rammed. The Cluster bowed wildly and survived the glancing blow that drove the attacker off in twisting reflection.

The newsman’s smooth unimpassioned delivery continued to the last blow and the last hulk.

Then a pause, and a largely similar voice-and-picture of the fight off Mnemom, to which the novelty was added of a lengthy description of a hit-and-run landing – the picture of a blasted city – huddled and weary prisoners – and off again.” (pp. 77-78)

_____________________

When I first saw Orban’s drawing of the viewing screen (on page 151), I was intrigued: A large-diameter viewing scope, with a set of cables attached to its periphery, mounted at an angle to a seated viewer’s line of sight? Hmmm…

Where did I see such image – or its inspiration – before?

Then, I remembered.

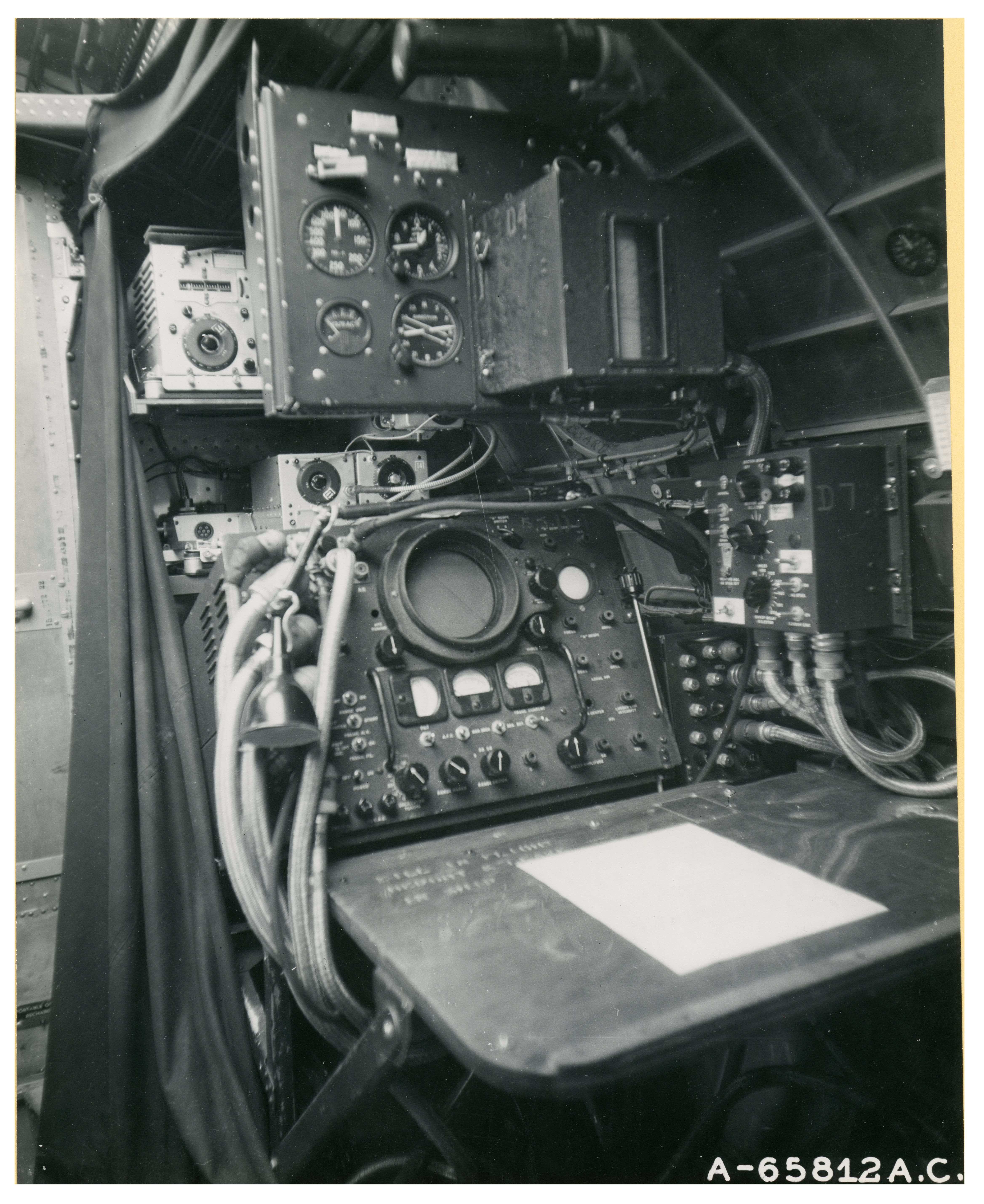

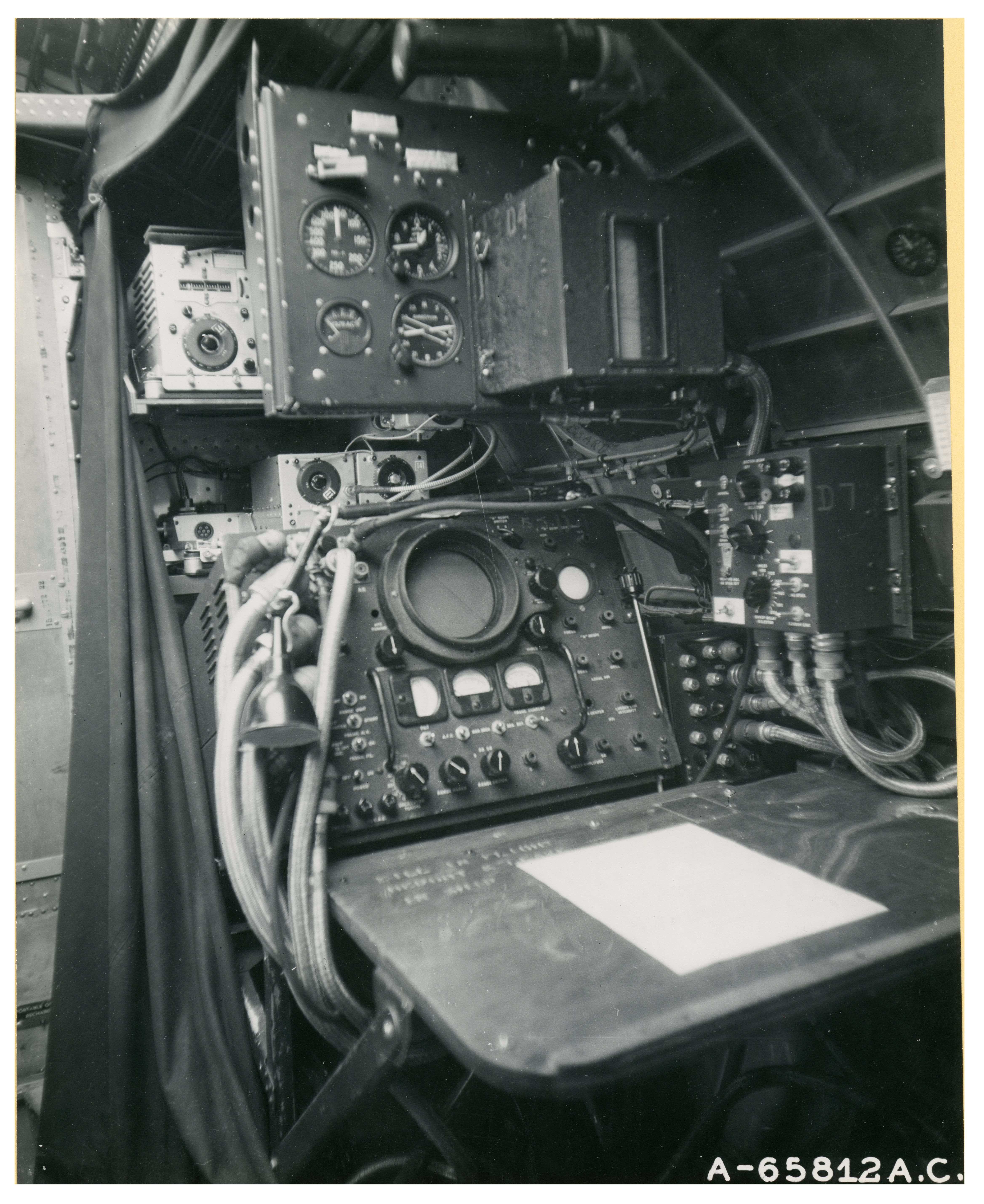

The design of Orban’s view-screen – or, at least the front of it – bears a similarity to cathode-ray tube of the World War Two era H2X ground-mapping radar unit, which was primarily utilized in heavy bombers (B-17 Flying Fortresses and B-24 Liberators) of the United States Army Air Force.

Photographs of H2X units in two B-17 Flying Fortress bombers of the 401st Bomb Group of the British-based Eighth Air Force – taken in England on December 5, 1944 – were received in June of 1945, and presumably released to the news media after that date, months before the publication of Orban’s illustrations in the December issue of Astounding.

Given the timing of the photographs’ distribution, and their presumed availability to the general public, could Paul Orban have been inspiration for his illustration in Astounding have been these photographs?

I don’t really know. Just pure speculation.

But, it’s an idea.

You can view the two images of the H2X radar unit below. They’re among the nearly 89,000 images in NARA’s Records Group 342 (Black and White and Color Photographs of U.S. Air Force and Predecessor Agencies Activities, Facilities, and Personnel – World War II ) now available to the public through Fold3.com. Since I scanned both pictures at 400 dpi, a “full-screen” / enlarged view will reveal detailed views of the units’ buttons, switches, control panels and associated equipment.

Army Air Force Photo 65812AC / A12719

Army Air Force Photo 65812AC / A12719

Based on this set’s location relative to the bulkhead and fuselage, this unit is probably located in the navigator’s station of the B-17.

______________________________

Army Air Force Photo A-65812AC / A12720

Army Air Force Photo A-65812AC / A12720

Based on the location of the door (to the left) and curvature of the fuselage wall (on the right), this unit is situated within the B-17’s radio compartment. Note the curtain on the left and above the H2X unit, giving the radar operator a view of his scope unimpeded by sunlight.

References

Foundation Series – at Wikipedia

Foundation and Empire – at Wikipedia

Isaac Asimov Short Stories Bibliography – at Wikipedia

International Science Fiction Database – Foundation (Original Stories)

World War Two German Technical Analysis of Captured R-78 / APS-15A Radar (featuring Photo A-68512AC) – at Foundation for German Communication and Related Technologies

R-78A Receiver-Indicator, AN/APS-15 Radar Equipment – Two color images from Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum