This cartoon, by The New Yorker cartoonist George Price, is hilarious, for it takes a commonplace idea – a literary idea – and carries it to an (il)logical conclusion. More than the merely weird idea of assembling all the authors of a anthology’s collected works for a single book signing, the appearance, facial expression, and attire of every individual is unique, exaggeratingly embodying the life experience of every author. It’s this, combined with the hilarity of a collective book signing, makes the cartoon work so well.

____________________

____________________

Price’s cartoon reminds me of the cover of the October, 1952 issue of Galaxy Science Fiction, which featured depictions of twenty contributors (excluding “Bug-Eye”) who were making the by then two-year-old magazine a success. A very clever idea. The magazine leads with a report to its readers touching upon its successes, challenges, and plans for the future, and mentions upcoming works by Isaac Asimov and Clifford Simak, and, includes a key – reproduced below – identifying the authors and contributors shown on the cover.

____________________

Annual Report to our Readers

The twelvemonth between our first annual report and this, which marks the beginning of our third year, was rammed full of activity for GALAXY. It all boils down to this one astonishing fact, however:

GALAXY has acquired the second largest circulation in science- fiction and is pushing hard toward first place.

For a magazine to achieve this record in so short a time is a tribute to its unyielding policy of presenting the highest quality obtainable; to its readers for their loyalty and appreciation; to its authors for helping it maintain those standards and even advance them.

During the turbulent first year of GALAXY’s existence, other publishers thought the idea of offering mature science fiction in attractive, adult format was downright funny. They knew what sold – shapely female endomorphs with bronze bras, embattled male mesomorphs clad in muscle, and frightful alien monsters in search of a human meal.

Even our former publisher [World Editions, Inc., 105 West 40th St., New York, N.Y. – not this contemporary World Editions!] became infected with that attitude, and the resulting internal conflicts were no joke at all. But now:

• We have the biggest promotion campaign mapped out that any science fiction magazine has ever had.

• We are working out the broadest circulation possible. Note that we reach the stands regularly on the second Friday of each month. (Subscribers, however, get their copies at least five to ten days before.)

• Better printing, paper and reproduction of art lie ahead.

• These new art techniques I mentioned in the past are on their way. They were stubborn things to conquer, but you’ll be seeing them soon.

• If you want to find WILLY LEY in a science fiction magazine henceforth, you’ll have to buy GALAXY. As our science editor, he will work exclusively for us in this field.

• Last and by far the most important, the literary quality of GALAXY will continue to be a rising curve – as steeply rising as we can manage.

Coming up, for example:

• November: THE MARTIAN WAY by Isaac Asimov, a novella, that introduces problems and situations in space travel that I have never seen before,.

• December: RING AROUND THE SUN by Clifford D. Simak is a powerful new serial with a startling theme and one surprising development after another.

• March: After the conclusion of the Simak serial, we have THE OLD DIE RICH by a chap named Gold. Naturally, the story was read by impartial critics – no writer can judge his own work – and they report it’s GALAXY quality. I hope you’ll agree with them.

Yes, it’s been a fine year. Next year looks even better.

– H.L. GOLD

____________________

1 – Fritz Leiber (“Gonna’ Roll the Bones”)

2 – Evelyn Paige

3 – Robert A. Heinlein

4 – Katherine MacLean (Dragons and such)

5 – Chesley Bonestell

6 – Theodore Sturgeon

7 – Damon Knight (“To Serve Man”)

8 – H.L. (Horace L.) Gold

9 – Robert Guinn

10 – Joan De Mario

11 – Charles J. Robot

12 – Cyril Kornbluth

13 – E.A. (Edmund A.) Emshwiller

14 – Willy Ley

15 – F.L. Wallace

16 – Isaac Asimov

17 – Jerry Edelberg

18 – Groff Conklin (anthologist)

19 – John Anderson

20 – Ray Bradbury (“The Fireman” (“Fahrenheit 451”))

21 – Bug Eye

____________________

____________________

But, where did Horace Gold get the very idea to acknowledge people instrumental to Galaxy’s success, in such a clever way?

I don’t know.

But, while perusing the contents of other, lesser known magazines at the Luminist Archive, I came across the November, 1951 issue of Marvel Science Fiction, which features cover art by Hannes Bok, in his own immediately recognizable style…

____________________

…and this two-page cartoon of the members of the by then four-year-old “Hydra Club”, an organization of professionals in the field of science fiction. Though far more “busy” than the scene depicted on the cover of Galaxy, the design is remarkably similar, right down to the number key at the bottom of the cartoon, and, the accompanying diagram of “who’s who” at lower right, the names of “who” are all listed below.

Was this the inspiration for Horace Gold, or, art director W.I. Van Der Poel? Given the timing, could be!

THE HYDRA CLUB

Text by Judith Merril

(Illustration by Harry Harrison)

An organization of Professional Science Fiction Writers, Artists and Editors.

Article One: The name of this organization shall be the Hydra Club.

Article Two: The purpose of this organization shall be…

PUZZLED silence greeted the reader as he lay down the proposed draft of a constitution, and looked hopefully at the eight other people in the room.

“The rest of it was easy,” he explained, “but we spent a whole evening trying to think of something for that.”

“Strike out the paragraph,” someone said. “We just haven’t got a purpose.”

And so we did. The Hydra Club was, officially, and with no malice in the forethought, formed as an organization with no function at all. It was to meet twice a month; it hoped to acquire a regular meeting place and a library of science fiction; its membership was to be selected on no other basis than the liking and approval of the charter members, who organized themselves into a Permanent Membership Committee for the new club.

That was in September, 1947. In four years of existence, the club has increased sevenfold. Its roster now lists more than sixty members, and the number is that low only because of the strict stipulation that admission to membership is by invitation only. There is no way for a would-be member to apply for admission; and invitations are issued only after the holding a complex secret-ballot blackball vote.

Of the nine charter members of the club, five are still active on the Permanent Membership Committee. Lester del Rey, who had been absent from the science fiction field entirely for several years, when the club was started, is now once again a leading name in the field. Dave Kyle and Marty Greenberg, who first met each other in the organizational days of the club, have since become partners in a publishing firm, Prime Press. Fred Pohl, who was then still writing an occasional story under the pen-name of James MacCreigh, has developed the then still-struggling Dirk Wylie agency into the foremost literary agency in the science fiction field. And yr. humble correspondent, who had just a few months earlier written her first science fiction story, has since become, among other things, Mrs. Frederik Pohl.

There are half a hundred other names on the rolls, many of which would be completely unfamiliar to science fiction fandom. The Club has never attempted to limit its membership to professionals working in the field. It has endeavored only to gather together as many congenial persons as possible. In the four years of its existence there have been many changes in character, constitution, solvency, and situation. A considerable library has been acquired by gift and donation, but no permanent meeting place or library space has ever been found. Meetings are now held only once a month, sometimes in the studio apartment of the Pratts’, or that of Basil Davenport, more often in a rented hall. From time to time, under the impetus of an unwonted ambition, the club has even initiated major endeavors, and less frequently has actually carried them through.

The single exception to this renewed enthusiasm for purposelessness is the annual Christmas party … perhaps because we have found it possible for all concerned to have a remarkably good time at these affairs in return for an equally remarkably small output of work. The success of the annual parties has rested largely on the willingness of member talent to be entertaining (and the dependable willingness of the guests to amuse themselves at the bar). At such times, there is little holding back. Why watch television, after all, or empty your pockets for a Broadway show, if you can have Willy and Olga Ley explain with words and gestures the structure of the Martian language – or watch your best friends cavort through a stefantic satire devised in the more mysterious byways of Fred Brown’s Other Mind – or listen yearly to a new and even funnier monologue delivered by Philip-William (Child’s Play) Klass-Tenn?

Between this yearly Big Events, club meetings very considerably in character. A member may arrive, on any given meeting date, to find a scant dozen seriously debating the date of publication of the second issue of Hugo Gernsback’s third magazine – or to find seventy-off slightly soused guests and members engaged in the most frantic of socializing, to the apparent exclusion of science fiction as a topic of interest. At these larger meetings, it takes a knowing eye to detect the quiet conversation in the corner where a new line of science fiction books has just been launched, or to understand that the clinking of glasses up front center indicates the formation of a new collaborating team.

Perhaps one of the most unlikely and most pleasant things about the Hydra Club is the way it manages to contain in amity a membership not only of writers and artists, but also of editors and publishers. We like to think that it is due to the “by invitation only” policy, and to the profound wisdom of our P.M.C., that the lions and the lambs have been induced to lie down so meekly all over the place. Even rival anthologists and agents are seen smiling at each other from time to time, and the senior editor of a large publishing house is always willing to pass on advice to newcomer specialist publishers. There are thirty-odd magazine writers in the crowd, and ten or more magazine editors – and still not a fistfight in a barload!

Hydra members are selected for interest, individuality, intelligence, and an inquiring mind, a combination unique among science-fiction organizations in my knowledge, we have now achieved four years of existence without a single major internal feud. What difficulties have arisen in relation to the club, from the outside, appear to be entirely due to the fact that, without trying, Hydra has become an increasingly important group in the professional field. But the business that takes place in and around the Hydra Club remains incidental.

When bigger and better purposes for clubs are found, the Hydra Club will still point happily to its nonexistent Article Two.

____________________

1 – Lois Miles Gillespie

2 – H. Beam Piper

3 – David A. Kyle

4 – Judith Merril Pohl

5 – Frederik Pohl

6 – Philip Klass

7 – Richard Wilson

8 – Isaac Asimov, Ph.D.

9 – James A. Williams

10 – Martin Greenberg (anthologist)

11 – Sam Merwin, Jr.

12 – Walter I. Bradbury

13 – Bruce Elliott

14 – J. Jerome Stanton

15 – Jerome Bixby (Twilight Zone!)

16 – Basil Davenport

17 – Robert W. Lowndes

18 – Olga Ley (Willy’s wife)

19 – Oswald Train

20 – Charles Dye

21 – Frank Belknap Long

22 – Damon Knight

23 – Thomas S. Gardner, Ph.D.

24 – Harry Harrison

25 – Sam Browne

26 – Groff Conklin

27 – Larry T. Shaw

28 – Lester del Rey

29 – Frederic Brown

30 – Margaret Bertrand

31 – Evelyn Harrison

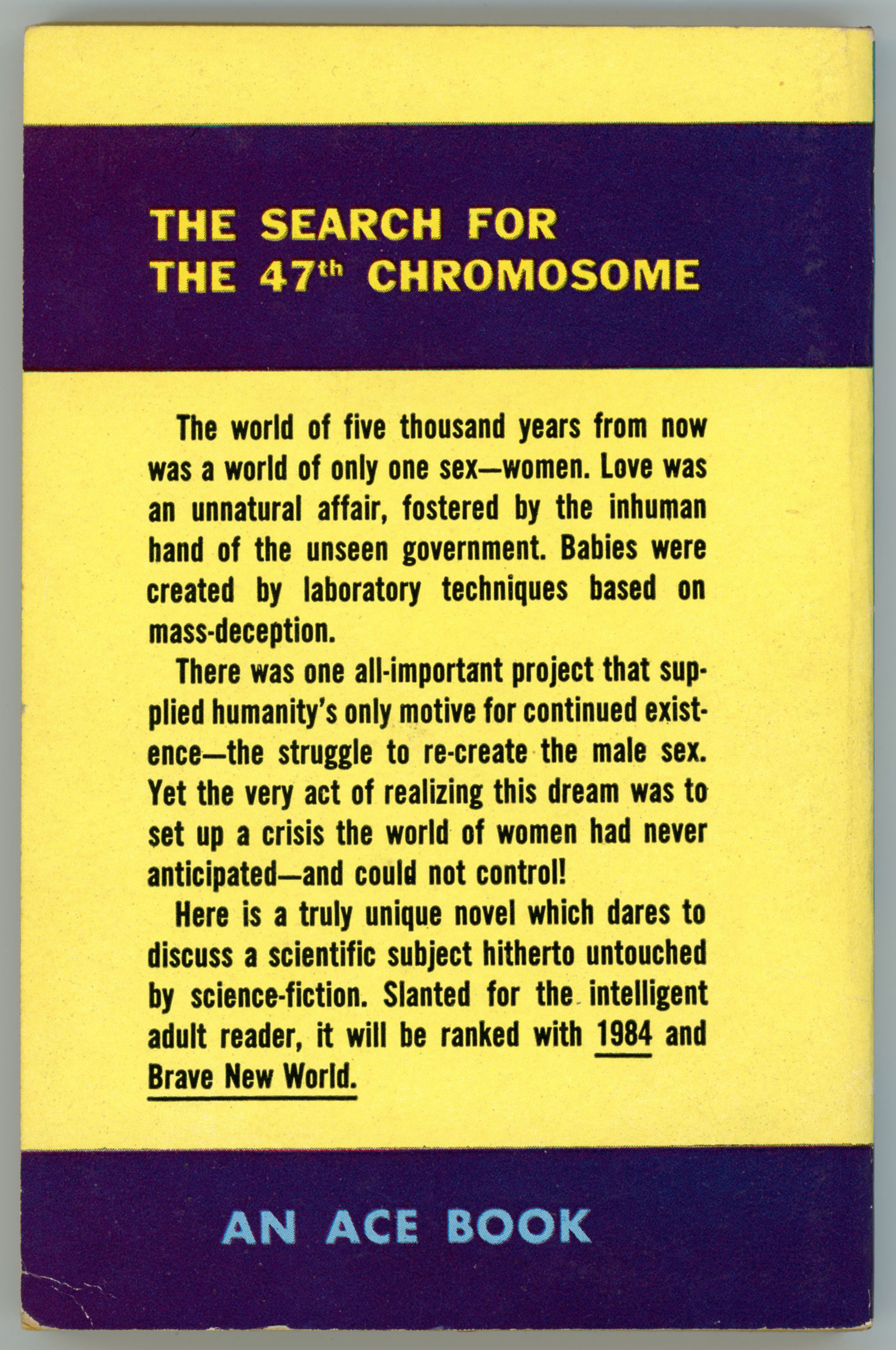

32 – L. Sprague de Camo

33 – Theodore Sturgeon

34 – George C. Smith

35 – Has Stefan Santessen

36 – Fletcher Pratt

37 – Willy Ley (Olga’s husband)

38 – Katherine MacLean Dye

39 – Daniel Keyes

40 – H.L. (Horace L.) Gold

41 – Walter Kublius

____________________

____________________

For your amusement…

Here’s the book where I found George Price’s cartoon…

Price, George (Introduced by Alistair Cooke), The World of George Price – A 55-Year Retrospective, Harper & Row, New York, N.Y., 1989

George Price, at…

… Art.com

Hydra Club, at…

… That’s My Skull (Judith Merril’s article, and, accompanying illustration)