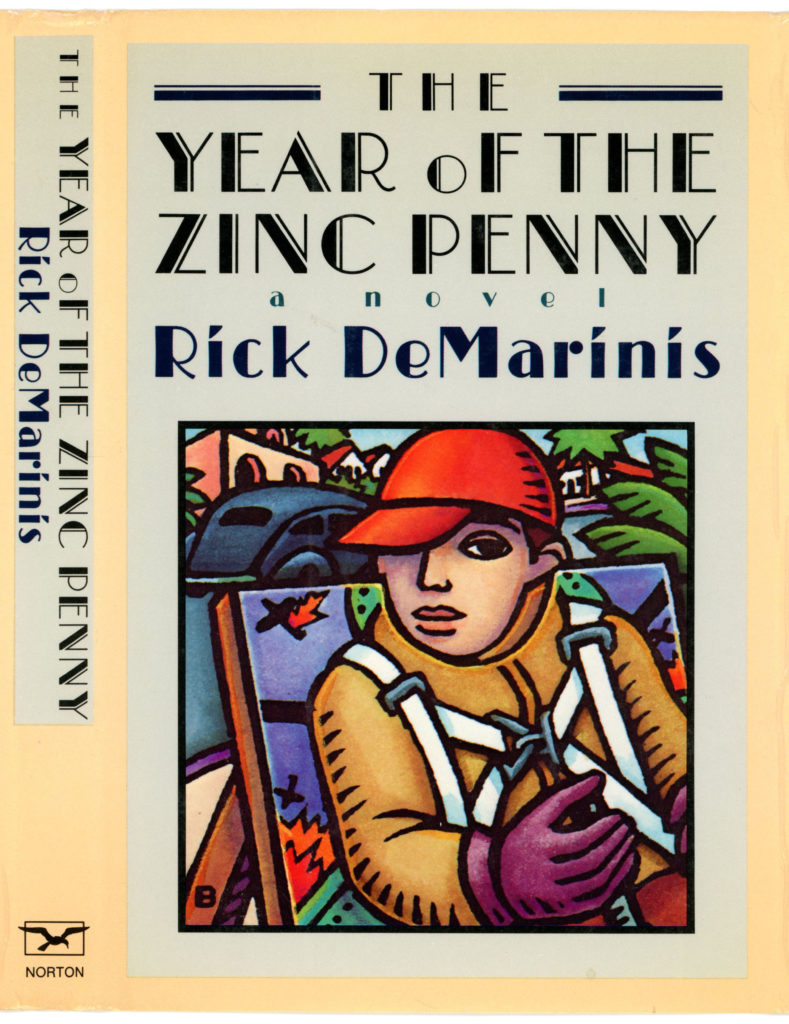

This post, which first appeared in mid-2018, has been updated to include Michiko Kakutani’s New York Times October 1989 book review of The Year of the Zinc Penny. The “initial” version of the post included the review as a scan, but this revision includes the review in full text, followed by a close-up of Anne Bascove’s cover art, which is as evocative as it is stylistically distinctive.

Scroll down, and enjoy…

She understood me, though.

She understood me, though.

Not my words but my acquiescence.

I relaxed back into the pillow and stared at the white ceiling.

She began to sing again as she dipped the washcloth into the pan of warm water.

“When the lights go on again, all over the world,”

she sang, her voice plaintive and sad.

Her melancholy tone made me think

that she had a boyfriend or husband overseas.

I imagined him an airman, a fighter pilot stationed in London.

He flew P-51 Mustangs and had shot down twelve Messerschmitt Me-109s

before getting shot down himself.

He was lying, helpless, in a hospital on the outskirts of London.

He couldn’t remember his name of where he came from,

and no one had told him just yet that his legs had been amputated.

He could remember his girlfriend or wife,

but only her pretty face and mournful singing voice,

not her name.

“Jenny,” he’d cry out in his delirium.

Then he’d sink back into his confused gloom.

“No, not Jenny,” he’d mumble.

(105)

I had discovered something about myself.

I knew that I was now capable of mustering any necessary lie at will.

I could say “Dad” and not mean it

and I could accept being called “son” by someone who did not mean it.

It was like discovering an unsuspected talent.

William and Betty didn’t have this talent,

and I was dimly aware that it was a deficiency that would cost them dearly.

I was also dimly aware that if this talent could be used without shame,

its power would be awesome.

And dangerous.

As dangerous as the one who used it as leukemia.

Because necessary lies trick the liar himself.

He wants to believe them.

Then he does.

“Stay clear of it,” Aunt Ginger had said.

Her words repeated themselves in my mind, gathering meaning.

(130-131)

____________________

Books of The Times

World War II Los Angeles, as a Boy Sees It

By MICHIKO KAKUTANI

The Year of the Zinc Penny

By Rick DeMarinis

174 pages. W.W. Norton & Company.

$17.95.

The New York Times

October 3, 1989

The year is 1943, when the war effort required that pennies be manufactured of zinc instead of precious copper; and Trygve Napoli, the narrator of Rick DeMarinis’s new novel, is 10 years old. His story of that year is, at once, a portrait of a vanished era, and an old-fashioned coming-of-age tale, showing one boy’s initiation into the solemnities of the adult world. If the novel’s material sometimes feels derivative – there are echoes throughout the narrative of the movies “Radio Days,” “Hope and Glory” and “Empire of the Sun” – Mr. DeMarinis’s voice remains distinctively his own, by turns comic and melancholy, lyrical and street smart.

Writing in brisk, observant prose, Mr. DeMarinis quickly immerses us in the staccato rhythms of life in wartime Los Angeles: rowdy sailors on leave, showing off their war wounds and tattoos; war widows working in aircraft factories, riveting wings and tails; children searching the skies above the city with their tin binoculars, on the lookout for enemy planes. A huge camouflage net spans one boulevard, covering the Douglas aircraft plant, and Tryg and his friends notice that it has been painted – surreally – to look like an ordinary farmland scene with houses, barns, and herds of dairy cows. The Japanese will never fall for it, says his friend William, noting that a Midwestern farm scene looks incongruously out of place in downtown Los Angeles. “The nut who designed it must have been from Iowa.”

When Tryg isn’t at the movies watching Ronald Colman, Claudette Colbert and Franchot Tone, he’s home listening to the radio, tuning in the Lone Ranger or whatever foreign station he can locate on his shortwave machine. With the help of his uncle, he builds a huge antenna on the top of his parents’ apartment building – an antenna that enables him to listen to the likes of Tokyo Rose, as he sits in the living room playing Parcheesi or concocting secret codes.

Tryg’s favorite pastime, however, is fantasizing about the war. Sometimes, he is an anonymous figure like Kilroy – someone who is everywhere and nowhere, partly hidden, in disguise. Other times, he is a brave fighter pilot named Charlie Jones or Bill Tucker, Jerry Granger or Buddy Thompson – someone without an awkward foreign name. He shoots down enemy pilots, dive-bombs strategic targets, and after his plane crashes, dies a heroic death in the arms of a beautiful girl.

“I loved the pose,” Tryg recalls. “I loved being someone everyone could like. To encourage this view of myself, I had to make it real. To make it real required a strong and unwavering imaginative act. I had to elaborate the details of my coming death in combat. This was important. I had to work at it. I couldn’t afford to be slack on the details.”

Though these fantasies earn Tryg a reputation as an oddball – “Monk, the Nut,” who’s constantly spacing out and mumbling to himself – they also provide a necessary respite from the boring rigors of school and the tensions of his squabbling family.

Tryg’s mother, who left his father for a smirking would-be actor named Mitchell, is a disturbingly cold woman, possessed of “a Norwegian fatalism.” When he was an infant, she abandoned him for four years, leaving him with her autocratic father; and now that she has retrieved him, she seems quite indifferent to his happiness or welfare. Mitchell, on his part, is a vain, selfish man, obsessed with parlaying his job as a Hollywood milkman into a movie career. He is completely cynical about the war – it doesn’t much matter, he says, which side ends up winning.

Filling out the Napoli household are Ginger, Tryg’s neurotic aunt, who acts like a California version of Blanche DuBois, and her violent husband, Gerald, who’s constantly getting into drunken brawls. Their son, William, a sullen, chain-smoking teen-ager, becomes Tryg’s mentor and surrogate brother. And William’s girlfriend, Betty, becomes a symbol to Tryg of the mysteries of sex that await him in adolescence.

Although these characters are all drawn in broad, colorful strokes, they never become generic cartoons, so deft is Mr. DeMarinis in portraying Tryg’s mixed feelings toward them of love and resentment, sympathy and irritation. In the course of the year, we watch him exchange needy loneliness for a more melancholy detachment, and we see him attempt to use the clear-sighted logic of childhood to solve the mysteries of love and death. By the end of the book, he is old beyond his years – initiated, by the war and assorted family tragedies, into the sadnesses of grown-up life.

“I had discovered something about myself,” Tryg says, recalling an exchange with his stepfather, who has just been drafted. “I knew that I was now capable of mustering any necessary lie at will. I could say ‘Dad’ and not mean it and I could accept being called ‘son’ by someone who did not mean it. It was like discovering an unsuspected talent.”

Without ever resorting to easy nostalgia or cheap sentimentality, Mr. DeMarinis gives us both a picture of the eternal realities of childhood – the humiliations of playground gamesmanship, the cruelties of puppy love – and a tactile portrait of life in the wartime 40s. In that sense, “The Year of the Zinc Penny” is like one of Proust’s madeleines: for those old enough to remember, it captures a receding past; for those too young to recall, it conjures up a vanished era.

____________________

– Rick DeMarinis –