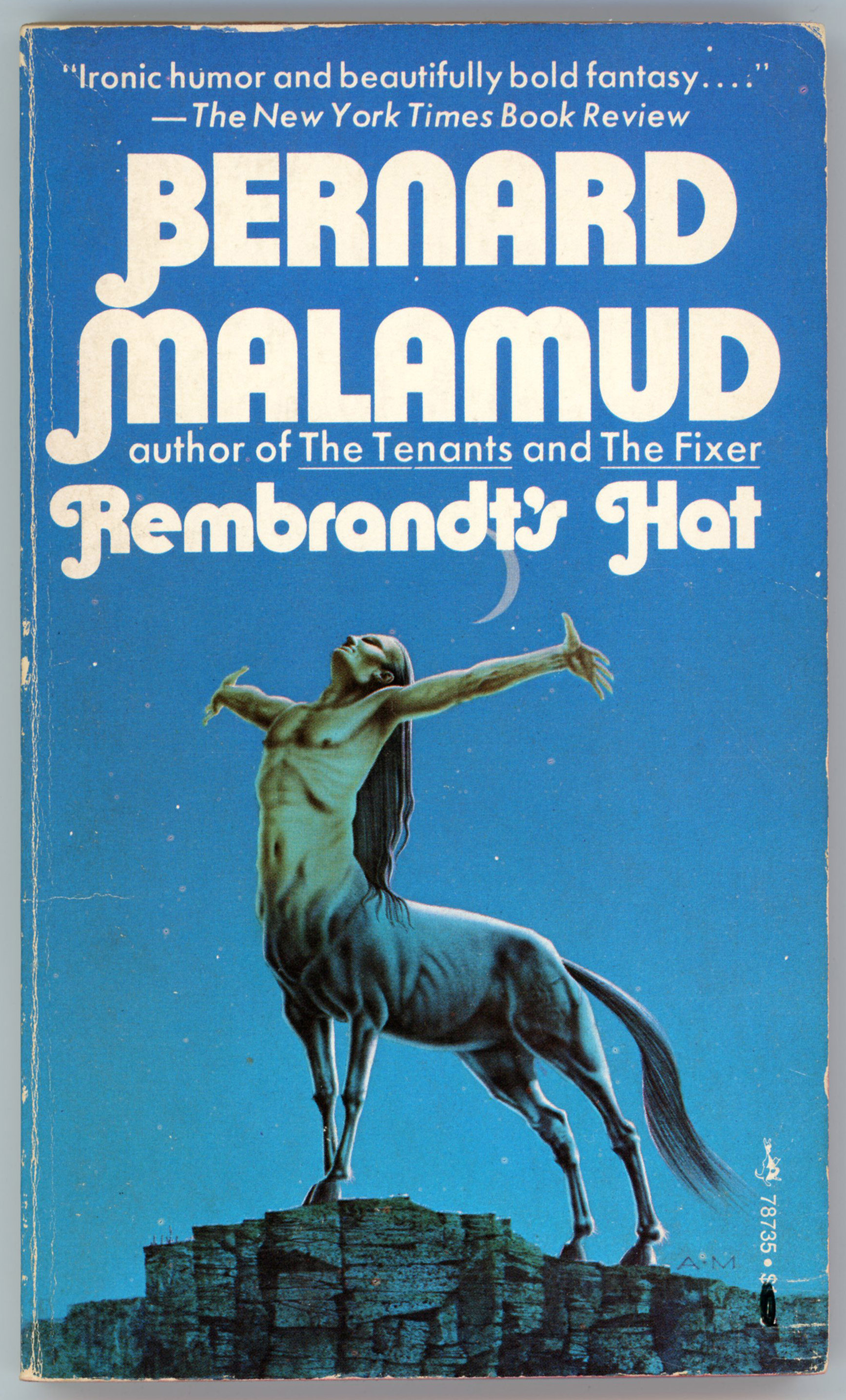

Dating from March of 2018, I’ve now updated this post to display the cover of a much better copy of Rembrandt’s Hat, than which originally appeared here. The “original” cover image can be viewed at the “bottom” of the post.

I’ve also – gadzooks, at last! – discovered the identity of the book’s previously-unknown-to-me-illustrator, whose initials, “A.M.” appear on the book’s cover. He’s Alan Magee, about whom you can read more here.

And, a chronological compilation of Bernard Malamud’s short stories can be found here.

Contents

The Silver Crown, from Playboy (December, 1972)

Man in the Drawer, from The Atlantic (April, 1968)

The Letter, from Esquire (August, 1972)

In Retirement, from The Atlantic (March, 1973)

Rembrandt’s Hat, from New Yorker (March 17, 1973)

Notes From a Lady At a Dinner Party, from Harper’s Magazine (February, 1973)

My Son the Murderer, from Esquire (November, 1968)

Talking Horse, from The Atlantic (August, 1972)

______________________________

Half a year later, on his thirty-sixth birthday,

Arkin, thinking of his lost cowboy hat

and heaving heard from the Fine Arts secretary that Rubin was home

sitting shiva for his recently deceased mother,

was drawn to the sculptor’s studio –

a jungle of stone and iron figures –

to search for the hat.

He found a discarded welder’s helmet but nothing he could call a cowboy hat.

Arkin spent hours in the large sky-lighted studio,

minutely inspecting the sculptor’s work in welded triangular iron pieces,

set amid broken stone sanctuary he had been collecting for years –

decorative garden figures placed charmingly among iron flowers seeking daylight.

Flowers were what Rubin was mostly into now,

on long stalk with small corollas,

on short stalks with petaled blooms.

Some of the flowers were mosaics of triangles.

Now both of them evaded the other;

but after a period of rarely meeting,

they began, ironically, Arkin thought, to encounter one another everywhere –

even in the streets of various neighborhoods,

especially near galleries on Madison, or Fifty-seventh, or in Soho;

or on entering or leaving movie houses,

and on occasion about to go into stores near the art school;

each of them hastily crossed the street to skirt the other;

twice ending up standing close by on the sidewalk.

In the art school both refused to serve together on committees.

One, if he entered the lavatory and saw the other,

stepped outside and remained a distance away till he had left.

Each hurried to be first into the basement cafeteria at lunch time

because when one followed the other in

and observed him standing on line at the counter,

or already eating at a table, alone or in the company of colleagues,

invariably he left and had his meal elsewhere.

Once, when they came together they hurriedly departed together.

After often losing out to Rabin,

who could get to the cafeteria easily from his studio,

Arkin began to eat sandwiches in his office.

Each had become a greater burden to the other, Arkin felt,

than he would have been if only one were doing the shunning.

Each was in the other’s mind to a degree and extent that bored him.

When they met unexpectedly in the building after turning a corner or opening a door,

or had come face-to-face on the stairs, one glanced at the other’s head to see what, if anything,

adorned it; then they hurried by, or away in opposite directions.

Arkin as a rule wore no hat unless he had a cold,

then he usually wore a black woolen knit hat all day;

and Rubin lately affected a railroad engineer’s cap.

The art historian felt a growth of repugnance for the other.

He hated Rubin for hating him and beheld hatred in Rubin’s eyes.

“It’s your doing,” he heard himself mutter to himself to the other.

“You brought me to this, it’s on your head.”

After hatred came coldness.

Each froze the other out of his life; or froze him in. (pp. 130-131)

March 25, 2018 255