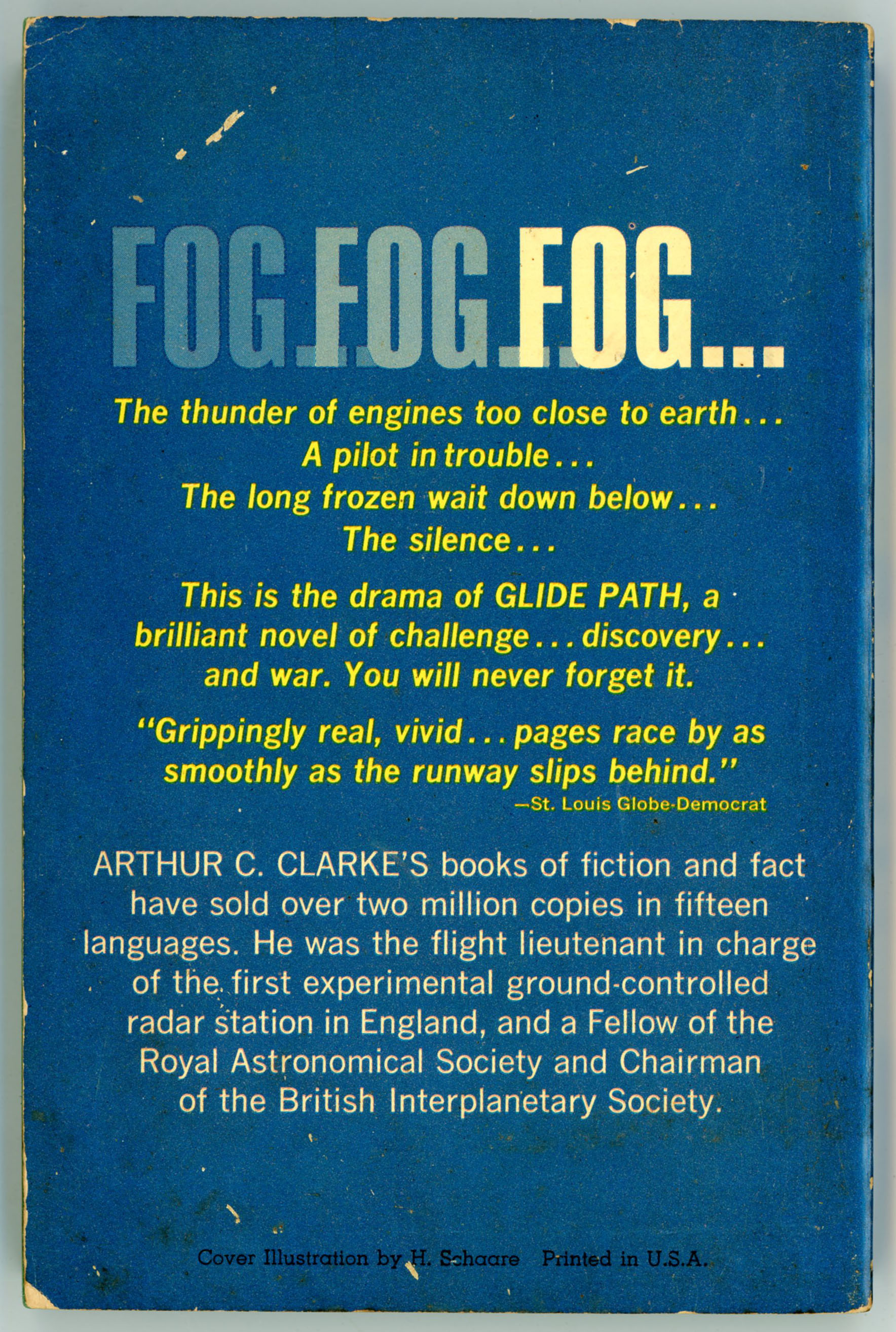

Tag: Harry Schaare

Glide Path, by Arthur C. Clarke – 1963 (1965) [Harry Schaare] [Revised post]

“It is strange how the mind can leapfrog across the years,

selecting from a million, million memories for one that is even faintly relevant,

while rejecting all the others.”

C Charlies was like a fly crawling over this darkened clock face.

C Charlies was like a fly crawling over this darkened clock face.

It had been aimed at the narrow illuminated section,

but might already have missed it,

to remain lost in the blackness that covered almost all the dial.

So this, Alan told himself without really believing it,

was probably the most dangerous moment of his life.

Introspection was not normally one of his vices;

he could worry with the best,

but did not waste time watching himself worrying.

Yet now, as he roared across the night sky toward an unknown destiny,

he found himself facing that bleak and ultimate question which so few men can answer to their satisfaction.

What have I done with my life, he asked himself,

that the world will be the poorer if I leave it now?

He had no sooner framed the thought than he rejected it as unfair.

At twenty-three, no-one could be expected to have made a mark on the world,

or even to have decided what sort of mark he wished to make.

Very well, the question could be reframed in more specific terms:

How many people will be really sorry if I’m killed now?

There was no evading this.

It struck too close to home,

brought back too vivid a memory of the tearless gathering around his father’s grave.

______________________________

It is strange how the mind can leapfrog across the years,

selecting from a million,

million memories for one that is even faintly relevant,

while rejecting all the others.

Elusive Horizons, by Keith C. Schuyler – 1969 [Harry Schaare] (Revised content – June, 2018)

The author: Keith C. Schuyler, Sr. at his typewriter, in an image (UPL 6809) from the American Air Museum in Britain. Though undated, given the design of the telephone and manual (!) typewriter, and pack of Camel cigarettes (how refreshingly politically incorrect!) the picture presumably dates from the 1940s. Perhaps Mr. Schuyler is seen typing the very manuscript which is the feature of this blog post?

Keith Schuyler, Sr., born in 1919, passed away at the age of 89 in November of 2008, and is buried – alongside his wife, Eloise Jean (Helt) Schuyler – at the Elan Memorial Cemetery in the east-central Pennsylvania town of Lime Ridge, his simple and unadorned tombstone belying the profundity of his wartime experiences. Mrs. Schuyler’s biography – she had a very busy and full life – can be found here.

______________________________

We hadn’t had a piece of flak.

I was straining to keep from peeling away from my element.

The mission was over.

Still we continued in a straight line,

the same heading on which we had bombed. Then it came.

At first the flak was off to our left,

big black mushrooms that indicated at least 128-mm guns.

At the first bust, our lead ship finally began his bank to the right.

But it was too late.

By the time the movement had been relayed to me

and I whipped along behind the spear of bombers,

the ground gunners had us bracketed.

The big bursts were right among us.

And, they followed us even as we crossed the coast.

Then we were almost out if it.

Maybe it was a desperation try,

because the flak was drifting toward the rear of the formation.

Maybe it was the last volley of four. But – it was there!

Even as I watched the element lead directly ahead of me,

instinctively holding close formation although our bombs were long gone,

minutes behind us, it happened!

He caught a direct hit just starboard of the number three engine.

The wing flipped up as though on a hinge,

and the hinge was a bolt of orange-red flame and black smoke.

The extra lift of the good wing threw the bomber into a right snap roll

before the pilot had a chance to catch it.

And from the moving picture screen of my windshield,

the Liberator twisted down out of sight.

Instinctively I ducked aside as debris from the doomed one

crashed into my center windshield and shattered the bulletproof glass.

“He’s spinning, still spinning,”

I heard as from a distance over my interphones.

The airplane was as good as dead, and now it had no personality.

My crewman spoke of her pilot. Now it was “he” spinning.

And he was a crew of ten men whirling

like the burning winglet of a maple seed.

Human flesh was being smashed by centrifugal force

against the metal guts of the dying one

as her crew tried to scramble for the exits.

Then came the inevitable “There she goes; blew all to hell!”

Use of “she” exonerated the pilot of any part in this sordid happening

as again, in this desperate instant when she gave up in a ball of flame,

the Liberator had her last identity.

We were well out over the water when it happened,

and any who got out would … my thoughts were cut off by the interphone:

“No chutes.”

Ahead, the wingmen of the fallen bomber held their positions.

There was only a piece of empty sky ahead of and between them

where moments before the leader of their element

had marked trail for us. I couldn’t stand that empty sky,

and I forced the reluctant Wasp Nest into the blank hole.

Still the question burned into my brain, “Why didn’t he turn?”

It came out later that the lead ship

wanted to get good pictures of the bomb drop.

I hope the pictures were good.

The kid who went down was on his 24th.

**********

From Missing Air Crew Report 4257: “Aircraft No. 467 was observed to receive a direct hit by flak between #3 and #4 engines. The right wing fell off and the aircraft tipped on its left wing and started down in a tight spiral. It became enveloped in flames and exploded. No parachutes were seen.”

**********

From 44th Bomb Group Roll of Honour and Casualties:

Date: 27 April 1944

Target: Moyenneville, France

Squadron: 67th Bomb Squadron

Aircraft: B-24J Liberator 41-29467

This day was the first of the double-header days for the Group, with two separate missions being flown. One plane was lost on the first mission due to the moderate to intense, accurate flak, which hit Lt. Clarey’s aircraft.

Crew

Pilot: CLAREY, HOWARD A. Jr., lst Lt.; Yardley, PA – KIA

Co-Pilot: RHODES, CARL E., 1st Lt.; Birmingham, AL – KIA

Navigator: FORREST, GEORGE W., 2nd Lt.; Upper Darby, PA – KIA

Bombardier: HINKLE, GLENN E., 2nd Lt.; Burlingame, CA – KIA

Flight Engineer: SHIRLEY, RAYMOND, S/Sgt.; Lexington, KY – Prisoner of War

Radio Operator: CHAGNON, PAUL L., S/Sgt.; Salem, MA – Prisoner of War

Gunner (Nose Turret) LYTLE, LESLIE L., Sgt.; Portland, OR – KIA

Gunner (Right Waist) RIEGER, MARTIN A., S/Sgt.; New York, NY – KIA

Gunner (Left Waist) PHILLIPS, ALLEN W., S/Sgt.; Richmond Hill, NY – KIA

Gunner (Tail Turret) YOUSE, CHARLES M., Sgt.; Sunbury, PA – KIA

Radio operator Paul Chagnon was the first man to escape from the falling aircraft, followed by the engineer, Sgt. Raymond Shirley. The pilot, Lt. Howard A. Clarey, Jr. also managed to free himself from the doomed ship but his parachute did not open, or did not have time to open. It could have been that he was knocked out by the explosion and never regained consciousness, but the two men who survived to become POWs did not know for sure.

This was Lt. Clarey’s 28th mission, having flown all previous missions as a co-pilot for Lt. McCormick. This was his first mission with a new crew, which was on its fifth mission.

In a letter dated December 4, 1992, Ray Shirley wrote: “At briefing that morning we had been told that there was one battery of four guns at the target. We were on the bomb run. Paul Chagnon, radio operator, was on the catwalk holding the bomb bay doors open, I was in the top turret. Immediately after dropping our bombs, we took a direct hit just outboard of #3 engine and lost the wing from there out. I saw it start spinning like a seed pod falling from a tree in the fall season.

“I was thrown forward in the turret as the aircraft started spinning to the right and I started coming out of the turret during which I saw Chagnon bailing out from the catwalk with my chest chute. Someone pulled the plane out briefly and then we started spinning again to the left. I managed to get Chagnon’s chute from his position, got it on and went to the catwalk to bail out.

When I bailed out, Lt. Clarey was on the catwalk to bail out when I left the ship. I finally found the ripcord and started my descent slipping the chute on the way down and ending up with a badly sprained right ankle upon landing. I took up bowling after the war to strengthen it up.

“After getting to the ground, Chagnon came to help me and French civilians were trying to help us. They carried our chutes off and, of course, were speaking French. Chagnon had been born in Canada and had been brought up on French until they moved to the U.S. when he was six or seven years old. But that day he didn’t remember one word of French so the civilian efforts were of no avail. Anyway, Chagnon was helping me. Then the French abandoned us as the German military began to arrive at the scene.

“Chagnon and I approached a barn, which we hoped to get into and hide. As we rounded one corner of the barn, the Germans came around the barn corner at the opposite end with their little ‘burp guns’ and that was it. They put us into a small truck, the bed portion had a cover on it, and inside the truck was Lt. Clarey’s body. His chute had failed to open. We saw no other bodies other than that of Lt. Clarey.

“The Germans took us to a building with an underground bunker where we stayed one or two nights, then through Paris to Dulag Luft and from there to Stalag Luft VI via the 40 or eight rail cars. We were subsequently evacuated from Luft VI to Luft IV via that damned freighter down the Baltic. From IV, I was shipped to Luft I, again on a 40 or eight-rail car and Chagnon wound up on one of those forced marches as the Germans fled from the approaching Russians. The Germans abandoned us at Luft I just a few hours before the Russians arrived. We were eventually evacuated to Camp Lucky Strike in France.”

Photograph of crew from 1992 hardcover edition of Elusive Horizons

Photograph of crew from 1992 hardcover edition of Elusive Horizons

**********

“…over Holland or very close to it,” Rauscher had said.

The long-defeated Dutch were still our allies.

A B-24 Liberator could cause a lot of damage when it hit.

I started a 180-degree turn. Let her blow in Germany!

I took a quick glance back through the fuselage. It was empty.

It was the emptiest airplane I had ever seen!

In that brief second, I felt as lonely as I had ever felt in my life.

I flicked on the aileron switch of the automatic pilot,

always set for emergency.

As I rose hurriedly from my seat, I felt something grabbing at my waist.

It was the cord to my heated suit.

Carefully I reached back and unplugged it so that the cord wouldn’t break.

Then I was on the catwalk of the bomb bays, sat down,

to roll out, forward into the clouds.

The wind swept my legs back.

I gathered my feet under me on the catwalk

and dived headfirst through the opening.

As I tumbled below and away from our airplane,

I had the sensation we once had as kids

when we would dive under a high waterfall to get to the recess behind it.

Then I extended my arms, as I had been taught,

to get into correct forward position before opening my chute.

I was in no immediate hurry.

I had told the crew to delay their chute for a number of reasons.

The Kraut was still hunting for us,

and he might foul a chute accidentally in the clouds.

Or, as some had been in the habit of doing,

he might gun the men in their chutes.

The less time we hung in the sky,

the less time the Germans would have to get to our landing site.

And we could spare a moment or two to slow down

to the terminal velocity of a falling human body

of about 120 miles per hour.

I almost waited too long.

When in good position,

I grabbed the ring on the harness of my back pack,

pulled, and felt the snap.

I braced for the shock, but nothing happened.

I looked at my harness.

The cable was still trailing from its sheath!

When I pulled again, the cable came free. I clung to the ring.

Somewhere I had heard that a good jumper does not lose his ring.

I wondered why I couldn’t see or hear our airplane.

Years later,

Renfro said he said it blow all to hell as he was coming down in his chute.

The 190 did come in on Schow. Hanging helpless, Schow just waved.

The German waved back. He had his kill – chalk up one more B-24.

Strung out behind me were the other parachutes,

some still higher than mine.

I reached for my leg straps,

to free them so that I could take off when I hit.

But the ground was coming at me.

I braced with bent knees, hit, and somersaulted in approved fashion.

Military chutes let you down hard. But I was okay.

Quickly I gathered my parachute

and tried to hit it from possible spotting planes.

Of to my left about a hundred yards was a farmhouse,

and when the German woman on the porch saw me look her way,

she went inside.

The sun was now shining brightly. It was about 1 P.M.

I squinted toward the western horizon.

There were bombers still in view sailing serenely into the west. B-17s.

For an instant, I felt lonely. I thought of home.

They would worry when they got the word.

Then I suddenly realized that I was alive and well.

I felt ridiculously happy.

Like the night I ran down the hospital steps

away from all that I loved most,

I felt a serenity completely at odds with my situation.

I had crossed another horizon.

Photograph of crew from 1992 hardcover edition of Elusive Horizons

Photograph of crew from 1992 hardcover edition of Elusive Horizons

**********

From Missing Air Crew Report 4464: At 14:00 hours A/C 279 (“I”) was observed straggling, low and to the right of the formation in the vicinity of 52 40 N, 05 18 E. #2 engine was feathered but apparently under control.

**********

From 44th Bomb Group Roll of Honour and Casualties:

Date: April 29, 1944

Target: Berlin, Germany

Squadron: 67th Bomb Squadron

Aircraft: B-24H Liberator 42-100279, “Tuffy“

Specific target was the underground railway in the heart of Berlin. Our formation of 21 aircraft encountered moderate to intense flak and from 30 to 50 enemy aircraft sustaining their attacks from Berlin back to Holland, most of this time unescorted. Three of our aircraft did not return.

Crew (All survived as Prisoners of War)

Pilot: SCHUYLER, KEITH C., 2nd Lt.; Berwick, PA

Co-Pilot: EMERSON, JOHN F., 2nd Lt.; Santa Monica, CA

Navigator: RAUSCHER, DALE E., 2nd Lt.; Goodland, KS

Bombardier: DAVIS, JAY LARRY, 2nd Lt.; Cleveland, OH

Flight Engineer: SANDERS, WILLIAM L., S/Sgt.; Karnak, IL

Radio Operator: ROWLAND, LEONARD A., S/Sgt.; Portland, OR

Gunner (Ball Turret) REICHERT, WALTER E., Sgt.; Farragut, ID

Gunner (Right Waist) COX, GEORGE G., Sgt.; Louisa, KY

Gunner (Left Waist) RENFRO, GEORGE N., Sgt.; Handley, TX

Gunner (Tail Turret) SCHOW, HARRY J., Sgt.; Austin, MN

2nd Lt. Schuyler was the pilot of TUFFY. His navigator, Dale E. Rauscher relates his experiences, “Our aircraft was under control as we dropped behind the formation. We had been badly damaged by flak and we were unable to keep up with the formation. We were doing okay until about ten or twelve FW 190s spotted us and came in at us head-on. Their first pass hit us pretty badly, although no one was killed or wounded.

“There was cloud cover at about 5,000 feet, so Schuyler put the nose down and we headed for the clouds. I think only one enemy aircraft followed us, and he kept coming in on us each time we came out of cloud cover. We had iced up and had to come out of the clouds to try to get rid of a little ice buildup. We played hide and seek in the clouds for awhile, but finally ran out of clouds.

“Our gun stations were out of ammunition, fuel tanks had been hit and we had two fires in the tail section, so we were told to bail out. We had about fifteen minutes of fuel left when we finally abandoned ship. As we had been flying all over the sky and in every direction while trying to shake off those fighters, I was not positive where we were, but we were about forty or fifty miles east of the Zuider Zee. We bailed out safely and were all captured a short time later.”

The plane crashed at 1400 hours, 10 miles east of Holland at Tilloy – Floriville, County of Meppen.

Lt. Keith C. Schuyler, pilot, has written a book of his wartime experiences titled “Elusive Horizons” and gave permission to include some of his account of that day. “Berlin was always a rough one. This was a symbol of Germany’s might. There were still plenty of German fliers willing to die for Berlin for ideological reasons. There were plenty more who had lost their grasp on symbols but flew and fought us in exquisite machines that were manufactured out of the best parts available.

“We were told that we could expect heavy fighter opposition. The Luftwaffe had been unusually quiet for the past week, and we expected plenty of trouble today. ‘You will have fighter cover much of the way, but you know they can’t stick around long,’ we were told.

“Some fighters were overhead, friendly fellows cutting contrails back and forth in a protective web that made you feel good. Then Larry Davis, bombardier, cut in on the interphone, ‘Fighters! A whole swarm of them!’ I didn’t see them at once. Larry pinpointed them, “Straight ahead, low at twelve o’clock!’

“Then I saw them … and took a deep breath. Coming up at us like a swarm of bees was a literal swarm of at least forty German fighters. And they were headed directly at our formation! Like specks at first, in almost an instant they materialized into wings and engines.

“Then there was a hellish roar as everything became a confusion of sound and motion. Like entering a tunnel with the windows open on a train – dust, noise, and debris became indistinguishable. Right over my windshield a German fighter came apart in a glimpse of flame and junk. That was Larry’s.

“A B-24 that had been lagging at seven o’clock, drew in close at five o’clock just as a German came through. The fighter smashed head on into the big one right at the nose turret and both planes exploded in a ball of flame. Then it was over. For us.

“Somehow, after you have dropped your bombs, you get the feeling that everything is all right. If your airplane is working as it should, it becomes more a matter of whether you have enough fuel for the trip back. At least that is the feeling you have. But deep down inside you know it is not over. This is not a game. They want to punish you for what you did if they can. So they try.

“Somehow our lead plane took us over Brandenburg on the way out, so the Germans would now get another crack at us with their flak guns. Although it was heavy, we seemed to be getting by without incident. Then I noticed four bursts off our left wing, maybe a hundred yards out, and just below our level. Then four more, closer. Fascinated, I watched as four more burst just ahead of and below our left wing, possibly 30 yards away. I didn’t see the next bursts – but I heard them. And our ship shook to the concussions. Immediately, #2 prop ran away. The torque, as the propeller screamed up to over 3,000 rpm, dragged at our wing, and I leaned into the rudder, then hit the feathering button. We were hurt again – badly.

“A hole in #2 cowling gave visual evidence that we had caught plenty from the last volley of flak, the manifold pressure on #4 was down badly. The supercharger had probably been knocked out. Although the engine was running smoothly, it would not do much more that carry its own weight at over 20,000 feet.

“Normally, we wouldn’t have too much to worry about, but we were still a long way from home. The disruption in power had dropped us back behind the formation and there was no chance of catching up. I personally called the lead ship. ‘Red leader, we’ve got some problems back here. Can you slow down a little?’

‘We’ll try,’ the answer came back, ‘but we can’t cut it back much.’

“But it soon became evident that we couldn’t keep up. We kept dropping back – slowly, inexorably … If we were hit in the wings as much as I feared, there was a good chance that we would be losing fuel from the wing tanks. I called Sanders, our engineer, who climbed down out of his turret to check the gas supply. His report confirmed my suspicions. There was a serious imbalance in the gasoline tanks to indicate that we were losing some somewhere. I asked Rauscher, navigator, for our estimated time of arrival in England and his fast mental calculations convinced me that we were not going to make it home. We’d be lucky to stretch our glide to make the North Sea. But I kept this news away from the crew.

“Again it was Larry who alerted us to fighters, ‘Off to the left. They are hitting the group off to the left.’ There were eight of them! And had they elected to come at us singly, subsequent events might have been different. But they came straight on, strung out wing to wing, like a shallow string of beads. FW 190 they were! And I had only an instant to make a decision of how to deal with them.

“Get ready, I called. I, too, got ready. I didn’t make my move until I saw the leading edges of the FW’s start to smoke and yellow balls begin to pop around out wings. Then I dove straight for the middle of the string of beads! Either they would get out of the way or we would take a couple of them with us. They scattered!

“Deliberately, I held the nose of the bomber as straight down as I could manage. But she was trimmed for level flight and wanted to come out of the dive. Jack Emerson saw my quivering arms and added his strength to keep the nose down. I wanted those fighters to think they had us. The strategy worked on five out of the six remaining, but that one was destined to give us more trouble than all of the others combined. He did not believe us.

“I heard Jack shout under his oxygen mask and I felt the controls wrenched from me for an instant. Jack had seen him coming from his side and he rolled the bomber into the attack. Tracers cut by the left side of the fuselage as the tortured Lib responded. We kept the pressure on the elevators and the nose toward the ground as I watched the air speed pass the red line. Then it touched 290, which gave us somewhere around 400 mph at our altitude. Below us I could see a solid cloud cover and it was our only refuge. But in one of the frequent paradoxes of war, to gain them was also our undoing. Our precious altitude, needed to get us somewhere near home, was being used up in a desperate effort to escape the more obvious danger from the fighters.”

The cat and mouse drama continued for a considerable time, including the added problem of icing, and then the clouds ran out. The tail gunner, Schow, later told Lt. Schuyler, “The fighter came in at 5 o’clock. I started firing but the tracers bounced right off him. And then, when I was just pressing triggers, nothing was happening. It was only an instant before I could find the extent of damage. A 20 mm had hit us in the right elevator. It blew my hydraulic unit onto the floor, clipped off my left gun, cut my mike cord about an inch and a half from my throat, and generally took my plexiglass.

“I tried to fire my right gun manually, but it, too, was ruined. So I got out of the turret, went to the waist, where another fire had started, put on my chute and told Sgt. Cox to relay the news to the pilot, but Cox had already done that.” Both men then attempted to extinguish the two fires, waist and turret.

“With only 50 gallons of fuel left, two fires and only one gun left firing, the time had come. We were close to being over Holland – possibly 40 miles away from the Zuider Zee. “I started a 180- degree turn. Let her blow in Germany! A quick glance back through the fuselage – it was empty. Flicked on the aileron switch of the automatic pilot, always set for emergency, rose hurriedly from my seat; then onto the catwalk in the bomb bay.

“As I tumbled below and away from our airplane, I was determined to delay the opening of my parachute. And I almost waited too long! Later, I was told our ship blew all to hell.” All ten men survived to become POWs.

References

Missing Air Crew Report 4257

Missing Air Crew Report 4464